For electricity consumers in India, one of the most attractive proposals in the Electricity Amendment Bill (EA 2014) (yet to become law) is the proposal to introduce consumer choice in electricity procurement. Consumers presume that this will allow them to switch from state-controlled distribution companies (discoms) to private electricity suppliers just as easily as they do mobile telecommunications providers, largely based on the economic value proposition offered by various telecommunication service providers. For the government and electricity regulators, creating competition for the provision of electricity can lead to lower electricity tariffs in the short run. Additionally, introducing competition can create incentives to provide customers with new value-added services. However, introducing competition in electricity retail in India is not likely to be as straightforward as in the wireless telecommunications sector because of the unique features of electricity that require real-time matching of supply and demand. In addition, real-time will be muted as most discoms purchase most of their electricity on a long-term contract basis rather than through a wholesale electricity market that reflects the temporal and spatial value of electricity. Behavioural changes expected in electricity use by the consumer may not play out as anticipated without the intervention of technological inputs. If consumers are unwilling to switch suppliers, deregulated retail electricity markets will not become as desired.

Competitive Electricity Markets

In mature electricity markets that have competition at the wholesale and retail level, distribution companies other than the incumbent monopoly (which is also the distribution network owner) can purchase electricity through the wholesale market for electricity at rates based on the consumers load profile. Effectively the distribution company pays an average wholesale price for electricity load profile that is representative of the consumer class regardless of the actual pattern of the consumer and the relationship between the actual physical consumption and the real-time wholesale price of electricity.

However, if consumers do not participate actively in exercising choice, it can reduce the benefits of retail choice, even in mature markets. Households who are not used to retail choice may not exercise the option even if alternative suppliers offer lower prices. Some households may not actively seek information on electricity prices, and some households may also be attached to the brand name of the established monopoly supplier. These sources of friction can reduce consumer gains from retail choice.

Effectively the distribution company pays an average wholesale price for electricity load profile that is representative of the consumer class regardless of the actual pattern of the consumer and the relationship between the actual physical consumption and the real-time wholesale price of electricity.

There are several examples from western electricity markets that illustrate customer inertia in exercising the power of choice in electricity procurement. New Zealand, US, UK, Norway, Sweden, and Australia initiated electricity market reforms in the 1980s. These reforms aimed to replace monopolies with an efficient and competitive electricity sector, but success was limited, particularly in the retail electricity sector, where most consumers were reluctant to switch suppliers.

Norway and the UK who were early adopters of electricity reforms have been studied extensively. Most studies raised concerns about the competitive nature of retail markets and identified problems that were associated with a lack of active consumer participation and retail market concentration. In the mature and transparent retail market of UK, consumers often made suboptimal choices and switch to more expensive contracts. The British regulator, Ofgem, observed in 2011 that the competitiveness of the market had deteriorated in several dimensions and switching rates had dropped drastically. This outcome is attributed to the highly restrictive price interventions by the British regulator.

In the Norwegian retail market, coexistence of a very competitive market segment with low mark-ups and active consumers, and a monopolistic market segment where suppliers may exploit the consumers’ passivity was observed. In both markets, the top three electricity retailers had a market share of 70 percent or more. However, product innovation was observed in contract duration, additional services and sustainability. The key conclusion was that the transition towards a competitive and efficient retail market depended on the ability and the willingness of individual well-informed households to actively search for and select contracts that best fit their needs.

New Zealand introduced retail competition in 1998. The main objective was to increase consumer choice, encourage innovation, and ultimately result in lower prices than would otherwise be charged. In 2009, a ministerial review of the performance of the electricity market found that consumer switching rates were insufficient to curb non-competitive behaviour by retailers, and that the full benefits of retail competition had not been realised, particularly for domestic customers. It was observed that most electricity customers exhibited a tendency to stay with their default retailers even when cheaper competitors were available. Switching promotions were organised with the creation of switching websites, which acted as one-stop-shops by offering price comparisons and allowing consumers to switch to the cheapest available supplier. But switching websites and their extensive publicity proved ineffective at increasing switching rates in most regions, even during periods of rapidly increasing retail prices when substantial potential savings were available. Residential consumers faced rapidly increasing prices during the period 1985–2010, yet most consumers did not switch despite large price differences and entry of new suppliers into the retail markets. The relatively low switching rates resulted in insufficient discipline on incumbent retailer supplier leading to higher prices.

Switching promotions were organised with the creation of switching websites, which acted as one-stop-shops by offering price comparisons and allowing consumers to switch to the cheapest available supplier.

In 2002, residential electricity customers in Texas were allowed to choose their retail provider. Initially, all households were by default assigned to the incumbent. In every subsequent month, households had the option to switch to one of several new entrant electricity retailers. Though the incumbent electricity retailer’s price was consistently higher than that of new entrants, most households did not switch to alternative suppliers. If households had switched to suppliers who offered lower prices, it would have saved them about 8 percent of their expenditure on electricity. Four years after the introduction of competition the incumbent suppliers market share was over 60 percent.

Challenges for India

In most parts of India, consumers are connected to traditional electrical meters, and meters are read once in one or two months. Consumers pay per-kilowatt-hour (kWh) tariff that is independent of the actual timing of their electricity consumption. In most regions, the discom is the monopoly distributer of electricity and the discom purchases electricity on long term power purchase agreements (PPAs). The discom does not measure the realised consumption profile of individual consumers but rather the realised total consumption profile of all consumers in a given region. This information is used by the discom to make electricity purchase decisions. As the consumer is on a traditional electricity meter, there is no incentive to adjust consumption to peak and off-peak timings as only total consumption over a month or two is recorded. Effectively neither the discom nor the consumer make electricity purchase decisions on the basis of value of electricity at different times. The consumer does not pay more when consuming mainly at peak when electricity is more valuable rather than spreading consumption between peak and off-peak hours. As a result, the consumer consumes too much electricity when demand peaks (late evening) and too little off peak. Even without retail competition, consumers can move some of the electricity consumption to off-peak times, to reduce their electricity expenditure, provided electricity is priced according to value (more during peak hours and less off-peak hours). This will reduce overall costs for discoms and consumers will benefit from lower prices. However, if retail competition is prematurely introduced in India as proposed, small retail consumers (households) are unlikely to switch suppliers on a large scale because the transaction costs (time and effort) are likely to be high relative to benefits. Uniquely for India, if competition in electricity retail is introduced, it may force competition in wholesale markets. In most mature markets, it was the other way around.

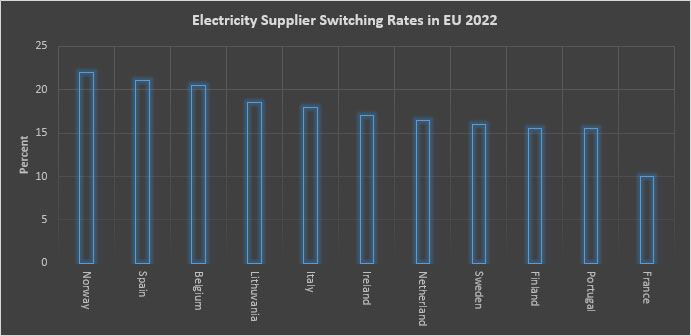

Source: European Union Agency for Cooperation of Energy Regulators; Note: only countries with switching rates above 10 percent are shown

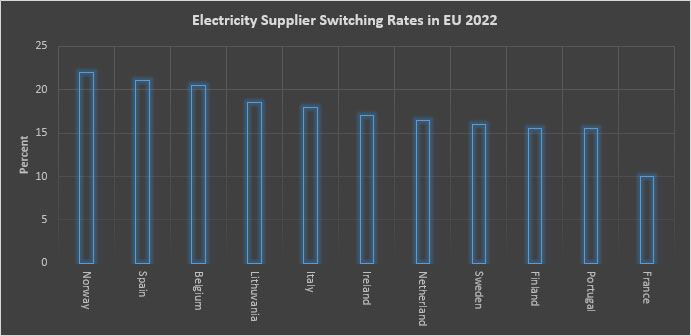

Source: European Union Agency for Cooperation of Energy Regulators; Note: only countries with switching rates above 10 percent are shown

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV