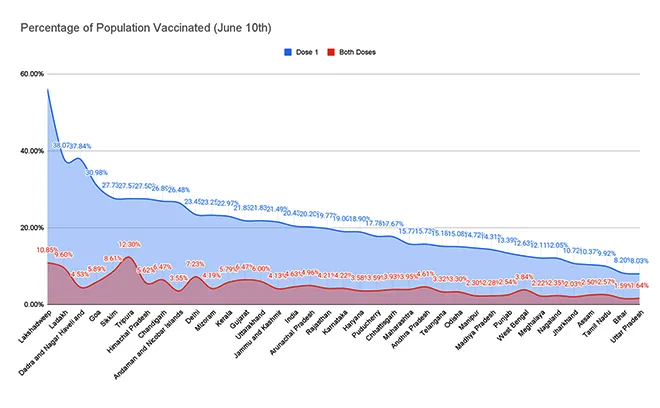

In January 2021, the Government of India gave emergency use authorisation to the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine (Covishield) and the BBV152 vaccine (Covaxin)—the first step in an ambitious programme to inoculate the world’s largest democracy. Several months later, as of June 14th, 15.4 percent of India’s population have received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccines and 3.6 percent have been fully vaccinated. However, this coverage is not consistent across the country, with some states doing better than others. Vaccine shortages and lack of robust healthcare structures is one reason for it; the other is a high level of vaccine hesitancy.

Vaccine hesitancy, or the reluctance, delay, or refusal to get a vaccine, despite the availability of vaccination services has been seen as one of the top ten global health threats by the World Health Organisation (WHO). Higher literacy rates, increased coverage of medical services, or even other higher socio-economic conditions could generally be assumed to be a deterrent to vaccine hesitancy; however, India’s southern state of Tamil Nadu has shown that to not be the case.

Higher literacy rates, increased coverage of medical services, or even other higher socio-economic conditions could generally be assumed to be a deterrent to vaccine hesitancy; however, India’s southern state of Tamil Nadu has shown that to not be the case

Tamil Nadu was tied second overall (with Himachal Pradesh) in the recently released NITI Aayog Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) Index. Despite having ranked high on developmental metrics, Tamil Nadu lags behind when it comes to vaccine coverage. The NITI Aayog SDG index found it to be the top state when it comes to poverty eradication, second highest state when it comes to good health and well-being, fifth highest in education, work and economic growth, and well ahead of the Indian average on all other indicators. Then why, the question arises, has Tamil Nadu lagged behind on COVID-19 vaccine coverage?

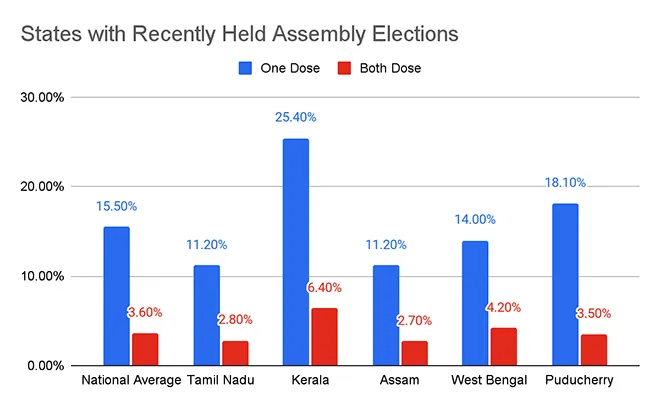

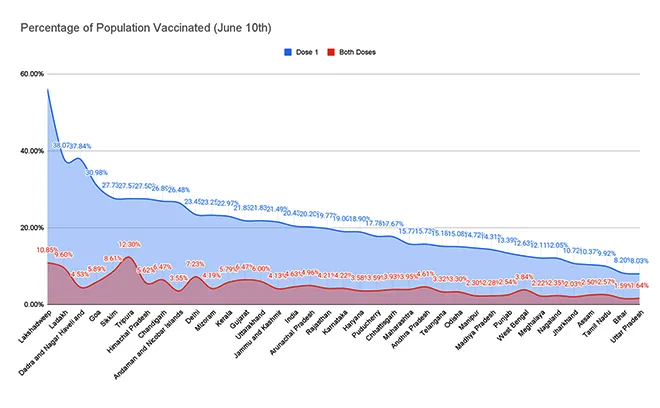

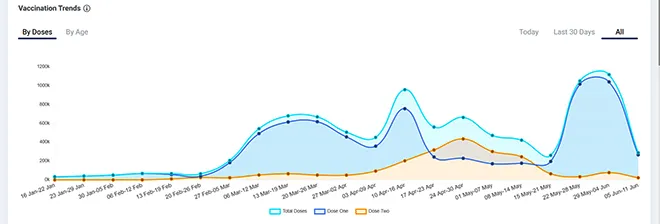

Source - CoWin Dashboard

Source - CoWin Dashboard

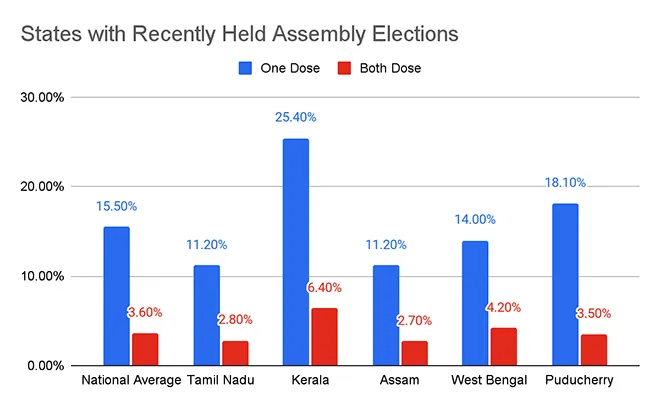

Only 11.2 percent of Tamil Nadu’s population has received at least one dose of the vaccine and 2.8 percent have been fully vaccinated. It not only lags considerably behind its neighbour Kerala, but even states like Jammu and Kashmir and Chhattisgarh. Interestingly, Tamil Nadu’s capital and district Chennai ranks in the top 10 when it comes to all indicators on vaccination coverage, including first dose administered, fully vaccinated percentage of population, second dose administered, and total doses administered. While an exact reason for this phenomenon is unavailable; perhaps, this is because of the higher number of centres, or a greater penetration of awareness campaigns.

From the lens of a historical trend, Tamil Nadu can be seen to have had a long history with vaccine hesitancy. NFHS numbers, on the coverage of basic immunisation amongst children, show that post the second round of the survey—which took place over 23 years ago between 1998 and 1999—the vaccine coverage reduced in the state. The most recent numbers from the fourth round of the survey (recorded in 2015-2016), are close to the numbers of the first round, undertaken almost 30 years ago—NFHS 1 (1992-1993) – 65 percent, NFHS 2 (1998-1999) – 89 percent, NFHS 3 (2005-2006) – 81 percent, and percent NFHS 4 (2015-2016) – 69 percent). The national average, while remaining lower than that of Tamil Nadu, has at the same time seen a considerable improvement. There is a higher coverage of vaccination in urban areas (81 percent) than rural areas (67 percent), with male children (72 percent) more likely to be vaccinated than female children (67 percent). This can be seen as an important indicator of behaviour around vaccines by parents—who today are the people receiving COVID-19 vaccines.

While nationally, illiteracy and ignorance were some of the key reasons for vaccine hesitancy, it is the opposite in Tamil Nadu

While nationally, illiteracy and ignorance were some of the key reasons for vaccine hesitancy, it is the opposite in Tamil Nadu. Previous studies on the coverage of the Measles-Rubella vaccination campaign found that the reasons for vaccine hesitancy have shifted from ignorance, to creation of suspicions and fear by negative news articles and rumours on social media, and print and digital media. Without disaggregated data around religion, caste or class lines for the COVID vaccine, it is difficult to draw a larger picture and understand where and why vaccine hesitancy is happening. Not so surprisingly, however, vaccine hesitancy was at the highest among families that trusted social media and news for health information, over healthcare workers.

Interestingly, in the initial phase of the vaccination program, which targeted healthcare workers, a high level of hesitancy was observed among healthcare workers themselves. Given their fight against the virus, healthcare workers in India today enjoy popular support and trust. When they choose not to take the vaccine, despite being in close contact with the virus, people are less likely to believe in the vaccine’s efficacy; but further, they are less likely to encourage the general public to take the vaccine. This hesitancy, combined with the lack of clear and reliable information disseminated by the government, both at the central and state level, is perhaps the reason why vaccine coverage rates remain so low in Tamil Nadu. In a space where news and social media is popular and easily available in the local language, and the society is largely literate enough to read it, fake news, conspiracy theories, and rumours become popular, reducing the level of trust towards the vaccine.

Understanding the COVID-19 vaccine challenge in Tamil Nadu

There are several reasons and challenges that have contributed to the high level of vaccine scepticism and hesitancy in the state. To begin with, given that the vaccine rollout began in a period during which cases had reduced, and the positivity rate was low, people in urban areas further believed that their tryst with the virus was over, and most people in rural areas believe that since the virus had not impacted them in the first wave, it wouldn’t in the second, leading to complacency.

Further, the introduction of the indigenous Covaxin vaccine was also surrounded by controversy, as it got a green light before the third phase trial results were declared. This controversy took a political turn, which took centre stage on news and social media. At the same time, both vaccine makers—Serum Institute of India and Bharat Biotech—came out with fact sheets that listed the people who should avoid taking the vaccine, which included a number of fairly common medical conditions like allergies and bleeding disorders. Unfortunately, the controversy reduced trust in the vaccine, and the lack of clarity between the two vaccines, and lack of information on who should opt for which vaccine further made people who had conditions like diabetes, blood pressure, or heart conditions less likely to take it. Given the high prevalence of such conditions in Tamil Nadu, and also that these conditions, in fact, worsen the impact of the virus, is an issue of much concern.

A lack of information around the side effects of the vaccine has reduced trust in two key ways. The death of popular actor Vivekh, who was also the face of the vaccine campaign in Tamil Nadu, became bait that conspiracy theorists were quick to catch hold of

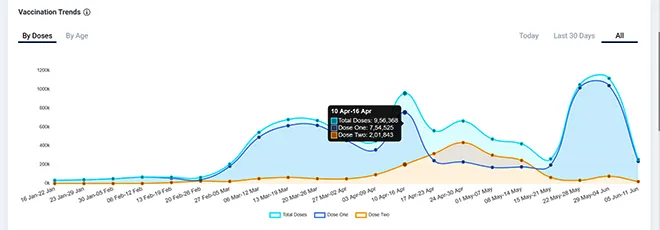

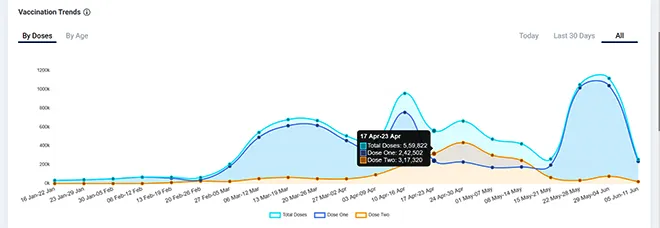

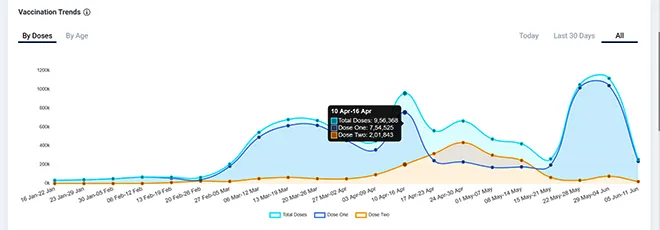

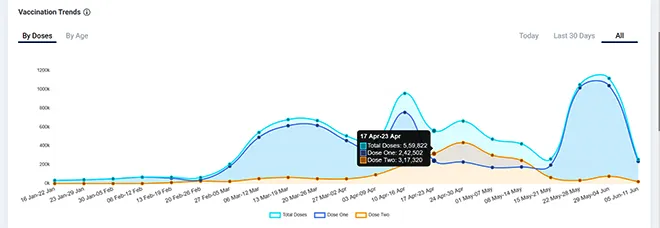

In addition to this, a lack of information around the side effects of the vaccine has reduced trust in two key ways. The death of popular actor Vivekh, who was also the face of the vaccine campaign in Tamil Nadu, became bait that conspiracy theorists were quick to catch hold of. His vaccination took place in a highly televised event that also saw the presence of the state’s Health Secretary and other important faces. His death two days later, from an unrelated cardiac arrest, caused many to believe that they could die from taking the vaccine, forcing the Health Secretary to host a press conference to resolve the issue. Nonetheless, the damage was done. In the week prior to his death 9,56,368 total doses were administered and the week post his death, only 5,59822 total doses were administered.

Vaccine coverage numbers from the week before the death of actor Vivekh

Vaccine coverage numbers from the week before the death of actor Vivekh

Vaccine coverage numbers from the week post the death of actor Vivekh

Vaccine coverage numbers from the week post the death of actor Vivekh

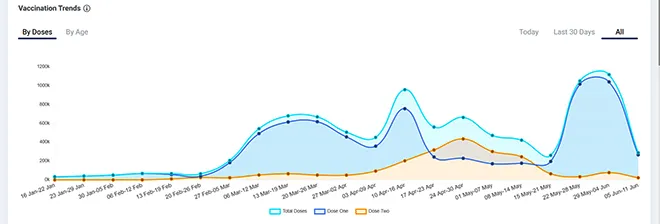

Overall vaccination trend

Overall vaccination trend

The fear of the side effects has further kept daily wage workers and those of the farming community away. The farming season is in full swing, and farm workers worry that the side effects of the vaccine may put them out of commission for a few days, impacting their harvest. For daily wage workers, the loss of a day or more’s wages is a concern. Additionally, they worry that if they were to develop side effects, they wouldn’t be able to afford medical attention, and given the pressure on health systems by the pandemic, they wouldn’t be able to access treatment. The hesitancy amongst the urban poor and the rural community was highlighted by the Health Minister of Tamil Nadu himself.

While, perhaps, not a central factor for this hesitancy—but is definitely one of the reasons for it—is the recently concluded assembly elections in the state. Given that political leadership was focused on winning seats, and the bureaucratic executive was distracted by the election, the virus and the vaccine did not remain a high priority. This is a consistent pattern that can be seen across the states and union territories that had elections, with the exception of Kerala, where the incumbent government enjoyed broad-based support due to its handling of the pandemic.

Conclusion

While the new issue developing in Tamil Nadu is that of vaccine shortage—in sync with the shortages seen nation-wide—understanding vaccine hesitancy is important not just for the coronavirus vaccination drive, but for other large scale immunisation programmes as well as other pandemics that may affect the world in the future.

While the new issue developing in Tamil Nadu is that of vaccine shortage—in sync with the shortages seen nation-wide—understanding vaccine hesitancy is important not just for the coronavirus vaccination drive, but for other large scale immunisation programmes as well as other pandemics that may affect the world in the future.

It is evident that the root cause of the problem is lack of understandable information. This affects not just illiterate people but also those literates who cannot understand complex medical information. In the absence of such reliable, easy-to-understand information, fake news and rumours start spreading. The latter’s easy language, long reach, and wide readership makes people believe in them and trust them. To counter this, it is perhaps imperative for the government to emerge with a highly publicised campaign—that fights myths around the virus and provides independent information. At the same time, it is also important for the government to reach the last mile in terms of creating access and knowledge around the virus. Involving ASHA workers has been seen as successful in other campaigns as well.

It is clear today that the best way to prevent waves of COVID-19 is vaccination. Unvaccinated people not only put themselves at risk, but also the people around them. In the absence of large-scale vaccination, the coronavirus will remain a challenge. It should, therefore, be a priority for the government to fight this hesitation.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV