This article is part of the series Comprehensive Energy Monitor: India and the World

This article is part of the series Comprehensive Energy Monitor: India and the World

Staying warm in winter and cool in summer is not only a matter of comfort but also

essential for health. Heat stress is cited as the primary cause of death of at least 2000 people annually in India. Growth in the use of

air conditioners (ACs) in India driven by an increase in population number, increase in urbanization, increase in incomes, and an increase in average temperature, along with the affordability of ACs has limited heat stress-related casualties. However, ACs consume large quantities of electricity and use

hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) that contribute to the emission of greenhouse gases (GHGs), the primary cause of climate change. This contradiction highlights the most fundamental and contentious climate challenge: Will the increase in energy consumption of the poor masses for cooling and other energy services help them

adapt to a warmer world or contribute to a warmer world? The response reiterated in

domestic and

international climate literature is that efficient cooling technology will allow for an increase in AC use without increasing GHG emissions.

Stylised facts

Global residential AC ownership is estimated to be about

2.2 billion units in 2021. Across the world, households with ACs increased from about 25 percent in 2010 to about

35 percent in 2021. Households account for 68 percent of total AC installations globally. In 2020-21 space cooling energy consumption (including energy consumption by ACs, fans, coolers, etc) increased by more than

6 percent which was greater than growth in any other building end-use energy. Space cooling energy consumption has tripled since 1990 and doubled since 2000.

Worldwide, ACs consume over

2000 terawatt hours (TWh) of electricity every year, which is more than the total electricity generated by India in 2021 and roughly

7 percent of global electricity generation that year. CO

2 (carbon-di-oxide) emissions from space cooling have tripled since 1990 to over

1 GtCO2 (giga tonnes of carbon dioxide), equivalent to the total CO

2 emissions of Japan. According to estimates, a

1°C increase in temperature in the future will increase electricity consumption for space cooling by around 15 percent.

China produced around

70 percent of the world’s room ACs and accounted for about 22 percent of installed cooling capacity worldwide. AC sales grew fivefold since 2000, representing nearly

40 percent of global sales. China saw the fastest growth worldwide in energy demand for space cooling in buildings over the last two decades, increasing by

13 percent a year since 2000 and reaching nearly 400 terawatt-hours (TWh) of electricity consumption prior to the pandemic. Though more than

500 million units were sold in China in the last decade, relative AC demand rose more quickly in India and Indonesia, with average yearly installations increasing at a rate of more than

15 percent in India and

13 percent in Indonesia. India along with China and Indonesia are projected to account for most of the growth in energy use for space cooling by 2050. However, India is still far behind China in protecting its people from heat stress. The population-weighted heat stress exposure is

100 percent for India compared to China where the exposure is less than

20 percent.

Researchers have concluded that room ACs alone are set to account for over

130 GtCO2 between now and 2050. That would account for

20-40 percent of the world’s remaining “

carbon budget” (the most CO

2 we can emit while keeping global warming to less than 2˚C above pre-industrial levels). Many parts of the world experienced record-high temperatures in the last few years, and the global average number of

cooling degree days (CDDs, the number of degrees that a day's average temperature is above 18°Celsius), in 2020 was 15 percent higher than in 2000.

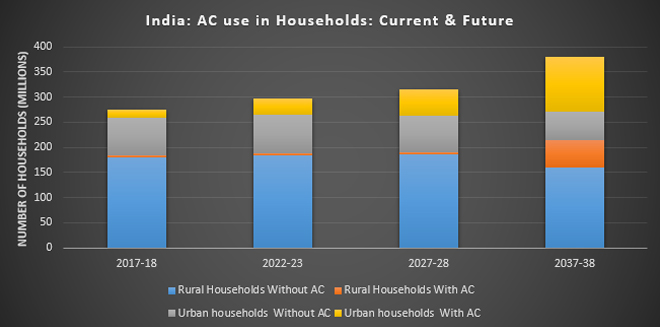

Source: MOEF&CC, 2018. India Cooling Action Plan (Draft)

Source: MOEF&CC, 2018. India Cooling Action Plan (Draft)

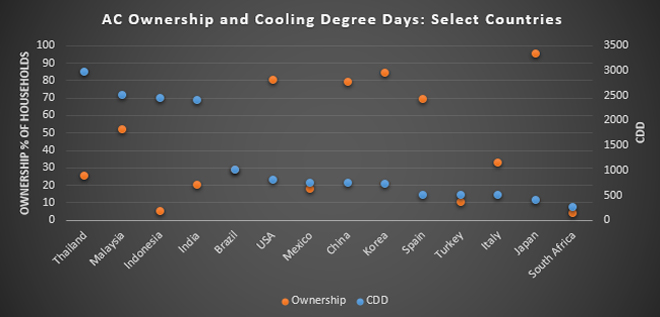

Disparities in Space Cooling

There are enormous disparities in access to space cooling across the world with the poorest countries located in tropical parts of the world having the lowest share of space cooling technologies. Out of the

35 percent of the world’s population living in countries where the average daily temperature is above 25°C, only

10 percent own an AC unit. India, which has more than

3000 CDDs consumes

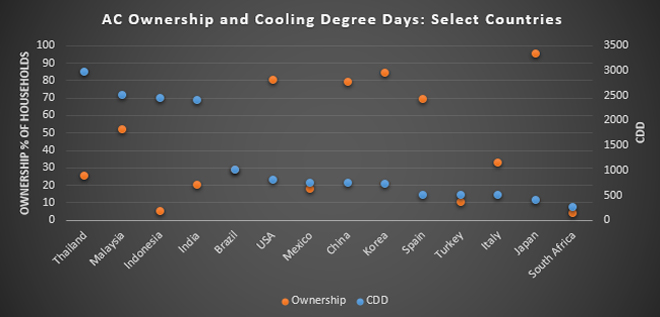

just 70 kilowatts hours (kWh) for space cooling compared to 800 kWh in South Korea which has only

750 CDDs. This disparity is mainly on account of the low affordability of AC use in India. Currently, less than

10 percent of Indian households own ACs but the demand is growing rapidly. Studies show that the correlation between

wealth and AC use is stronger than the correlation between climate and AC use.

Source: The Future of Air-Conditioning, Executive Briefing, Enerdata, 2019

Source: The Future of Air-Conditioning, Executive Briefing, Enerdata, 2019

Efficiency

As global average temperatures increase, AC use in India and elsewhere is likely to become more of a necessity than a luxury. Most of the detailed analysis of space cooling needs conclude that technology is the answer for improving the

efficiency of AC systems to substantially reduce electricity consumption and consequently GHG emissions. The average efficiency of ACs in India is relatively low given the cost-sensitive nature of the Indian market. Many of the suggestions from expert organisations propose stringent efficiency standards for ACs and incentives of the purchase of efficient ACs. Better building design,

increased renewables integration and smart controls are other measures that could reduce space cooling energy use and emissions and limit the power capacity additions required to meet peak electricity demand.

Other solutions that are commonly recommended are increasing

minimum energy performance standards closer to those of best-in-class ACs, which are typically

twice as efficient as the market norm. Government procurement agencies and large private-sector buyers (like real estate developers) leveraging their buying power in the form of advancing market commitments and

bulk procurement programs for super-efficient ACs is a workable solution. Simple financing solutions can encourage people to buy more efficient ACs. Forward-thinking distribution companies (discoms) can offer

‘on-bill’ financing, which allows consumers to pay for energy-efficient appliances on their electricity bills and in instalments - effectively enabling them to realise cash savings from the very first day.

Technology experts point out that the compressor technology at the heart of most AC units has barely reached

14 percent of its theoretical maximum efficiency (with most AC units in the six

-eight percent range). This is remarkably low compared to solar panels which have reached

40 percent of their theoretical efficiency potential and LED (light emitting diode) lighting which has reached 70 percent of its theoretical efficiency. Because consumers care about

price, brand, and appearance more than anything else, and regulators fail to apply much pressure on efficiency standards, AC manufacturers typically spend more on advertising and aesthetics than they do on research and development.

Issues

Even if all theoretically possible efficiency gains are achieved, AC use is likely to remain the privilege of the affluent and aspiring classes. In India, the per person carbon emissions of the lowest 50 percent of the population is

0.9 tonnes of CO

2 equivalent (tCO

2eq) and 1.2 tCO

2eq for the middle 40 percent compared to

9.6 tCO2eq for the top 10 percent. The use of an air conditioner consumes more electricity as compared to other electrical equipment in a typical affluent household in India accounts for a large share of the CO

2 emissions of the top

10 percent. What this means is that the poor and middle-class households that make negligible contributions to CO

2 emissions (from ACs and other energy-intensive devices) are likely to suffer most from heat stress. This is a micro-reflection of the larger challenge of climate change: the rich consume and emit carbon and the poor suffer the discomfort and consequences.

As Homer Simpson put it in the context of alcohol (as both the cause and solution to life’s problems), AC-use is likely to remain both the cause and solution to a warming world. But the rich will continue to add to the problem and they will also produce and use the solutions.

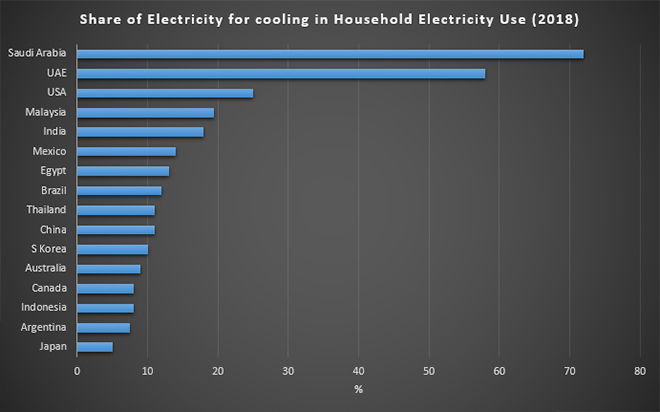

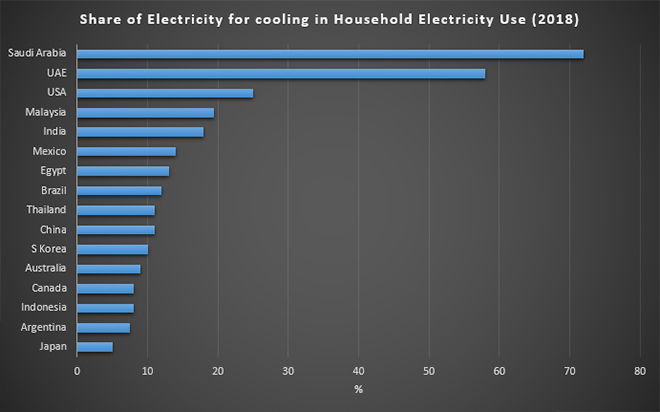

Source: The Future of Air-Conditioning, Executive Briefing, Enerdata, 2019

Source: The Future of Air-Conditioning, Executive Briefing, Enerdata, 2019

Lydia Powell is a Distinguished Fellow at the Observer Research Foundation.

Akhilesh Sati is a Program Manager at the Observer Research Foundation.

Vinod Kumar Tomar is a Assistant Manager at the Observer Research Foundation.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

This article is part of the series

This article is part of the series

PREV

PREV