This article is part of the series Comprehensive Energy Monitor: India and the World

Coal stock shortage and the consequent power outages are dominating energy headlines in India. The widely cited cause is that logistical issues are holding up the transport of coal to power plants, whilst demand for power is growing with the summer heat. On 25 April 2022, coal stocks in 155 non-pithead thermal power plants were said to be 26 percent of their normative level, while 18 pithead power plants accounting for about 39 gigawatt (GW) generation capacity had adequate stocks. News reports quoting Coal India Limited (CIL) said that adequate amount of coal was available at washeries, sheds, and sidings, and power generators can transport coal by road as railway rakes are not available. Another report quoting the secretary, Ministry of Coal (MOC) said that the cause of the crisis in the power sector was not the supply of coal, but the sudden fall in power generation in many plants.

Logistics

In September-October 2021 there was a similar ‘coal crisis’ and media reports suggested almost the same causes: revival of demand following lifting of pandemic related restrictions, coal inventories going below critical levels in many thermal power plants, problems in availability of rakes to transport of coal by rail, and challenges in transporting coal during monsoon rains. The question that comes to mind is why these relatively straightforward managerial and administrative issues were not resolved in the last six months. Rake availability and transport are managerial and administrative issues that can be sorted out by the government, especially because both CIL and the Railways are publicly owned.

CIL is contractually obliged to deliver coal at the stock yard of thermal power generators and the excuse that rakes are inadequate is not sufficient to breach contractual obligations. Even if thermal power plants transport coal by road as demanded by CIL, power generators will not be able to pass on the additional cost to consumers immediately through an increase in tariff. Financially stressed discoms (distribution companies) would prefer outages to spot purchase of expensive power from power exchanges.

Some measures to address frequent coal-stock shortages have been announced recently. In April 2022, the Ministry of Power (MOP) allowed private power generating stations to secure coal supplies for up to three years instead of the current norm of one year to address the crisis in the power sector. The duration of independent power producers (IPPs) to bid for coal was reduced to 37 days from 67 days and the duration of supply was increased from one year to three years.

Demand

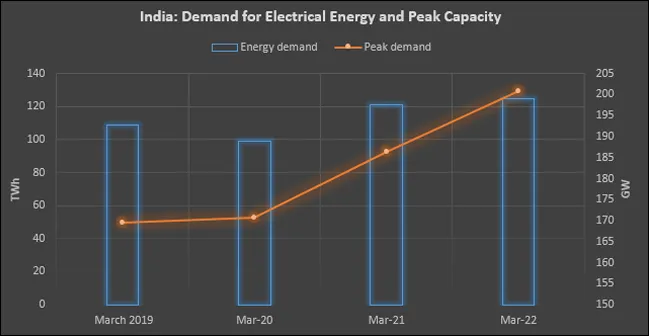

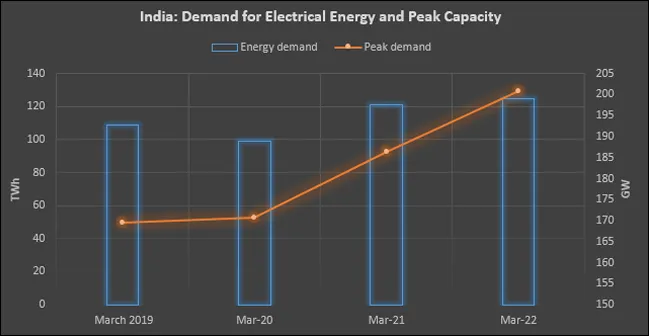

The observation that demand for power is growing needs to be looked at carefully. In March 2021, the electrical energy requirement was 121.205 TWh (terawatt hour), energy supplied was 120.635 TWh and the deficit was 0.5 percent. The peak demand in March 2021 was 186.389 GW and the peak met was 185.892 GW recording a deficit of 0.3 percent.

In March 2022, the energy requirement was 125.039 TWh and the energy supplied was 124.272 TWh with a deficit of 0.6 percent. In March 2022 the peak demand was 200.727 GW and the peak met was 199.288 GW recording a deficit of 0.7 percent. In March 2019, before the pandemic, the energy requirement was 108.665 TWh and the demand met was 108.196 TWh recording a deficit of 0.4 percent. The peak demand was 169.454 GW and the peak met was 168.75 GW. Compared to the pre-pandemic month of March 2019, demand for electrical energy in March 2022 has increased by over 15 percent and peak demand has increased by over 18 percent. Though this is a substantial increase, indications of substantial growth in energy demand were clear in 2021. Another key observation is that peak demand has increased substantially. This is a commercial challenge for power generators as it will require investment in capacity that is used only during relatively short durations of peak demand.

Global Headwinds

On 24 April 2022, roughly 8430 MW (megawatt) of thermal power generation capacity reported coal shortage as the reason for shut down (or forced maintenance). Thermal plants of about 22,057 MW capacity reported technical reasons for shut down, whilst thermal plants of capacity 4834 MW reported scheduled maintenance work as reason for going out of operation. This included nuclear power plants of total capacity 1,220 MW. Thermal plants of capacity 5,585 MW cited lack of power purchase agreements (PPAs) as the reason for not being operational and thermal plants of capacity 2,110 MW reported reserve shut down (RSD) as scheduled generation fell below the technical minimum. Thermal power generators holding 4 percent of total power generation capacity reported coal shortage as the reason for going offline, whilst over 10 percent cited technical reasons. Out of these many were designed for using imported coal. It is likely that these generators chose to go offline rather than use imported coal for which the price increase was substantial.

During the September 2021 coal crisis, the price of seaborne coal increased by over 950 percent compared to the price in September 2020 and the price of Asian LNG (liquefied natural gas) increased by over 420 percent driven by growth in demand for coal and LNG in Europe. In India the price of high quality imported coal increased 100 percent to INR14,600/tonne. Most of the imported coal based power plants either went offline or started using higher quality domestic coal. The result was a similar coal stock crisis in September 2021. In 2022, the revival of demand for energy followed by the crisis in Ukraine has pushed up imported thermal coal prices to over US$100/tonne. This is a challenge for thermal power generators in India who depend on imported coal. It is very likely that these generators are choosing to go offline rather than use expensive imported coal. What is clear is that the increase in the share of imported coal for power generation is exposing India to global headwinds of coal prices. This is affecting marginal demand for domestic coal that is driving the coal ‘coal crisis’ in India. Ironically, the government is suggesting the use of imported coal, most probably the key cause of the coal crisis in India, as the solution to the crisis. The more sustainable option is to allow electricity tariff to reflect the cost of fuel. The right price signal can increase supply and decrease demand for coal more efficiently than administrative interventions.

Source: Central Electricity Authority

Source: Central Electricity Authority

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV