The Chinese reiteration of its claim to a large chunk of eastern Bhutan could well be a message to India. Though China has claimed areas of northern and western Bhutan since the 1950s, the eastern claim has never been pitched directly till now. The reason is that this claim is linked to Beijing’s demand that India return the Tawang monastery and its surrounding area to China as part of any overall settlement.

China’s signal came through its attempt in early June to get the Global Environment Facility of the UNDP to stop funding activities in Bhutan’s Sakteng sanctuary in eastern Bhutan on grounds that it was “disputed territory.” Then, days after Bhutan protested the Chinese move,

Beijing doubled down on its claim and made an official declaration: “The boundary between China and Bhutan has never been delimited. There have been disputes over eastern, central and western sectors for a long time,” through a statement of the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

The fact that this position emerged in early June at a time when China was locked in a series of stand-offs along its Line of Actual Control (LAC) with India, suggests that it has an India connection.

The statement was strange, but characteristic. Beijing has suddenly changed goalposts for reasons best known to itself. There have been 24 rounds of negotiations between China and Bhutan over their border, the last in 2016, but the eastern sector had never been raised before. This is not unlike what China did in informing India in 1959 that the entire border was disputed. It did the same with Vietnam with regard to the Paracel and Spratly Islands, and Japan in connection with the Senkaku islands.

Talks between China and Bhutan over their 470 km border have been taking place since 1984, but Chinese claims go back earlier.

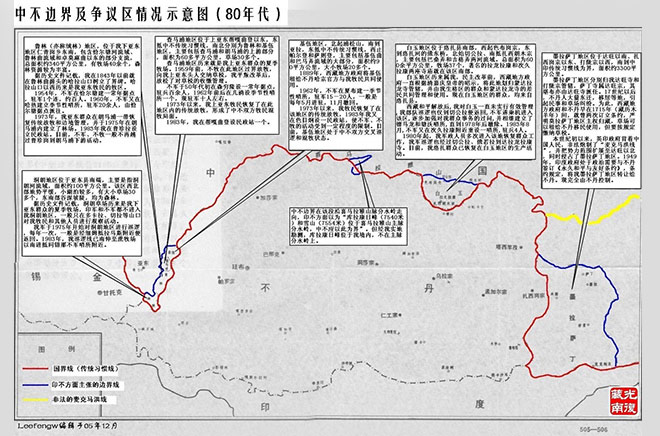

According to the scholar Medha Bisht, since the 1950s, China has published maps claiming Bhutanese territory. These covered some 764 sq kms, which included 269 sq km in the north western areas, 495 sq kms in north central Bhutan. The north western areas included Doklam, Sinchulung, Dramana and Shakhatoe. The central part covered the Pasamlung and Jakarlung Valleys (See Map 1 below). There was no reference to any eastern dispute which the Chinese, which now says covers 3,300 sq km of the Bhutanese territory in the extreme east.

(Map 1)

(Map 1)

This is borne out by the fact that in 1997, the Bhutanese king told the 75

th session of the Bhutanese National Assembly that the two sides were discussing

a Chinese proposal for an exchange of the Pasamlung and Jakarlung valleys with Bhutan’s western claims. The Chinese were clearly targeting the western areas which would help them enlarge the narrow Chumbi Valley and also give them a bird’s eye view of the Siliguri Corridor through Doklam. China came close to swinging this deal in 2001, but then things changed.

The hidden hand behind Bhutan’s refusal to compromise with Beijing has, of course, been India, which was not interested in easing China’s strategic concerns over the Chumbi Valley, nor in enabling them advantage through the acquisition of Doklam. Bhutan has gone along with India in refusing any compromise till now, though

there are some voices there calling for the country to settle as soon as possible. India’s leaning on Bhutan in 2012, using LPG subsidies as a lever, has not been forgotten. This was said to be a somewhat heavy-handed expression of unhappiness over the meeting between Bhutan’s Prime Minister Jigme Thinlay and his Chinese counterpart Wen Jiabao at the Rio +20 summit on sustainable development in Brazil the same year.

However, Bhutan has been accommodating to its northern neighbor by forgoing another significant claim of the area around Kula Kangri in the north. Bhutanese officials acknowledged in 2009 that their claim had been based on erroneous maps.

As in the case of India, the border negotiation have now got into an endless loop underscored by the signing of the agreement to Maintain Peace and Tranquility on the Bhutan-China border areas in December 1998. Clause 3 of the treaty committed the two sides to maintain the status quo on the border areas. However, Beijing has cared little about this commitment and has been building roads in what is Bhutanese territory. It was in building such a road in Doklam that triggered the 2017 crisis between India and China.

In a July 2017 blog post on the sina.com site, which

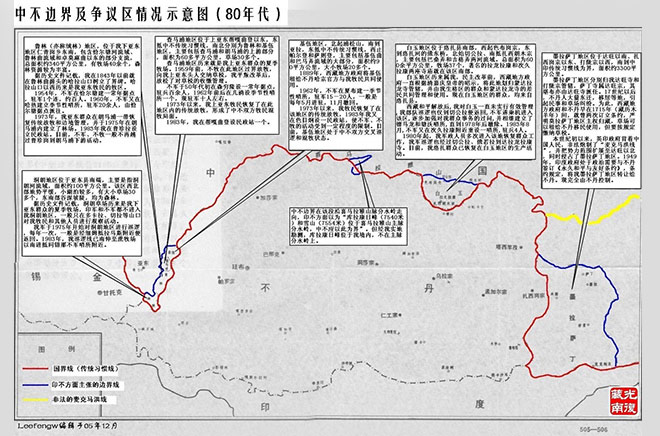

has since been encrypted, the disputed borders between Bhutan and China have been depicted (Map 1 and Map 2).

(Map 2)

(Map 2)

There are seven items mentioned in the map (Map 2) that purports to show the Chinese version of the Bhutan-China boundary in red and the Bhutanese version in blue. The line in yellow is the Sino-Indian boundary in the Tawang area. The origin of the map is not clear, though it says it is from the 1980s.

The first six items beginning from the left refer to the well-known differences in the boundary relating to Doklam, Dramana, Shakhatoe, Pasamlung and Jakarlung areas. What is of interest is the box on the extreme right, which is linked to the eastern region where the Sakteng wild life reserve, which has triggered this most recent controversy, is located.

The translation says this area is termed as the “Molasading Disputed Area”, which is south of Tawang and comprises of 3,300 sq kms. The item notes that the area was brought under the jurisdiction of the Tawang monastery and the Dalong district and the Sading temple there belonged to Tawang monastery that appointed its spiritual head. It claims that the Bhutanese only moved into the area in the 17

th century. It also claims that in 1949, India transferred the Molasading region to Bhutan as per its Permanent Peace and Friendship Treaty.

The text of the treaty, though only speaks about the return of a very small tract of land adjacent to Kamrup, called Dewangiri.

“Moladsading” cannot be located in Google Maps and neither the “Sading Temple.” Incidentally, the article itself suggested that China had maybe given up its claim to the area. But that was in 2017, and the piece was on the Weibo by an obviously pseudonymous writer. Even Bhutanese maps show the area as being largely forested and known for its wildlife sanctuaries, and nothing else.

As of now, there are no formal diplomatic relations between China and Bhutan, and the affairs are handled via the Chinese embassy in New Delhi. High level delegations of the two countries have visited each other

and Chinese tourists, too, visit Bhutan. Border talks have been held in each other’s countries, though there have been none since the 24

th round in 2016. It remains to be seen if Beijing places the eastern sector, too, on its agenda for negotiations.

The last set of senior officers to visit Bhutan were Vice Foreign Minister Kong Xuanyou, who made a two-day visit to the country in July 2018, a year after the Doklam standoff. The former Chinese Ambassador to India, Luo Zhaoui, visited in January 2019 and his successor, Sun Weidong, in November the same year. Luo who had dealt with Bhutan in mid 2005 as the Deputy Director of the Department of Asian Affairs in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, has since become a Vice Foreign Minister.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

The Chinese reiteration of its claim to a large chunk of eastern Bhutan could well be a message to India. Though China has claimed areas of northern and western Bhutan since the 1950s, the eastern claim has never been pitched directly till now. The reason is that this claim is linked to Beijing’s demand that India return the Tawang monastery and its surrounding area to China as part of any overall settlement.

China’s signal came through its attempt in early June to get the Global Environment Facility of the UNDP to stop funding activities in Bhutan’s Sakteng sanctuary in eastern Bhutan on grounds that it was “disputed territory.” Then, days after Bhutan protested the Chinese move,

The Chinese reiteration of its claim to a large chunk of eastern Bhutan could well be a message to India. Though China has claimed areas of northern and western Bhutan since the 1950s, the eastern claim has never been pitched directly till now. The reason is that this claim is linked to Beijing’s demand that India return the Tawang monastery and its surrounding area to China as part of any overall settlement.

China’s signal came through its attempt in early June to get the Global Environment Facility of the UNDP to stop funding activities in Bhutan’s Sakteng sanctuary in eastern Bhutan on grounds that it was “disputed territory.” Then, days after Bhutan protested the Chinese move,  (

( (

( PREV

PREV