-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

Climate change has become an even more pressing issue as it threatens public health, therefore, climate action needs to go beyond mere words

This piece is part of the series, Common But Differentiated Responsibility: Finding Direction In COP27

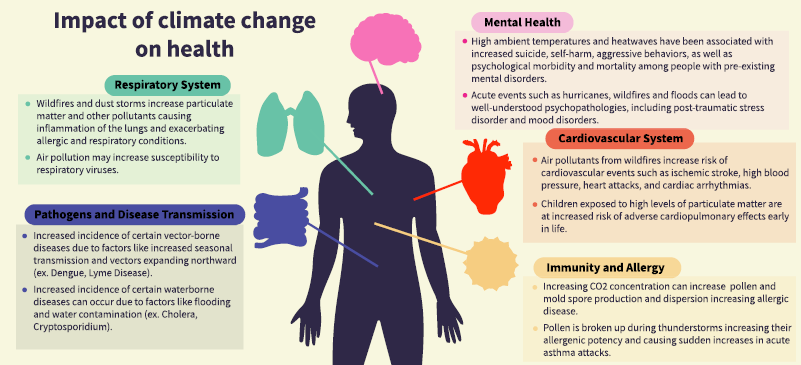

For the first time in history, there are three Public Health Emergencies of International Concern (PHEIC) ongoing in parallel: Monkeypox, COVID-19 and polio. Polio was declared a PHEIC way back in 2014. The United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) sixth assessment report (2022) observed that in Asia, climate change is worsening communicable diseases, undernutrition, mental illness, and allergies by increasing risk factors such as heatwaves, floods, drought, and air pollution (Figure 1). In addition to the direct impact on overall mortality, the risk of death related to a range of other conditions, especially among children, is impacted by high temperatures.

Figure 1: How climate change impacts health: The pathways

Source: I Agache et al (2022) DOI: 10.1111/all.15229

Source: I Agache et al (2022) DOI: 10.1111/all.15229

Experts suggest that every viral pandemic since 1900—including HIV, influenza, and COVID-19 were the result of “spillovers” of viruses from animals into humans. Given this, it is highly likely that the next pandemic could also have zoonotic origins. The likelihood of pandemics itself depends partly on climate-related environmental changes. Evidence indicates that the spillover of a number of emerging infectious diseases is associated with close human-animal interactions such aslive animal–human markets, mass livestock production and climate-induced movements of humans and animals into new areas.

Climate crisis is in many ways a health crisis both directly and indirectly. Apart from direct impacts on health, climate change undermines many key determinants of health, amplifying both morbidity and mortality burden. According to data from the World Health Organization (WHO), climate change affects social and environmental determinants of health such as air, drinking water, food security as well as safe housing. Between 2030 and 2050, 250,000 additional deaths per year are expected to result from climate change, due to undernutrition, malaria, diarrhoea, and heat stress. The direct monetary damage to health alone (excluding social determinant sectors), is expected to be between US$2 to 4 billion per year by 2030.

Climate crisis is in many ways a health crisis both directly and indirectly. Apart from direct impacts on health, climate change undermines many key determinants of health, amplifying both morbidity and mortality burden.

The IPCC report also observed that increases in both rainfall and temperature will increase the risk of a range of communicable diseases in tropical and subtropical Asia. A number of heat-related deaths is bound to increase in Asia due to higher exposure. Additionally, these factors will have an adverse impact on food security in South and Southeast Asia. However, the ongoing multiple health crises have severely impacted collective efforts on climate action.

Described above is the broad regional context within which COP27 of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) is being held in Sharm el-Sheikh in Egypt. In the run-up to COP27, the Lancet Countdown report on Health and Climate Change was published in October 2022, which explored the health impacts of climate change amidst a cost of living and energy crises.

The report found that during the last two years, extreme weather events caused devastation across the world, adding further pressure to stressed health services already grappling with the impacts of the pandemic. It was found that temperatures unprecedented in history were recorded in many countries during 2021-22, including in India. The report asserted that a business-as-usual trajectory of actions is insufficient to reach the 1·5°C target.

The report estimated that annual heat-related mortality of the elderly population (those older than 65 years) increased by 68 percent between 2000–04 and 2017–21. In parallel, heat exposure had a devastating impact on economies by contributing to productivity decline. According to the report, it led to a decline of 470 billion potential labour hours in 2021, with equivalent to 0·72 percent of the global economic output in income losses. The income losses disproportionately increased to 5·6 percent of the GDP when it came to low Human Development Index (HDI) countries.

Pointing towards the experience of the French health system, the report argued that quality health and lower emissions are not mutually exclusive.

The global increase in temperatures has impacts on vector-borne diseases as well. The Countdown report found that the time period suitable for malaria transmission rose by 31·3percent and 13·8 percent in the highland areas of the Americas and Africa respectively between 1951–60 to 2012–22. In parallel, the risk of dengue transmission also increased by 12 percent. The report found that the threat of extreme weather on crop yields puts pressure on supply chains and contributed to food insecurity.

The report acknowledges that older adults, people with cardiovascular disease, the poor, and people isolated in low-cost housing are exposed to the highest risk of heatwaves and calls for sustainable and affordable cooling alternatives. Across the world, the use of ‘dirty fuels’ causes air pollution, as around 770 million people with no electricity at home have no alternative. Lancet estimated that in 2020, fine particulate matter (PM2.5) pollution contributed to 3·3 million deaths, more than one-third of which were directly linked to fossil fuels. The report recommended that decarbonisation is an urgent priority with direct and indirect benefits.

Interestingly, the report found that in 2019, the healthcare sector itself contributed approximately to 5·2 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions, a rise of more than 5 percent from 2018. This proportion could have possibly only gone up in the following years given the multiple crises putting unprecedented strain on health systems. Pointing towards the experience of the French health system, the report argued that quality health and lower emissions are not mutually exclusive. The report also recommended shifting to a more vegetarian diet, as more plant-based diets could bring down 55 percent of agricultural emissions contributed by red meat and milk production, and reduce zoonotic disease risks. However, access to cheap sources of animal protein remains key for food security within many developing countries.

Despite the depressing statistics presented across the text, the Countdown report argues that a health-centred climate response may have started to emerge globally. Supporting evidence presented shows coverage of health and climate change-related content in global media reached a record high in 2021, with a 27percent rise from 2020. Correspondingly, possibly fueled also by the media coverage, citizen engagement with health dimensions of climate change also increased between 2020 to 2021. This accelerated engagement is also reflected among the national political leadership, with a record 60 percent of 194 countries focusing on –health-climate change linkages in the 2021 UN General Debate, and 86 percent nationally determined contributions (NDCs) documents referring to health.

Supporting evidence presented shows coverage of health and climate change-related content in global media reached a record high in 2021, with a 27percent rise from 2020.

While the evidence presented by the Lancet Countdown report to set the terms of the debate during the year ahead starting with COP27 is indeed concerning and the demand for corrective action is unexceptionable, there are concerns about the means being used to achieve those ends. Debates around climate change action and energy access in the emerging economies are complex, interlinked ones, rarely black or white. Experts have argued how developing countries that have contributed the least towards historical global emissions are often left to fend for themselves, as climate change is seen as a collective global burden, and key trade-offs are ignored.

Health and climate change coverage in the media is great; however, there may need to be some reflection on the kind of factoids being popularised as part of the media blitz around efforts like the Lancet Countdown report. For example, the media coverage of the Countdown report in India almost exclusively revolved around the claim by the report that heat-related deaths among vulnerable elderly populations in the world increased by 68 percent between 2000–04 and 2017–21 because of the rapidly increasing temperatures. The India specific data in the report, claimed that the corresponding increase in India was 55 percent amounting to additional 11,020 deaths among the elderly.

However, experts have since questioned this statistic, as to why absolute numbers and not death rates are used, given the fact that over the same time period, India’s elderly population increased from 5.1 crore to almost 9 crore, an increase of 76 percent. They argue that when corrected for the growth of the elderly population, heat deaths for India would have actually declined from 39.5 per lakh to 34.8 per lakh, a reduction of 12 percent, and not an increase of 55 percent as the Countdown report claimed. Interestingly, this glaring omission was in the previous year’s Countdown report as well, and was brought to the Lancet’s attention. Climate change-related evidence should trigger nuanced discussions in the countries if systems are to be strengthened. Coverage of the Countdown report in India could have been a time when the expected changes in the transmission dynamics of diseases like malaria due to climate change are discussed. However, the report mentions only the regions where the number of months suitable for malaria transmission has increased dramatically, something that has dominated media coverage as a universal fact. However, a closer look at other sources like the IPCC report shows that there are indeed regions—within India and Southeast Asia, for example—where distribution of mosquitoes causing malaria may in fact decrease due to the same reasons.

Coverage of the Countdown report in India could have been a time when the expected changes in the transmission dynamics of diseases like malaria due to climate change are discussed.

In India, there may not be a blanket increase or decrease of malaria due to climate-induced reasons, but a change in the distribution of the disease itself. IPCC report presents projected scenarios for the 2030s suggesting a shift in malaria-prone areas, with the Himalayan region, southern and eastern states acquiring a higher risk profile. An overall increase in time period suitable for transmission is expected in these regions, with some other current hot-spots experiencing a corresponding reduction.

Experts like Bjorn Lomborg argue that selective presentation of numbers is deliberate to alarm stakeholders and possibly strong-arm a policy response. He argues that globally, far more people die each year from cold than heat (cold deaths globally outweigh heat deaths 9 to 1), and cold deaths are in fact decreasing with rising temperatures. Indeed, temperatures rose throughout the last century, but the United States saw a decrease in heat deaths. Lomborg cites a study from 2016 which proves that residential air conditioning explained most of the decline. Energy security is a major piece in the heat mortality puzzle.

Do the developing countries need to be tricked into taking action against an existential problem like climate change? This question needs to be answered along with the one on historical emissions. A review published in 2022, which explored both direct and indirect health impacts of climate change found that the impacts are mediated by vulnerability and increasingly by the broader economic, political, and environmental context.

A lot of health policy discussion at COP27 is around the Alliance for Transformative Action on Climate and Health (ATACH) launched at COP26 last year, which works to realise the ambition to build climate-resilient and sustainable health systems and promote the integration of climate change and health nexus into respective national, regional, and global plans.

India’s climate goals are ambitious and cautious at the same time, as the updated nationally determined contributions signify. In parallel, putting the focus on access to reliable and affordable energy to the vast population, India has said it will not be moving away from coal in the foreseeable future. A lot of health policy discussion at COP27 is around the Alliance for Transformative Action on Climate and Health (ATACH) launched at COP26 last year, which works to realise the ambition to build climate-resilient and sustainable health systems and promote the integration of climate change and health nexus into respective national, regional, and global plans.

India has not yet chosen to be a member of ATACH. Expansion of currently inadequate healthcare delivery systems may indeed lead to a higher carbon footprint for the sector. Given that the Countdown report mentions India approvingly in contrast to the United States which has 50 times per person healthcare sector specific emissions, the country will have to find ways to navigate the climate debate to make sure deprivation is not normalised or even glorified by institutions dominated by Western interests. While wildfires from climate change are important and need to be addressed, India may also have other burning issues with very high potential impact on population health to address through innovative policymaking, like crop fires.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Oommen C. Kurian is Senior Fellow and Head of Health Initiative at ORF. He studies Indias health sector reforms within the broad context of the ...

Read More +