-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

What is driving India’s abnormally high gender gap in phone ownership? What can be done about it?

Image Source: Meena Kadri/CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

India represents the second largest market for mobile phones and is the primary driver of growth in mobile subscriptions worldwide. But it’s a dominance led largely by men.

This is no surprise, given that Indian women lag behind in many areas such as labour markets, bank account access, and physical mobility.

Ironically, mobile phones have the potential to reduce these gender disparities. Phones have already proved successful platforms for various services that women typically lack, such as financial services.

If only it were the case, then, that Indian women had equal access to mobile phones. Yet they are 34.5 percentage points less likely to own a phone than men (FII, 2016).

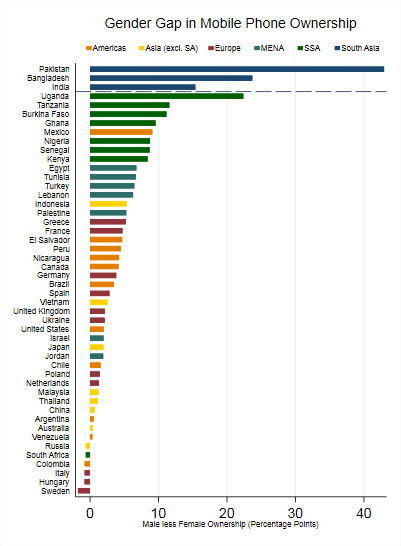

The graph below depicts cross-country estimates of the gender gap in mobile phone ownership from the Pew Global Attitudes survey. <1> Notably, India and its South Asian neighbours have wider gaps than many countries at similar levels of development like Indonesia. This challenges the conventional wisdom that gender gaps dissipate as countries develop.

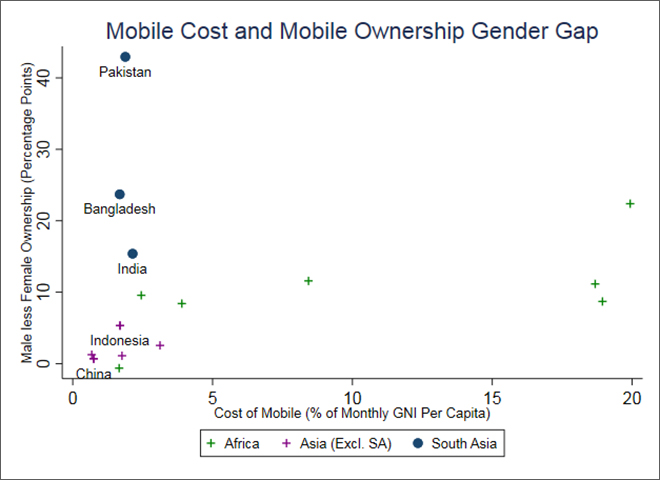

Ownership cost data are from the International Telecommunication Union (2014). GNI calculated using the Atlas method. Ownership gap data are averaged across 2014, 2015, 2016 and are from the Pew Global Attitudes Survey. The sample is restricted to countries where the male ownership rate is within 15% points of India’s male ownership rate.

Ownership cost data are from the International Telecommunication Union (2014). GNI calculated using the Atlas method. Ownership gap data are averaged across 2014, 2015, 2016 and are from the Pew Global Attitudes Survey. The sample is restricted to countries where the male ownership rate is within 15% points of India’s male ownership rate.

Furthermore, the ownership gap in India is large despite the fact that phone costs are among the lowest in the world. To illustrate this, Figure 2 graphs the cost of owning a phone against the gender gap using the same cross-country data. When compared to South Asia, many countries (e.g. China, Indonesia) have similarly priced phones but much smaller gender gaps.

Ownership data are averaged across 2014, 2015, 2016 and are from the Pew Global Attitudes Survey. The sample is restricted to countries where the male ownership rate is within 15% points of India’s male ownership rate.

Not only is this gap puzzling, but it is also troubling. If women continue to lag behind men in phone access, then the benefits of mobile phones will elude women and therefore only widen existing gaps. <2>

If not low economic development or high cost of phones, then what is driving India’s abnormally high gender gap in phone ownership? Most importantly, what can be done about it?

|

What are the main barriers to women’s mobile phone access? Economic Barriers

Normative Barriers

|

The short answer: it’s complicated.

One of us, Savannah, has been contributing to ongoing research by Evidence for Policy Design at Harvard Kennedy School (EPoD) in collaboration with IFMR. The main goal is to identify the leading constraints to Indian women’s mobile phone access. The research team has analysed several large-scale datasets, indepth interviews with Indian men and women, and past academic work on the topic.

On 14 December 2017, EPoD in collaboration with ORF convened a panel to discuss the initial findings from our research and to hear from Indian stakeholders including the private sector, think tanks and academia. The panel comprised of speakers, Ankhi Das, Director of Public Policy (India, South & Central Asia) for Facebook, Rohini Pande, Professor of Public Policy at Harvard Kennedy School, and Samir Saran, Vice President of Observer Research Foundation. The panel was moderated by veteran journalist Barkha Dutt.

The results of the research so far, presented by EPoD’s Research Director for India, Charity Troyer Moore, indicate that two broad factors constrain women’s phone access: economic constraints and normative barriers, meaning the traditions and cultural norms that govern women’s lives.

First, economic constraints: phone costs and technical literacy keep more women than men from using mobile phones. Handsets, especially for smartphones, are often too costly for women. Consequently, many women use a shared household phone if at all, most of whom borrow from their husband. Moreover, even when in possession of a phone, women report rationing phone use due to credit costs.

Phone costs and technical literacy keep more women than men from using mobile phones. Handsets, especially for smartphones, are often too costly for women.

Technical literacy also constrains women’s phone access: many women lack the skills required to operate a mobile phone. This leads women to feel uncomfortable using the full range of mobile phone features. As a result, many women depend on their husbands and sons when operating a mobile phone.

Second, normative barriers such as concerns with girls’ reputations, along with traditions dictating that women act as caregivers, limit their phone access.

Girls face immense pressure to preserve their purity in order to maintain a reputation suitable for marriage. Phones threaten this norm by facilitating access to others, thus causing communities to associate phones with impurity and elopements. This limits girls’ phone access prior to marriage and could explain why the gender gap in phone use emerges for girls during adolescence.

As purity norms wane after marriage, caregiver norms emerge. As a result, domestic obligations take precedence over women’s phone use, which is often seen as a sign that women are neglecting their household duties. Thus women limit their phone use to private settings in order to avoid being ridiculed.

Economic and normative barriers may appear to be distinct, but they often intersect to form complex constraints on female phone access.

Domestic obligations take precedence over women’s phone use, which is often seen as a sign that women are neglecting their household duties.

For example, caregiver norms could also keep a woman from taking a job, which in turn limits her personal income and ability to purchase a phone. Thus she depends on men (e.g. husbands, sons, fathers) for phone access. When she borrows a phone she reaps fewer benefits than if she owned one. Plus having to ask permission is additionally limiting. Ankhi Das during the event reiterated this finding noting the role of norms in restricting women’s access to phones. She said, “…when tradition becomes the social order which is set by the dominant elite, the elite being men who make the rules, there is a huge amount of cornering of resources. These normative values then govern the distribution of resources as well as the access to resources.”

Analysis of data from the Indian Human Development Survey (2012) also illustrates the complexity. Measures of women’s empowerment, household income, and education are each individually linked to women’s mobile phone use.

For example, the most empowered women in the sample are 36 percentage points more likely to use a phone than the least empowered. <3> This diminishes to 11 percentage points when we hold constant household income, education, and demographic characteristics. A similar story emerges for income and education. This implies that while norms and economic factors are individually important, they act alongside each other to form complex barriers to mobile phone use.

If policies are to succeed in increasing women’s access to technology, they must be conscious of this complexity. For instance, suppose policymakers aim to increase women’s phone ownership by providing handset subsidies. They would be remiss to not also address the caregiver norms that limit women’s phone use. Rohini Pande stressed on the need for public policy to target different individuals in a household adequately. She said, “We are now beginning to see in public policy some discussion about who do you target in the household, we have Ujwala scheme which should go to the woman, but when it comes to the digital part of public policy, I don’t think people have started thinking about that difference across individuals in the household.”

That said, more research is necessary before designing such policies. The research cited above is at best suggestive — it does not provide evidence of the kind of cause-and-effect relationships we would need to design policy. Rigorous analysis is required in order to disentangle the interlinked barriers and estimate their relative importance. Such analysis is key to directing resources efficiently towards closing the mobile phone gender gap.

<1> India's gender gap as illustrated in Figure 1 is a conservative estimate when compared to the gap cited in the previous sentence. This is likely because the Pew survey asks “Do you own a cell phone?” while FII asks “Do you personally own a mobile phone? By personally I mean that you use it the most and control how to use this phone?” While the FII captures phone ownership in a more meaningful way than the Pew survey, it does not survey as many countries as Pew. Thus we use Pew data for the cross-country comparison.

<2> For example, just 29% of internet users in India are female. Low female phone ownership likely exacerbates this issue since nearly 80% of internet access in India is through a mobile phone.

<3> Specifically, this refers to the top and bottom 10% of the distribution.

Savannah Noray is a Research Fellow at Evidence for Policy Design, Harvard University with inputs from Madhulika Srikumar, Junior Fellow, ORF.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Madhulika Srikumar was a 2019 India-U.S. Fellow at New America. Srikumar worked on India-U.S. data sharing for law enforcement and explored the underlying privacy standards ...

Read More +

Marc Jeuland Associate Professor of Public Policy and Global Health Duke University

Read More +