Commercial Space Activities: A Wider Perspective

Commercial Space Activities: A Wider Perspective

Commercial Space efforts the world over have evolved on the foundations of government expenditures, particularly on military space programmes that created technological muscle in an industry used for spinning off commercial products and services. It was the deregulation drive for telecommunications that created, for the first time, a major opportunity for a competition-driven commercial space industry. This industry thrived on an enterprising private sector with the support of government policies. Integration of space infrastructure into the larger telecommunication industry, which is globally worth US $5 trillion annually, has enabled the creation of a large value chain for space telecommunication services. Comparatively, the size of the entire space economy, including all government budgets and commercial revenues, is US $330 billion annually. A revolutionary space-based capability, seen in the more recent past, had been the phenomenal growth of positioning and navigation services. Extension of satellite services in positioning and telecommunication to the mobile environments and the provision of direct consumer services through satellites are the twin opportunities that offer a great potential for expanding the markets, especially in emerging economies around the globe. It is in these markets that infrastructure is yet to fully develop to serve the underserved populations, and there are opportunities for manifesting several downstream value-building activities using space technology. Particularly for India, the consumption propensity of a strong middle-class population and the preferences of youth-dominated demography offer unique opportunities for market development.

There are, however, many challenges unique to space technologies. These include limited access to technologies, huge risks, and excessive government interventions. It is no secret that today’s dominant space industrial companies evolved and grew due to the huge military expenditure during the Cold War era. Industry consolidation over the decades, the technology-transfer constraints and the dual-use nature of space systems had led to concentrated markets and islands of capabilities on a global landscape. The metamorphosis came in the post-Cold War era, with the privatisation of intergovernmental systems, such as Intelsat and Inmarsat, and the segmentation of space activities to facilitate orientation towards free markets for space-based services, on the one hand, and tighter controls on dual-use technologies, on the other. The growth rate of commercial space had invariably been influenced and preceded by the policy drives in major markets, such as the United States. Until now, transformations in global space commerce had remained more policy driven than market driven. Therefore, when it comes to the review of India’s commercial space, the seminal role of policy dimensions cannot be undermined.

India’s Space Industry

The historical backdrop of industrial setting in India and the objectives for the origins of Indian space endeavours, which were non-military unlike those of advanced economies, did not facilitate India’s early entry into commercial space efforts. The priority for the Indian Space Programme, in its initial decades, was to achieve self-reliance and to develop a robust national industry to support the government-funded national programme, which had been conceived and executed by the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO). Further, the existence of well-developed national space industrial capabilities in key segments of space activities is a strength to rely upon for sustaining and growing commercial space efforts. ISRO’s forward-looking and well-thought strategies helped in building India’s space industry. As a result, India’s space industry is now extensive, though not fully integrated.

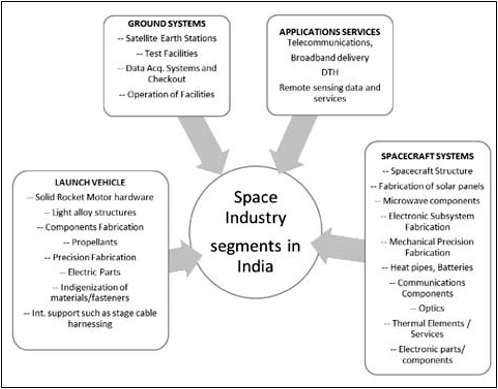

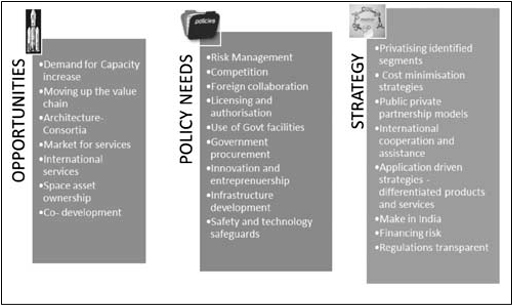

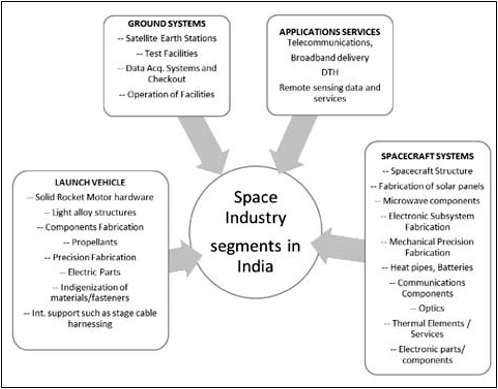

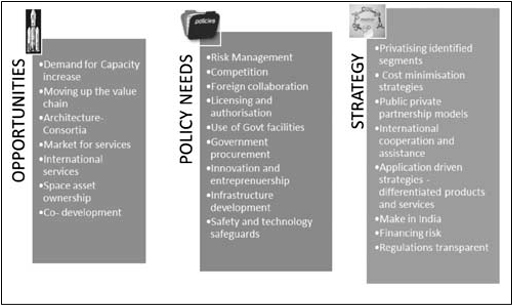

Indeed, the quest for industry partners for ISRO’s space projects began as early as when the developments of India’s maiden satellite launch vehicle, SLV-3, and the first Indian satellite, Aryabhata, were taken up in the early 1970s. Pioneering policies for technology transfer and industry development introduced in the mid-1970s resulted in multifarious initiatives, such as the creation of space divisions in industry, production of several components of space systems, building of specialised test equipment and ground facilities by the industry, and support for innovative space applications. The range of manufacturing and service rendering capabilities of the Indian space industry is illustrated in Fig. 1. The opportunities for space industry growth as well as policy renewal needs are illustrated in Fig. 2.

Fig 1. Indian Space Industry Capabilities

Fig 1. Indian Space Industry Capabilities

Fig 2. Indian Space Industry: Opportunities and Policy Needs

Fig 2. Indian Space Industry: Opportunities and Policy Needs

Leading Commercial Space Activities: ISRO’s Corporate Front

It was ISRO’s technology-transfer and industry-cooperation programme that sowed the seeds for India’s commercial space initiatives. During visioning exercises for the 1990s, the idea for formation of a corporate front for ISRO was mooted, to assist in the management of the rapidly expanding ISRO’s industry interface activities for its operational era. The concept for Antrix Corporation as a marketing arm of ISRO was concretised from the above idea. Considering the international dimensions of space activities, including the nature of space industry and commerce, authorities realised, even during that time, that Indian space industry should be globally relevant and should not lose sight of international opportunities and developing competitive strengths.

Antrix was incorporated in September 1992, as a private limited company, and was wholly owned by the Government of India, with the objective of promoting and commercially exploiting the space products developed by ISRO. It was initially intended that Antrix would undertake technical consultancy services and manage technology transfer activities of ISRO, to assist the Indian space industry. Since its inception in 1992 and until mid-2011, Antrix was managed by a board chaired by the Chairman of ISRO and the Secretary of the Department of Space. The members of the Board included key leaders of ISRO’s centres, responsible for satellites, launch vehicles and applications, and a few eminent leaders of the industry in the private sector. The integration at board level with top-level ISRO management is a key factor that ensured ISRO’s support to this company and allowed it to rely on ISRO’s infrastructure (both the facilities and expert technical human resources) in executing customers’ programmes. Due to the capital-intensive nature of space investments, high risks and the long gestation for returns on investments, it was initially planned that Antrix would not own expensive facilities or a large workforce, as found in many other public-sector enterprises, and would instead leverage the capacity created in Indian industries and in ISRO. Antrix, thus, aimed to set a new trend by adopting a very lean and efficient structure in ter ms of human resources. One of the priorities set by top leadership of ISRO, soon after Antrix began its operations, was that Antrix should play an enabling role for the growth of India’s space commerce using synergistic interactions with the space industry instead of doing everything by itself or reinventing the wheel.

Because of the wide diversity in ISRO’s activities and capabilities, the business portfolio of Antrix, too, was spread into many areas including: (i) provision of spacecraft systems, subsystems and components; (ii) remote- sensing services; (iii) satellite communications transponder leasing services; (iv) launch services; (v) mission-support services; (vi) ground systems; (vii) spacecraft-testing services; (viii) training and consultancy services.

Global Marketing of IRS data

Taking advantage of the contemporary features in ISRO’s fleet of remote- sensing satellites, Antrix began to market Indian Remote Sensing (IRS) Satellite data at very competitive costs. By establishing an alliance with one of the global leaders for marketing, Antrix began to provide data and downlinks in the US and other markets around the globe. This cooperation brought about a synergy of complementary capabilities available from Antrix and its US collaborator, Earth Observation Satellite (EOSAT) Company (later known as Space Imaging LLC.), resulting in a visible market impact. Over time, an international network of 20 ground stations were promoted in countries, such as the US, Ger many, Russia, China, Australia, UAE, Kazakhstan, Saudi Arabia, Thailand, Myanmar and Algeria, with the capability to directly access data from IRS satellites. Sustaining this segment of business had become a challenge over the years, in view of shrinking capacity due to increased domestic demands and increased competition. Nevertheless, it still presents an opportunity for the Indian industry to enter the business of satellite-based remote sensing, provided initiatives for support are forthcoming from the government. There have been continuous advances in this field of technology in India by way of ISRO’s programs, which can provide sustaining inputs for the commercial industry. Another major opportunity lies in creating an environment for the growth of the downstream industry, so that value addition by this segment in India can be maximised. One of the issues is access to high- quality images from space. Advances in information technology, especially for real-time processing and for analytics involving large volumes of data, growth of mobile communications and precise location capabilities have

transformed the very structure of value-adding industry by spawning a variety of services related to information and governance. Diversification towards mass markets and service focus are important drivers that the policy should address.

Commercial Launch Services

Commercial launch services for small and medium satellites with the well- proven Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle (PSLV) is a success that should be maintained. Notwithstanding the barriers of the launch market environment, Antrix successfully found international customers for launching small satellites from a score of countries including Germany, Korea, Belgium, Argentina, Indonesia, Israel and Italy on India’s PSLV, both in piggy back and primary payload modes. As of end-November 2016, a total of 79 satellites from international customers were launched

into orbit successfully by PSLV. PSLV has established a record of reliable flights, regular turnaround and flexibility for accommodating different types of orbits. Based on domestic and other commercial demands, in the future, ISRO is planning to launch 12 to 18 PSLVs per year.1 Moreover, there could also be demand for at least three to four Geosynchronous Satellite Launch Vehicles (GSLVs) annually, and commercial opportunities will increase once the GSLV Mark III version is operational. This means much more than just doubling the present capacity in the industry; the entire supply chain in space industry can benefit in addition to opportunities for new entrepreneurships.

It is also pertinent to note that the world’s launch services industry is not fully governed by market principles. There are concerns regarding technology safeguards and political considerations for trade in this area. The phases of development of launch capabilities across the globe are also uneven and have often given rise to conflicting interests among established players and new entrants. Such factors and balance of interests made negotiations for a Commercial Space Launch Agreement between the US and India difficult. Even recently, there have been reports2 that the US launch vehicle companies, including those working on a new generation of vehicles designed for dedicated Small Sat launches, have argued against easier access to the PSLV. Therefore, viability for a sustainable private

launch services industry in India is highly uncertain in the foreseeable future. If at all it is possible, only a public–private partnership model can be attempted, in which ISRO can farm out certain aspects of the launch vehicle manufacture and launch services business through long-term arrangements for risk sharing. Another major challenge that Indian launch services activities have to confront in the future is the disruptive cost trends triggered by developments in reusable vehicle technologies by private initiatives in the US. India’s investment strategies in space launch vehicles must consider seriously this changing trend in technology trajectory.

Marketing Telecommunication Satellites: Antrix– Astrium Alliance

Due to its modest launch vehicle capabilities in terms of launch mass, ISRO focused on development of relatively smaller satellites and has achieved heritage and proficiency in the same. Based on this niche capability, Antrix collaborated with EADS Astrium of Europe to jointly manufacture and supply communications satellites to global markets based on Indian satellite technology. This alliance has won two satellite contracts from prestigious European customers. ISRO-designed spacecraft platform, integrated with payloads from Astrium, were delivered to the customer. This alliance demonstrated effective industrial teaming of two different cultures for a common high-technology project. These types of models are very useful for Antrix, and for the Indian space industry in general, to enhance their global presence. Depending on the scope of collaboration, such alliances could also be considered for fulfilling offset obligations.

Satcom Policy and Its Objectives

India’s satellite communications policy (1999) came into effect in the backdrop of worldwide trends for satellite communication services by the private sector. The purpose3 of this policy was to build national capability in satellite communications through a healthy and thriving industry and through sustained use of India’s space capabilities. Another declared objective was to encourage and promote privatisation of satellite communications by attracting private-sector investments in space industry, as well as foreign investments. This policy also purported to make available Indian National Satellite System (INSAT) capacity to service providers in private sector for socially relevant applications. A set of norms, guidelines and procedures for implementation4 of this policy was approved by the Government of India in 2000.

In pursuance of this policy and the implementation processes that were evolved by ISRO/Department of Space in compliance with the decisions made by INSAT Coordination Committee, Antrix was mandated to market and manage the contracts for lease of capacity from INSATs or GSATs to Indian service providers. In case of short supply of capacity from INSAT, Antrix would lease from a foreign satellite operator to meet the demands of service providers in India, until capacity from Indian satellites was available. The service providers in all such cases were allowed to participate during discussions with foreign vendors (unless the capacity demanded was too small) while Antrix endeavoured to obtain the best bargains. Notwithstanding the relatively lower prices of satellite bandwidths as compared to other regions of the world, this procedure of canalising was a limitation according to the industry, and the latter demanded to replace it with an open-skies policy. The government needs to weigh the interests of a robust service industry, imperatives of autonomy in a critical infrastructure area, and a sound regulatory system ensuring national security. However, open-skies policy by itself need not conflict with these diverse goals. Moreover, putting all types of satellites in a single basket, extending the security argument and denying market opportunities will be neither convenient nor profitable to the space industry. Therefore, classifying satellites based on their capabilities is one viable approach. No one can deny that security is the prime concern of current times, for both the government and businesses. In the context of security, it is necessary to consider satellite as an element (albeit a critical one) in a complex network of infrastructure. The policy issue is also intertwined with considerations of international environment, which is characterised by restrictions on technology flows, quasi-permanent occupation of geostationary slots and limited nature of orbit-spectrum resources.

The time is now ripe to debate and review the policy statement of 1999, which aimed to promote privatisation of satellite communications by encouraging private-sector investments in space industry and by attracting foreign investments. Having established a large services market satellite TV and telecommunications, Indian space industry could be interested in making investments for owning and operating satellite assets. A serious dialogue is crucial between the industry and the government, on aspects of risk management, incentives and technological support. Since such evolution in Indian space industry is also possible through international collaboration, suitable clarity on regulatory and policy aspects is important.

By way of lessons learnt, a brief mention of Antrix–Devas Agreement is in order. Under this agreement, the broader aim was to establish nationwide direct satellite to mobile phone connectivity for multimedia applications, for the first time in the country, using a small satellite. The agreement was only for leasing capacity from satellite, which needed to prove a risky new antenna technology, to a service-providing enterprise. The service-providing enterprise, too, undertook the risk of developing a compatible ground segment. It was clearly stated that it was the service provider’s responsibility to obtain necessary service-related authorisations, including relevant frequency authorisations, payment of relevant spectrum fees operating licenses from concerned administrative authorities. Yet, there were misleading accusations and some inappropriate actions for cancellation, which brought about unsavoury legal consequences. Although such risk-sharing agreements between ISRO and industry is not new, in cases where unforeseen and rapid changes in techno-market conditions transform the value perceptions, the risk for controversy is higher.

There is a growing emphasis on opening markets for satellite services. At the same time, the industry segment relating to satellite infrastructure and launching activities are heavily regulated internationally and are influenced by the export control policies of different nations, which supply parts and components for space systems worldwide. While some of the impediments for accessing markets and production factors need to be overcome through political dialogue and international cooperation, a sound business strategy is also very important for overcoming already existing competition from global industries. Strategy for Indian industries’ foray into space segment ownership and operations, thus, need to be evolved through policy drivers formulated through the engagement of stakeholders.

Future Market Perspectives

The Continuing trend for deregulated industry in information and communication services in the context of a growing Indian economy, whose GDP is projected to attain a level of US $86 trillion by 2050, presents an unprecedented opportunity for a competition-driven growth for space-based services. The present-day capability of space systems to directly service individuals and homes (as in case of PNT or DTH or broad band delivery applications) enables a paradigm shift of these services towards mass markets, which has immense further potential to expand user base and diversify applications. This potential is well positioned by India’s demographic advantage in the coming few decades, because by the year 2050, there will be an expected 800 million working-age population. Further, the trends of economic development will also generate a huge and consuming middle-income group population. This augurs well for the expansion of a variety of information and communications services that can be supported through new generations of space systems, such as High-throughput satellites and constellations of agile, low-cost, high- performance remote-sensing spacecraft designed for providing on- demand services. Several applications including GIS-based decision support, positioning and location-based services, homeland security, disaster management, wide-band connectivity to remote rural areas and mobile multimedia ser vices represent significant untapped potentials. Even for established services such as direct TV broadcast to home, there had been demands for satellite capacity that exceeded the supply, over the past several years. Aforementioned applications will generate continuing demand for space systems and opportunities for international collaborations.

The trend of private-sector initiatives, in the US and elsewhere, to reduce launch costs through reusable systems and through other innovations are going to influence the developments in India as well, where demands will be up for enhancing launch capacities and lowering the cost of launches. New public-funded programs are likely in many areas, such as some segments of human space flights, planetary exploration through orbiters/ landers and rovers, insitu operations on planetary surfaces or asteroids, resource exploration on the moon and other celestial bodies, and participation in space tourism. These will generate additional work in the space industry and opportunities for entrepreneurship. Even with the yet-to-develop ecosystem for space entrepreneurship, the progress and entrepreneurial initiatives of Team Indus, Astrome Technologies, Bellatrix Aerospace, Dhruva Space, Earth2Orbit, etc., are highly pioneering, and such initiatives require greater support and encouragement.

Technology Trends

Miniaturisation of space components and systems enabled by increased use of solid-state power devices, new generation sensor devices, exponential growth in processing and data storage capabilities, enhancement of weight efficiency of energy storage and conversion, and process innovations such as concurrent engineering have greatly influenced reduction of launch and spacecraft costs. “New Space” era has also brought many disruptive concepts, such as miniaturised high-performance spacecraft, inflatable structures, large-scale clustering and constellations, greater autonomy in spacecraft, smart concepts in power, bandwidth and payload management, intelligent and robotic structures, and architectural integration in space and ground networks. While future developments in technology in the longer range will be directed towards increasing human presence in space, for creation of habitations, in situ operations and resource exploration, there will also be demands for technological developments for overcoming the challenges being brought about by the new trends in space as well as tackling global crises, such as climate change, terrorism, conflicts and uneven development. Space systems can be an important component of new generation systems needed for monitoring our planet’s health and natural resources on a continuous and long-term basis using networks of sensors far denser than the current ones. In this field, integration of space technologies and space-based applications with new tools/technologies, such as big data analytics and Internet of Things, can be expected. Advances will also be demanded for making space operations safer and more secure. This, in turn, will create an imperative of better Space Situational Awareness through global cooperation and pursuit of new steps for active debris removal or on-orbit repair missions. For India, through the next few decades, practical applications of space for better weather predictions and extreme-weather monitoring, applications in democratising information and towards empowerment, education and optimum use of natural resources and enhancing national security are greater priorities than esoteric pursuits of space endeavours. Convergence of space technologies with many terrestrial technologies, involving a ‘spin- in’ process, had begun to reduce the costs, and novel approaches are being experimented in the building of space systems. While India will continuously enhance its space transport capabilities, it can be expected that some intermediate steps will be pursued for cost reduction before large-scale reusability is attempted. Developments in air breathing engine technologies and semi-cryogenic stages will be advancements in this direction. Space rendezvous, docking and on-orbit robotic operations will also need to be tested. In summary, technology trajectories are complex to predict in view of interactions among multiple disciplines, which the space activities and future applications are likely to involve. For India, continued investment by the government is crucial if the country aspires to play a globally significant role in diplomacy, socio-economic advances and international security.

Policy Implications

The preceding discussion clearly indicates that India’s commercial space developments cannot be seen in isolation and must be viewed holistically, keeping in mind the multidimensional objectives that the National Space Policy will demand, besides imperatives of emerging international environment both in terms of the commercial and strategic aspects of the space domain. Major long-term policy implications for space commerce, given the potentials of India’s economic developmental aspirations, can be perceived as follows:

Target-Oriented Policies: Indian space-based service industry should be targeted to reach a level of US $40–50 billion by 2050. This is not unrealistic if economic development is sustained to predicted levels. In terms of market values, this represents an eight-to ten-fold increase over the next three decades. A robust infrastructure should be enabled by both government expenditure and private investments or through public–private partnerships.

Industr y Architecture: Recognising dimensions of space as a global activity, policies should enable and incentivise a balance of competitiveness and sustainability. There will be both hierarchy, e.g. a prime contractor and associated supply chain, and segment-wise specialisations based on value chain, e.g. infrastructure and services. A clear-cut policy is needed on collaborations. For security applications, the architecture and roles of space industry and their interface with government-owned facilities and regulation should differ.

National Space Ecosystem: India’s space industry should be modelled as an important part of the larger ecosystem, addressing space assets manufacturing, private ownership of space assets, national level space services and global market access.5 Indian space industry needs to orient for a quantum jump in technological growth and adopt organisational models that will ensure economic efficiency and enable a vibrant private sector.

International Coordination: The government needs to provide assistance to the space industry for safe and secure use of their assets in space, for Space Situation Awareness, and for an appropriate engagement with the industry to facilitate internationally coordinated resources such as orbit- spectrum coordination.

Governance and Regulation: The structures for governance for national space and commercial activities should recognise new stakeholders and, accordingly, involve them in ensuring proper governance of space activities as well as the commercial sector. Regulatory system should be renewed to ensure independence, transparency and adequate coverage.

Concluding Remarks

In pursuit of the government-funded space programme over the past five decades, ISRO has made some remarkable achievements, including autonomous access to space and making and operating state-of-the-art satellites that became the mainstay for television, telecommunication and the image-applications industry, with a multibillion-dollar domestic market. Opportunities are opening up to expand commercial space role of the Indian industry, though the challenges that confront these opportunities are daunting, and they demand a well-crafted strategy of engagement between government and industry, with a long-term perspective. The world has witnessed mainly policy driven forays in commercial space activities and, more recently, a new breed of entrepreneurship in the western world, challenging the traditional concepts and approaches. The potentials for space commerce must be tapped by promoting an overall ecosystem for space activities, which should serve to advance robust national space capacities, innovation in technologies and applications in commercial and non-commercial domains. There is also an urgent need for renewing policy and regulatory systems for incentivising the growth of India’s space industry.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful for the selfless, unflinching and dedicated support of my erstwhile colleagues in ISRO and Antrix, too many to name here, who made my journey in Antrix Corporation exciting and won the company a global recognition. I am beholden to the outstanding leaders Prof. Satish Dhawan, Dr. U. R. Rao and Dr. K. Kasturirangan for the high values that they inspired in me, which reflected in my healthy relations with collaborators and customers across the globe. I thank the dynamic leadership of Dr. Madhavan Nair, who gave a great growth impetus to commercial space activities; Dr. V. Siddhartha, who was the first chairman of ISRO’s Technology Transfer Group and played a pioneering role in seeding professional systems for technology transfers and industry interface; his successor Mr. P. Sudarsan, who championed the concept for Antrix at the very beginning; and late Mr. Sampath, who steered the challenging initial years. Both Mr. P. Sudarsan and Mr. Sampath had been my senior co-alumni at the Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad. Finally, I thank Mr. N. Rangachary and Mr. Sisir Das, public servants of high order and rare qualities, who provided valuable guidance to Antrix.

This article originally appeared in Space India 2.0

REFERENCES

- “PSLV-C 37 scheduled for launch on Jan 27,” The Hindu, Weekly Edition,

18 December 2016, ISSN 0971-751X. http://www.thehindu.com/sci-tech/science/PSLV-C-37-scheduled-for-launch-on-January-27/article16895637.ece

- Jeff Foust,”House committee seeks details on Indian launch policy,” Space News, 6 July 2016,accessed on 29 December 2016, http://spacenews.com/house-committee-seeks-details-on-indian-launch-policy/

- Indian Space Research Organisation, accessed on 16 December 2016, http://www.isro.gov.in/indias-space-policy.

- Department of Space, accessed on 22December 2016, http://dos.gov.in/

sites/default/files/SATCOM-norms.pdf.

- Mukund Kadursrinivas Rao, K. R. Sridhara Murthi and Baldev Raj, “Indian Space: Toward a ‘National Ecosystem’ for Future Space Activities,” New Space, 1 December 2016, 4(4): 228–236.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Commercial Space Activities: A Wider Perspective

Commercial Space Activities: A Wider Perspective

Fig 1. Indian Space Industry Capabilities

Fig 1. Indian Space Industry Capabilities Fig 2. Indian Space Industry: Opportunities and Policy Needs

Fig 2. Indian Space Industry: Opportunities and Policy Needs PREV

PREV