The terrorist attack on Mumbai on 26 November 2008 exposed key vulnerabilities and highlighted inadequate tactical and operational aspects of the Indian security response. Episodic reforms followed in the country’s security apparatus, but went back to default mode in less than a decade. This failing was evident in India’s uncoordinated and chaotic response to the terrorist attack on the Pathankot Air Force base in January 2016 that once again, painfully underscored issues of tasking, synergy and jointness, in counter-terrorism (CT) capabilities.

There is a need to re-evaluate old doctrines that have thus far determined the use of intervention forces in domestic counter-terrorism situations and the way the Indian security establishment pre-positions advanced components of special units in a cohesive network covering all of India.

Following the 26/11 attack, a number of structural reforms were ambitiously proposed for the security set-up — notably, the creation of regional hubs for National Security Guard deployment in various states, the establishment of the National Investigation Agency (NIA), the setting up of a National Intelligence Grid (NatGrid), and the plan for a National Counter Terrorism Centre (NCTC) — along with several other initiatives, to enable a qualitative improvement in our counter-terror infrastructure and strategy. <1>

There is a need to re-evaluate old doctrines that have thus far determined the use of intervention forces in domestic counter-terrorism situations and the way the Indian security establishment pre-positions advanced components of special units in a cohesive network covering all of India.

The National Counter Terrorism Centre (NCTC), was to be founded to bring a multitude of agencies under a unified command. The NCTC would have been responsible for preventing terrorist attacks, containing them in the event they were launched, and guiding a response in the aftermath. A decade since 26/11, the proposal to create this unified command and control structure for counter terrorism responses is still just a piece of paper. The NCTC was supposed to be aided by the National Intelligence Grid (NATGRID), which is supposedly networked to the databases of 21 different agencies that contain vital information and intelligence. Previously, each organisation has its own stand-alone database that cannot be accessed by others.

The attack however, was not a failure of intelligence gathering, with reports indicating 26 warnings were passed by Indian intelligence agencies to the Mumbai police between 2006 and 2008 about a possible attack. New mechanisms like Multi Agency Centres (MAC) and Subsidiary Multi Agency Centres (SMAC), to enable intelligence sharing and coordination amongst multiple agencies continue to remain deficient lacking high level coordination which involves the Home and Police departments working together with their central counterparts. <2> This is unlikely to come through an administrative fiat, and would need to be subject to legislation.

Complicating matters further, India’s police and internal security system is highly disjointed and poorly coordinated. India’s federal political system leaves most policing responsibilities to states. State police forces have perennially suffered from inadequate counter-terrorism training and equipment. <3> To be effective in containing a terrorist incident, first responders need to have plenty of both to neutralise or contain the threat. It is important to note that the majority of deaths in the 2008 attacks occurred in the first hour, followed by a tense drawn-out period of four days when attackers barricaded themselves into buildings, taking hostages with them. The attack graphically illustrated how ill trained and equipped the local police was to handle a major terrorist incident in 2008. Many police officers remained passive, seemingly because they were outgunned by the terrorists. In the ensuing years, the Mumbai police has raised a commando force going by the moniker “Force One”. However, reliance upon a police tactical team even in those jurisdictions where police are armed can only be effective if that capability can respond to multiple threats within a very short time.

As a first step, even a marginally improved quality of basic training, would have a broader effect of increasing the response capacity of India’s police forces.

If another attack dispersed and highly mobile like in Mumbai or more recently, as in the Paris attacks of 2015, where multiple teams attacked several locations at once — combining armed assaults, carjackings, drive-by shootings, prefabricated IEDs and hostage situations — it is doubtful that state police forces would be able to adequately respond in time or in effect even today, a decade after 26/11. As a first step, even a marginally improved quality of basic training, would have a broader effect of increasing the response capacity of India’s police forces.

In 2008, the National Security Guard (NSG) was headquartered in south of Delhi and lacked bases anywhere else in the country. Worse, it had no aircraft of its own and could count on dedicated access to Indian Air Force aircraft in an emergency. Any rapid-reaction force must reach the scene of a terrorist incident as soon as possible, and no later than 30–60 minutes after it has commenced. In Mumbai, nearly 10 hours elapsed. The NSG was further hampered by an absence of relevant equipment such as night vision goggles, poor intelligence and planning such as the lack of an operational command centre.

Since 26/11, governments have implemented knee jerk reforms drawn from the NSG’s failure to reach Mumbai quickly, by establishing hubs in Mumbai, Kolkata, Bangalore, Chennai, Hyderabad and more recently Ahmedabad, each with about 250 personnel. However, questions about the quality of the NSG as a force remains, as it expands. <4> In Pathankot, reports indicate none of the terrorists were shot by members of this ‘elite’ force. On the contrary, they lost an officer of the rank of Lt. Colonel who broke standard operating procedures for dealing with improvised explosive devices and lost his life.

Since 26/11, governments have implemented knee jerk reforms drawn from the NSG’s failure to reach Mumbai quickly, by establishing hubs in Mumbai, Kolkata, Bangalore, Chennai, Hyderabad and more recently Ahmedabad, each with about 250 personnel. However, questions about the quality of the NSG as a force remains, as it expands.

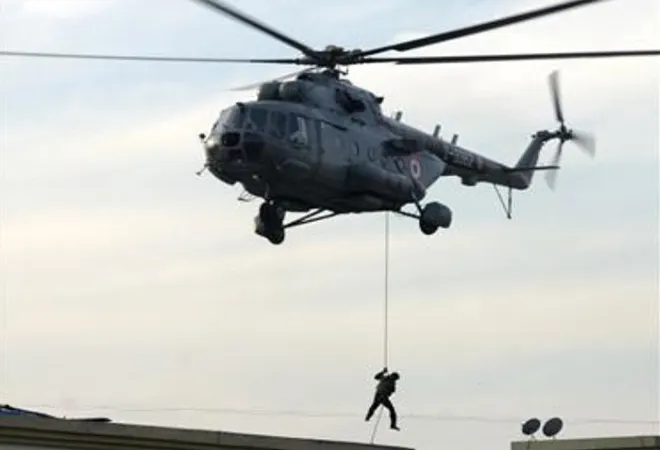

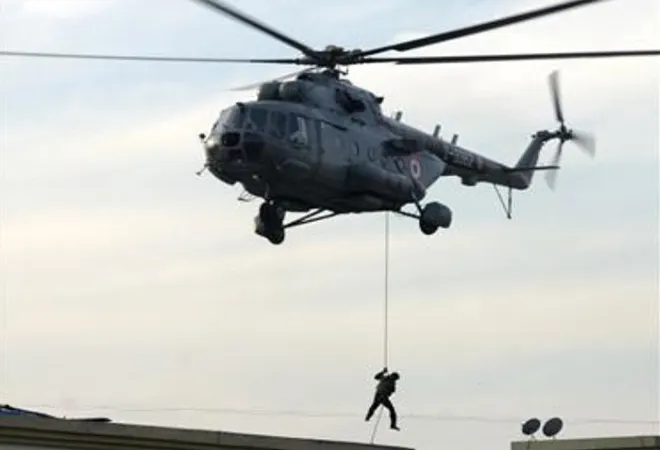

The undeliberated expansion of the NSG has resulted in falling standards of training and manpower, which has, in turn, weakened key capabilities. <5> Hubs have been created, but the question of dedicated aircraft is still unanswered. The NSG requires tactical helicopters for timely movement, but this has not even been raised as a policy option. <6> Its night combat capability is also inadequate — long-range night vision devices and hand-held thermal imagers are still unavailable. The world over, special operations units like the SAS (UK), GSG-9 (Germany), GIGN (France), all number between 200 and 400 personnel and work out of centralised locations. <7> Most special forces assigned CT roles, are equipped or permanently assigned their own air assets. The British SAS has specially trained and equipped pilots and helicopters at its disposal, and its personnel train extensively with these helicopters. <8> In the United States, the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s has its own helicopter unit to for critical interventions. In India’s case an ambitious Rs 1,400-crore modernisation plan continues to languish on paper.

The nature of terrorism has changed significantly over the years. Dispersed “maximum violence” attacks, like those in Mumbai, and in Paris are the new norm, and require rapid intervention. But, ten years on from 26/11, the NSG continues to face serious logistical and transportation challenges. Simply put, the NSG cannot wait around to execute a planned counter-assault. Time is a luxury that doesn't exist under most modern terror scenarios. In terms of personnel, no matter how well equipped or trained specialist forces like the NSG are, responding to any terrorist attack requires the development of a strong, police-led capability. Under such an arrangement, first responders are always local, armed police officers. The deployment of specialist counter terrorism forces can only be considered an option in the event of failure. Developing interoperability between specialist CT assets and police forces by way of regular training and exercises will address some of the existing inter-agency co-operation gap.

Any CT responses in India needs to start from processing intelligence alerts, mobilising first responders, carrying out counter terror operations under a well-defined command-and-control system. Pre-positioning the advanced components of special units in a network covering all of India and using aviation based platforms as an enabler hold potential in addressing some of the NSG’s short comings. Policymakers will also need to consider the introduction of new technologies in the context of counter-terrorism and intelligence collection, in the capability assessment and procurement process. In the end, improvement in India’s CT capability will require significant infusions of resources, policy consistency, and political will in the coming year if it wants to effectively prevent another significant terrorist attack.

<1> C. Christine Fair, Prospects for Effective Internal Security Reforms in India, Commonwealth & Comparative Politics (July 2011) pp 145-170.

<2> Paul Staniland, “Improving India’s Counterterrorism Policy after Mumbai”, CTC Sentinel, Vol. 2 issue 4 (April 2009). (accessed on 25 October 2018).

<3> Angel Rabasa, Robert D. Blackwill, Peter Chalk, Kim Cragin, C. Christine Fair, Brian A. Jackson, Brian Michael Jenkins, Seth G. Jones, Nathaniel Shestak, and Ashley J. Tellis, "The Lessons of Mumbai", Rand Corporation, OP 249 (2009). (accessed on 24 October 2018)

<4> Gujarat gets new NSG hub; fifth in the country, The Economic Times, 14 July 2018. (accessed on 21 October 2018)

<5> Saikat Datta, Revisiting the NSG operations: what worked and what didn't, Hindustan Times, 25 November 2014. (accessed on 22 October 2018)

<6> Jugal R. Purohit, No choppers, no training, no men: National Security Guard in crisis as helicopter and manpower shortages cripple counter-terror effort, 18 April 2013. (accessed on 22 October 2018)

<7> Rajit Ojha, “Force Alarm”, The Caravan , 1 February 2016 (accessed on 25 October 2018)

<8> Tyler Rogoway, About That "Blue Thunder" Counter-Terror Chopper That Landed On London Bridge, The Drive, 4 June 2017. (accessed on 22 October 2018)

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV