-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

The government’s measures to address affordable housing shortages offer hope across income groups. However, sustained commitment to continue these measures is crucial for its success.

Image Source: Getty

Cities worldwide, and especially in the Global South, are grappling with rising costs of housing, which has led to the proliferation of underserved informal settlements for the poor. In India’s urban districts, this problem is exacerbated by inadequate delivery of serviced land in the city periphery, irrational building regulations, cumbersome approvals processes and transactions, challenges in accessing construction finance, and high-risk/low-yield rental housing. India’s urban housing market is therefore characterised by an oversupply of high-end housing, low levels of affordable housing, and an insignificant rental housing supply.

Cities worldwide, and especially in the Global South, are grappling with rising costs of housing, which has led to the proliferation of underserved informal settlements for the poor.

A multi-pronged approach, where the state is ‘rightsized’ as an enabler and a provider, is imperative to improving access to affordable housing. Such an approach recognises the interconnectedness of housing markets and seeks to remove barriers across sub-markets. Initiatives like the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana-Urban (PMAY-U), which aims to facilitate 11.8 million houses in Indian cities by the end of 2024, exemplify such ‘rightsized’ market-enabling approaches that are tailored to bridge housing shortages and future demand.

PMAY-U seeks to bridge India’s housing shortage, pegged at 18.78 million units in 2012, with Economically Weaker Sections (EWS) and low-income groups (LIG) constituting 96 percent of this shortfall. PMAY-U encompasses the following four verticals:

PMAY-U thus attempts to meet diverse housing demands by offering supply- and demand-side provisionary support through these verticals. It captures the variance in housing demand through the urban local body (ULB)-level surveys, sets national targets based on the beneficiaries’ ‘vertical/intervention preference’, and supplements its interventions with other grants and reforms-based sub-missions, including the Atal Mission for Rejuvenation and Urban Transformation (AMRUT), Swachh Barat Mission (SBM), and the Deendayal Antyodaya Yojana-National Urban Livelihoods Mission (DAY-NULM). PMAY-U thus expands its focus beyond EWS/ LIG submarkets to include housing for all, rather than the “slum-free cities” premise of earlier housing programmes such as Basic Services for Urban Poor (BSUP) and Rajiv Awas Yojana (RAY).

PMAY-U’s demand-driven approach aims to strengthen cooperative federalism and create an enabling framework that allows national and state governments to ‘nudge’ incentive-driven self-investment implemented by ULBs and beneficiaries. It also leverages digital technology to minimise leakages and ensure that the benefits and subsidies reach the intended beneficiaries.

PMAY-U’s demand-driven approach aims to strengthen cooperative federalism and create an enabling framework that allows national and state governments to ‘nudge’ incentive-driven self-investment implemented by ULBs and beneficiaries.

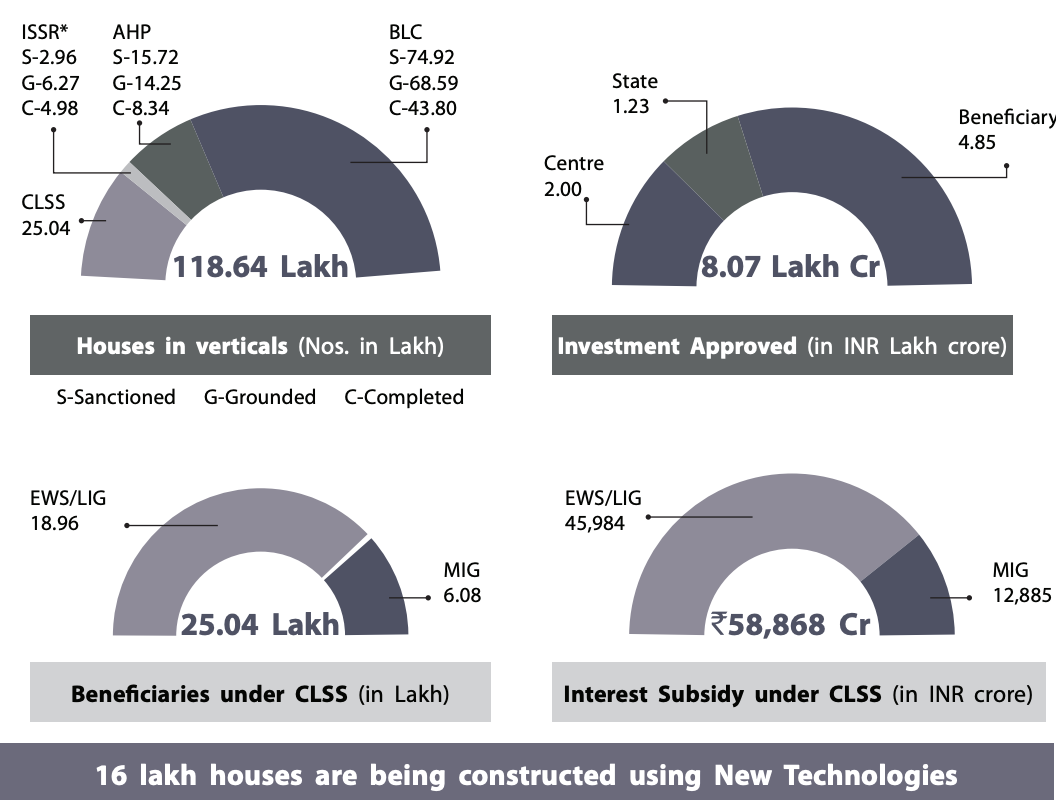

PMAY-U has empowered households to opt for self-constructed housing; since its launch in 2015, the BLC uptake has been 63 percent of total sanctioned units (Figure 1). As of 15 April 2024, PMAY-U had delivered 8.302 million houses (69 percent of sanctioned units of 118.64 million), with the remaining 3.498 million units at different stages of construction.

Figure 1: PMAY-U Status (as of 15 April 2024)

Source: Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs (2021)

The NULM provides transitional housing or shelters for the homeless in partnership with state governments. Enhancing the skills, enterprise, and assets of the poor is vital to help them climb to higher rungs of the housing ladder.

ISSR aims to transform slum-occupied land into formal dwellings with private participation. Developers get INR 100,000 per family in central assistance, while the state government acts as a market enabler by offering incentives such as additional Floor Space Index (FSI), Transferable Development Rights (TDR), and zoning variance, allowing the commercial exploitation of the projects’ ‘free sale’ components. The ULBs oversee bidding processes and approvals. Tenable slums on low-potential lands that are unlikely to inspire market-led redevelopment are upgraded with essential services through AMRUT and SBM.

ISSR has achieved mixed results, primarily because it focuses on building an ecosystem of cooperation and trust between the local government, developers, communities, and non-government organisations (NGOs) and intermediaries.

PMAY-U also offers guidelines for rehabilitating untenable slums on hazard-prone sites or reserved lands through ISSR projects with surplus lands, but their convergence lacks a clear roadmap. ISSR has achieved mixed results, primarily because it focuses on building an ecosystem of cooperation and trust between the local government, developers, communities, and non-government organisations (NGOs) and intermediaries.

CLSS, a demand-side intervention for ownership housing, provides low-interest loans to eligible EWS, LIG, and MIG families for home construction or enhancement. CLSS’s central nodal agencies— the National Housing Bank; Housing and Urban Development Corporation; and the State Bank of India—channel these subsidies to lending institutions and monitor the scheme’s progress. The beneficiaries can track applications via SMS alerts and a real-time CLSS AWAs Portal (CLAP) monitoring system. Digitalisation has enabled the faster processing of applications, validation, timely subsidy release, transparency, and reduce grievances.

BLC, another demand-side intervention, provides direct assistance of INR 150,000 to eligible EWS families for the construction of new houses or the enhancement of existing ones. BLC’s high demand, especially in small and medium-sized cities, stems from its comparative flexibility to allow beneficiaries to construct houses on their plots according to their needs and aspirations. The central assistance is released, by phase, after the utilisation certificates of funds and construction progress reports are submitted. BLC accounted for 58 percent (4.38 million) completed units out of the total sanctioned units of 7.49 million by April 2024.

A supply-side intervention, AHP provides financial assistance of INR 150,000 per EWS house built under different partnerships by states and ULBs. A project must have at least 250 houses, with a minimum reservation of 35 percent for EWS. States must release public land, make necessary DCR changes, reduce stamp duty, and provide matching assistance for AHP. AHP accounted for 53 percent (0.83 million) completed units of the total sanctioned units of 1.57 million by 2021.

India’s rental market, governed by state-specific Rent Control Acts that have become outdated, suffers from low yields (3 to 4.5 percent) and high risks and is riddled with tenant-landlord conflicts, some of which end up in litigation. Despite the housing shortage of 18.78 million in 2012, 11 million urban houses remained vacant across different cities due to lack of appropriate legislation and low rental yields.

India’s rental market, governed by state-specific Rent Control Acts that have become outdated, suffers from low yields (3 to 4.5 percent) and high risks and is riddled with tenant-landlord conflicts, some of which end up in litigation.

In order to address this gap, the Central Government introduced the Model Tenancy Act (2021) for rental housing along the lines of the Real Estate (Regulation and Development) Act (2016) for ownership housing. States are expected to adapt this by establishing Rules for an institutional dispute resolution framework that conforms to local contexts and comprises the rent authorities, courts, and tribunals. Although the Model Tenancy Act does not address low rental yields, along with the Affordable Rental Housing Complex (ARHC)[1], it is expected to unlock vacant stock and developers’ unabsorbed inventory and, in the long-run, incentivise rental housing.

ARHC aims to improve access to affordable rental housing for the homeless and slum dwellers through two models:

State and local governments enable suppliers by making changes in Development Control Regulations (DCRs). These include a 50-percent additional FSI and zoning variance for commercial development within the ARHC, delivery of on-site services, and single-window approvals for construction within 30 days of application.

Within two years of ARHC’s launch in 2020, about 83,534 vacant government-funded houses across 13 states were in different stages of implementation.

The Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs (MoHUA) has also made strategic market-enabling interventions to supplement the aforementioned provisionary initiatives.

Traditional urban policies have densified the core city areas while overlooking the expansion of serviced land on the fringes. Insufficient state- and city-level capacities constrain mechanisms like Town Planning Schemes (TPS) and local area-based planning (LAP). To address such gaps, MoHUA prepared a pilot TPS and LAP training programme supported by financial and technical assistance under AMRUT. Planning authorities of 25 states have availed of this programme towards expanding serviced land for housing in city peripheries.

Delays in securing permits after land acquisition, averaging 43 months, hamper project execution, incurring costs of 10-20 percent per housing unit. Responding to the World Bank’s Doing Business index, the Government of India initiated reforms to improve its global ranking, notably in the parameter of ‘Dealing with Construction Permits’. Consecutively, India’s rank improved from 182 in 2014 to 27 in 2020.

Mumbai and Delhi drove this improvement by introducing Online Building Permission Systems (OBPS) and other measures, reducing the average time to secure permits from 168 to 106 days and transaction costs from 28 to 4 percent of the project cost. MoHUA mandated OBPS as a condition for states and ULBs to qualify for AMRUT grants. As of April 2021, 1,705 cities, including 439 AMRUT cities, had established OBPS.

The Ministry of Finance and the Reserve Bank of India have taken several initiatives to address the ‘low-margin-high-risk’ scenario in mid-segment ‘affordable housing’, typically priced at INR 1 to 4.5 million. Under such initiatives, ‘affordable housing’ projects earn income tax and GST waivers and gain easy access to construction finance and home loans through Priority Sector Lending. Declaring affordable housing as ‘infrastructure’ also allows developers to access External Commercial Borrowing.

States and ULBs must align themselves with national measures by systemising surveys of household parameters, including income distribution, housing consumption patterns, and temporal housing flows and prices to accurately audit housing affordability in local land and labour markets and, accordingly, conduct occasional recalibration of interventions.

MoHUA’s ‘rightsized’ approach and measures to address affordable housing shortages offer hope for housing affordability and access across income groups. However, sustained commitment from state and local governments to continue on the reform path is crucial for its success. At the same time, it should be noted that the ongoing interventions are based on 2012 data. Considering the current urban scenario, central, state, and local governments should ensure that they do not face a ‘one step forward, two steps back’ situation. For example, studies predicted an increase in urban housing shortage from 18.78 million (a quarter of households) in 2012 to 47.3 million units (41 percent of households) in 2018. Considering the urban realities that the promised post-Lok Sabha elections Census will uncover, the national government must consider upgrading the mission to PMAY-U 2.0.

MoHUA must continue to conduct periodic performance and reform audits of ongoing housing initiatives. States and ULBs must align themselves with national measures by systemising surveys of household parameters, including income distribution, housing consumption patterns, and temporal housing flows and prices to accurately audit housing affordability in local land and labour markets and, accordingly, conduct occasional recalibration of interventions. Otherwise, ‘Housing for All’ would remain a pipedream.

Sejal Patel is a Professor and the Chair of the Housing Program at CEPT University, Ahmedabad and a Member of the High Level Committee on Urban Planning, Gujarat

This essay is part of a larger compendium “Policy and Institutional Imperatives for India’s Urban Renaissance”.

[1] PMAY-U’s new vertical, announced in July 2020.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Sejal Patel is a Professor and the Chair of the Housing Program at CEPT University, Ahmedabad and a Member of the High Level Committee on ...

Read More +