Child labour remains a pervasive issue that plagues countries worldwide, particularly in developing nations. Defined by the

International Labour Organisation (ILO) as work that is mentally, physically, socially, or morally detrimental to children, child labour disrupts their education by either denying them the opportunity to attend school, forcing premature departure from education, or burdening them with excessive work alongside schooling. In its most extreme manifestations, child labour involves enslavement, separation from families, exposure to hazardous conditions and illnesses, and abandonment.

This article explores the present incidence of child labour and its impact on the long-term prospects for youth development and economic growth for the Global South. Focusing on the economic implications of children in employment on a country’s ability to leverage upon its demographic window of opportunity (DWO), it places the eradication of child labour as a cornerstone for achieving sustainable economic growth in the Global South’s development agenda.

Where does the Global South stand today?

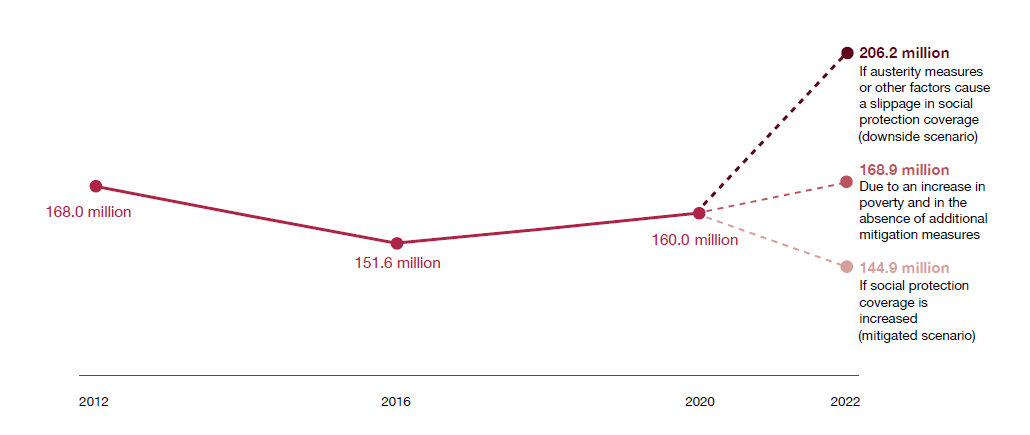

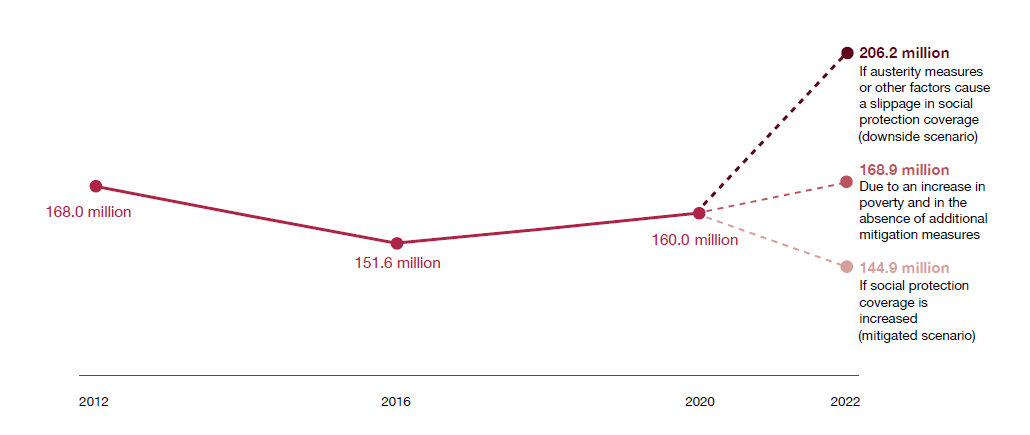

Since 2000, the global progress towards eliminating child labour (in all its forms) witnessed a commendable rise. From over

245.5 million (16 percent) of children aged between 5-17 years employed in non-hazardous or hazardous work in 2000, child labour declined to

151.6 million (9.6 percent). However, between 2016 and 2020, there has been no significant movement—the rate of child labour remained at

9.6 percent, with an additional 9 million children in employment (in absolute terms). Among them,

79 million faced hazardous conditions, jeopardising their well-being and overall development. While official estimates are unavailable,

the ILO report on Child Labour: Global Estimates 2020, Trends and the Road Forward projects that the COVID-19 pandemic has likely pushed another 8.9 million children into vulnerable employment without concerted efforts to tackle such outcomes.

Figure 1: ILO Projections for Global Incidence of Child Labour in 2022

Source: Child Labour: Global Estimates 2020, Trends and the Road Forward

Source: Child Labour: Global Estimates 2020, Trends and the Road Forward

These numbers, however, mask significant regional disparities. Sub-Saharan Africa exhibits the highest prevalence of child labour at

24 percent. This is three times higher than Northern Africa and Western Asia, four times higher than South and Southeast Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean, and 10 times as high as Europe and North America. Concerns regarding the Global South’s progress in eliminating child labour have escalated, with the region witnessing an uptick in the share of children in employment between 2016 and 2020, while the incidence of child labour continued to decline (although at a slower rate) in the advanced economies. Moreover, the share of children in employment or unpaid forms of child labour is noticeably

higher in the agriculture sector, informal labour in family units and unpaid domestic or care work. Considering these sectors occupy a more prominent share in the Global South economies, children in these countries remain more vulnerable to child labour employment.

A vicious cycle: Child labour and economic growth

Although recognised as detrimental to society, child labour persists due to

various factors incentivising households and firms to engage in this practice. Poverty, income constraints, limited access to education, and low expected returns drive impoverished households to send their children to work. Vulnerability to risks and credit market imperfections also contribute to the prevalence of child labour. Additionally, firms which seek to maximise profits employ child labour for longer working hours at lower wages, leading to overall

cost advantages. In regions like Sub-Saharan Africa or South and Southeast Asia, the exploitation of children artificially reduces labour costs, creating an unfair comparative advantage in global markets and attracting foreign investments to these sectors. This often incentivises firms to exploit child labour for short-term consignment work outside the formal safety nets of the economy.

Concerns regarding the Global South’s progress in eliminating child labour have escalated, with the region witnessing an uptick in the share of children in employment between 2016 and 2020, while the incidence of child labour continued to decline (although at a slower rate) in the advanced economies.

However, the problem runs

both ways—a higher incidence of child labour directly impedes economic growth in the medium and long run. By suppressing market wages for unskilled labour and discouraging diversification into skill-intensive technologies, child labour leads to low current income levels. Moreover, child labour perpetuates the cycle of poverty, particularly in rural households. It can be a significant factor contributing to low levels of long-term economic growth in the Global South. It often deprives children of their early-stage learning opportunities and skill acquisition, limiting their economic productivity and employment opportunities in the long run.

Vulnerable to employment as child labour, children in the Global South are more likely to lack necessary productive skills and, therefore, potentially earn low wages in the future. For more than

one-third of children in child labour worldwide, the struggle to balance the demands of school education and work life remains a concern. If not forced to drop out of school, these children often struggle to catch up to their peers in terms of learning outcomes and hence career progression. While Europe and North America have a significantly low incidence of child labour out of school, the corresponding

numbers are much higher for East and Southeast Asia (37.2 percent), Central and South Asia (35.3 percent), and Africa (28.1 percent).

Vulnerable to employment as child labour, children in the Global South are more likely to lack necessary productive skills and, therefore, potentially earn low wages in the future.

The incidence of child labour also hinders the acquisition of technological capabilities and transition to higher education, impeding the prospects for sustainable economic growth. Child labour also leads to physical injuries, sexual exploitation, emotional mistreatment, and neglect, hindering human capital development for the countries’ youth population and long-term health issues, such as respiratory diseases and cancers, further impacting the population’s economic and social well-being.

These imply severe economic consequences for the Global South, as a significant share of its relatively younger population remains vulnerable to exploitation. Hindering youth development through the early stages of childhood, child labour bears direct implications for the Global South economies’ potential to take advantage of their

demographic window of opportunity. Featuring a low support ratio, populations with a broader and highly productive working-age population can boost economic growth significantly. Therefore, this phase of demographic transition is identified as a ‘window of opportunity’.

Most countries in Asia, Latin America, and the Caribbean have entered their respective windows, while most African countries are still in the pre-window phase. This allows developing economies to harness their demographic dividend to deliver sustainable economic growth. However,

previous research indicates that a county’s potential to leverage this demographic dividend for economic growth depends on more fundamental factors such as human and physical capital levels, labour market structure, and financial architecture. Child labour contributes to low levels of human capital formation, hindering youth development and, therefore, the productive capacity of the working-age population in the Global South.

Hindering youth development through the early stages of childhood, child labour bears direct implications for the Global South economies’ potential to take advantage of their demographic window of opportunity.

Therefore, as the developing and least developed countries (LDCs) prepare to take advantage of their favourable demographic transitions over the coming decades, it becomes crucial for them to address the issue of children in employment and prioritise progress along SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth. Mainly, Target 8.7 under SDG 8 aims to “take immediate and effective measures to eradicate…the worst forms of child labour…and by 2025 end child labour in all its forms”. To achieve this, a wide range of policy instruments need to be advanced. Social protection stimulus through direct benefit transfers or access to credit and insurance can reduce child labour supply by directly augmenting household income. Integration into the global economy can be leveraged to minimise child labour through development assistance programs or partnerships such as

Alliance 8.7 that generate scalable investments in public education and health, lend a knowledge-sharing platform to identify best practices and create opportunities for engagement among all relevant stakeholders to ensure progress. Abstracting from specific instruments, most importantly, a comprehensive strategy for combating child labour in the Global South must focus on preventing, withdrawing and rehabilitating children in employment. By adopting this three-pronged approach, countries in the Global South can make significant progress in addressing the pervasive issue of child labour and enabling sustainable economic growth.

Debosmita Sarkar is a Junior Fellow with the Centre for New Economic Diplomacy at the Observer Research Foundation

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Child labour remains a pervasive issue that plagues countries worldwide, particularly in developing nations. Defined by the

Child labour remains a pervasive issue that plagues countries worldwide, particularly in developing nations. Defined by the

PREV

PREV