-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

While it is increasingly clear that economies can simultaneously be green and grow rapidly, the shift to a new economic model requires both finance and technology.

This article is part of the series — India and the World in 2021.

The landmark Paris Climate Agreement signed by 195 countries — committing to limit global temperature increases to below 2 degrees centigrade above pre-industrial levels — came into effect in 2020. The global community’s actions in the coming decade will determine our success. Already, the current state of discussions suggests two broad trends that will play out over the next few years. For countries that have the financial resources, there is reason for hope. As policymakers recognise that environmental policy can support economic growth and development, climate action by governments, investors and companies could become far more ambitious. However, the risk of unequal, and therefore ineffective efforts to combat climate change is rising: wealthier countries have shifted focus to their domestic concerns and seem increasingly reluctant to support low-income nations that face financial and technological constraints to climate action.

In the first half of 2020, as the world grappled with COVID-19 and the nationwide lockdowns that sought to arrest the spread of the pandemic, policymakers faced little choice but to divert available resources to public health and the economy. Early stimulus announcements from the G20 economies were estimated to direct only 0.2 percent of spending to green sectors. The COP26 summit was postponed to 2021. Things started to change mid-year, as it became clear that the pandemic and its impacts would be more severe than initially anticipated. This, surprisingly enough, heightened political support for climate action. Policymakers finally began to understand the massive impacts that such shocks can have on growth, and the importance of building resilience into economic systems. Furthermore, given the necessity for government investment in restarting economies, the United Nations’ (UN) calls for “building back better” started to gain traction.

By the end of July, the European Union announced the biggest green stimulus in history, allocating around US$600 billion to climate action and making a pledge to become the first climate-neutral continent by 2050. Over the next few months, China, Japan and South Korea made similar pledges, bringing the number of countries committing to carbon-neutrality by the middle of the century to 110. This number is set to rise when the Biden-Harris administration takes the helm in the White House. Before 2020 ended, leaders from 75 countries came together to present updated commitments at the virtual Climate Ambition Summit (CAS) held to mark the fifth anniversary of the Paris Agreement.

The speeches at the CAS are an indicator of the direction climate action will take. At Paris in 2015, the narrative focused on the trade-offs between environmental sustainability and economic growth. In 2020, leaders recognised climate action as an opportunity to generate jobs and growth. It is a huge achievement — indeed, a testament to what could be possible when governments, finance and technology enter a virtuous cycle of policy, investment and innovation.

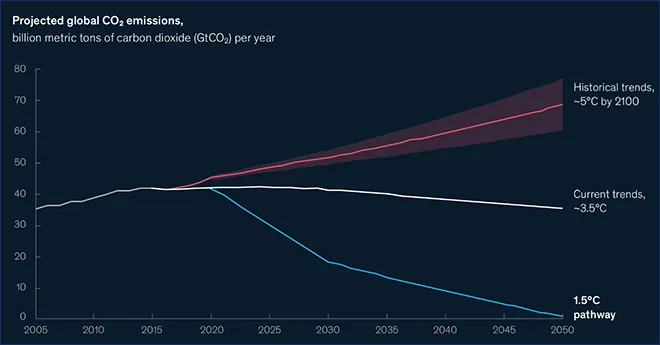

While current discussions around climate action tend to focus on how far we are from the 2-degree centigrade target, it is instructive to consider how far we have come. The figure below shows projected CO2 emissions up to 2050. The policies in place just five years ago would have led to emissions increasing consistently over the next three decades. Yet we are projecting a gradual decline till the middle of this century. As climate targets increase in ambition, emissions have plenty of scope to fall further to the 1.5-degree centigrade goal.

Source: McKinsey & Company

Source: McKinsey & CompanyIn the decade ahead, the shift to a low-emissions path appears increasingly viable. The pandemic brought travel to a standstill, and forecasts suggest that the demand for crude oil is unlikely to recover completely, peaking years earlier than expected. New transport technologies are maturing rapidly — not just electric vehicles, but hydrogen-powered ships and aircraft will provide clean alternatives for long-distance travel. Solar power is now the cheapest form of electricity in human history, and setting up new solar power plants costs much less than coal, even in developing countries like India. The implications for these countries, which need to build new power capacity, are huge: India will need 86-percent less coal up to 2040 than what earlier forecasts assumed. New investments in coal power are declining rapidly in developing Asian countries.

As new technologies scale up, their costs will decline rapidly. We can already see this trend at play, with Goldman Sachs estimating that the cost of reaching net-zero emissions by 2050 will cost US$1 trillion less annually than they had forecast in 2019. This is mainly due to rising demand, and the resulting increase in production, which has supported the creation of a connected ecosystem for decarbonisation.

Simultaneously, the funds allocated for sustainable investment are growing rapidly. Environmental, social and governance (ESG)-linked funds attracted net inflows of US$71.1 billion globally between April and June 2020, more than the combined flows for the previous five years. The market for green bonds has grown by 300 percent in five years, and is set to increase further as a number of countries issue green sovereign debt to finance recovery from COVID-19’s economic fallout.

As investors allocate funds on the basis of carbon footprint, companies will be forced to take action. The number of companies with net-zero emissions targets has grown three-fold since 2019, including some of the world’s biggest companies like Microsoft, Unilever and Amazon. Some have gone further, setting up funds for climate innovation. Governments are ramping up investment in clean energy and infrastructure, to ensure companies with net-zero targets continue to operate in their jurisdictions.

Most importantly for political leaders, ‘green’ economic activity favours the creation of more, and better jobs, making climate-friendly policies increasingly attractive to voters. Even the conservative IMF has encouraged a green investment push, despite elevated debt levels, stating that it will encourage job creation, raise demand, and fuel faster recovery.

While it is increasingly clear that economies can simultaneously be green and grow rapidly, the shift to a new economic model requires both finance and technology. While high- and middle-income countries are able to afford both, low-income countries sadly are not, and support for them is lacking. Out of the 175 countries that signed the Paris Agreement in 2015, only 75 were present in 2020, as the hosts offered speaking slots only to leaders who were prepared to present a new, more ambitious pledge. Going forward, a continued focus on unilateral, domestic commitments will constrain the ability of poor countries to implement climate-friendly policies.

Low-income countries, reeling from the COVID-19 crisis, cannot afford climate packages. The IMF, while stating that a global green stimulus will have positive spillover impacts, fails to remember that 80 countries have signed up for IMF programmes since April 2020, and 72 will have to cut spending starting in 2021. If these countries are to make new pledges, the developed world will need to commit resources in support of their implementation.

Unfortunately, the world seems to be forgetting that developed nations bear greater responsibility for this crisis. The question of mobilising resources for the developing world has been set aside, while domestic stimulus commitments continue. We must remember, however, that the combined emissions of the richest one percent of the global population account for more than the poorest 50 percent put together. We cannot expect all countries to cut emissions equally; a rebalancing will be required to ensure that the transition is just. The current attitude, however, tends towards excluding those who cannot keep up.

A good example is that of Brazil. In June 2020, as forest fires raged in the Amazon, a group of investors threatened to withdraw investments if they did not see action to preserve the forests. In preparation for the Climate Action Summit, the Brazilian government announced a pledge to protect the rain-forests and scale up climate commitments, if the world was willing to foot the annual bill of US$10 billion. This was widely seen as holding the world to ransom, and eventually led to Brazil being excluded from the summit.

While the sum of US$10 billion annually may appear outrageous, the opportunity cost of leaving resources unutilised needs to be acknowledged. The original Paris Agreement took these trade-offs into account, with 136 countries submitting conditional NDCs (Nationally Determined Contributions), which they would implement if provided with finance, technology and support in building capacity. India’s NDC, for instance, states that climate finance flows of US$2.5 trillion will be required upto 2030 to achieve the Paris targets. At current trends, the Finance Ministry estimates an annual shortfall of US$ 1140.66 billion by 2030.

While data on technology transfer and capacity building support are difficult to aggregate, statistics on climate finance flows show clearly that we are far from the US$100 billion per annum mobilisation that was promised at Paris. Even if the full amount was raised, it would support the implementation of only 23 percent of conditional NDCs. The proportion of this which reaches low-income countries is a paltry 8 percent. Prior commitments to increase climate finance flows to developing countries are at risk, as aid budgets have been cut across the board.

In order to advance towards global emissions targets, high-income countries need to be accountable for more than just domestic emissions. They will also need to ensure that developing nations have the support required to implement ambitious climate action. The COVID-19 crisis has already put us at risk of a two-speed world. Poor countries are much worse hit, both economically and socially, and likely to take longer to recover. Excluding those who cannot afford climate action will increase this divergence. But more importantly, it will not help us reach our goal. Climate change is a global problem, and ambitious pledges from half the world will fall woefully short if the other half is unable to keep up. The success of COP26 in 2021 should be measured by the extent to which it addresses the constraints faced by developing economies, instead of the scale of unilateral commitments announced.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Annapurna Mitra was Fellow at ORF. She led the Green Transitions Initiative at ORFs Centre for New Economic Diplomacy.

Read More +