-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

COP28 offered something to every stakeholder but not enough for the world

Former Vice President of the United States (US) and co-recipient of the 2007 Nobel Peace Prize (with the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [IPCC]), Al Gore, commented that appointing the chief of one of the largest and, in Al Gore’s words “least responsible companies” as the President of the 28th meeting of the Conference of Parties (COP28) was an abuse of public trust. Sultan Al-Jaber, President of COP 28, also serves as the head of the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (ADNOC) and has declared that the United Arab Emirates (UAE) would double oil and gas output this decade. Media reports indicate that over a hundred US lawmakers and members of the European Union parliament had called for his removal. According to the Guardian, at least 166 climate “deniers” and fossil fuel lobbyists attended COP28. Former United Nations (UN) Climate Chief Christiana Figueres said the COP28 presidency had been “caught red-handed” and “will be under public scrutiny like no other ever before” in response to the news that the UAE planned to strike secret oil and gas deals behind the scenes at COP28. Does all this mean that COP28 was robbed by the oil and gas industry and lobbies that support them?

The initial substantive decision on loss and damage fund and funding arrangements, on the first day of the conference with funding commitments of over US$700 million, was well received by most stakeholders except for those who knew that opening a bank account means little if it does not receive the funds promised. The promised sum is only about 0.1 percent of the US$400 billion that is needed. Another issue of concern is that the World Bank will administer the fund for a negotiated fee of 24 percent which means that one in four dollars pledged will never make it to the countries in need. Six countries pledged new funding to the Green Climate Fund (GCF) with total pledges of US$12.8 billion from 31 countries. These financial pledges are far short of the trillions of dollars required to support developing countries with clean energy transitions, implementing their national climate plans and adaptation efforts. To deliver on additional funding, the global stocktake (GST) underscored the importance of reforming the multilateral financial architecture and accelerating the ongoing establishment of new and innovative sources of finance. GST is considered the central outcome of COP28 as it contains every element that was under negotiation. Countries can now use it to develop stronger climate action plans due by 2025. Related discussions focused on setting a ‘new collective quantified goal on climate finance’ in 2024, considering the needs and priorities of developing countries. The new goal, which will start from a baseline of US$100 billion per year, is expected to be a building block for the design and subsequent implementation of national climate plans. The renewed focus on financial assistance was appreciated by developing countries but, these countries know that the goals set are largely aspirational and that the chances of credible financial transfers materialising are low.

The new goal, which will start from a baseline of US$100 billion per year, is expected to be a building block for the design and subsequent implementation of national climate plans.

Led by the European Union, the global pledge on renewables and energy efficiency called for tripling renewable energy capacity to over 11,000 gigawatts (GW) and increasing the rate of energy efficiency gains to 4 percent a year by 2030. This was received with enthusiasm by 130 countries that want a bigger role for renewable energy in decarbonising the world. However, China and India, two of the world’s top three emitters, are not among the signatories as they did not approve of the phrase that called for ending investments in unabated coal-fired power plants. Both China and India lead the table in building coal-based power plants. Of the 204 GW coal-fired power generation capacity under construction about 67 percent is in China and of the 353 GW coal-based capacity planned, 72 percent is in China with most of the rest in India. The 13 percent annual average growth of renewable energy capacity addition required to triple capacity by 2030 will remain a challenge as it is twice the growth rate achieved in the last 5 years. Efficiency improvement above 4 percent per annum this decade can reduce global energy consumption and emissions by a third but this will require more than tripling the rate of efficiency gains made in the last five years.

The agreement to triple nuclear energy capacity by 2050 delighted the nuclear industry but surprised traditional environmentalists. The call for transitioning away from fossil fuels in the GST received the approval of nearly 200 parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and was hailed by the UN as the “beginning of the end” of the fossil fuel era. But to the comfort of oil and gas producers and consumers which includes most of the world, the text of the agreement is vague and is not time-bound and fossil fuel production and use can continue on a business-as-usual path.

Over 50 national and international oil companies, representing about 40 percent of global production, signed an oil & gas decarbonisation charter. The charter aims to achieve net zero emissions in each company’s direct operations (as opposed to the use of their products) by or before 2050, to achieve near-zero methane leakage from the production of oil and gas by 2030, and to achieve zero routine flaring (burning excess gas) by 2030. The last two pledges are particularly important as methane is a more potent but short-lived greenhouse gas and a quarter of all man-made methane emissions come from oil and gas production.

India was not among the signatories of the COP28 declaration on climate and health on the grounds that the pledge lacked practicality in curbing greenhouse gases use for cooling in the health sector. However, China joined the list of signatories. India and China did not join the pledge to reduce cooling-related emissions across all sectors by at least 68 percent globally relative to 2022 levels by 2050, consistent with limiting global average temperature rise to 1.5°C and in line with reaching global net-zero emissions targets with significant progress and expansion of access to sustainable cooling by 2030. India aims to reduce its power demand for cooling across sectors by 20-25 percent by 2038 under its own cooling action plan announced in 2019. China refrained because it did not see accountability in previous such agreements. China and India’s selective approach to commitments is not defiance but conformity with the “nationally determined” character of climate action specified in the Paris Agreement.

India aims to reduce its power demand for cooling across sectors by 20-25 percent by 2038 under its own cooling action plan announced in 2019.

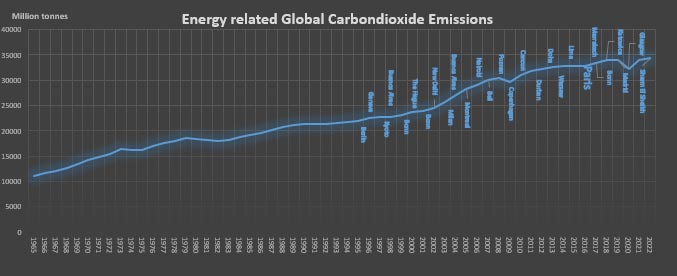

There were many more pledges and commitments that pleased some stakeholders but enraged others who pointed out the loopholes. For long-term and long distant observers of the COPs, the process and outcomes did not appear to have been robbed by any constituency, as it showed little or no deviation from the established path of all COPs. Similar most other COPs, COP28 offered something to every group but not enough for the world. Annual carbon emission increased by at least 4 billion tons during the two decades of COP meetings compared to the two decades before COP meetings. Only the economic slowdown caused by the global financial crisis in 2007-08 and the pandemic in 2020-22 managed to temporarily slow down carbon emissions. The final impetus for future carbon reduction will likely come from demographic decline complemented by technological progress rather than COP efforts.

The multiple tribes represented at COP28 fell under three broad categories: (A) a tribe that believes that economic growth driven by energy consumption, including energy derived from fossil fuels, is desirable and sustainable given the tribes’ skills & knowledge (commonly described as ‘business as usual’ approach) (B) this tribe is steadfast in the belief that the present trend is not sustainable and an orderly transition to a more sustainable future is possible through technology promoted by policy (C) a marginal tribe that believes that the present trend is not sustainable and only radical and dramatic political and social change will lead to a sustainable future.

At COP28 most of the assumptions were derived from Tribe B except for the equivalent of the ‘worst case’ assumptions that were derived from tribe A. Tribe B was the most articulate and audible of the three, with their respective ‘climate chiefs’ seen and heard every day. Members of tribe B made claims on public finances and resources to promote clean energy and reduce carbon emissions. Tribe B members were part of complex hierarchical organisations (state and non-state) that thought that equally complex and hierarchical needs and limits must be imposed upon systems and societies to go into a sustainable future. They allowed an increase in the share of the carbon pie for groups in the hierarchy, as long as it did not overtake the size of the pie for groups above them. In their view, nature is bountiful but only within accountable limits. However, the limits are different in the sense that there are different limits for different layers in the hierarchy. Ensuring differential limits required management of carbon emissions, their volumes and their flows which justified the authority of tribe B.

Tribe A could be seen to consist mostly of the businesspersons who saw the possibility of limitless growth of both the economy and energy. For them, nature is cornucopian but not free; it is accessed and controlled by their skill. Labelled and discarded as climate “deniers”, tribe B and C believed that keeping tribe A off the high table at COP was the only way out of the climate crisis. The presence of tribe A at the high table gave rise to the idea that the COP had been robbed. In reality, the presence of all tribes at COP 28 made climate action more democratic even if it did not yield desired outcomes for tribe B. In democratic processes, the sum is often lesser than the parts.

Source: Statistical Review of World Energy 2023

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Ms Powell has been with the ORF Centre for Resources Management for over eight years working on policy issues in Energy and Climate Change. Her ...

Read More +

Akhilesh Sati is a Programme Manager working under ORFs Energy Initiative for more than fifteen years. With Statistics as academic background his core area of ...

Read More +

Vinod Kumar, Assistant Manager, Energy and Climate Change Content Development of the Energy News Monitor Energy and Climate Change. Member of the Energy News Monitor production ...

Read More +