The year 2023 was recorded as one of the hottest years in the past two centuries. Extreme weather events like heatwaves, flash floods, droughts, and wildfires have accompanied increasing temperatures. The impact of climate change is vividly visible with heat stress, rising sea levels and warmth, acidification of rains, glacial and permafrost melts, and other extreme events jeopardising the future of ecosystems essential for sustaining life. This has prompted the need for immediate and effective actions to ensure damage control. The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) has chosen “At the Frontline of Climate Action” as the theme for the 2024 World Meteorological Day, which is annually observed on 23 March.

The impact of climate change is vividly visible with heat stress, rising sea levels and warmth, acidification of rains, glacial and permafrost melts, and other extreme events jeopardising the future of ecosystems essential for sustaining life.

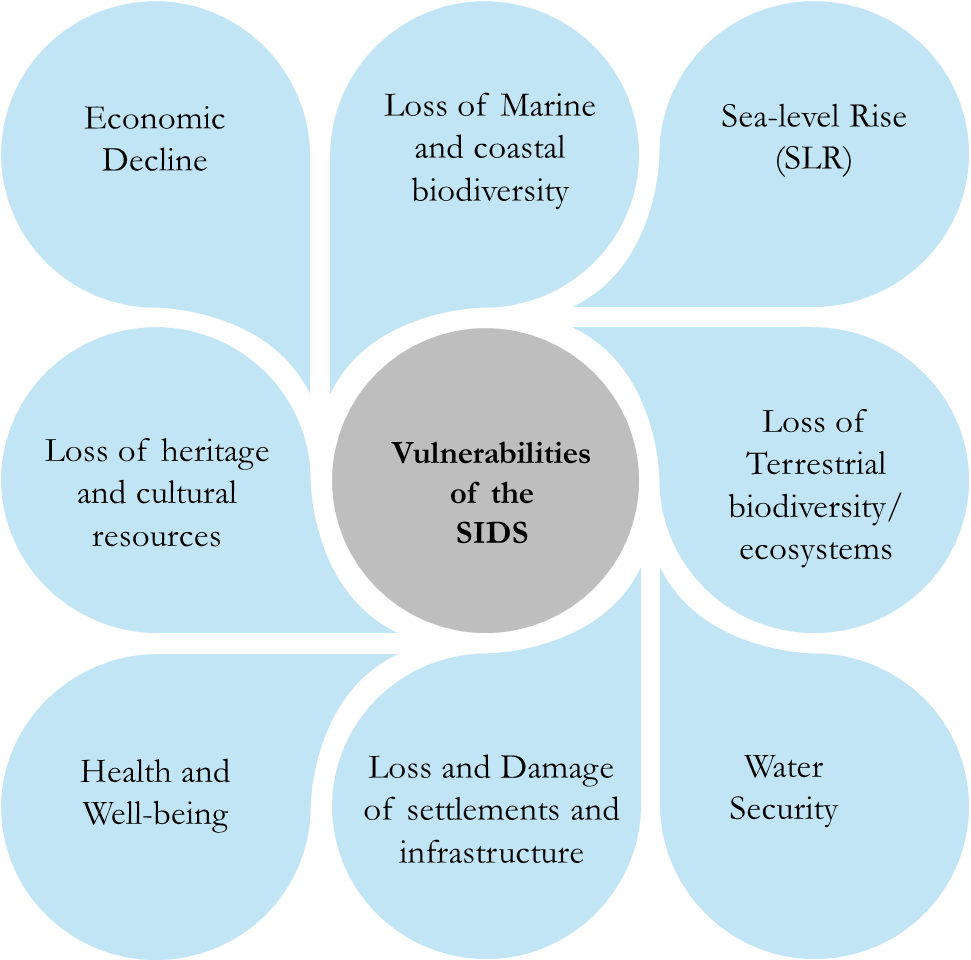

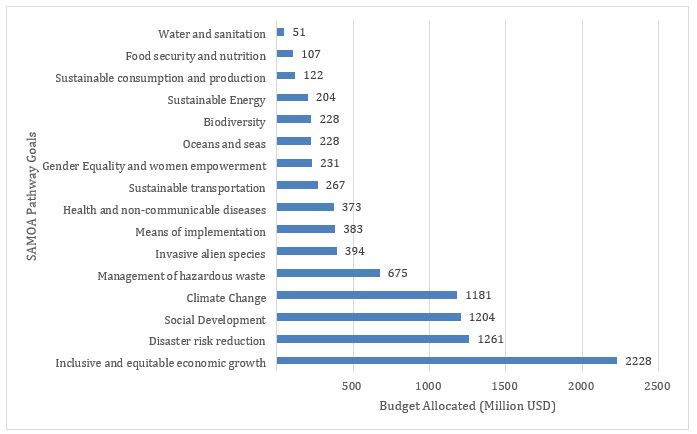

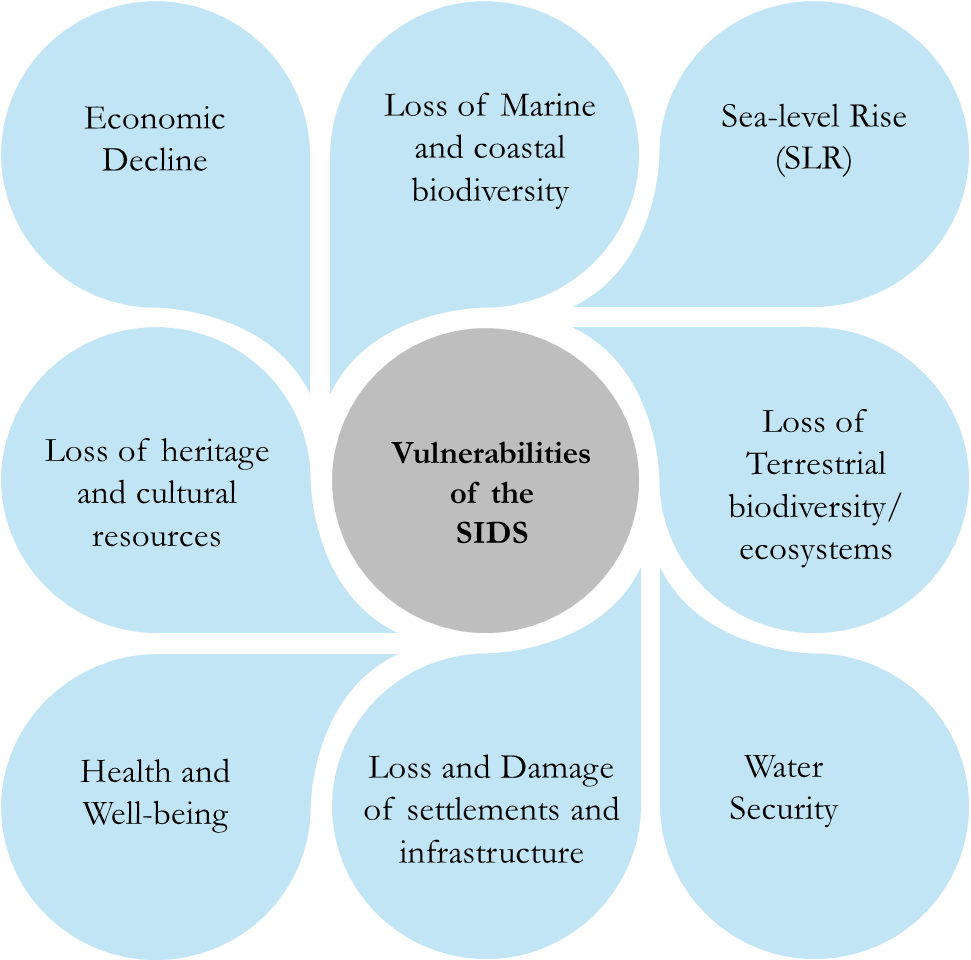

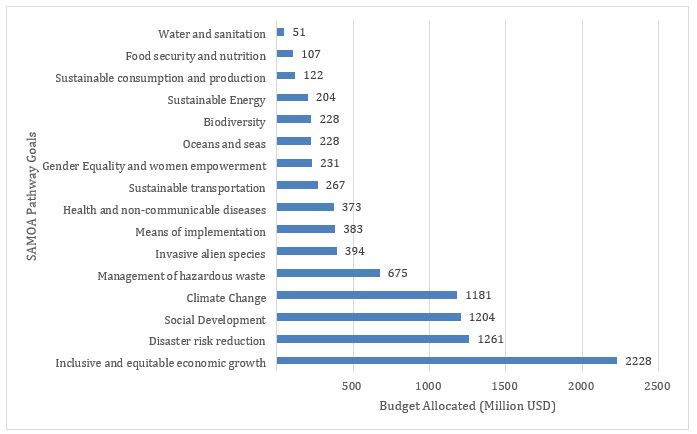

Changes in the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events associated with climate change threaten the reversal of socioeconomic development achieved over the past decades. However, this effect disproportionately impacts the Small Island Developing States (SIDS) compared to larger landmasses due to their remoteness, small and scattered land area and population, import dependency, limited development access and differential climate vulnerabilities (Figure 1). While a heterogeneous group, the SIDS have collectively voiced their concern about being worst affected despite their low contribution to climate change. This has resulted in some key initiatives such as the Barbados Programme of Action (BPOA), the Mauritius Strategy, the Bali Roadmap, and the SAMOA Pathway, to aid the SIDS. Figure 2 depicts the budget allocation of the SAMOA Pathway over the years which indicates a considerable investment by the international community in tackling climate change, social development, disaster risk reduction, and inclusive growth in SIDS. Despite the presence of such initiatives and increasing international climate aid to these states the lack of efficient governance, financial management, awareness, and human capacity have hampered the implementation of responses.

Figure 1: Interconnected Risks of the SIDS identified by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC):

Source: OECD

Figure 2: Budget Allocation of SAMOA Pathway Goals

Source: United Nations Development Programme (UNDP)—SIDS Portfolio

The discussion on SIDS becomes imperative not only due to the extent to which they are affected by climate change but also their possession of massive ocean areas and resources. For instance, Tuvalu which has a land area of 26 km2, has an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) of 900,000 km2. The EEZs under the jurisdiction of the SIDS control 30 percent of all oceans and seas. Thus, this provides the SIDS with enormous blue economy potential with bigger states wanting their partnerships for food and deep-sea minerals. Furthermore, the strategic location makes them crucial for maintaining critical sea lanes. Their geographical location which entails vital shipping routes has resulted in a scramble for their valuable support as key outposts for docking and refuelling both commercial and military vessels. For instance, the SIDS in the Indo-Pacific region provides easier access to the strategically important Sea Lines of Communication (SLOCS) and major chokepoints making engagement with these states key to boosting maritime presence. While the developed countries intend to partner with SIDS for geoeconomic and geopolitical gains, the global community must enable these islands to mitigate, adapt, and ensure resilient measures are in place to tackle the effects of climate change on vulnerable states.

The SIDS in the Indo-Pacific region provides easier access to the strategically important Sea Lines of Communication (SLOCS) and major chokepoints making engagement with these states key to boosting maritime presence.

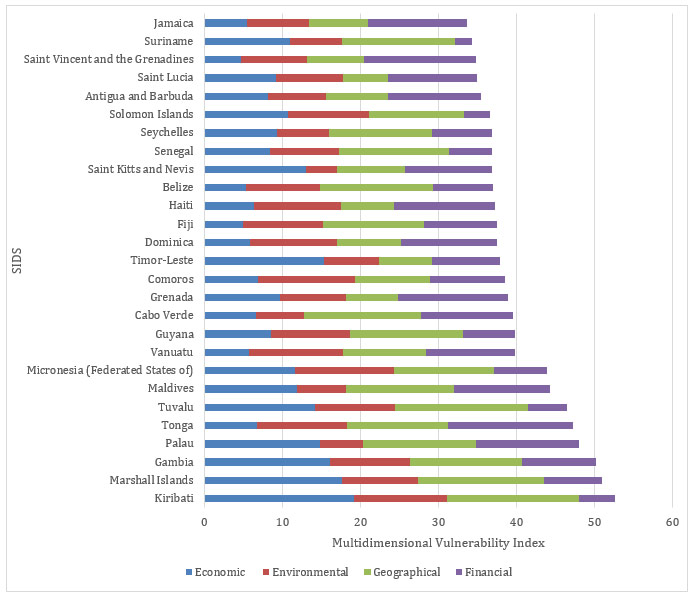

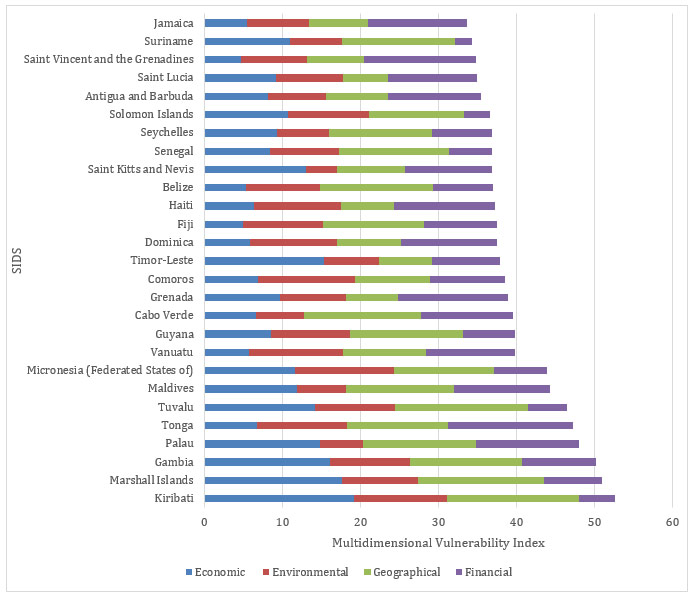

The Multidimensional Vulnerability Index (MVI) developed by the United Nations Development Programme indicates the environmental, geographic, economic, and financial risks and is used to assess eligibility for concessional financing. Figure 3 depicts the MVI of 34 SIDS highlighting that 82 percent of them are highly vulnerable. Additionally, there is a need to incorporate the health dimension in assessing the vulnerabilities of SIDS as they carry a high burden of climate-sensitive diseases, due to acute long-term risks, and lack of access to healthcare, food, and water. During the Fijian presidency of COP23, a special initiative on climate change and health in SIDS was initiated in association with the United Nations Climate Change Conference, WHO and the UN Climate Secretariat to build climate-resilient health systems in these vulnerable states. There is an urgent need to integrate meteorological information in the health surveillance data in SIDS as it could enable in creation of appropriate preparedness and response strategies to health risks by national authorities and the international community. The UAE Declaration of Climate and Health during COP28 recognised that the need to integrate health concerns into the global climate change agenda can catalyse the initiatives of SIDS.

Figure 3: Multidimensional Vulnerability Index

Source: UNDP

To tackle the disproportionate exposure to the climate crisis that threatens health in the SIDS, particularly in the states where healthcare services are limited, there is a need to improve the integration of Primary Health Care (PHC) and Universal Health Coverage (UHC) with emerging health threats including NCDs and mental health. Further, there is a need for a multi-sectoral approach to address the climate-induced health concerns in SIDS by increasing the participation and agreements between ministries of health and other sectors. Additionally, there is a need to utilise initiatives such as the WHO-WMO Joint Climate and Health Programme to build knowledge to train and mobilise dedicated personnel to enhance the protection of health from climate change and extreme weather. The six building blocks and WHO Operational Framework for Climate Resilient Health Systems must be effectively employed to address the vulnerabilities and cope with climate variability for continued service. However, the success of these initiatives requires political, technical, and financial support to the SIDS.

While the magnitude of international finance for climate action has increased gradually, particularly in the form of concessional loans and grants, there is a need to explore enablers such as microfinance and insurance, which could help prepare, respond, and build resiliency from external shocks like COVID-19. Further, there is also a need for climate-proofing the domestic economies of these island states from external shocks. Owing to small populations and remoteness, integration into global value chains or benefits of economies of scale could enhance the management of their existing ocean economy sectors while harnessing newer opportunities could help in diversification. For instance, Seychelles has created the Seychelles Blue Economy Strategic Framework and Roadmap, for sustainably using EEZ. Similarly innovative finance mechanisms such as the blue bonds launched in 2018 have helped mobilise funds for sustainable marine and fisheries projects. However, making effective decisions requires guidance at the country and regional levels, where the multilateral organisations could fill in to enable a stakeholder-driven process.

Owing to small populations and remoteness, integration into global value chains or benefits of economies of scale could enhance the management of their existing ocean economy sectors while harnessing newer opportunities could help in diversification.

Multilateral forums like the Quad, G20, and Pacific Island Forum, with their initiatives such as Q-CHAMP, LiFE, and 2050 Strategy for the Blue Pacific Continent, play a crucial role in increasing deliberations on access to quality and relevant data, interpretation of weather patterns, forecasting, and infrastructural development. Enhancing transport resilience with the help of the global community can reduce the loss and damage to critical assets like roads, runways, and docks since their operational ability also impacts well-being and recovery operations. Helping in mapping hazards, identifying vulnerable assets, and analysing the impact of asset failures are some key areas where international or regional cooperation could prove vital. Additionally, developed countries can aid effective climate action by helping to align multilevel governance and institutional frameworks through political commitment. Effective governance helps to develop inclusive, transparent and equitable decision-making as well as access to climate finance and technology. A SID-led engagement with responsible ownership from bigger countries could lead to meaningful consultations while ensuring efficient participation from various stakeholders.

Being at the frontlines of climate change, the measures taken by SIDS are unable to keep up with the pace of increasing climate risks. Other challenges such as oil spills, food and water security, and illegal, unregulated, and unreported (IUU) fishing must also be addressed with a long-term vision. Frameworks and measures such as the Paris Agreement, Sendai Framework, and the IPCC call for progressive response and solutions intended to address climate variability. However, due to the inherent limitations of SIDS, international cooperation and community play a crucial role in developing a comprehensive approach, capacity building, and enhancing the organisational and systemic capacities that complement domestic measures to overcome gaps.

Kiran Bhatt is a Research Fellow at the Centre for Health Diplomacy Department of Global Health Prasanna School of Public Health Manipal Academy of Higher Education.

Aniruddha Inamdar is a Research Fellow at the Centre for Health Diplomacy Prasanna School of Public Health.

Sanjay M Pattanshetty is Head of the Department of Global Health Governance at Prasanna School of Public Health Manipal Academy of Higher Education (MAHE) Manipal Karnataka India.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV