India's first wave of the COVID-19 virus asserted a

higher mortality risk amongst the older population (60+ years), especially with pre-existing comorbidities. Studies globally have reiterated the increased risk for hospitalisation and case fatality rates in national-level data in several of the countries dealing with the virus.

Countries like Colombia and Chile have as high as 86 percent of all deaths amongst the elderly. Seventy percent of Peru's deaths are accounted for by the 60 and above population.

Despite very few states reporting age-segregated data, India follows the trend.

West Bengal, for example, shows a case-fatality rate of 7.45 percent amongst 75+ years and 3.41 percent for 60–75 years, age groups, compared to 0.32 percent in 31–45 years and 1.21 percent in 46–60 years age groups, as of 26

th November, 2021. In

Kerala, 54 percent of all deaths are among 60+ age group of senior citizens.

Nagaland's deaths too are concentrated in the 46+ years bracket, amounting to almost 70 percent of all deaths. Hypertension and diabetes are the most preeminent comorbidities leading to death.

In Kerala, 54 percent of all deaths are among 60+ age group of senior citizens. Nagaland's deaths too are concentrated in the 46+ years bracket, amounting to almost 70 percent of all deaths.

The

report of the Technical Group on Population Projections for India and States, 2011–2036, estimates that India has about 138 million elderly population (60+ years), constituting 71 million women and 67 million men. In 60 years, this age group has nearly doubled to 10.1 percent of the total population in 2021 and is expected to increase in the future continually. The highest proportions are concentrated in Kerala (16.49 percent), Tamil Nadu (13.64 percent), and Himachal Pradesh (13.04 percent).

Figure 1: Age-wise demographics of states in India (2021)

Unique needs and gendered vulnerability

While the proportion of elderly in India is comparatively lesser than in other developed nations, structural flaws and poor social protection leave them vulnerable. There is relatively lesser financial aid allotted to their care, limited geriatric health infrastructure, and scarcity in outreach activities. Nearly

70 percent of the elderly population depend on others for their day-to-day needs as per the NSS analysis from 2017–18. In crises like the COVID-19 pandemic, they are bereft of the social connections and attention they deserve, especially those with heavy care-dependent needs. Their stresses are amplified by their limited fluency in digital tools.

As newer technologies and advancements in medicine emerge with equally rapidly

falling fertility rates, the elderly population is rising worldwide. These demographic and epidemiological shift changes dynamics. This shift has transferred the country's burden of diseases to older people and has a gendered impact. Women live

longer and continue to bear a disproportionate volume of the financially uninsured population. With historic underrepresentation in the workforce and poor control over monetary assets in their working years, they also remain dependent on others, much more so than men.

Women live longer and continue to bear a disproportionate volume of the financially uninsured population.

Only about 10 percent of older women in rural areas and 11 percent of older women in urban areas are economically independent. In contrast, about 50-55 percent of older men were financially able in both urban and rural areas. The Periodic Labour Force Survey of 2018–19 also observes a difference of about 47 percent between men and women in their participation in economic activities in the 60–64 years age group. HelpAge India's

survey during early lockdowns (in June 2020) further found that the livelihoods of 65 percent of the older population have been antagonistically affected, with family support systems also strained. More so, their contribution to unpaid domestic chores and care responsibilities also remains nearly

double that of men (112 over 245 minutes) over the age of 60 years.

Such uneven, unfair structures make older women more vulnerable to adverse outcomes from COVID-19. While mortality from countries globally indicates a higher fatality for men, United Nations Population Fund (

UNFPA) estimates that

nutritional deficiencies, gender-based violence, poor literacy opportunities, access to digital tools, and vulnerability to poverty considerably aggravate risks for women. They are also more prone to chronic illnesses like hypertension, heart and lung diseases, cognitive decline, arthritis and diabetes. Anaemia, for one, continues throughout a woman's lifetime. As per

NFHS-5, amongst the age group of 15–49 years, 57 percent of women were anaemic compared to only 25 percent men. The difference of prevalence between the genders is also continually visible amongst 60+, wherein 5.9 percent women in

contrast to 3.1 percent men are anaemic. For diabetes mellitus, the prevalence is as high as 14 percent, with advanced states/UTs of Kerala, Goa, Delhi, and Tamil Nadu with higher proportions.

HelpAge India's survey during early lockdowns (in June 2020) further found that the livelihoods of 65 percent of the older population have been antagonistically affected, with family support systems also strained.

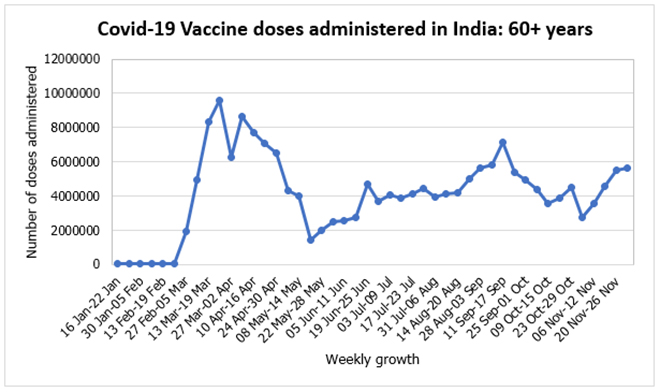

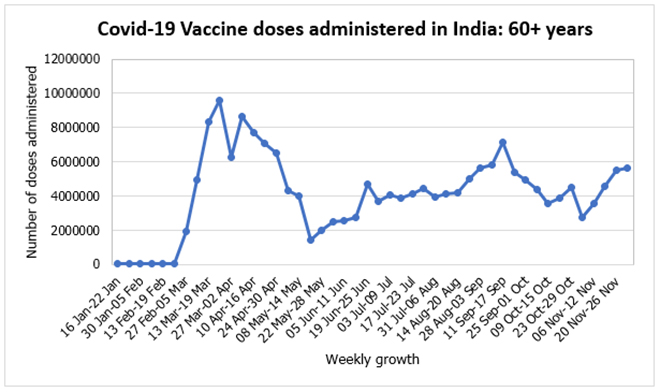

Figure 2: Trajectory of COVID-19 vaccination among 60+ years group

Source: CoWIN Dashboard

Source: CoWIN Dashboard

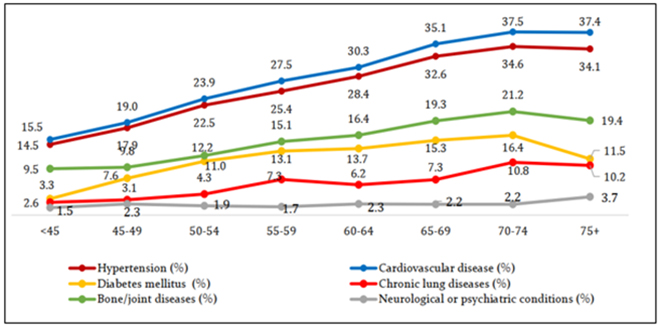

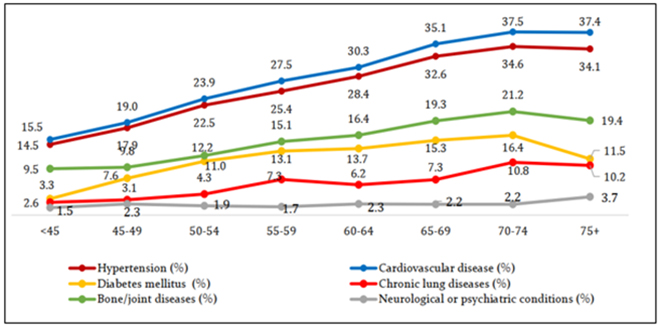

Amongst 60+ people, the prevalence rate of angina pectoris (a known risk factor for ischemic heart diseases caused by an insufficient supply of oxygen to the heart) is higher amongst women (7 percent) compared to men (5 percent). Moreover, angina is predominantly more common amongst women in the age group than a diagnosed heart condition. But the Longitudinal Ageing Study in India (LASI)

pointed out that the trend is quite the opposite for men and the general population. Additionally, the prevalence of high blood pressure was also higher amongst women (38 percent) than men (34 percent) in the group. Hence, this clearly suggests that the burden of undiagnosed heart conditions is also unjustly led by women in India. More importantly, the incidence of morbidities and multi-morbidities also increases with age progression.

Scientific studies have found that when compared to younger women, middle-aged and older women have a

higher prevalence of hypertension and need for invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV)s. This also leads to an increased risk of fatality. Some early reports suggested that middle-aged women are more likely to have

worse long-term health outcomes from COVID compared to men, while older women (over 50s) are dangerously more

susceptible to developing long-COVID. It can potentially hamper the quality of their later life.

Scientific studies have found that when compared to younger women, middle-aged and older women have a higher prevalence of hypertension and need for invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV)s.

Time for targeted COVID-19 vaccination campaigns for senior citizens

A national-level immunisation programme for senior citizens began early on in March 2021. It hit off with rapid intake in the first two months, largely by urban residents. But, it then dwindled drastically in May 2021 due to supply constraints and a critical

shift of the government's attention towards vaccinating the 18–-44 age group. Some early miscues in this massive undertaking were

misinformation, fear of side effects, poor smartphone-internet penetration and mobility. The impact of these barriers surfaced when the numbers never reached the initial peak again despite concentrated efforts in August and September 2021 (see below).

Figure 3: Self-reported prevalence of diagnosed major chronic health conditions amongst older adults by age, India, 2017–18

Source: Longitudinal Ageing Study in India

Source: Longitudinal Ageing Study in India

As of 30 November 2021, almost 125 million people have

missed their second dose of the vaccine, with most defaulters from Uttar Pradesh, Maharashtra and Rajasthan. Despite more than nine months of prioritised vaccinations for high-risk and the elderly, only

58 percent of India's 60+ years population is fully vaccinated. Jharkhand and Tamil Nadu rank last in their coverage with only

1,049 and 1,054 doses per 1,000 elderly population as of 3 December, 2021. The threat can be better understood by placing in context the high proportion of the elderly population in these states.

When the most vulnerable people remain unprotected, the looming threat of the third and recurring waves is never gone.

Vaccine hesitancy is a far-reaching concern in India, especially amongst the elderly.

Tamil Nadu's unwillingness to get vaccinated is

historical. The Public Health Department conducted a vaccine uptake survey in the state in July 2021, which revealed a 27.6 percent vaccine hesitancy amongst the 60+ population. Gender-wise, it was higher amongst males. Nagaland, another state grappling with hesitancy and misinformation, has the country's

lowest first dose coverage (56 percent as of 3 December, 2021). The poor

acceptance of vaccines is more pronounced in the 45+ years age bracket, contrary to its young population, and in districts of high illiteracy. Hence, when the most vulnerable people remain unprotected, the looming threat of the third and recurring waves is never gone. Taking cognizance of the slowed coverage, the Government of India instituted the

Har Ghar Dastak campaign and

Near to Home Vaccination Centres. However, its success is still capricious considering the other barriers that remain.

Conclusion

The discovery of more transmissible variants like Delta and Omicron necessitates protecting our exposed older population. Prioritising senior citizens in policy and practice can help nations prevent avoidable deaths. One way to facilitate such a shift is to adapt to age-responsive designs in interventional programmes and strengthen data systems to acknowledge the group's heterogeneity. As of now, more than 75 percent of the world's

countries have insufficient or no data on healthy ageing. Secondly, actions must be taken to enhance the penetration of health insurance schemes like the Indira Gandhi Pension scheme to reach rural areas where significant number of beneficiaries reside. COVID-19 is one of the many emergent diseases that hurt the elderly, but it surely won't be the last. The pandemic exposed the brutal ageism in popular discourse when medical resources became scarce. The needs of senior citizens continue to be trivialised and underestimated. But, to be discriminated as a life, less important than a young one, is no less than a

human rights violation. Inter-generational support and social protection need to be expanded and adapted to the inequitable ageing phenomenon globally to allow older people to be accepted and loved and let young people eventually age in assurance.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

India's first wave of the COVID-19 virus asserted a

India's first wave of the COVID-19 virus asserted a

PREV

PREV