-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

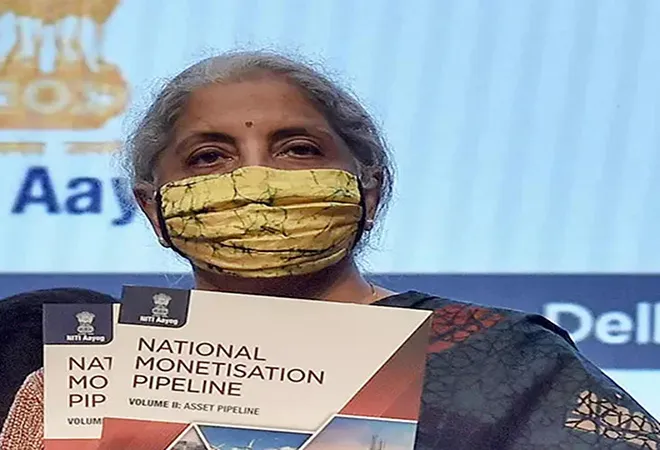

Weighing the pros and cons of the recently announced National Monetisation Pipeline

The Modi government launches new initiatives with blindsiding flamboyance. The National Monetisation Pipeline (NMP) announced August 23 does not disappoint. It targets raising INR 6 trillion over four years (Fiscal 2022 to 2025) by leasing out operational public sector assets.

The target for this year, with just six months in hand, is INR 0.9 trillion when disinvestment receipts are just 10 percent of the budgeted INR 0.75 trillion. The target for Fiscal 2024, just before general elections are held, is an even higher INR 1.9 trillion before tapering to INR 1.7 trillion in Fy2025.

Adding the future likely proceeds from the ongoing disinvestment program of sale of minority government shareholding in Public Sector Undertakings (PSUs) to the public and the new proceeds from leasing out assets, non-dbt capital receipts could double to a handsome 1 percent of GDP per year over Fiscal 2021 to 2024.

The target for this year, with just six months in hand, is INR 0.9 trillion when disinvestment receipts are just 10 percent of the budgeted INR 0.75 trillion.

The NMP is designed to boost government fiscal resources for another audacious infrastructure development program, launched in 2019, where the Union and state governments are to finance 45 percent of the estimated outlay of INR 111 trillion over six years till Fiscal 2025 with the residual 55 percent debt financed. The National Infrastructure Pipeline (NIP), envisages 8,160 projects of which 23 percent have started, although progress is slower than expected.

The NIP envisages nearly doubling public infrastructure investment to 10 percent of GDP from the 5.8 percent achieved (versus the target of 9 percent) during the 12th Plan 2012-2017 ning the waning years of the UPA and early years of the Modi government.

Sadly, however, the past trend is not supportive. Over the last two decades, infrastructure investment varied between a low of 5.2 percent of GDP (2002-2007) under Vajpayee’s NDA, to a high of 7.2 percent of GDP (2007-2012) under Manmohan Singh’s UPA. Departing significantly from this trend, in the face of global uncertainty and slowdown could either falter at the altar of over ambition or, if achieved, be truly transformational.

The National Infrastructure Pipeline (NIP), envisages 8,160 projects of which 23 percent have started, although progress is slower than expected.

Coming as the NMP does, two years after the NIP started and during the lingering pandemic, it is clearly a tactical move to deal with the immediate, adverse fiscal consequences of the domestic economic slow-down, heightened by the pandemic-related global meltdown, resulting in a “perfect storm” of a severely contracted GDP, widening fiscal deficit and rising public debt levels.

Monetising operational public assets as an additional source of much needed non-debt budgetary capital receipts is fiscally rational and mimics the deleveraging strategy corporates adopt, to sit-out a demand-compression-led economic downturn.

The resort to monetisation is also an outcome of relatively slow movement on two previous fiscal initiatives. One is privatisation—sale of majority government shareholding in Public Sector Undertakings with transfer of management control—attempted from 1999 but which petered out within after a few successes, as political resistance, including with the BJP, built up.

The second initiative is public private partnerships (PPP) started in 2010, but which floundered due to unsupportive governance structures, rigid contracts and rules aimed at “zero risk” decision making within the government, which crippled the convergence of public and commercial practices. The Kelkar Committee Report 2015 suggesting correctives, including monetisation, remains otherwise moribund.

Monetising operational public assets as an additional source of much needed non-debt budgetary capital receipts is fiscally rational and mimics the deleveraging strategy corporates adopt, to sit-out a demand-compression-led economic downturn.

In May 2020, Finance Minister Sitharaman stoked interest by including “privatisation” of non-strategic PSUs as an investment option. But even the privatisation of Air India became a victim of the pandemic-related economic disruptions.

The repeated assurances by the FM, whilst unveiling the NMP, that nothing is proposed to be sold illustrates that parting with “family silver” is still perceived as political suicide and that “economic reform by stealth” remains political salient.

Monetisation is a politically safe option, much like the hitherto favoured continuing “disinvestment of minority shares”, both of which avoid crossing the “sale of family silver” political Laxman Rekha.

Monetisation envisages lease of specific assets for 15 to 30 years to a private anchor investor who could either hold the asset in a corporate or in a specially created Investment Trust (InvIT), registered with SEBI, with minority shares issued to the public. InvIT’s attract specific long-term investors who look for secure, professionally managed secure options.

The government benefits from the receipt of lease rent annually or as an up-front consideration by the lessee, representing the present value of a portion of the profit expected to be earned by the lessee.

Monetisation trumps “disinvestment of minority shares” with respect to the value obtained by government. But it is an inferior option to “privatisation”. The differential valuation for the same asset relates to the degree of management control ceded by the government—none in disinvestment, complete in privatisation and complete but temporary in leasing.

Investors value management control highly, because it is key to enhance profitability. This value enhancing impact of full managerial control is evidenced by the differential growth in market capitalisation of listed PSUs—BSE PSU index lost market capitalisation since August 2011—even as listed privatized PSUs, like Maruti, increased market capitalisation by 6X and the BSE Sensex grew 3X.

Monetisation can enhance PSU productivity by restructuring business units without changing the enterprise ownership profile. Other than generating funds for growth, it enables a segmented strategy for enhancing productivity by “islanding” and leasing out business segments, possibly even with a guaranteed buy back of services—a parallel of the Business Process Outsourcing in the service industry.

Far from creating monopolies, the NMP could lay the foundation for a new class of next-gen infrastructure entrepreneurs.

Done right, monetisation can create a new class of mid-sized infrastructure entrepreneurs. Buying an entire PSU is a capital-intensive play. But if segments of their assets become available on lease, new entrepreneurs, with a lower net worth but a yen for infrastructure assets, can buy into the infrastructure space. Far from creating monopolies, the NMP could lay the foundation for a new class of next-gen infrastructure entrepreneurs.

A scaled-up program for revitalising public assets through private management and capital can attract patient capital in search of long term, stable returns—insurance companies, pension and sovereign wealth funds. Substantially expanded access to competitively priced, long term investment capital can help plug the 55 percent (INR 60 trillion) gap in the NIP outlay, after accounting for government resources.

Admittedly, there would be some disruption in public sector employment, just as in privatisation. A lessee might prefer a free hand to hire key managers, though retention of the skilled workforce is likely. One option is a wet lease, where the lessee takes the asset and agrees to safeguarding jobs. This constraint would lower the lease rent or up-front payment. But it seems appropriate to have employment safeguards in these hard times, when good jobs are scarce.

Are customers likely to be hurt through an increase in the prices charged for services? This is unlikely for two reasons. First, most operational infrastructure assets (power transmission lines, natural gas and petroleum pipelines, port jetties, airports) come with a regulated tariff determined on cost plus basis or via competitive bids at the time of getting the service license. Leased railway rolling stock would compete with tariff regulated, government owned train services. Any additional development or rehabilitation done by a lessee would be on terms regulated by the sector regulator or concerned administrative government department, as in the case of warehouses.

Privatisation of telecom and air transport services has reduced customer rates. Far from a surge in consumer prices, the real risk is of business loss for the lessee, from persistent discrimination against the new private operator of leased assets and regulatory uncertainty.

Any additional development or rehabilitation done by a lessee would be on terms regulated by the sector regulator or concerned administrative government department, as in the case of warehouses.

Done wrong, monetisation could result in crony capitalism via the consolidation of control by industrial oligarchs, in their respective sectors. But even monopolies can and are regulated. To tackle contractual contingencies, resilient sector regulators in electricity, petroleum and gas, airports and ports and administrative departments like railways, coal and mines, surface transport and the Competition Commission of India would need to remain vigilant of public interest being served.

Well-designed auctions have been successful in spectrum, power generation and coal mining. Good bid design includes preferring “more bidder skin in the game” versus tall promises of high but “back loaded” net benefit to government or indirect economic benefits from future capacity expansions. Monetisation must be preceded by a litmus test of enhanced net government receipt via lease rent versus the profits from continued operation. An alternative metric is the prospect of reducing an ongoing operational loss, as in Air India.

Monetisation of public assets is a second-best option to outright privatisation. End-of-lease transition arrangements can be painful. But it is a more beneficial option to the prevailing dominant disinvestment mechanism—sale of minority government shareholding in PSUs- both in terms of the direct budgetary receipts and the indirect positive economic impact on growth, tax revenue and good jobs. It is an idea whose time has come.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Sanjeev S. Ahluwalia has core skills in institutional analysis, energy and economic regulation and public financial management backed by eight years of project management experience ...

Read More +