-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

A story published in the Financial Times on 19 February revealed China’s strategy of adopting Pakistan’s state policy of wooing “good” terrorists for its intended self-gains. The story exposed China’s clandestine talks with Baloch militants for “more than five years to protect the $60 billion worth of infrastructure projects it is financing as part of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC)” and have made “a lot of progress by not making a forceful push.”

Covert romancing with terrorists is not new to China, especially in the Af-Pak region. China’s appeasement policy towards terrorists has a long history, starting with the “Baren incident” in the restive Xinjiang province that took place between Uyghur militants and Chinese government forces in April 1990. The Baren incident was the outcome of militants who participated in proxy war for Afghanistan against Soviets and Islamists trained in the Af-Pak region.

According to Chinese officials, Uyghur militants used automated weapons against Chinese security forces throughout the Baren town. The uprising lasted for several weeks in which 23 were killed and 232 got injured. But, according to other sources and indigenous population whom the author met in 2013 as part of his PhD research, more than 1,600 people were killed in the incident. After the incident, China tackled the Xinjiang problem with an iron fist, arrested more than 10,000 Uyghurs, put a control on religious activities and started “ethnic cleansing” through mass migration of Hans from other parts of China. China’s internal actions to curb the uprising in Xinjiang created global uproar for mass human rights violations. Externally, besides strategic reasons, China also started its romanticism with terrorists in Afghanistan and Pakistan to make Xinjiang secure from centrifugal tendencies and terrorist activities.

The romance started in the late 1990s, when China held talks with Taliban for the shutdown of Uyghur training camps in Afghanistan. The Taliban representatives gave assurances from time to time. However, the year 1997 once again saw the reinforcement of ethnic separatism and “Islamic fundamentalism” in Xinjiang. In February 1997, Kulja in northwest Xinjiang became the centre of violence between Uyghur militants and Chinese forces, in which, according to official Chinese account, more than 120 people died and thousands got injured. Uyghur sources, on the other hand, claim that this wave of violence resulted in the killing of more than 400 natives. Internally, once again, China gave immense powers to security forces and started its “strike hard campaign” to curb terrorism, separatism and extremism in the province. Chinese authorities in Xinjiang arrested 2,773 terror suspects and seized 6,000 pounds of explosives and 31,000 rounds of ammunition.

After 1997, China adopted an external policy to reinforce and help authoritative regimes of Central Asia for curbing all Uyghur activities in their countries and also started a fresh round of high-level talks with the Taliban. In November 2000, Chinese ambassador to Pakistan held talks with Taliban leader Mullah Mohammad Omer. This was the first time when a senior diplomat of any non-Muslim country had a meeting Mullah Omer. Mullah Omer promised that Taliban will not allow Uyghurs to launch attacks in Xinjiang against the interests of China, with the condition that they will continue to remain in the Talibani ranks.

After 9/11 attacks, the United States dethroned Taliban from Afghanistan. The Chinese state maintained their relations with Quetta Shura, the Taliban leadership council based across the border in Pakistan for security and peace in their sensitive and strategic Muslim-dominated region of Xinjiang. There are reports that China openly provided arms and ammunition to the Taliban as the US military presence in Afghanistan made it feel encircled by the Americans to an extent even greater than was the case before the Afghan war.

China’s real concerns in Afghanistan are not peace or reconciliation, but its internal security threat in Xinjiang and other strategic reasons like India-US relations.

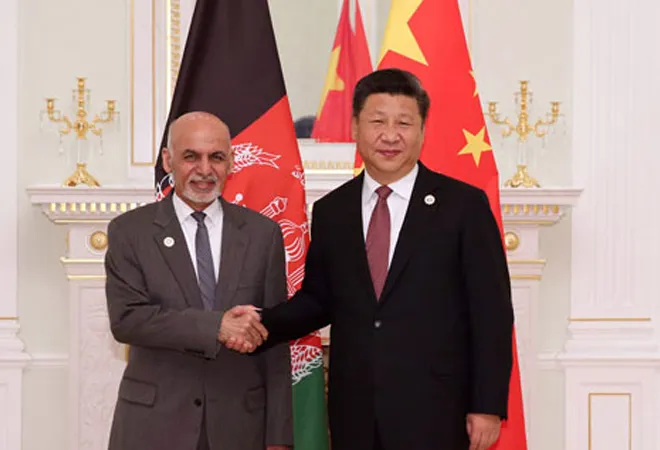

In December 2017, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi pitched for talks between the Afghan government and Taliban at a trilateral meeting between foreign ministers from Pakistan, Afghanistan and China in Beijing, which is against the Indo-US interests and also against the stated position of the Afghan government on this issue. Therefore, it is easy to also see the real intention behind the Chinese strategy of inviting Afghanistan to become part of the CPEC.

Towards the terror groups in Pakistan, China used same strategy as in Afghanistan, but the reasons are much broader, more strategic and motivated by strong economic and political undercurrents. China was the only country among the 15-member United Nations Security Council (UNSC) that blocked India’s bid to designate Masood Azar, the chief of Jaish-e-Mohammad, as a global terrorist in November 2017. China has kept its “technical hold” on the ban of Masood Azhar even after President Xi Jinping started his second term in office. The factors that shaped the policy of China to romance terrorists in Pakistan, which is further reinforced by its repeated technical hold on Masood Azar, are intended to create a trust-worthy impression of China among terror outfits in Pakistan. But here, the factors are much more complicated than in Afghanistan.

The first reason is to secure the $60 billion worth of Chinese investment and its human resources working on the multitude of CPEC projects, as a sizeable part of the CPEC runs through the disputed area of Pakistan occupied Kashmir (PoK). The CPEC is exposed to direct threats from the terror groups which have found safe haven in the illegally occupied areas as also from Indian security forces in case of any escalation of conflict between India and Pakistan.

After the appeasement of terrorists like Masood Azar, the Chinese have sent more manpower to work on CPEC projects in these disputed areas known as the “launch pads” of terrorists against India.

The number of Chinese living in Pakistan in 2017 has reached 30,000 to 40,000 against 10,000 in 2009. More than 15,000 to 20,000 Chinese are directly working on CPEC projects. Though Pakistan has promised to provide security to CPEC projects and the Chinese workers, the decrease in the number of attacks and killings of Chinese workers is actually thanks to the Chinese outreach to terror groups and political support extended to Masood Azhar at the global level. How else, is it possible that in 2017 only two Chinese workers were killed in the terror sanctuaries of Pakistan in Quetta? These killing were not done by any of the terror organisations in the Af-Pak region with whom China had political understanding, but by the terrorists of the Islamic State (IS). Such is the confidence of the Chinese following its romance with the terrorists, that the Chinese ambassador to Islamabad was quoted by the Dawn News that “terrorists are no longer a threat to the economic corridor”.

Furthermore, China views attacks on India by terror groups based in Pakistan as a convenient counter to the growing India-US bonhomie.

As China suspects India as an ally in the US efforts to contain China in the Asian and the global theatre, especially after MOU of Logistics Exchange Memorandum of Agreement (LEMOA) between the US and India on 29 August 2016, they have found appeasement of the terror networks as a good countermeasure against India.

The other reason to appease the terror groups in Pakistan is to stop the secessionist and centrifugal tendencies in restive Xinjiang, as more and more Uyghurs and Pakistanis travel across the Karakorum highway for trade and other activities. Uyghur militants in the past were trained and radicalised in Pakistan by its home-grown terror groups. Tacit support to terror organisations in the international arena has helped China to stop the radicalisation of Uyghurs in Xinjiang by Pakistani terrorists.

For global peace and prosperity, China should keep its promise on terrorism. It is a member of all the international and regional forums and has criticised terrorism, extremism and separatism as the three evils. As a member of BRICS and the founder-nation of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO), China should live up to the pledge of these forums to fight terrorism. The SCO’s first charter signed in Shanghai Convention was on “combating terrorism, separatism and extremism”. The same was highlighted in BRICS summit at Xiamen, China, where the summit declaration asserted that those responsible for committing, organising or supporting terror acts must be held accountable. This summit declaration had named almost all the global terror organisations.

The SCO’s first charter signed in Shanghai Convention was on “combating terrorism, separatism and extremism”.

However, question remains when will China stop its tango with terrorists. China walking the talk on its anti-terror commitments is an absolute must for global and regional peace and also a pre-condition for betterment of India-China relations.

Ayjaz Wani is Research Fellow at ORF Mumbai

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Ayjaz Wani (Phd) is a Fellow in the Strategic Studies Programme at ORF. Based out of Mumbai, he tracks China’s relations with Central Asia, Pakistan and ...

Read More +