-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

At a time when multilateralism is facing a crisis of existence, what is the significance of a day that advocates for gender equality in multilateralism?

Image Source: Getty

Multilateralism, as we know it, is over a hundred years old—its advent can be traced back to the League of Nations, created in Geneva in 1919. It took over a century for multilateralism to formally acknowledge the role of women in global governance with the adoption of the International Day of Women in Multilateralism in 2021 by UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation), which is marked every year on 25 January. It advocates for an increased representation of women in key decision-making positions in the multilateral system, ensuring that multilateralism works for women and girls through gender transformative actions and agreements.

It advocates for an increased representation of women in key decision-making positions in the multilateral system, ensuring that multilateralism works for women and girls through gender transformative actions and agreements.

At a time when multilateralism is being severely challenged from all quarters, amidst the rise in global uncertainties, the backlash against globalisation, an overwhelming lack of trust in multilateral institutions, and the looming United States (US) withdrawal from them, is there any significance to having a day that advocates for gender equality in multilateralism? The answer to that would be an unequivocal yes—the multilateral system, which has delivered global agreements, treaties and conventions on gender equality, is essential for making meaningful progress in eliminating gender inequality. Equally, the beleaguered multilateral system needs more participation, engagement and decision-making by women, not only to promote inclusiveness, but to effectively respond to contemporary challenges of climate, sustainable development, peace, security, and human rights.

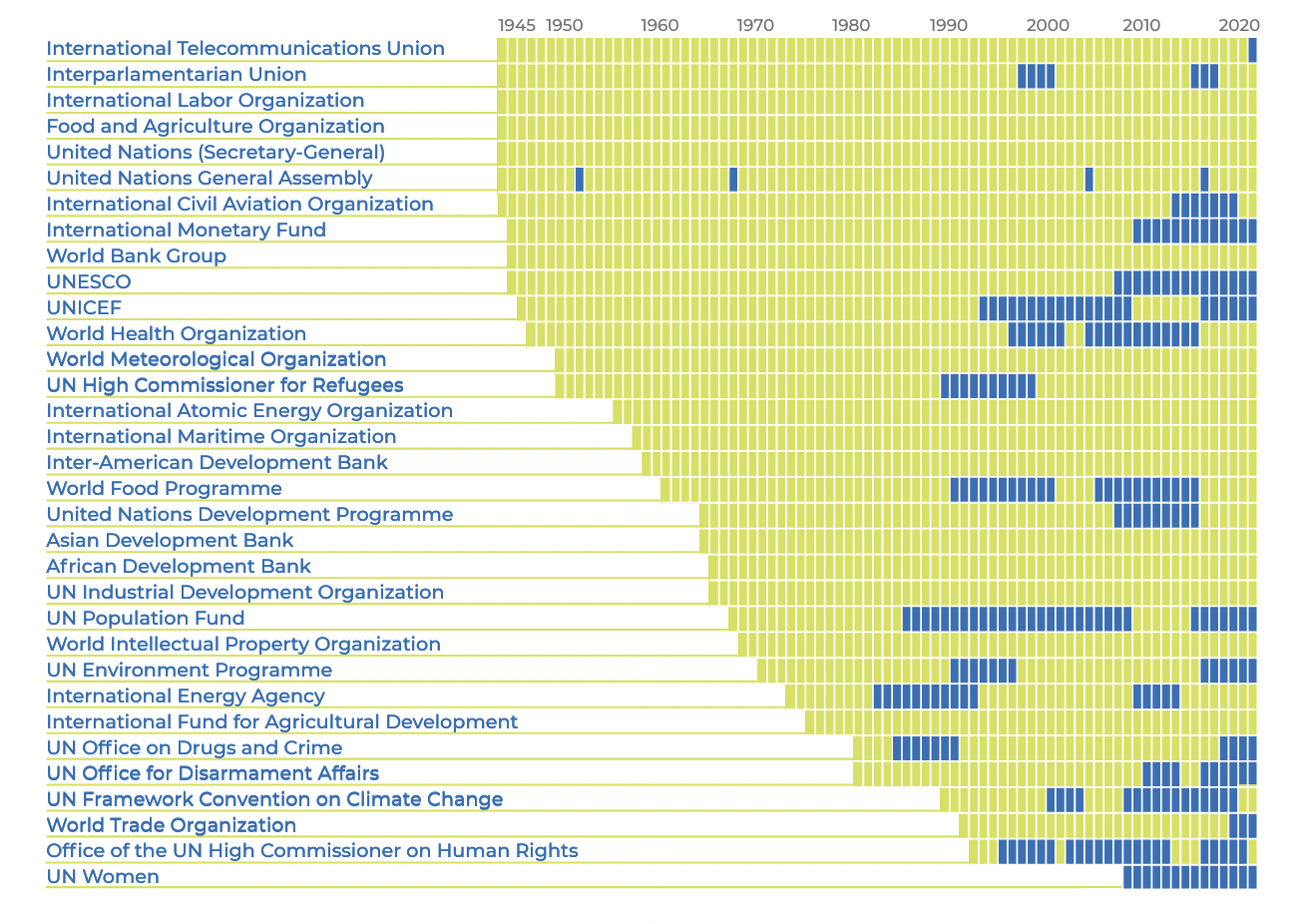

Global governance and decision-making are heavily dominated by men. According to a 2023 report by GWL Voices, an organisation dedicated to promoting a gender-equal international system, there is a striking scarcity of women in international organisations. Out of the leaders of 33 of the world’s largest multilateral organisations since 1945, women have been in charge for only 12 percent of the time (see figure). It further showed that 13 of these organisations, including all four of the world’s largest development banks, have never elected a woman leader.

Figure: Heads of major multilateral organisations since 1945, segregated by gender

Source: GWL Voices, Annual Report 2023

Women are underrepresented in most positions of power and decision-making. Only 22 percent of the permanent representatives of member states in the UN Security Council were women, between 2015 and 2023. Though conflicts around the world continue to rise, women’s participation in peace processes has been decreasing. Women represented 16 percent of negotiators in UN-led or co-led peace processes, a decline from 23 percent in 2020 and 19 percent in 2021. This is despite the evidence that women and girls are disproportionately impacted by conflicts, and women’s participation in peace processes leads to better results, with higher chances of conclusions being reached in peace talks and a higher likelihood for the implementation and durability of peace agreements.

Women’s participation in the multilateral trading system has also been notoriously low. The call for international trade policies to be gender-sensitive, given the impact of trade on households and individuals, has only recently gained traction.

The discussion on women in multilateralism is linked most often with the discussion on Feminist Foreign Policy. In the ten years since Sweden became the first country to adopt a Feminist Foreign Policy (which it revoked in 2022), it has spread around the world—16 countries have either published an FFP or announced their intention to develop a feminist foreign policy.

FPP represents an opportunity to broaden the discourse and bring in a more inclusive approach to respond to current challenges like the climate crisis, conflict, and inequality.

A report by the International Peace Institute shows that the impact of FFPs in multilateral systems has, so far, not been significant. Even though 3 out of 7 G7 countries, Canada, France and Germany have a FFP, its impact on G7 outcomes has been limited. The report recommends that for FFPs to effectively transform multilateralism, it must be seen as a way to improve an outdated and inequitable system, and not just as a “women’s issue”. At its very best, FPP represents an opportunity to broaden the discourse and bring in a more inclusive approach to respond to current challenges like the climate crisis, conflict, and inequality.

With the ongoing shift in global power from north to south, India has been at the forefront of demanding reforms in the existing multilateral order. The conversation on feminist foreign policy in the Global South has been broader and more intersectional in its scope compared to the Global North. It calls for a decolonised approach to foreign policy, by including countries and communities which have been left out of the multilateral system. This was evident during India’s G20 presidency in 2023, when it advocated for the inclusion of countries from the Global South, including the African Union, as a permanent member. At the same time, it prioritised gender-based policymaking with the concept of women-led-development as a means for women to drive economic, social, and political progress. Multilateralism will need these ideas to survive the century.

At the Summit of the Future which was held last year in a bid to revive multilateralism, a commitment was made to “build a multilateral system that delivers for everyone, everywhere.” Ensuring the full participation of women and their leadership in decision-making in the multilateral order is just the beginning.

Sunaina Kumar is a Senior Fellow at the Observer Research Foundation

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Sunaina Kumar is Director and Senior Fellow at the Centre for New Economic Diplomacy at the Observer Research Foundation. She previously served as Executive Director ...

Read More +