Recent reports and satellite imagery show that the Chinese have constructed a new village inside two kilometres of Bhutanese territory. The village lies on the eastern periphery of the disputed Doklam plateau where, in 2017, India and China were involved in a standoff.

The present 470-km-long boundary between Bhutan and China isn’t demarcated and over 25 percent of this border has been disputed for decades. The disputed regions in the northern sectors include 495 sq kms of the Jakurlung and Pasamlung valley in the Wangdue Phodrang district. The other disputed regions include the 269 sq kms of Doklam, Sinchulung, Dramana and Shakhatoe in the Samste, Haa and Paro districts of the northwestern part of Bhutan. The Chinese claim on these areas of Bhutan has been totally dependent on Tibet’s claim and, hence, it is important to understand the historical relations between Tibet and Bhutan to understand the present border dispute between China and Bhutan.

In the early 8th century, when Tibet was a military power, it invaded Bhutan. Lamas settled down in the southern valleys (earlier name of Bhutan when it wasn’t unified and it was just located to the south of Tibet) and intermarried with the local people. In the 9th century, even though Tibetan forces withdrew from Bhutan, the Lamas frequently used to visit Bhutan where they exercised spiritual and temporal authority. It was in the middle of the 17th century that Ngawang Namgyal, a refugee forced out by Tibetan rulers, unified Bhutan.

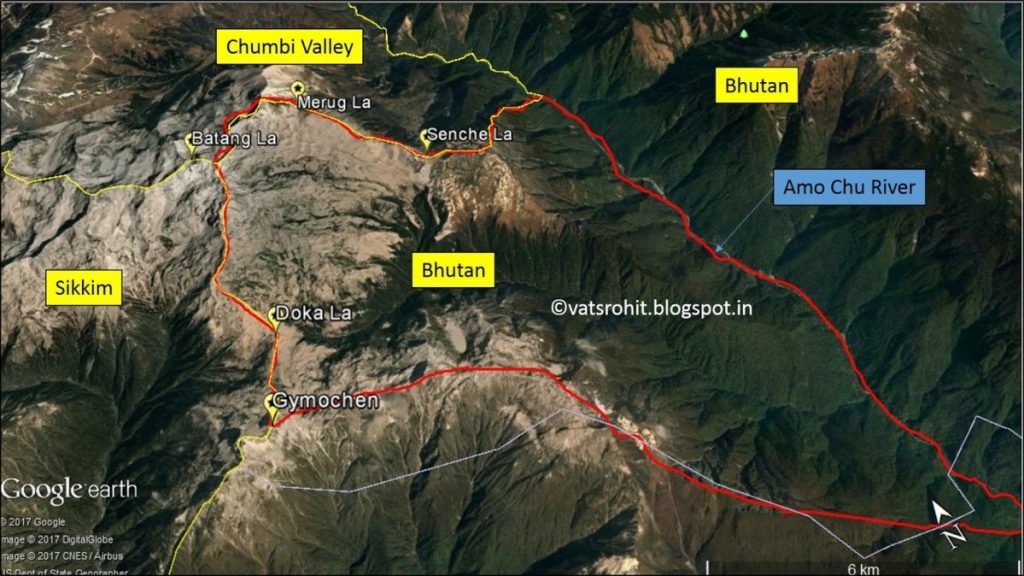

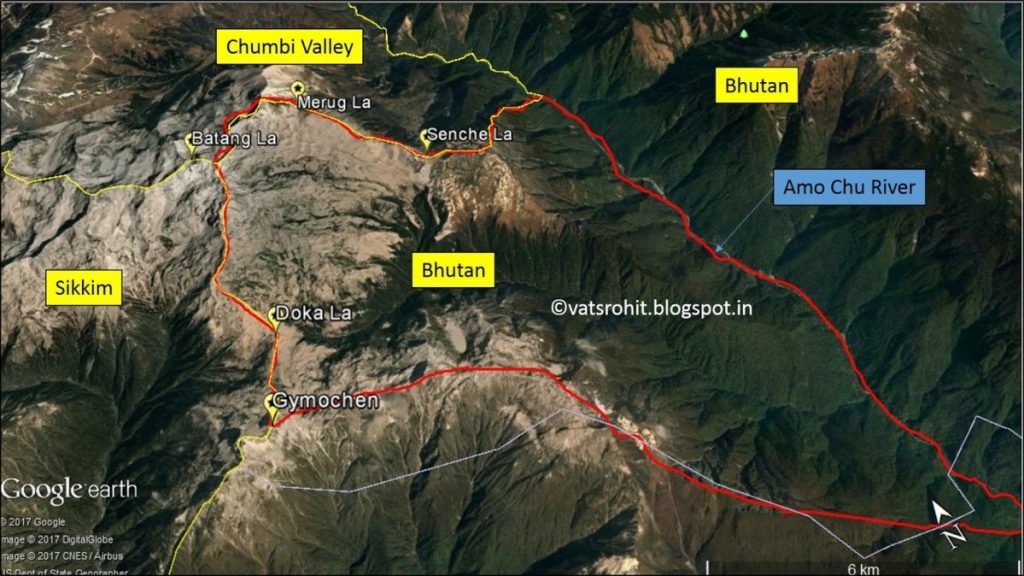

The trijunction will be at Batung La and the border of Bhutan will run along the northern ridge of Doklam and hold the critical Jampheri ridge.

In the early 19th century, the British Raj in India was looking for ways to trade with Tibet. After losing the Anglo-Bhutan war over Cooch Behar, Bhutan was forced to arrange the first British trip to Tibet. The Tibetans, on hearing of the planned expedition, set up a military outpost in Chumbi valley, which the British cleared easily. The British realised the weakness of the Qing dynasty and made Sikkim’s and Tibet's overlords settle the boundary at Doklam plateau through the Anglo-Chinese convention of 1890. Bhutan, which was an important part of the trilateral junction, was allowed to enter this treaty only after 20 years.

The problem at the Doklam plateau started with the treaty, where the boundary of Sikkim and Tibet wasn’t clearly mentioned. It stated that the boundary between Sikkim and Tibet shall be “the crest of the mountain range separating the waters flowing into Sikkim Teesta and its tributaries from the water flowing into the Tibetan Mochu and northwards into other Rivers of Tibet.”

With the interpretation of the treaty, China claims the borderline begins at Mount Gipmochi and the border includes the entire Doklam area within the Chumbi valley ending at the Jampheri ridge on the south and the joining point of the Doklam river on the east. However, modern cartographic studies show, through the principle of watershed, that the actual crest of the mountain range is Merung La (15,266 ft) compared to Gipmochi (14,518 ft). Hence, the trijunction will be at Batung La and the border of Bhutan will run along the northern ridge of Doklam and hold the critical Jampheri ridge.

Doklam plateau | Source: Google Earth

Doklam plateau | Source: Google Earth

The Chinese have often claimed the areas and it was Mao’s five finger policy that claimed this area of Bhutan for the Chinese. China has also been aggressive in pushing its claims on the northern side of the border by sending grazing parties and constructing military patrols inside the Bhutanese border. China has published maps that showed the Doklam plateau and parts of the northern sectors of Bhutan under its control.

The Chinese have often claimed the areas and it was Mao’s five finger policy that claimed this area of Bhutan for the Chinese.

The trajectory of the boundary negotiations between China and Bhutan can be divided into three phases. The first phase is the engagement phase that started in 1984 with holding formal boundary talks and discussing issues of mutual concern for both countries. The border between China and Bhutan till the late seventies was considered an extended part of the Sino-Indian border dispute and Bhutan had formally not engaged with China.

The second phase is the redistribution phase when a package deal was offered to Bhutan in 1996. China offered to cede 495 sq km of territory in the remote, uninhabited and glaciated area of the Jakarlung and Pasamlung valley of the northern sector in return for the strategic locations of Sinchulung and Shakhatoe in the Doklam plateau. The area could provide additional security to the narrow Chumbi valley and it overlooks the Siliguri corridor, which is strategic as it connects India’s northeastern states to the rest of the country. The package deal didn’t work out as Bhutan rejected the deal at India’s behest. Two years later, in 1998, China and Bhutan signed a peace agreement and promised to “maintain peace and tranquility on the Bhutan-China border areas.” The agreement was significant as it recognised Bhutan as an independent sovereign state for the first time.

The third and final phase is the normalisation phase, where multiple border talks have been held between the two countries and where China put pressure on Bhutan to cede Kula Kangri, the highest mountain peak in Bhutan. The Chinese government has promised Bhutan economic engagement and, over the last few years, China has started exporting telecommunication and farming products, but the border talks have not moved beyond a point.

There have been 24 boundary talks, but the talks between the two nations came to an abrupt halt post the 2017 Doklam standoff.

In 2017, the Indian Armed Forces and People’s Liberation Army (PLA) engaged in a military standoff in Doklam near the trijunction border area of Donglang. The Chinese were found to be constructing roads in the disputed territory of Doklam. Recently, at the Global Environment Facility (GEF) meeting in June, China objected to granting funds for projects in the Sakteng wildlife sanctuary in the eastern section of Bhutan citing that the area was disputed territory.

This is the first time China has claimed the area, which s about 740 sq km, and it had never featured in any of the boundary talks. There have been 24 boundary talks, but the talks between the two nations came to an abrupt halt post the 2017 Doklam standoff. The recent claim by China to an area clxsose to Tawang in Arunachal Pradesh (which China claims as South Tibet) might be a tactic to pressurise the Indian government to settle the Doklam crisis and bring Bhutan for negotiations.

The author is a research intern at ORF.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Doklam plateau | Source: Google Earth

Doklam plateau | Source: Google Earth PREV

PREV