-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

While the right to education is widely recognised by national constitutions, its actual implementation remains inadequate

This essay is part of the series “Reimaging Education | International Day of Education 2024”

Over the decades, global governance structures have accorded utmost attention to the importance of education as a universal good. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), adopted in 1948, states in Article 26 the imperative of ‘Right to Education for all’, underlining education as an inalienable human right. Subsequently, many international legal proclamations have reiterated the need to extend the reach of education to the last mile, as education remains the sine qua non for the socio-economic amelioration of any modern society. As international proclamations and declarations remain largely customary, the national constitution is the de facto supreme edifice with legal force that drives the governance architecture of modern states. With the enactment of constitutions based on the ‘rule of law’ in different nation-states, the right to universal education became an explicit and integral part of the social contract that most of the sovereign states granted to its citizens.

As international proclamations and declarations remain largely customary, the national constitution is the de facto supreme edifice with legal force that drives the governance architecture of modern states.

The world commemorates 24 January as International Education Day, initiated by the United Nations to emphasise the role of education in fostering peace and development. In this context, the article will delve into the constitutional pronouncements of countries across the globe to understand how the different constitutional visions have perceived the imperative of imparting education to all its people and to what extent the constitutional promise has materialised so far. The constitutional vision is captured at two levels: First, whether ideationally, constitutions explicitly promise the right to education to its citizens; second, whether the constitutions have merely declared education as a right for its citizens or have gone ahead to underline special provisions to ensure that it becomes affordable for and accessible to the most marginalised sections of the citizenry as a marker of inclusive governance. Finally, the piece takes stock of the scale of educational attainment across these countries to measure the extent to which the constitutional guarantee of educational rights has been fructified.

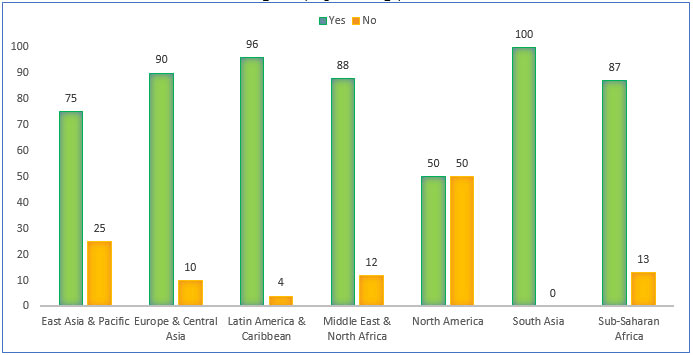

Recognising the potential of constitutionally entrenched commitments, a significant number of countries around the world have included explicit provisions guaranteeing the right to education in their constitutions. While only 63 percent of the constitutions adopted before the 1970s contained such provisions, all constitutions put into effect since the 2000s have pronounced an explicit constitutional approach to guaranteeing the right to education. Currently, as many as 152 countries worldwide guarantee the right to education, albeit with significant regional variations. All South Asian countries and most countries in Latin America and the Caribbean and Europe and Central Asia guarantee constitutional provisions for educational rights. In contrast, almost 25 to 12 percent of countries in East Asia & Pacific, Middle East and North Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa do not pronounce any specific provisions related to educational rights.

Figure 1: Number of countries with an explicit guarantee of the right to education across regions (in percentage)

Source: Authors’ own, data from Constitute Project

However, no two countries guarantee the right to education in the same manner. While many countries recognise education as a fundamental right and have provisions for it in their constitutions or national laws, the extent and nature of these rights vary greatly. Table 1 below presents a comparative analysis of educational rights in different regions around the world based on their score on three metrics—inclusivity (the levels of compulsory education covered under constitutional rights and the age until which education is compulsory), affordability (the nature of the educational institutions and associated costs) and accessibility (right to equal access to education and non-discrimination, except based on merit or competition).

Table 1: Educational Rights and Component Parameters

| Region | Inclusivity Score | Affordability Score | Accessibility Score |

| East Asia & Pacific | 0.29 | 0.26 | 0.07 |

| Europe & Central Asia | 0.46 | 0.47 | 0.17 |

| Latin America & Caribbean | 0.57 | 0.67 | 0.19 |

| Middle East & North Africa | 0.39 | 0.31 | 0.08 |

| North America | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| South Asia | 0.58 | 0.56 | 0.46 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 0.41 | 0.23 | 0.16 |

Source: Authors’ own, data from Constitute Project

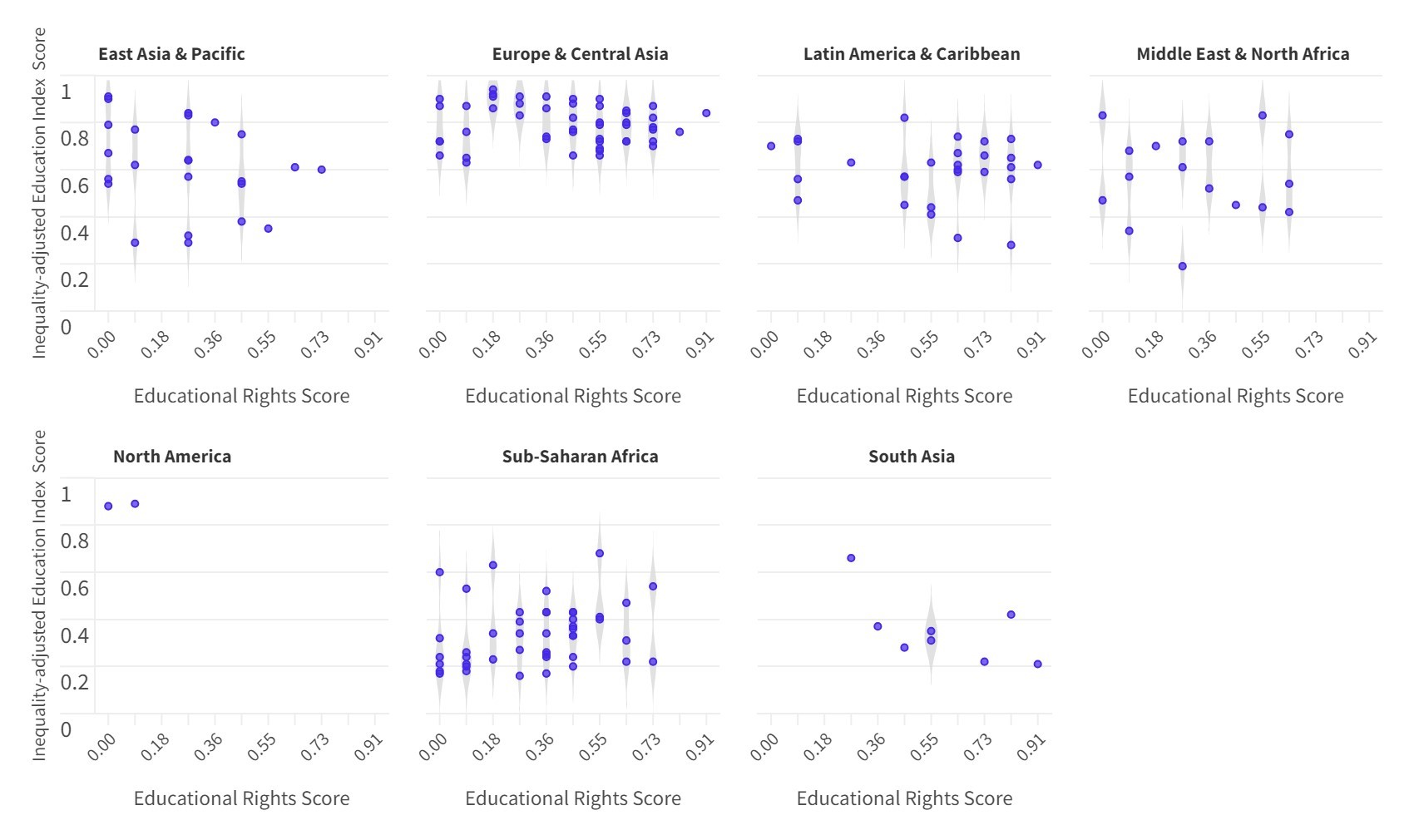

Beyond constitutional design, however, implementing these rights differs from country to country. In many developed nations like Germany, the government freely provides education across all levels despite no explicit constitutional provisions. At the same time, in some developing countries, the realisation of educational rights might be hampered by a lack of resources, political instability, cultural factors, or other challenges. Another aspect to consider is the presence of private education. In some countries, while education is a right, the government may not provide it directly, allowing private entities to offer educational services, sometimes at a cost. This marks the difference between legislation and practice. Figure 2 below clearly shows while the right to education is widely recognised and supported by international treaties and national constitutions, its actual implementation and the level of guarantee provided vary significantly from one country to another across regions. Despite a dearth of explicit constitutional provisions, many countries in East Asia and the Pacific, Europe, Central Asia, and North America have performed significantly well in advancing educational attainment across their populations while ensuring inclusivity. At the same time, some countries from Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia continue to confront significant challenges despite well-intentioned rights guaranteed to their citizenry.

Figure 2: Educational attainment vis-à-vis educational rights across countries

Source: Authors’ own, data from Constitute Project and Human Development Report 2021-22

Indeed, the increasing constitutional emphasis on education as one of the pivotal rights for citizens across the globe is a significant impetus for a global push towards ensuring greater access to education for all. However, a close look at the constitutional practice reveals that the actualisation of the educational right remains fraught with challenges for many.

First is the challenge of limited inclusivity that persists across the globe. Despite constitutional guarantees and state endeavours, many people still cannot access elementary education. A study underlines that 72 million children worldwide are still deprived of primary education as they lack access to schools. 759 million adults are languishing in the viciousness of illiteracy, incapable of ensuring socio-economic amelioration for themselves and their families. Such lack of access is attributed to the intersectionality of deep-rooted governmental, structural and societal factors. The lack of employment, malnutrition, inadequate institutional infrastructure, societal prejudice and ignorance towards education collectively enfeeble global constitutional efforts towards making education an inalienable human right. Sub-Saharan Africa, with 32 million children out of school, remains one of the most severely hit regions of the world in terms of inaccessibility to basic education opportunities. Also, regions like Central and Eastern Africa and pockets in the Pacific still record 27 million uneducated children who remain out of school. High school dropout rates mark these regions as the environment remains unconducive for children to continue school education.

The lack of employment, malnutrition, inadequate institutional infrastructure, societal prejudice and ignorance towards education collectively enfeeble global constitutional efforts towards making education an inalienable human right.

Second, there remains a severe gender-based exclusion in accessing education as significant sections of girl children remain out of school in many countries across the globe—constituting 54 percent of the total non-schooled population. The problem of gender imbalance in education remains acute in the Arabian countries and certain regions across central, Western and Southern Asia. Afghanistan, Somalia and Yemen are some of the worst-hit countries where girls’ education remains grossly neglected. Highly rigid conservative societal design and deeply embedded patriarchal norms remain significant impediments to girls’ education even today.

Apart from the lack of inclusivity in the access to education, the quality of education is under severe scrutiny in many countries. Through constitutional and legal measures, though the spectrum of access to education is gradually broadening, whether such measures can create capacity or ensure skill development amongst students remains uncertain. Several studies across countries have revealed that despite going to school, millions of children lack essential reading, writing, counting and comprehension skills. Though their enrolment in schools is seen as a marker of educational attainment, it fails to develop any skill or facilitate long-term capacity building and vocational training crucial for career advancement and employment opportunities for the children.

Several studies across countries have revealed that despite going to school, millions of children lack essential reading, writing, counting and comprehension skills.

Even at the societal level, as education is a critical instrument for producing efficient human capital, education outcomes bereft of any meaningful capacity development would hurt economic productivity and, in turn, national-building endeavours. The lack of infrastructural development, financial support, insufficient impactful training and meagre incentives to teachers for advancing innovative teaching techniques harm the overall quality of education. Non-traditional policy interventions like personalised teaching techniques based on the variegated learning needs of children need to be prioritised to usher in meaningful educational outcomes.

It is the need of the hour for the world to realise that the transition from high levels of school enrolment to quality and meaningful skill development outcomes will never be axiomatic. It needs to be carefully driven through sound and focused policy initiatives. Needless to say, the global efforts to foster a constitutional imagination of education as a critical citizens' right have made a gradual yet concerted effort to universalise education. However, ensuring the horizontal spread and substantive depth of educational rights in an inclusive and meaningful manner remains a battle half won.

Debosmita Sarkar is a Junior Fellow with the Sustainable Development and Inclusive Growth Programme Centre for New Economic Diplomacy at Observer Research Foundation.

Ambar Kumar Ghosh is an Associate Fellow at the Observer Research Foundation

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Debosmita Sarkar is an Associate Fellow with the SDGs and Inclusive Growth programme at the Centre for New Economic Diplomacy at Observer Research Foundation, India. Her ...

Read More +

Ambar Kumar Ghosh is an Associate Fellow under the Political Reforms and Governance Initiative at ORF Kolkata. His primary areas of research interest include studying ...

Read More +