This is the sixty fourth part in the series

This is the sixty fourth part in the series The China Chronicles.

Read all the articles here.

The Silk Road calls to mind an image of the distant past, where traders traversed the vast expanse of Eurasia in pursuit of silk, spices and various other commodities. Today, China is attempting to revive these once forgotten routes as part of Xi Jinping’s signature Belt and Road Initiative (一带一路倡议: BRI). However, while much ink has been spilled on the subject of China’s growing network of port, pipeline, rail, and road infrastructure projects, there is one overlooked component of the BRI that deserves greater attention: the Digital Silk Road (数字丝绸之路).

This article examines the origins of this lesser known road, its gradual inclusion into the mainstream Belt and Road discourse, and the underlying forces pushing Beijing to promote greater digital connectivity.

The broad policy outline for today’s Digital Silk Road can be traced to a joint white paper released in 2015 by China’s National Development and Reform Commission, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and Ministry of Commerce. The white paper notes:

should jointly advance the construction of cross-border optical cables and other communications trunk line networks, improve international communications connectivity, and create an information Silk Road. We should build bilateral cross-border optical cable networks at a quicker pace, plan transcontinental submarine optical cable projects, and improve spatial (satellite) information passageways to expand information exchanges and cooperation.

Moreover, in 2016, China’s State Council issued the “13th Five Year Plan, which dedicates a specific section on improving internet and telecommunications links across BRI countries. In particular, the five year plan emphasizes the creation of land and sea cable infrastructure, an Internet Silk Road between China and Arab States, and the creation of a China-ASEAN information harbor.

The concept soon became part of China’s mainstream discourse on the Belt and Road and has been promoted at key international gatherings such as the first Belt and Road Forum, the 4th World Internet Conference at Wuzhen, and more recently, during the 8th Ministerial meeting of China-Arab States cooperation Forum (CASCF), where Xi Jinping extended the scope of the BRI to outer space when he called for the creation of a “Space and Information Corridor”.

All of these various monikers for greater digital connectivity have become what is known today as the Digital Silk Road.

The rise of this new third road, however, begs a simple question: what are the forces that are pushing China to expand its digital footprint?

Confronted with slower growth rates, industrial overcapacity, and an ageing society, China is placing its bets on the future of the digital economy to sustain stable levels of growth. By investing financial resources into ambitious national initiatives such as “Made in China 2025” and Internet Plus, China not only wants to technologically upgrade and digitize its economic base, but also deploy “national players” in telecommunications, e-commerce, and information technology to secure access to untapped markets abroad – and there is no better way to achieve this objective than to marry state-led infrastructure development projects with digital connectivity.

Furthermore, as China’s digital economy matures, domestic firms are not only facing stiffer competition, but also witnessing a decline in domestic demand. As such, these companies have a strong interest in pushing the Digital Silk Road agenda not only because it provides them with an expedient means to venture out to new markets, but also because they see themselves as the largest beneficiaries. As Hong Shen points out:

Given that many BRI projects are directly funded by Beijing-backed financial institutions that often explicitly or implicitly require receiving countries to outsource projects to Chinese companies, China-based Internet firms see the digital Silk Road as an opportunity to seek state largesse and political support for their own decapacity needs. For example, in 2015, China Development Bank and Industrial and Commercial Bank of China issued a $2.5 billion credit line to Bharti Airtel, the largest telecom operator in India, for its domestic infrastructure projects. Bharti Airtel then outsourced part of its network equipment to Huawei and ZTE, boosting the external markets of the two Chinese equipment makers.

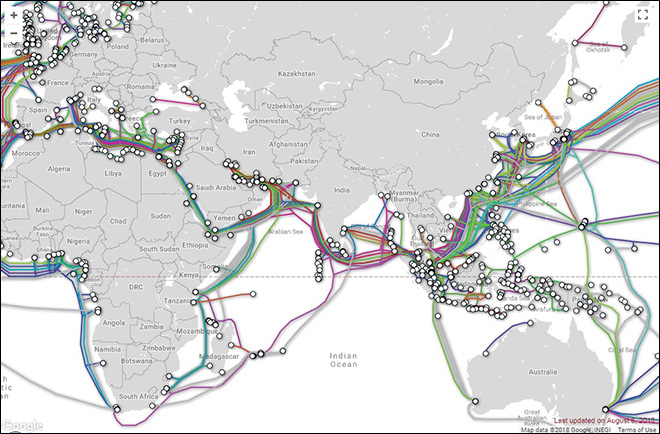

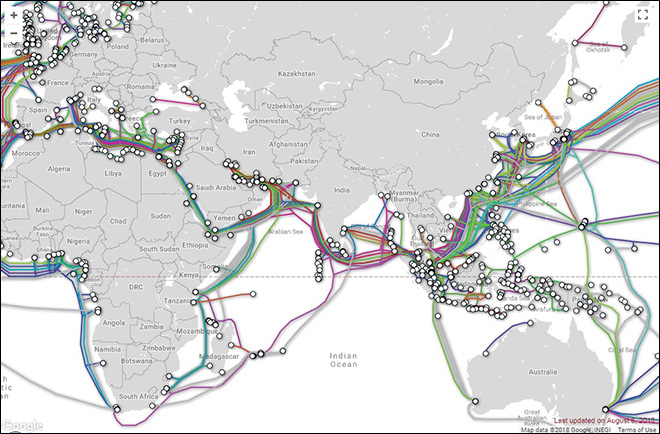

Lastly, there is a strategic dimension to the Digital Silk Road. The lifelines of the modern digital economy are undersea fiber-optic cables, which according to estimates carry more than 98 percent of international internet, data, and telephone traffic. However, the bulk of these cables are both geographically concentrated and largely dominated by US power, which has raised concerns in Beijing about data security. Therefore, Beijing’s push to build cross border and undersea cables, such as the Pakistan-China Fiber Optic Project, is motivated by a desire to circumvent heavily trafficked choke points such as the Straits of Malacca, and to shield its communications from foreign intelligence agencies.

Source: TeleGeography

Source: TeleGeography

Another illustrative example is China’s promotion of its indigenous Global Navigation Satellite System, the BeiDou Navigation System (BDS). BeiDou is one of four major global navigation satellite systems (GNSS) in the world, along with the US Global Positioning System (GPS), European Union's GALILEO and Russia's Global Navigation Satellite System (GLONASS). As part of the Digital Silk Road, China aims to extend coverage of its home-grown satellite-navigation system to the 60-plus countries along the belt and road. By 2020, China hopes to achieve global coverage with a constellation of 35 satellites – allowing China to end its reliance on US GPS; increase its diplomatic clout in regional and international forums on Position, Navigation, and Timing (PNT) related affairs; and provide the People’s Liberation Army’s sensor-equipped platforms and missiles with enhanced guidance capabilities.

In sum, while the advent of the Digital Silk Road presents opportunities and challenges for China and BRI countries, its ongoing development will undoubtedly raise important questions about the future of the global digital order.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

This is the sixty fourth part in the series The China Chronicles.

Read all the articles

This is the sixty fourth part in the series The China Chronicles.

Read all the articles  Source:

Source:  PREV

PREV