Since the nationalisation of the Indian coal industry in 1971−73, the coal sector has been largely run by the Government. To address coal supply shortfalls, the Coal Mines (Nationalisation) Act of 1973 was amended in 1993 to facilitate the entry of the private sector to mine coal for captive use. Captive coal mining aimed to create space for private sector units not only to meet their own requirements but also to initiate green field projects that would otherwise not be developed by Coal India Limited (CIL). The blocks selected by CIL for allocation were mines with relatively more difficult conditions for mining and poorer infrastructure which CIL would not need in the next 50 years. A Steering Committee was set up for allocating coal blocks comprising of representatives from State and Central Ministries and CIL. There were no clear criteria set for the selection of applicants, so in the early years, blocks were allotted to those associated with Independent Power Producers (IPPs). State companies were allocated blocks directly by the Ministry of Coal (MoC) through ‘government dispensation’. Additionally, some blocks were allocated by the Ministry of Power (MoP) for UMPPs (ultra mega power projects) through competitive bidding.

Source: Coal Directory, Issues from 2007-08 to 2020-21

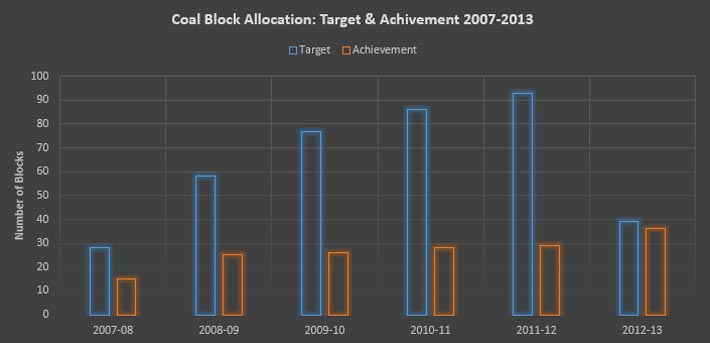

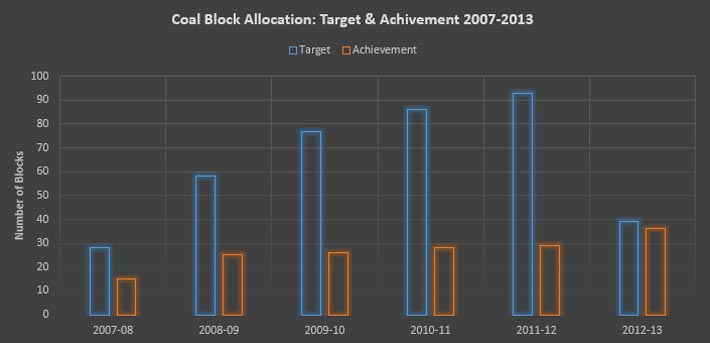

Between 1993 and 2011, a total of 218 coal blocks were allocated. 132 blocks were allocated by the screening committee (out of which 103 were allocated to private companies), 72 blocks were allocated under government dispensation, 12 blocks were allotted to UMPPs and two blocks were allotted for coal to liquid projects. The provision for competitive bidding was introduced through an amendment to the Mines and Minerals (Development & Regulation) Act 1957 (MMDR Act 1957) in 2010, and the rules for competitive bidding were introduced under the MMDR Act 1957 in 2012. 14 coal blocks were awarded to Public Sector Companies (PSU) in 2012-13 based on these provisions. Coal production by the private sector from captive coal blocks did not meet targets. Challenges in obtaining regulatory approvals along with the high investment required to develop coal blocks and related infrastructure in remote and difficult terrain, were among the reasons cited.

In August 2014, the Supreme Court of India declared the allotment of coal blocks by the Steering Committee and through ‘government dispensation’ as illegal and arbitrary. Consequently, the allotment of 214 coal blocks (barring 4 that were excluded from the ruling) was cancelled. Since 2015, these blocks have been in the process of being auctioned under the provisions of the Coal Mines (Special Provisions) Act 2015 (CMA 2015), enacted by the government that came to power in 2014. In March 2020, the Government of India enacted the Mineral Laws (Amendment) Act to remove the five-decade-old restrictions on commercial coal mining (The Mineral Laws (Amendment) Act, 2020). Auctions, as opposed to the allocation of coal blocks to the private sector, removal of end-use restrictions and the introduction of commercial mining, promised higher revenue for state and central governments and higher growth in coal production by the private sector.

Source: Coal Directory, Issues from 2007-08 to 2020-21

Status

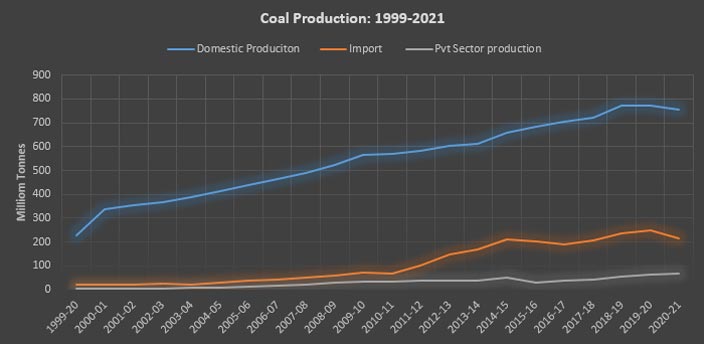

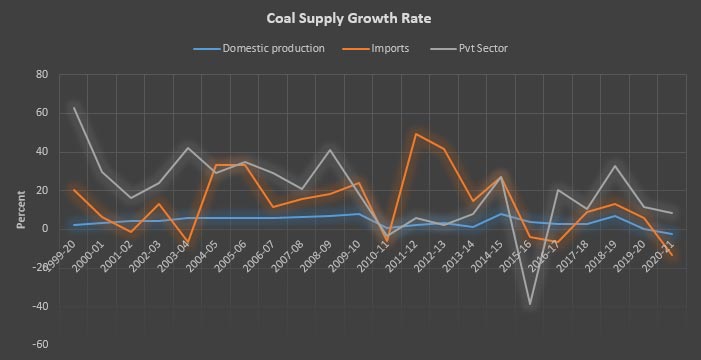

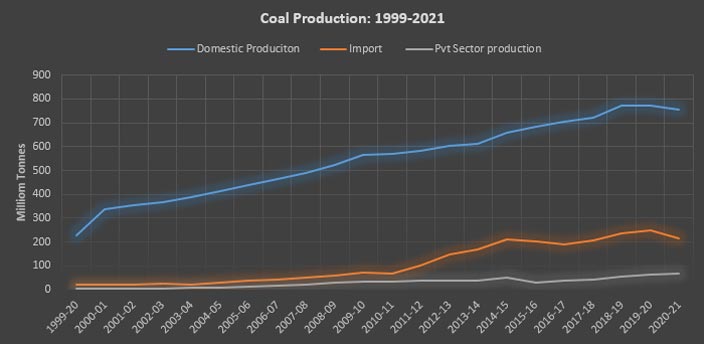

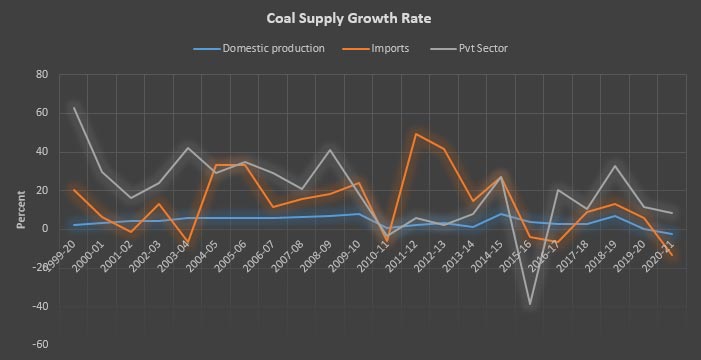

Since 1998, domestic coal production (coking and non-coking coal, including production by the private sector) grew by 3.7 percent from 319 million tonnes (MT) in 1998-99 to 753 MT in 2020-21.[1] In the same period, production by the private sector grew at an average of over 19 percent from 1.81 MT in 1998-99 to 66 MT. While the growth rate of private-sector coal production is impressive compared to production growth by CIL, the rate of growth in coal production by the private sector is falling. In 1998-05, private sector coal production grew by an average of 33 percent, albeit from a small base. In 2005-2014, a boom period for IPP (independent power producer) development and consequently coal production, the growth rate in private sector production was over 17 percent on average. In 2014-21, the average annual growth in coal production by the private sector slowed down to around 10 percent.

The share of private sector production in total coal production was 0.57 percent in 1998-99, and in 2020-21 it was about 8.8 percent. The annual average coal production by the private sector in 1998-2014 was about 18.8 MT. In 2014-21, annual average coal production by the private sector increased to about 49 MT. Coal production by the private sector started accelerating in the early 2000s when many IPP projects came on stream. In 1998-05 average annual coal production by the private sector was just around 5.2 MT. In 2005-2014, annual average production increased to over 29 MT.

While the growth in coal production by the private sector must be credited towards the promise of progress, it has not necessarily reduced the import of coal (coking and non-coking). Coal imports have grown from about 16.35 MT in 1998-99 to over 215 MT in 2020-21. Just before the pandemic in 2019-20, coal imports touched a high of 245 MT. Overall, coal imports have grown by an annual average of over 13 percent from 1998-2021.

Issues

In the 2010s, allocating coal blocks to the private sector formed the core of a political narrative of poor governance. The discourse on coal supply shortages in India was framed primarily as a problem of inefficiency arising from poor governance of the coal sector by the central government, the monopolistic structure of the industry dominated by CIL, a state-owned company and government policy of allocating coal blocks to the private sector that deprived the government of revenue. Ever-increasing volumes of imported coal, the low productivity of Indian coal mines compared to the productivity of mines around the world and the private sector profiting from free coal blocks substantiated the argument. Breaking up CIL into smaller independent companies to introduce competition, incorporating cutting-edge technologies to increase productivity, and opening up the sector to private players through competitive auctions were seen as obvious solutions. Opening up the coal sector to private players through competitive auctions was implemented as it was the solution that carried political momentum.

In retrospect, the auction argument appears to be inadequate. In a well-designed and open auction market, the social value of the coal resource would be approximately equal to the efficient firm’s valuation of it. But this is the ideal case. The price quoted in the auctions so far appears to reflect externalities (the cost) of past mistakes which means that it reflects private value (such as a firm having no other option but to get the block as it has invested heavily in end use) rather than social or national value. The reduction in the expected future value of coal production by the private sector has compromised the revenue argument.

While the inefficiency argument cannot be contested, a return to the origin of the problem can be traced back to the early 1990s when India opened up its economy, which offers some insights. In the early 1990s, India opened up product markets such as the market for electricity under external pressure but left factor markets such as that for fuels that generate electricity untouched. In the three decades that followed, product markets transformed beyond recognition but factor markets remained static. The pressure on the coal sector and, to a lesser extent in other fuel sectors may be seen as part of the broader pressure product markets are exerting on static factor markets. The mismatch between the pace at which factor markets (which includes the market for coal, land and capital in the context of the coal industry) and the pace at which product markets (which includes the market for electricity, steel, cement and other segments that use coal as input) are evolving is probably what we tend to see as inefficiency.

The fundamental crisis in the sector is not just the lack of transparency and the loss of revenue but rather the need for efficient markets for fuel that can keep up with the growth (or change) in the market for electricity, steel, cement and other coal-using segments. While competitive auctions have succeeded in correcting perceived past mistakes, it has not exactly set a clear course for the future. The policy is hinged in the past and oriented towards the present rather than being hinged in the present and oriented towards the future of the coal sector.

Source: Coal Directory, Issues from 2007-08 to 2020-21

Lydia Powell is a Distinguished Fellow at the Observer Research Foundation.

Akhilesh Sati is a Program Manager at the Observer Research Foundation.

Vinod Kumar Tomar is a Assistant Manager at the Observer Research Foundation.

[1] The data in this section is calculated from data in the issues of the coal directory of India from 2007 that were downloaded earlier. The website of the coal controller’s office that brings out the coal directory with links to all issues is currently offline.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV