-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

All eyes will be focused on the reaction of the opposition, the stance of the military, gestures from the President-elect and reaction of the international community for clarity around whether political tensions will escalate to crisis levels or simmer down.

The results of the much-anticipated Zimbabwean election have been declared but the political environment remains fraught with tension. After a controversial election which saw result delays, a clampdown on media freedom, post-electoral violence, six deaths, and the arrest of a high-ranking opposition official, Zimbabwe now faces the pressing question — what next?

Although incumbent President Emmerson Mnangagwa won the Presidential ballot with 50.8% and the ruling Zimbabwe African National Union — Patriotic Front (Zanu-PF) obtained a two-thirds majority according to the Zimbabwe Electoral Commission (ZEC), the opposition have declared the result null and void. This has set the stage set for a period of contestation, both in the courts and on the streets — which will see Mnangagwa and Zanu-PF’s victory come under scrutiny.

In this post-election period, all eyes will be focused on the reaction of the opposition, the stance of the military, gestures from the President-elect and reaction of the international community for clarity around whether political tensions will escalate to crisis levels or simmer down.

With this in mind, we preview what is likely to transpire in the coming few days.

First, a legal challenge to the results by main opposition presidential candidate, Nelson Chamisa and his MDC Alliance is imminent. Indeed, Chamisa’s campaign prior to the poll was largely based on discrediting the election outcome. His mechanism of doing so was to attack the credibility of the ZEC. This set the scene to go to the courts on grounds of irregularity in the expected event of a Mnangagwa victory.

To this end, the MDC Alliance on 8 August confirmed that it had drafted its intended court challenge against the outcome of the elections. The group now has until 10 August to file a petition to the Constitutional Court, which must rule on the matter within 14 days. Prevailing circumstances suggest that the MDC may wait until the 10 August deadline, in a bid to delay President Emmerson Mnangagwa’s inauguration — scheduled for 12 August.

The opposition’s case will remain against the ZEC and rest on the issue of some polling stations not publishing results, as well as the two core concerns that Chamisa raised in the lead-up to the elections. These are a lack of transparency in the printing, storage and distribution of ballot papers, and perceived irregularities pertaining to the voters’ roll.

Given the political sensitivity of a court application, a swift ruling is expected. Although there is some basis to Chamisa’s claims — particularly with regards to the voters’ roll — sufficient evidence of irregularity on the part of the ZEC is absent. A ruling in favour of Chamisa’s application to overturn the election results is highly unlikely.

It is perhaps with this in mind that Chamisa has also set the scene for protests against the election outcome. Partly, such events will indicate the relevance of the opposition support base to the judiciary. Moreover, they may be aimed at fomenting enough disruption to allow Chamisa to secure concessions from the victorious Zanu-PF government.

To do this, such post-election rallies will need to be large-scale, widespread and — ideally — disruptive. While the unrest on 01 August may suggest that this could be the case, there are important factors to take into consideration. First, that unrest was focused on central Harare around politically sensitive sites; unrest contagion in the coming days is not anticipated. Second, the violent suppression of the demonstrations will likely serve to discourage all but hardline opposition supporters. Third, the election process has been rubberstamped as generally free and fair by most electoral observers, with criticisms regarding the process more directed to the pre-ballot political environment. These factors, taken together, are likely behind the lack of opposition demonstrations since the 3 August announcement of final results.

The concession that Chamisa may be looking for is the establishment of a Government of National Unity (GNU). Precedent for this was the coalition government that was formed in 2009 through a negotiation process that followed a disputed 2008 presidential ballot. The GNU of that era had President Robert Mugabe of Zanu-PF lead an administration with the MDC-T’s Morgan Tsvangirai as prime minister, and ministerial portfolios shared between Zanu-PF, MDC-T and MDC-M.

Having lost the presidential election — and with an expectation of losing the subsequent court challenge — the next best position for the main opposition coalition may be to seek a GNU and thus an ongoing role in the executive decision-making structures in Zimbabwe.

However, in recent days, President Mnangagwa has publicly ruled out this option. He argued that it is unclear why this is necessity given the ‘free and fair’ electoral outcome. Chamisa has also (at least publicly) dismissed the viability of this, which leaves the ongoing electoral appeal and both formal and informal political measures as alternatives. Rather, Mnangagwa may make a magnanimous play and promise some cabinet positions to the opposition; this may not placate Chamisa entirely, but it will be a meaningful compromise that would also aid in reinforcing his position as a political reformer.

Interestingly, Chamisa’s tactics are almost a carbon copy of those employed by Raila Odinga during last year’s drama-fueled Kenyan election. As opposition leader, Odinga refused to accept the outcome of the ballot and spent the build up to the poll casting aspersions on the role of the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) in Kenya. With this narrative being pushed intensely and effectively in an already polarised environment, it created severe doubts around the legitimacy of the entire process even before a single vote was cast.

In Zimbabwe, the opposition will challenge the election results through legal channels. However, unlike the case in Kenya where the Supreme Court annulled the result of the Presidential poll, the MDC Alliance’s application is expected to be rejected on account of a thin case and a judiciary that is sympathetic to Zanu-PF. Similarly, while street protests may result in temporary disruptions, these are unlikely to gather sufficient momentum to be systemically destabilising in nature.

Realistically, Chamisa’s tactics are designed to extract concessions. Noting the urgent need for Mnangagwa to imbue legitimacy from this election, Chamisa’s hardball tactics could help deliver more favourable terms for both himself and the MDC Alliance constituents, as outlined above. Already, Mnangagwa has adopted a conciliatory approach towards the situation and urged Chamisa to work with him to restore peace and unity. This mirrors the rapprochement that eventually followed in Kenya, where a truce between political adversaries Uhuru Kenyatta and Odinga was reached after months of wrangling and political mudslinging. It would hardly be surprising if the political gridlock in Zimbabwe followed a similar trajectory.

For Zimbabwe’s economy, there is little time to waste and major stakeholders will be keen to avoid the damaging period of uncertainty, inertia and anxiety which followed the Kenyan poll. Indeed, Mnangagwa will want to draw a line beneath this event and focus his administration’s attention on the economy. As a pre-requisite, this will require the normalisation of the political environment and bringing Chamisa and the MDC Alliance into the fold — ideally sooner rather than later.

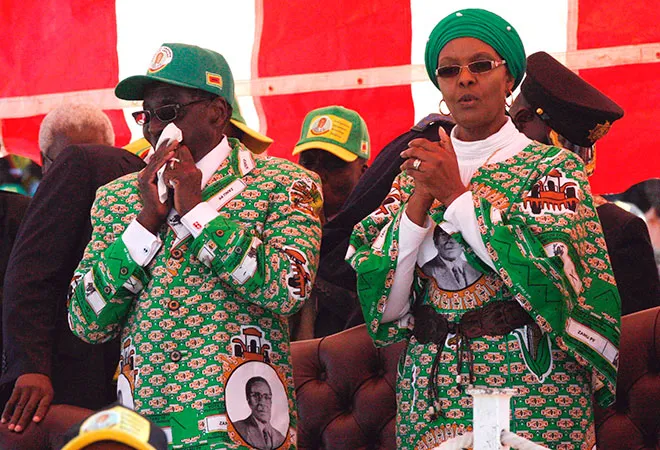

These elections, the first since 1980 without Robert Mugabe contesting the ballot, were meant to provide an opportunity for Mnangagwa to draw a clean break from the Mugabe era and the military sponsored coup which ushered him into power. A changing of guard from a military to a civilian government and the adoption of a more democratic path was meant to create the necessary legitimacy in the eyes of the international community to catalyse dormant investment.

However, heavy handed events in the post-election period have complicated this outlook and have cast doubt on whether the “new Zimbabwe” is actually any different from its previous iteration. Yet, despite the somewhat troubled election, Mnangagwa has effectively been granted a democratic mandate by Zimbabweans and the international community. Impressions of the regime will likely improve once the post-election politicking dies down. At that point, attention will need to shift to the urgent task of repairing the country’s dysfunctional economy, the continuation of the nascent reform agenda and reintegration into the global political economy.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Ronak Gopaldas is director at Signal Risk an African risk advisory firm. His work focuses on the intersection of politics economics and business on the ...

Read More +