-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

Over the last decade, India’s patenting landscape has shown optimistic growth. A long-term strategic vision and certain measures could help the domestic patenting ecosystem become more future-ready.

Image Source: Getty

An evolved and optimally functioning patenting regime is a basic requirement for a knowledge-based economy. Technological innovation, invention, and scientific research require a robust patenting system, and the latter is especially important at a time when India’s startup ecosystem is witnessing exponential growth.

As of 31 December 2023, India has 117,254 recognised startups and these numbers are expected to rise steadily. Startups and other businesses need to be encouraged to commercially leverage their technological applications and innovations. While much work has already been undertaken to boost the Indian patent system, China and the United States (US) continue to lead the patenting race globally.

Technological innovation, invention, and scientific research require a robust patenting system, and the latter is especially important at a time when India’s startup ecosystem is witnessing exponential growth.

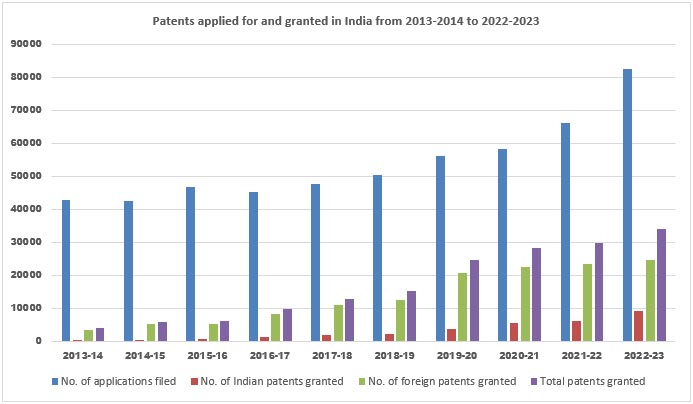

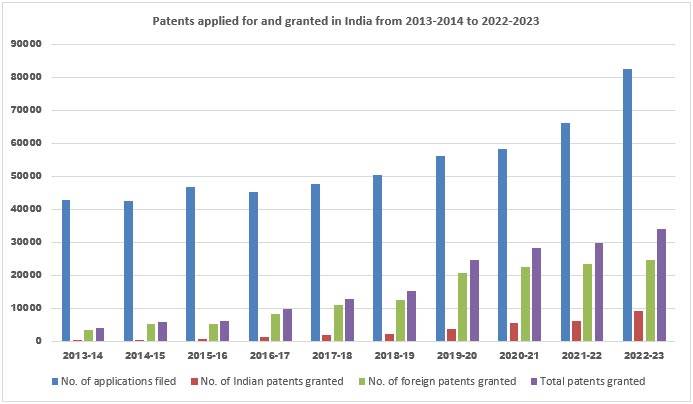

In recent years, India has shown marked growth with respect to the filing and granting of patents. In the year 2022-2023, a total of 82,811 patent applications were filed in India and 34,134 patents were granted. By comparison, 2013-2014 saw a total of 42,951 patent applications filed in the country and only 4,226 patents being granted. This is widely considered an encouraging sign of progress. The year-on-year growth of patent applications is heartening too—India received 25.2 percent more patent applications in the year 2022 than it did in 2021.

Source: IP India Annual Report, 2022-2023

As the graph above illustrates, however, the proportion of patent applications granted in India continues to be very small in relation to the number of patents filed. The number of foreign patents filed continues to enjoy a marked edge over local and indigenous patents.

The global innovation and patenting landscape continues to be dominated by China and US. Just in the year 2022 alone, China had received 1,619,268 patent applications followed by the US with 594,340 applications and Japan with 289,530 patent applications.

Figure 1: Number of patent applications across the world

Source: WIPO IP facts and figures, 2023

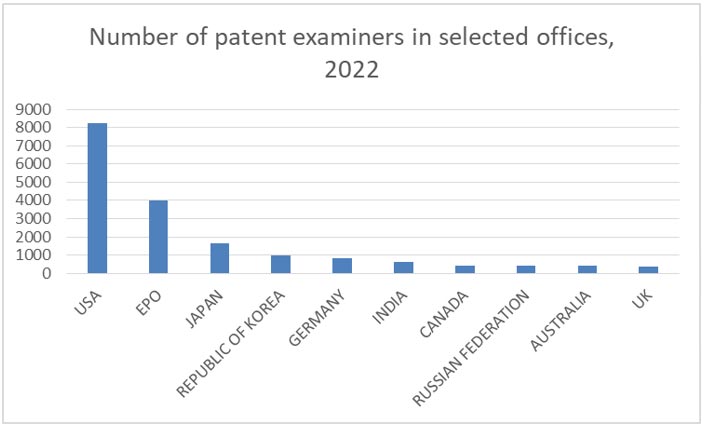

A close look at the number of examiners and controllers employed in the Indian patent office, and its comparison with the numbers in several other countries reveal a relatively low number of patent-related personnel. As of 2022-2023, India employs 858 examiners and controllers combined, across all its offices throughout the nation. In contrast, the US employed 8,132 examiners alone in the year 2022. This deficiency contributes to the low rate of processing of patent applications.

Figure 2: Number of Patent examiners

Source: World Intellectual Property Indicators, 2023

Despite this relative shortage, there is a marked upward trend in the workforce size employed in the Indian patent office. Efforts are ongoing to address this lack and there has been a perceptible increase in the number of examiners and controllers appointed over the last decade. For example, in 2016, there were 132 examiners and 139 controllers in the Indian patent office. Eight years later, the numbers stand at 593 and 241 respectively. This increase is likely to accelerate the processing of patenting applications and improve India’s patenting performance globally.

There have been strong arguments for the need to streamline compliance requirements for patents and make application and adjudication processes less cumbersome. This is likely to reduce the time taken for patents to be granted. The recently introduced Patents (Amendment) Rules, 2024 shortens the timeframe for various operational and compliance-related steps. This is expected to accelerate the pace of patent filing and issuance processes.

In light of India’s prevailing position in the patenting landscape and the challenges outlined above, the following recommendations may be considered:

The patent search service online portal could be made more user-friendly and could be aligned better with international best practices (e.g. ‘PATENTSCOPE’—the WIPO patent search portal). This will allow patent filers to conduct efficient due diligence searches for existing inventions in a comprehensive manner and thus avoid unnecessary duplication. Efforts can also be directed to simplify online patent e-filing procedures.

Virtual, interactive, and instantaneous problem-solving mechanisms could be incorporated into the portal to assist e-filers and patent searchers in real-time as and when any such problems arise, thus facilitating ease of doing business and much easier access and smooth utilisation of such facilities by the individuals who visit the Indian patent service portal.

According to Section 3, Subsection K of the Patents Act, 1970, the category of “computer programme per se” cannot be patented. In the era of continuous and exponential progress in ICTs and generative AI, the Government of India may wish to reconsider this policy choice as India may be losing out on possible opportunities for patenting GenAI families, and ICT inventions and thus incentivising further potential inventions in this space. Certain courts have begun torecognise the patentability of computer programmes if specific conditions are met. Nonetheless, a uniform national position is urgently required if India is to avail of the benefits and further growth opportunities that might organically flow from the commercialisation of such patented inventions.

Stronger joint efforts could be made to identify possible new areas for invention, and subsequently to consider the industrial applicability and commercial viability of these potential inventions.

India could further facilitate government-industry-academic interfaces to promote innovation. Stronger joint efforts could be made to identify possible new areas for invention, and subsequently to consider the industrial applicability and commercial viability of these potential inventions. Furthermore, industry-oriented, domain-specific academic curricula could be designed, corresponding skills imparted to students and focused research conducted. Industry associations have an important role to play in facilitating dialogue within the private sector, spreading awareness and improving patent literacy among innovators and investors. Concerted multistakeholder efforts could also be made to set up incubators, part of whose activities could focus on providing support for promising emerging innovations to be patented.

Finally, periodic upskilling programmes ought to be conducted for personnel of the Indian Patent Office. Increasing the number of controllers and examiners might also support the quicker examination and adjudication of patent specifications and associated claims, thus reducing processing times, and moving towards greater parity with industrial best practices in other geographies.

Debajyoti Chakravarty is a Research Assistant at the Observer Research Foundation

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Debajyoti Chakravarty is a Research Assistant at ORF’s Center for New Economic Diplomacy (CNED) and is based at ORF Kolkata. His work focuses on the use ...

Read More +