-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

China's export of cheap clean energy equipment is a public good as relatively poor countries can now afford large clean energy projects

This article is part of the series Comprehensive Energy Monitor: India and the World

The emergence of China and India as major forces in the global economy is the most significant economic development in the last three decades. The simultaneous emergence of two large economies has led to the perception, at least amongst more casual observers, that China and India are similar. Though China and India started at almost the same level of per-person incomes three decades ago and shared the goal of poverty alleviation through economic growth, their development trajectories and achievements have diverged significantly.

China’s dominance in the solar photovoltaic (PV) value chain must be seen in the context of its dominance in manufacturing.

China’s growth exploded through the industrial sector aided by low-cost manufacturing; India’s growth, in contrast, was fuelled by the rapid expansion of services which was not the traditional development path that begins with low-wage manufacturing. Between 1978 and 1995, manufactured exports rose over 100-fold in China. By 2006, China overtook Japan as the world’s largest manufacturer (in a gross value-added basis) and industry accounted for roughly half of China’s GDP (gross domestic product) from 2005-06. In 2010, China overtook the United States (US) as the world’s largest manufacturer. Industry dominated by manufacturing contributed 40 percent to China’s GDP in 2017 and about 36 percent in 2021. China’s dominance in the solar photovoltaic (PV) value chain must be seen in the context of its dominance in manufacturing.

Though China’s solar energy program was initially designed to meet low-end demand for electricity from rural households, China leveraged its manufacturing capabilities to respond to high-end demand for solar panels from Germany, Spain, and Italy in the 1990s. Provincial and local governments saw the opportunity to generate skilled and semi-skilled jobs by setting up solar manufacturing facilities with funding support for “strategic industries” from the federal government. This expansion led to a dramatic reduction of solar panel and module costs for renewable energy consumers initially in Europe and eventually in other parts of the world including India.

Globally between 1980 and 2012, solar module costs fell by about 97 percent. According to a detailed analysis of factors behind the cost reduction, policies that stimulated market growth accounted for 60 percent of overall cost decline in solar modules and government-funded research and development (R&D) for the remaining 40 percent. R&D in advanced economies was important in the early years but the exponential decrease in cost in the last decade was on account of economies of scale in manufacturing, for which China must be given credit.

Though cost reductions in technologies to harness solar energy has expanded the consumer base for solar energy, the effort was driven less by China’s desire to subsidise the production of global public goods and more by China’s quest to maintain its competitive edge in manufacturing based on cheap labour and abundant capital. China’s 12th five-year plan articulated a green strategy to turn low carbon industries into major drivers of the economy. The Communist Party of China endorsed the strategy of leveraging low carbon development for China’s economic and social development. The development of renewable energy manufacturing capabilities was thus not just a part of China’s environmental and foreign policy (in the context of climate change negotiations) but also a part of its industrial policy. Essentially, China leveraged its industrial policy in its climate policies and not the other way around.

China believed that the global conversation about climate change had moved from “well-intentioned” environmentalism to the future geo-political international economic order and that not investing in low carbon energy sources would affect China’s economic and trading competitiveness.

Behind China’s drive to maintain its competitive edge in manufacturing renewable energy technologies (and other goods) was what Feng refers to as “economic insecurity” that originated primarily from China’s qualitative weakness. China believed that the global conversation about climate change had moved from “well-intentioned” environmentalism to the future geo-political international economic order and that not investing in low carbon energy sources would affect China’s economic and trading competitiveness.

Motivations that turned China into a consumer of renewable energy were different from those that turned China into a producer of renewable energy technologies. Today, China is the world’s largest consumer of renewable energy but in the early stages of the industry, the need to absorb excess capacity particularly of solar modules was the motivation behind domestic consumption. Following the lead from Germany, China introduced an attractive feed-in tariff to promote the domestic use of solar energy in 2013. By 2015, China surpassed Germany as the largest market for solar energy in the world. Domestic consumption of renewable energy (seen as part of its climate change policy) by China is in large part a co-benefit of its industrial strategy.

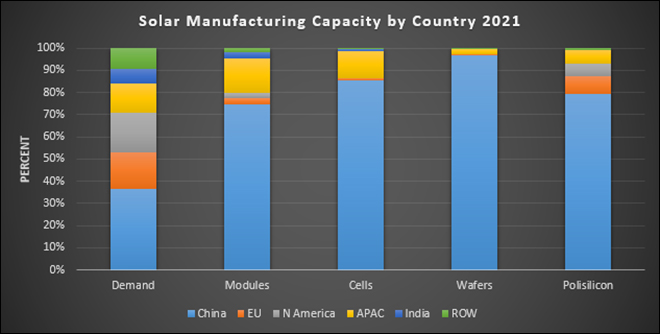

Today, China’s share in all segments of the value chain (polysilicon, ingots, wafers, cells, and modules) is about 80 percent. This is more than double China’s share of global PV demand. In addition, China is home to the world’s top 10 suppliers of solar PV manufacturing equipment. According to the International energy agency (IEA ) the world will almost completely rely on China for the supply of key building blocks for solar panel production through 2025. Based on manufacturing capacity under construction, China’s share of global polysilicon, ingot, and wafer production is expected to reach almost 95 percent.

Trade barriers increase the cost of transitioning to low carbon growth paths and thus go against the spirit of solving a common global problem conveyed in negotiating frameworks of multilateral climate platforms.

China’s suspicion that the real motivation of western powers was in securing economic advantages but masked by powerful ethical discourse in climate dialogues has some merit when seen in the context of renewable energy technology-related trade disputes between countries that include, but are not limited to, China and India. Developing as well as developed countries are building up financial and non-financial trade barriers to protect domestic renewable energy manufacturers. Trade barriers increase the cost of transitioning to low carbon growth paths and thus go against the spirit of solving a common global problem conveyed in negotiating frameworks of multilateral climate platforms. The imposition of carbon-related border adjustment taxes proposed by the United States and Western Europe suggests that green marginalization is indeed a realistic possibility.

The expansion of scientific and technological capabilities in China has created a more multipolar global scientific landscape. In a multipolar scientific landscape, the big challenge is to institute traffic systems between China and the rest of the world to reduce transaction costs with everyone having to play by the same rules. China’s ability to scale clean energy manufacturing dramatically reduced the cost of clean technologies. This cost reduction is a public good from a climate perspective because relatively poor countries can now afford large clean energy projects thanks to the import of cheap clean energy equipment from China.

Source: International Energy Agency; APAC: Asia Pacific, ROW: Rest of the World

Source: International Energy Agency; APAC: Asia Pacific, ROW: Rest of the World

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Akhilesh Sati is a Programme Manager working under ORFs Energy Initiative for more than fifteen years. With Statistics as academic background his core area of ...

Read More +

Ms Powell has been with the ORF Centre for Resources Management for over eight years working on policy issues in Energy and Climate Change. Her ...

Read More +

Vinod Kumar, Assistant Manager, Energy and Climate Change Content Development of the Energy News Monitor Energy and Climate Change. Member of the Energy News Monitor production ...

Read More +