-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

Iceland is a small Nordic nation with a population of about 350,000. Historically, the country has been largely dependent on fishing. It wasn't until the late twentieth century that aluminium smelting took off in the country, which in 2008 accounted for 39 percent of exports and 17.5 percent of GDP. However, from the early 2000s, the financial sector of the country began to dominate its economy, so much so that the assets owned by the banks exceeded US $100 billion, about ten times the size of the Icelandic economy. Hence, when the Global Financial Crisis hit in 2008, it hit the Icelandic economy hard. Its banks were burdened with toxic assets due to their exposure to the subprime mortgages, the leading cause of the crisis. In addition to this, such investments were made through debt borrowed from the Dutch and English depositors, which made things even worse. Because of this weak foundation, the Icelandic economy was one of the worst affected by the crisis. Within a matter of months, the currency lost about 60 percent of its value, inflation increased, and unemployment levels rose to about nine percent.

But one of the outcomes of the crisis, the devalued currency, played a major role in putting the economy back on track. It made exports competitive and tourism relatively cheaper. Furthermore, the volcanic eruption of Eyjafjallajökull in 2010 gave a lot of publicity to Iceland and put it on the global map. What followed was a tourism boom in the country which led to double digit growth in the number of tourist visits year on year after 2010. In 2018 alone the number of tourists visiting Iceland was as high as seven times the population of the country.

Source: Statistics Iceland

Source: Statistics Iceland

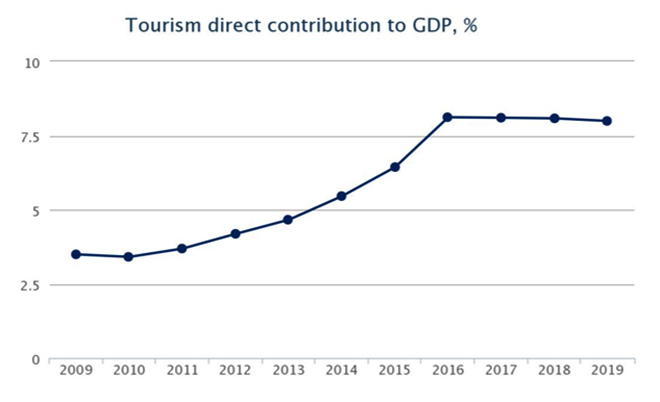

Tourism is one of the most crucial industry on the island, considering its direct and indirect contributions to the GDP, the massive share in exports and its influence on the exchange rate. The industry's direct share in the GDP has almost doubled over the last decade and today it accounts for nearly 40 percent of the exports of the country. As such, tourism played a major role in the recovery of the economy after the Global Financial Crisis, contributing about 40 to 50 percent in the economic recovery from 2010 to 2016, according to Landsbankinn Economic Research. In this time period the GDP of the country grew by ISK 462 billion (at current prices) and exports grew by ISK 246 billion; and about ISK 236 billion worth of increase in export income came directly from the tourism industry. Had the tourism industry not taken off, there would have been a massive trade account deficit in the country in the late 2010s (other factors remaining constant). As a result, the ISK would have depreciated even further and it would have led to high levels of inflation in the economy. Although the industry itself experienced a boom partly because of the depreciated currency, over the years it helped avoid further depreciation by providing a strong boost to the exports.

However, in recent years, the tourism industry has begun to lose its charm. The inflow of tourists is declining and contribution of the industry to the GDP has remained constant at about eight percent (as seen in the graph above) from the past four years. Recently the situation has become even worse, as the pandemic put a halt on travel and tourism across the globe. The number of departures from Keflavik Airport, the biggest hub for international transportation in the country, declined by over 96 percent from 2,56,000 passengers to about 11,000 in June as compared to the same month last year. The exponential growth in the industry, which helped the country recover from a crisis over a decade ago, was never going to be sustainable in the long run. Now, with the pandemic taking hold of the economy, any chances of an immediate recovery seem highly unlikely.

Besides tourism, fishing is also a crucial industry in Iceland. Being a stranded island in the middle of the ocean, fishing holds historical significance in the country. Even today, the industry employs about five percent of the total workforce and directly accounts for about 10 percent of the GDP of the country. But lately, questions have been raised with respect to the future and long-term viability of this industry in the country. Owing to Climate Change, the sea temperatures in the area have been rising and as a result of this, multiple fish species are now receding to cooler waters in the North. Although in the past, Iceland itself has benefitted from this phenomenon when species like the Atlantic Mackerel travelled north from the Norwegian waters to Icelandic waters. In 2018, the population of Capelin, an economically important fishery in Iceland, declined due to the warm waters. If the current predictions about climate change prevail, this problem of reducing fisheries is only going to amplify in the coming years.

As a new decade ushers in, it brings two major challenges for the Icelandic economy in the form of a pandemic and an ongoing trend of rising global temperatures. While the former has impacted the tourism industry, the latter poses a long-term threat to the stock of fisheries available in the country. Together these factors will adversely impact two of the major economic drivers of the country.

However, this crisis also presents an opportunity to Iceland to rethink its historical over-reliance on a few sectors and to make an effort to diversify its economy. Despite all the attempts at controlling these negative externalities, it remains to be seen how the country will be able to recover from yet another economic crisis.

The author is a Research Intern at ORF

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.