This article is part of the series — Raisina Files 2021.

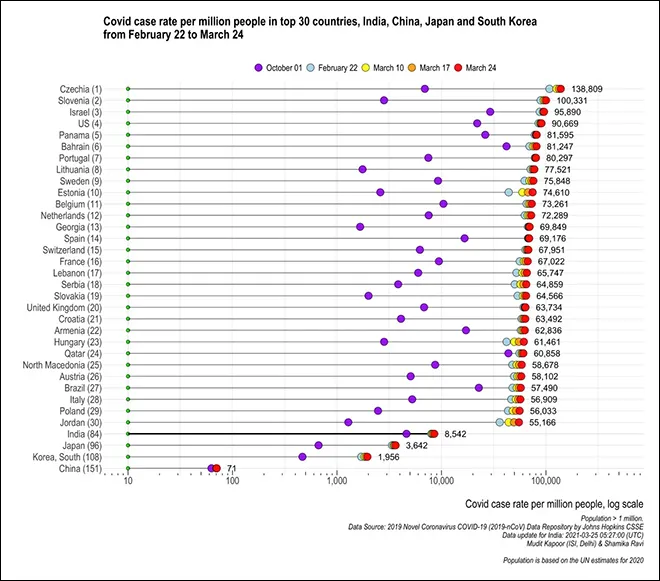

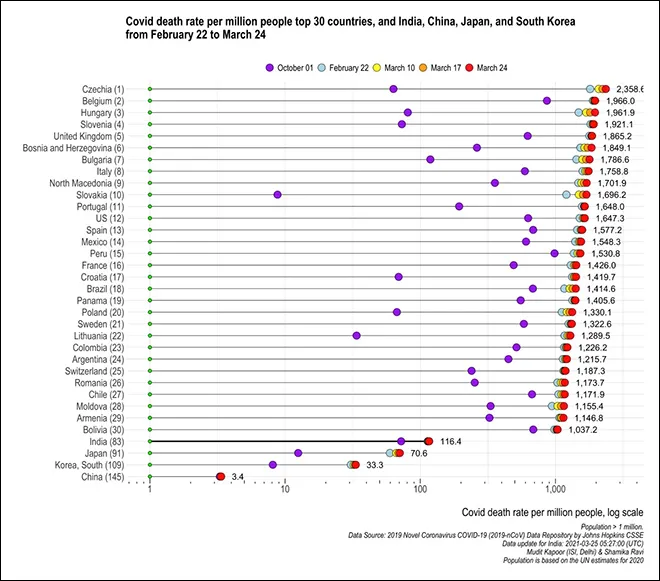

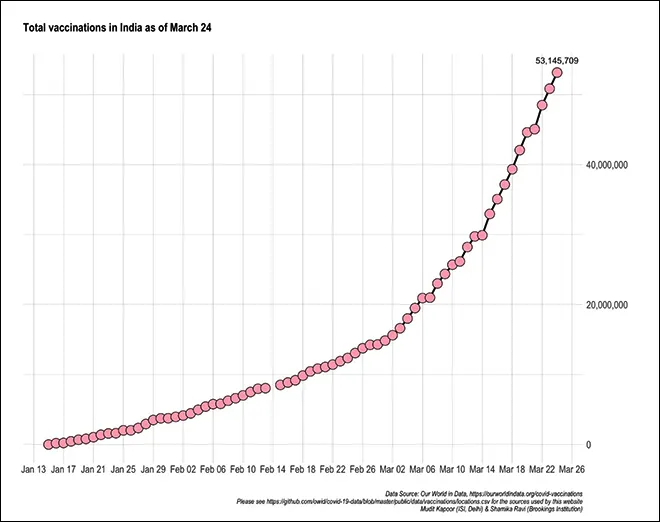

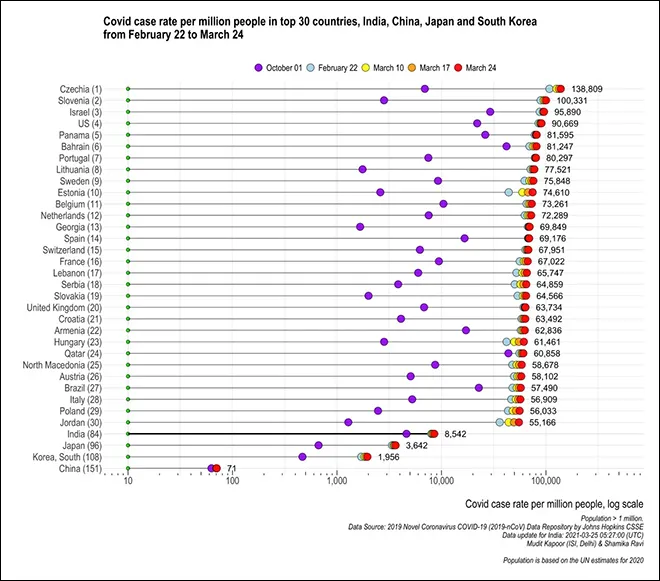

The COVID-19 pandemic is undoubtedly the worst global health disaster of the twenty-first century. It has ravaged economies, destroyed livelihoods, devastated families and curtailed civil liberties in many parts of the world. But not all countries have been affected equally. Rich countries, such as the US and those in Europe, suffered a higher number of cases (see Figure 1) and casualties (see Figure 2), necessitating a larger response from the developed world in the search for a vaccine.

The Spanish flu struck during the First World War when press freedom was severely curtailed in most parts of the world, but in Spain, which was neutral during the war, the press could freely report on cases and fatalities, ultimately giving the pandemic its name.

This is not the first global pandemic to destroy lives and nations. For instance, the Spanish flu in the early twentieth century, when medical science was not as advanced as in recent times, was far more lethal. Importantly, the Spanish flu struck during the First World War when press freedom was severely curtailed in most parts of the world, but in Spain, which was neutral during the war, the press could freely report on cases and fatalities, ultimately giving the pandemic its name. COVID-19 has not been subjected to such restrictions and therefore captured the attention of political leaders worldwide from the early stages of the outbreak. Governments responded by locking down countries and imposing other restrictions, but the only permanent solution to the pandemic was the discovery of a vaccine.

Figure 1: COVID Case Rate Per Million Population, as of 24 March 2021

Source: 2019 Novel Coronavirus COVID-19 (2019-nCoV) Data Repository by Johns Hopkins CSSE Data update for India: 2021-03-25 05:27:00 (UTC); Population is based on UN estimates for 2020.

Source: 2019 Novel Coronavirus COVID-19 (2019-nCoV) Data Repository by Johns Hopkins CSSE Data update for India: 2021-03-25 05:27:00 (UTC); Population is based on UN estimates for 2020.

Figure 2: COVID Death Rate Per Million Population, as of 24 March 2021

Source: 2019 Novel Coronavirus COVID-19 (2019-nCoV) Data Repository by Johns Hopkins CSSE Data update for India: 2021-03-25 05:27:00 (UTC); Population is based on UN estimates for 2020.

Source: 2019 Novel Coronavirus COVID-19 (2019-nCoV) Data Repository by Johns Hopkins CSSE Data update for India: 2021-03-25 05:27:00 (UTC); Population is based on UN estimates for 2020.

Typically, vaccines can take years to be developed and go through clinical trials before being released for public use. But the COVID-19 vaccine was developed and released in less than a year since the outbreak was declared a pandemic. The World Health Organisation (WHO) issued an emergency use listing (ELU) for the Pfizer–BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine on 31 December 2020 and granted ELUs to two versions of the Oxford–AstraZeneca vaccine manufactured by the Serum Institute of India (SII) and SKBio on 15 February 2021. Currently, 82 vaccine candidates are under clinical development and 182 vaccine candidates are in the pre-clinical development phase, a remarkable achievement in global public health.

Race for vaccines

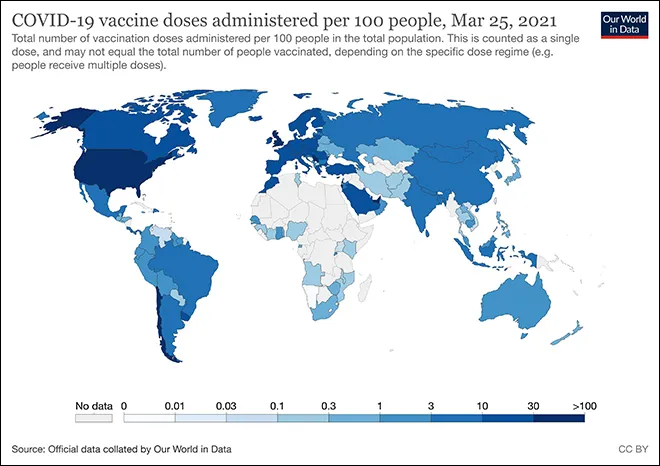

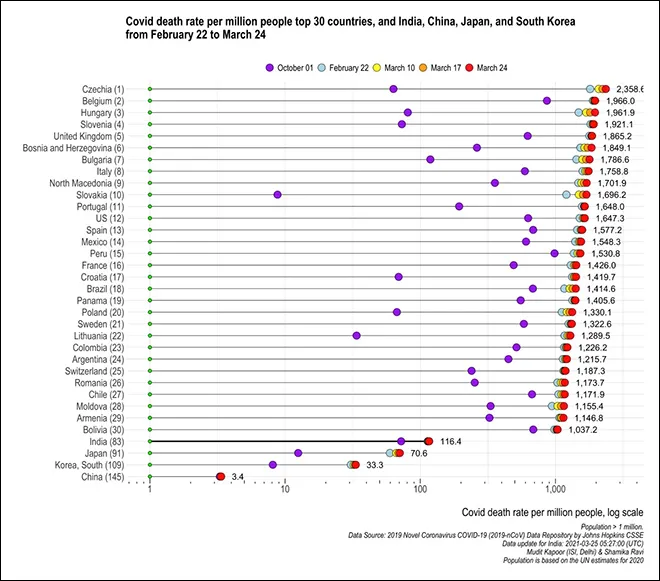

With the discovery of the vaccine, COVID-19 has ceased to be a global humanitarian issue and has metamorphosed into a traditional political economy problem of inequality in access between the rich and the poor countries. In several countries, this has also emerged as a problem of unequal access across regions and demographics. Globally, the number of vaccine doses administered per 100 people is 6.5 (as of 25 March 2021), but there are significant variations across countries and continents. Israel has achieved 115 doses per 100 people, while the US has administered over 35 doses per 100 people and the European Union has achieved 15 doses per 100 people. Meanwhile Asian countries have achieved a modest 4.5 doses per 100 people, mostly on the back of India and China’s significant manufacturing capacities. For most African countries, however, there is either no data available or they have yet to achieve even a single dose per 100 people (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Vaccine Doses Per 100 Population

Source: Official data collated by Our World in Data, accessed on 25 March 2021.

Source: Official data collated by Our World in Data, accessed on 25 March 2021.

The rich countries have used their economic and political muscle to corner as many vaccine doses as possible, while most poor nations rely on the COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access — or COVAX — initiative by UNICEF, GAVI (vaccine alliance) and WHO to promote equitable access to the vaccines. Despite efforts at improving access, GAVI has declared that merely 27 percent of the vulnerable population in developing countries will benefit from COVAX vaccines this year. The distribution of the COVID-19 vaccines has once again exposed the reality of the world’s poor, who are routinely deprived of basic human rights, in general, and justice, in particular.

There are now increasing concerns of ‘vaccine apartheid’ — a stark inequality in global access to vaccines. While rich nations have rolled out massive vaccination drives following the availability and emergency authorisation of multiple vaccines, poorer nations see no hope of gaining access in the near future. This is despite repeated efforts since the onset of the pandemic to declare the COVID-19 vaccine a global public good, including an appeal from 115 international personalities and 19 Nobel laureates to adopt legal measures to ensure it is made available free of charge to all. Experts have also made several suggestions on how to operationalise such a global drive, such as a temporary waiver of intellectual property rights by the World Trade Organisation and governments to encourage emergency production to meet the global demand for vaccines. Despite repeated pleas calling for solidarity and global cooperation, rich countries have yet to adopt such measures.

The distribution of the COVID-19 vaccines has once again exposed the reality of the world’s poor, who are routinely deprived of basic human rights, in general, and justice, in particular.

Several observers have made comparisons between the emerging situation and the HIV/AIDS epidemic of the 1990s. The WHO has declared that while the production of COVID-19 vaccine doses has exceeded the number of global infections, equitable access is still far from reach as over 75 percent of these doses are concentrated in the rich nations, which comprise 60 percent of global GDP. The WHO has also warned against ‘vaccine nationalism,’ adding that at the current rate, most poor nations will not have access to vaccines for at least another year while rich nations will likely complete universal vaccination in 2021. This will mean delayed global immunity. Areas of affluence will achieve COVID-19 immunity while most of the world population will continue to struggle with a resurgence in infection, economic slowdown and the perpetuation of existing global inequity.

Vaccine nationalism: Threat to global cooperation

The main threat to global cooperation on vaccination is the growing vaccine nationalism across major manufacturing nations. Vaccine nationalism typically occurs when governments sign agreements with pharmaceutical manufacturers to pre-order vaccines, blocking the availability to other countries in the process. Other ways of practicing vaccine nationalism include when governments enter tacit or explicit agreements with local manufacturers to promote and protect global market shares for their vaccines. For instance, China recently announced a new visa policy for travellers, contingent on them taking the Chinese-made Sinovac vaccine. This is likely to have widespread repercussions since the WHO is yet to approve any of the Chinese vaccines.

Wealthy countries reportedly ordered over two million doses of the vaccine even as they were in trials, with several nations pre-ordering multiple doses per citizen. Governments now have more information (on efficacy and side effects) on each vaccine than they did when pre-ordering doses, and can establish clearer vaccination strategies for their populations. Under such circumstances, the massive stockpiling of vaccines — with no clear intention of using them — is myopic, selfish and suboptimal from the global perspective. The US, for instance, is holding several million doses of the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine but has not authorised its usage yet. Several other countries that have authorised its usage, such as Mexico, have requested this stockpile be released. Although the US announced it will ship four million doses of the vaccine to Canada and Mexico, it continues to hold large reserves without Food and Drug Administration approval for emergency usage. The US’s reluctance to share vaccines is also pushing several Latin American countries to enter deals with Russia and China.

The massive stockpiling of vaccines — with no clear intention of using them — is myopic, selfish and suboptimal from the global perspective.

The WHO has expressed concern over vaccine nationalism and rich countries cornering massive resources at the expense of global access. Even pharmaceutical firms appear concerned by vaccine nationalism. SII chief executive officer Adar Poonawalla has said that vaccine nationalism could derail WHO efforts to deliver two billion doses to poor and middle-income countries. Wealthy countries will likely achieve immunity due to the timely access to the vaccines, but the threat from new variants and mutations will remain if most countries remain under-vaccinated. The WHO has repeatedly warned that restrictions to getting the vaccines out widely will impact the collective ability to control COVID-19 and prevent variants from emerging. Although many pharmaceutical companies have said their vaccines are mostly effective against new variants with some “tweaks,” the experience of the past year has shown that even small “tweaks” take time and can threaten new and rapid contagions.

Countries are restricting supply of materials needed to make more vaccines which is leading to long delays and missed timelines across global manufacturers. For instance, the Biden administration invoked the Defence Production Act to block export of raw materials, and SII has already announced that the move will lead to delays in the production of Novavax vaccines for global supply.

Countries are restricting supply of materials needed to make more vaccines which is leading to long delays and missed timelines across global manufacturers.

Vaccines are also emerging as a means to expand global influence. Russia and China got an early foothold in Eastern Europe and Latin America with their indigenously developed vaccines. These vaccines do not have authorisation from the WHO yet, however, both countries have engaged in extensive media campaigns and have emerged as major suppliers to countries across Latin America, Africa and the Middle East. Given how quickly vaccines were developed and trials conducted (in less transparent ways in some instances), some countries have begun to revise vaccine efficacy results after conducting their own local trials. For instance, Brazil and Turkey have lowered the efficacy of China’s Sinovac vaccine. Trials in Turkey showed 83 percent efficacy and those in Brazil showed 50.4 percent efficacy, significantly lower than the claims of over 90 percent efficacy by Sinovac. At the same time, despite repeated attempts at negotiations, there is heightening tension between the European Union (EU) and UK. This has led to new rows over the supply of vaccines produced within the EU, and the EU could soon announce export bans on the vaccines.

There have also been concerns regarding price discrimination practices followed by manufacturers across different markets. For instance, South Africa revealed that it acquired 1.5 million doses of the Oxford-AstraZeneca at US$5.25, which is more than twice what the EU paid (US$2.15). But governments that have jointly funded the development of different vaccines have successfully negotiated for lower prices — the Moderna vaccine is cheaper in US than in Europe, while the Pfizer vaccine is cheaper in Europe than in the US. Importantly, AstraZeneca and Johnson & Johnson are the only two vaccine manufacturers to commit to not profit from the pandemic, which is why the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine is available at low rates around the world (about US$ 4) and is the leading candidate in the COVAX initiative.

Jostling by pharmaceutical companies, governments and trade blocs is likely to undermine public confidence and cause setbacks to the overall vaccination drive across countries.

More recently, the optics of vaccine nationalism has hit centre stage with several European countries suspending the use of the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine over concerns of patients developing blood clots. This decision will have far reaching consequences as the vaccination drive has been slow in most European countries and there is mounting domestic pressure. The WHO and drug regulators have cautioned against the hasty suspension of the vaccine citing no evidence that links it to developing blood clots, with the Europe’s medicines regulator saying it is “firmly convinced” of the safety and efficacy of the vaccine. This jostling by pharmaceutical companies, governments and trade blocs is likely to undermine public confidence and cause setbacks to the overall vaccination drive across countries.

Indian exceptionalism

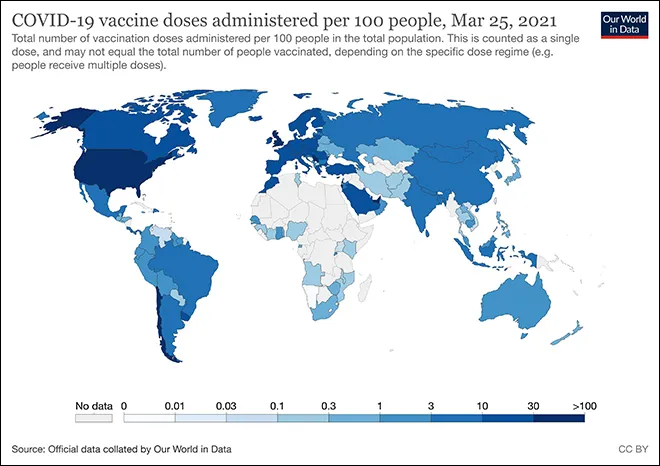

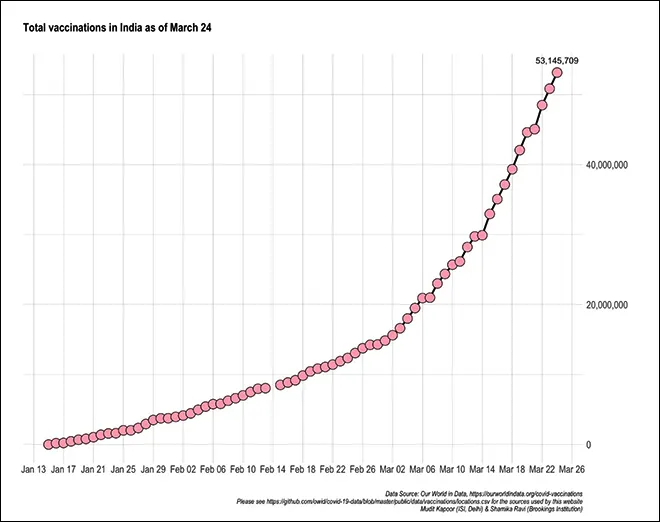

Amid evolving global tensions over the vaccines, India has emerged as a key player. It remains the only major COVID-19 vaccine-manufacturing country to actively supply to the global community while scaling up its domestic vaccination drive, leveraging its position as a leading pharmaceutical and vaccine manufacturing country. According to a submission to the Rajya Sabha by Ashwini Kumar Choubey, the minister of state for health, on 16 March, India had supplied nearly 60 million doses to over 71 countries, including neighbouring nations. By July 2021, India plans to vaccinate 300 million people across the country, and has rapidly scaled its vaccination drive since it began in January (see Figure 4). India has also benefited from local administrative capabilities that have developed through the experience of previous vaccination drives, such as those for polio and smallpox.

Figure 4: Total Vaccinations in India (as of 25 March 2021)

Source: Official data collated by Our World in Data, accessed on 25 March 2021.

Source: Official data collated by Our World in Data, accessed on 25 March 2021.

India is currently mass producing two COVID-19 vaccines — Covaxin, indigenously developed by Bharat Biotech in collaboration with the Indian Council of Medical Research and National Institute of Virology; and Covishield, as the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine manufactured by SII is known locally. Covishield, one of only two vaccines approved for ELU by the WHO, is among the most widely administered COVID-19 vaccines globally.

The uncertainty of the virus is being overshadowed by the growing uncertainty from vaccine nationalism.

India is not only supplying vaccines to other countries but is also participating in several initiatives to share clinical research and knowhow regarding mass vaccinations; the government is holding a series of training camps for partner countries like Bangladesh, Brazil, Bhutan, Myanmar, Oman and Nepal. At the recently concluded Quadrilateral Security Dialogue between India, US, Japan and Australia, the countries pledged to “expand and accelerate” COVID-19 vaccine production in India and to supply a billion doses of the vaccine across Asia and the Indo-Pacific by 2022. The US International Development Finance Corp will provide financing to Indian manufacturing firm Biological E to produce at least one billion doses of the Novavax and Johnson & Johnson vaccines, with supporting finance from Japan through concessional yen loans for India.

Conclusion

Amid escalating vaccine nationalism, is there any hope for global cooperation? The COVID-19 pandemic has mutated into a global political economy crisis, with new fault lines emerging along market shares and intellectual property regimes. Although the scientific knowhow and technology solutions have been developed in time through collaboration between governments and business entities across countries, the new constraints to the equitable access of vaccines arises from trade protectionism and limits to technology sharing due to existing intellectual property regimes. The uncertainty of the virus is being overshadowed by the growing uncertainty from vaccine nationalism. The challenge now is to expand vaccine production capacity and improve market access, which cannot be left to voluntary cooperation alone and must be resolved through global leadership to urgently transcend existing fractures. Global cooperation needs compulsory and explicit action. India has shown the way by becoming a major global vaccine supplier while simultaneously scaling up its domestic vaccination drive. Will wealthier nations follow this example?

Center for Systems Science and Engineering, Novel Coronavirus COVIP-19 (2019-nCOV) Data Repository, Johns Hopkins University, 2019.

R&D Team, The COVID-19 candidate vaccine landscape and tracker, WHO, 30 March 2021.

Gavi, “COVAX’” Gavi.

Priya Joi and James Fulker, “COVAX Supply Forecast reveals where and when COVID-19 vaccines will be delivered,” Gavi, 29 January 2021.

Winnie Byanyima, “A global vaccine apartheid is unfolding. People’s lives must come before profit,” UN Aids, 3 February 2021.

Yunus Centre, “Declare COVID-19 vaccine a global common good,” Yunus Centre.

Muhammad Yunus, Cam Donaldson and Jean-Luc Perron, “COVID-19 Vaccines A Global Common Good,” The Lancet, October 2020.

F. Hassan, “Don’t Let Drug Companies Create a System of Vaccine Apartheid,” Foreign Policy, Februrary 2021.

BMJ, Covid-19: WHO warns against “vaccine nationalism” or face further virus mutations, BMJ, 1 February 2021, pp. 372.

Julia Hollingsworth, “China opens its borders to foreigners who take Chinese shots, as geopolitical vaccine silos emerge,” CNN, 20 March 2021.

Ewen Callaway, “The unequal scramble for coronavirus vaccines — by the numbers,” Nature, 27 August 2020.

Adriana Barrera and Frank Jack Daniel, “Exclusive: Mexico focuses vaccine loan request on U.S. stockpile of AstraZeneca doses,” Reuters, 16 March 2021.

Jeff Mason, “U.S. to share 4 million doses of AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine with Mexico, Canada,” Reuters, 18 March 2021.

Dave Lawler, “Latin America turns to China and Russia for COVID-19 vaccines,” Reuters, 2 March 2021.

“Serum CEO Poonawalla says vaccine nationalism threatens WHO's 2021 goal to deliver 2 billion doses to poorer nations,” Hindustan Times, 17 March 2021.

“US decision to block raw material supply will hamper global efforts, warns Adar Poonawalla,” Business Today, 5 March 2021.

Chris Baraniuk, “Covid-19: What do we know about Sputnik V and other Russian vaccines?” BMJ, 19 March 2021.

Bret Schafer et al., “Influence-enza: How Russia, China, and Iran Have Shaped and Manipulated Coronavirus Vaccine Narratives,” Alliance for Securing Democracy, 6 March 2021.

Smriti Mallapaty, “China COVID vaccine reports mixed results — what does that mean for the pandemic?” Nature, 15 January 2021.

Laurence Norman, “EU, U.K. Seek to End Covid-19 Vaccine Fight as Bloc Broadens Export Controls,” The Wall Street Journal, 24 March 2021; “US decision to block raw material supply will hamper global efforts, warns Adar Poonawalla”

Owen Dyer, “Covid-19: Countries are learning what others paid for vaccines,” BMJ, 29 January 2021.

Rob Picheta, “EU regulator declares AstraZeneca vaccine safe, but experts fear damage has been done,”.

Picheta, “EU regulator declares AstraZeneca vaccine safe, but experts fear damage has been done”

“India shares vaccination and clinical research know-how for countries to customize and adapt,” WHO, 2 February 2021.

“Quad Leaders’ Joint statement: “The Spirit of the Quad”,” Ministry of External Affairs, 12 March 2021.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Source: 2019 Novel Coronavirus COVID-19 (2019-nCoV) Data Repository by Johns Hopkins CSSE Data update for India: 2021-03-25 05:27:00 (UTC); Population is based on UN estimates for 2020.

Source: 2019 Novel Coronavirus COVID-19 (2019-nCoV) Data Repository by Johns Hopkins CSSE Data update for India: 2021-03-25 05:27:00 (UTC); Population is based on UN estimates for 2020. Source: 2019 Novel Coronavirus COVID-19 (2019-nCoV) Data Repository by Johns Hopkins CSSE Data update for India: 2021-03-25 05:27:00 (UTC); Population is based on UN estimates for 2020.

Source: 2019 Novel Coronavirus COVID-19 (2019-nCoV) Data Repository by Johns Hopkins CSSE Data update for India: 2021-03-25 05:27:00 (UTC); Population is based on UN estimates for 2020. Source: Official data collated by Our World in Data, accessed on 25 March 2021.

Source: Official data collated by Our World in Data, accessed on 25 March 2021. Source: Official data collated by Our World in Data, accessed on 25 March 2021.

Source: Official data collated by Our World in Data, accessed on 25 March 2021. PREV

PREV