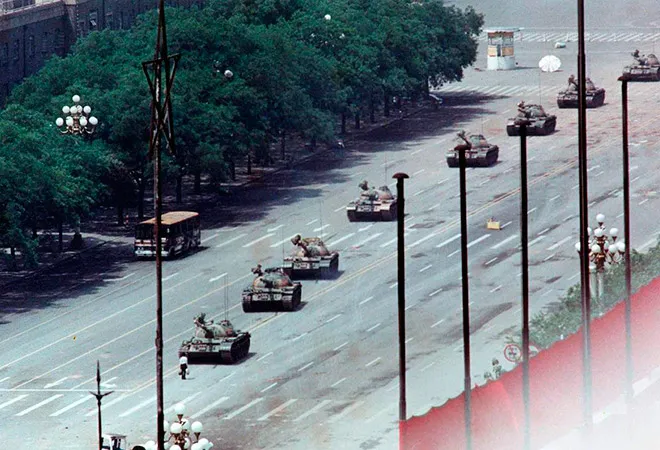

On the night of 3 June 1989, soldiers of the People’s Liberation Army moved in, with tanks, into the historic Tiananmen Square in central Beijing to quell pro-democracy protests. The number of protesters — led by students, but including citizens from all walks of life — had been growing over the weeks and had swelled to about a million. By next morning, the troops had killed hundreds, possibly thousands, of unarmed protesters and bystanders. The exact number of the dead will remain unknown — the Chinese government has never revealed any figures, though independent estimates put the number at between 3,000 and 4,000.

The process of economic liberalisation begun by “paramount leader” Deng Xiaoping in 1978 had also led to an opening up of minds, especially among the youth, who had started demanding a crackdown on corruption, greater political participation, freedom of the press and freedom of speech. The Tiananmen massacre marked an ideological moment of reckoning for the Chinese Communist Party. The liberals were swiftly ousted, and expurgated from history. Economic reforms were halted, but started again in 1992. But political liberalisation would never again be in on the agenda.

As we look at China today, under president-for-life Xi Jinping, we realise that the Party never recovered from that paranoia; indeed that fear psychosis now is its very bone marrow.

China has never allowed any acts of remembrance of 4 June 1989. All references to the event have been systematically excised from all media, history books, discourse. A 2019 University of Toronto and University of Hong Kong study found that at least 3,237 key words referencing the massacre are censored in the country. Any mention of the uprising, however indirect, has led to punitive action. On 1 June this year, at the Shangri-La regional security forum at Singapore, Chinese Defence Minister Wei Fenghe found himself unable to avoid the Tiananmen topic, since a reporter asked a question about it. He defended the government-of-the-day’s actions as “the correct policy”, and said that it ensured that “China has enjoyed stability and development.”

Recently published transcripts of the discussions at a Party Politburo meeting soon after the massacre reveal a deep paranoia about domestic and international forces conspiring to destabilise China and establish a “capitalist dictatorship.” As we look at China today, under president-for-life Xi Jinping, we realise that the Party never recovered from that paranoia; indeed that fear psychosis now is its very bone marrow.

Ever since Tiananmen, the men who rule China have been obsessed with “stability.” Photo: Kevin Frayer/Getty Images

Ever since Tiananmen, the men who rule China have been obsessed with “stability.” Photo: Kevin Frayer/Getty Images

Xi is the most unchallenged and powerful leader of China since Mao Zedong. Even the mildest hint of political dissent is pulverised instantly. He has used technology to create the greatest surveillance state in history. Information from over 200 million surveillance cameras with the world’s most advanced facial recognition software, along with data from gigantic databases of transactions of all imaginable types are being used to create the country’s social credit system, due for national rollout in 2020, which will evaluate people’s political and economic trustworthiness and reward and punish them accordingly. The system is already up and running in many parts of the country.

He has used technology to create the greatest surveillance state in history. Information from over 200 million surveillance cameras with the world’s most advanced facial recognition software, along with data from gigantic databases of transactions of all imaginable types are being used to create the country’s social credit system, due for national rollout in 2020, which will evaluate people’s political and economic trustworthiness and reward and punish them accordingly.

And “untrustworthy" behaviour hardly stops at political dissent, however mild or unintentional. It includes jaywalking, smoking in non-smoking areas, playing too many video games, not walking your dog on a leash or letting it bark too much. Punishments range from travel bans, no bank loans, job loss, denying your children a good education, and being publicly shamed as a bad citizen by having your face and name plastered on billboards. According to a State Council policy document: “If trust is broken in one place, restrictions are imposed everywhere.” It is only a matter of time before the Chinese start getting judged right from their pre-school days up to their deaths. The ongoing horrific repression of the Uighur community in Xinjiang in north-western China is too well-known to be elaborated on here.

Ever since Tiananmen, the men who rule China have been obsessed with “stability.” “A single spark can start a prairie fire,” goes a Chinese saying, and for the last 30 years, the Communist Party has been looking out for sparks and stamping them out, even if it means “chopping a chicken using the blade for a cow,” as another saying goes. Xi is merely taking the efforts to their logical extreme. The official word is “harmony.” The Chinese state craves for harmony for the people.

In October 2017, at the Communist Party’s 19th Congress, Xi unveiled his 14-point “Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era” (short form: “Xi Jinping Thought”), which was unanimously affirmed as the guiding ideology of the Party. Xi Jinping Thought was then enshrined in the Party’s constitution. Dozens of universities around China have set up research institutes to study “Xi Jinping Thought,” which is now part of the core indoctrination that starts from the school level.

Most of the 14 points seem fairly innocuous and obvious: “Improving people's livelihood and well-being is the primary goal of development,” or “strengthen national security.” But, one, in China, words are just the tip of the iceberg of meaning; and two, Xi Jinping does not currently seem too happy.

The last few years have seen numerous strikes and attempts by workers to form independent trade unions, including in giant corporations like Foxconn and Honda, over wages, pensions and working conditions.

Take the 14th Thought: “Improve party discipline in the Communist Party of China.” In January, Xi suddenly summoned hundreds of officials to Beijing. The Party, he said, faces major risks on all fronts. According to The New York Times, he told the gathering, “The Party is at risk from indolence, incompetence and of becoming divorced from the public.” Paranoia, that can be traced back 30 years.

The second Thought is: “The Communist Party of China should take a people-centric approach for the public interest.” Says the NYT report, “(Xi) demanded stricter controls on the Chinese internet — which is already thoroughly censored — and more indoctrination to ‘ensure that the youth generation become builders and inheritors of socialism.’” Obviously, as Xi’s anxiety increases, citizens will face greater policing, though how that is possible is hard to guess.

One source of Xi’s worry is that labour unrest has been growing in recent times. Workers do not have the right to strike in China, and the only official union organisation is the All-China Federation of Trade Unions — a government body. Workers can file cases through a dispute resolution mechanism. According to government statistics, in 1996, 48,121 labour disputes were accepted for arbitration. By 2015 (the latest year for which I could find figures), the number of cases had risen 17 times to 813,859. The last few years have seen numerous strikes and attempts by workers to form independent trade unions, including in giant corporations like Foxconn and Honda, over wages, pensions and working conditions. Certainly, one of the causes of labour disquiet is mass downsizing. In December 2018, even state mouthpiece Global Times reported widespread layoffs in the technology sector.

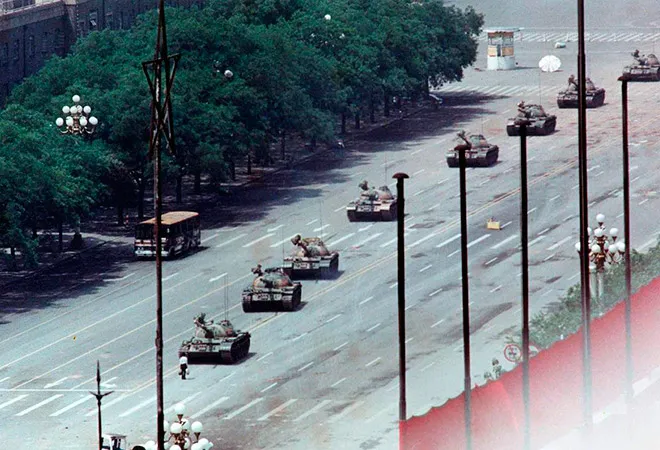

As China has grown more prosperous, and more Chinese have come into contact with the world outside, the burgeoning middle class has become more aware of what freedom means, what rights are. Photo: Anthony Kwan/Getty Images

As China has grown more prosperous, and more Chinese have come into contact with the world outside, the burgeoning middle class has become more aware of what freedom means, what rights are. Photo: Anthony Kwan/Getty Images

The first point of “Xi Jinping Thought” is: “Ensuring Communist Party of China leadership over all forms of work in China.” Companies in China, including foreign firms, are required by law to establish a Party organisation inside them. In August 2017, Reuters reported that many foreign firms operating in China were under political pressure to revise the terms of their joint ventures with state-owned partners to allow the Party final say over business operations and investment decisions — in some cases, firms were being pushed to amend their agreements so that the posts of board chairman and party secretary be held by the same person. Xi’s paranoia is growing, and, defying the laws of physics, as it radiates out, it magnifies.

In fact, the ongoing US-China trade war is showing up many of the weaknesses of the Chinese leadership’s post-Tiananmen strategy. The negotiators may have very little room to manoeuvre, since they have to answer to a despot, and surely no one wants to take the risk of displeasing him. Xi, having established himself as the proto-God of China, cannot afford to lose face in the slightest. Having purged the Party of all voices that could have given him an alternate view, and currently ruling it through fear, he cannot expect any honest discussion of policy, indeed anything other than obsequious agreement with everything he says.

As far as the people of China go, his response has been to get the state-owned media to whip up nationalist sentiment and anti-US outrage. TV channels are showing tacky decades-old films about the Korean War where Chinese actors wearing clunky masks portray American soldiers as monsters. The newspapers are carrying editorials at the rate of almost one per day, vilifying America. But this is a dangerous game to play. It is all very well to rouse patriotic fervour, but at some time the Party also has to contain it, because China will necessarily have to make concessions to the US. And Meng Wanzhou, chief financial officer and heir apparent at Huawei, is not going to be coming home soon. But the Party and especially Xi cannot at any cost appear to be weak to the people. They have effectively boxed themselves in.

If the Communist Party had not crushed all dissent — even the most humble request for openness, in its fear psychosis about real and imaginary enemies lurking everywhere, if it had not thought of itself and its ideology (if it even knows what that is any more) as so fragile that any criticism could cause its surface to crack, it would not have found itself in this position now. The liberals in the Party, who had pushed for talks with the Tiananmen protesters and more inner-party democracy, had not asked for a multi-party system. They had only said that it might be a good idea to listen to outside opinion and not be in denial. They had only said that if the press was given a little bit more freedom, and the courts just a touch of more independence, the Party could look more legitimate in the eyes of the people, which would lead to a happier nation and a more secure regime. But they were overruled, and wiped out.

If the Communist Party had not crushed all dissent — even the most humble request for openness, in its fear psychosis about real and imaginary enemies lurking everywhere, if it had not thought of itself and its ideology (if it even knows what that is any more) as so fragile that any criticism could cause its surface to crack, it would not have found itself in this position now.

In fact, as China has grown more prosperous, and more Chinese have come into contact with the world outside, the burgeoning middle class has become more aware of what freedom means, what rights are. (Traditionally, the Chinese language did not have a word for “rights.” In the 1860s, an American missionary, W.A.P. Martin, translating a book on international law into Chinese, invented a word, chuan li, by combining “power” with “benefits”.) These citizens do not speak, because that is dangerous, but they surely chafe at the bit. The anger keeps on building up inside.

Yes, there will possibly never be another uprising like the one that happened in 1989, but one can see signs of a growing rebellious spirit in the labour unrests, or in the recent widespread outrage by Chinese programmers of Alibaba honcho Jack Ma’s smug assertion that the only formula for success is “996” — working 9 a.m. to 9 p.m., six days a week. Xi sees this subterranean shift, and his response has been to clamp down even harder, ratcheting up repression, hounding and jailing more and more people. Even 30 years after Tiananmen, China’s leadership is unable to understand — or is stubbornly unwilling to understand — the contradiction between economic reform and thought control.

The leaders still seem to believe that some vacuous sentences grandiloquently titled “Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era” will do the trick. But their actions seem to reveal that they themselves do not believe this too much. Tiananmen continues to haunt them.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Ever since Tiananmen, the men who rule China have been obsessed with “stability.” Photo: Kevin Frayer/Getty Images

Ever since Tiananmen, the men who rule China have been obsessed with “stability.” Photo: Kevin Frayer/Getty Images As China has grown more prosperous, and more Chinese have come into contact with the world outside, the burgeoning middle class has become more aware of what freedom means, what rights are. Photo: Anthony Kwan/Getty Images

As China has grown more prosperous, and more Chinese have come into contact with the world outside, the burgeoning middle class has become more aware of what freedom means, what rights are. Photo: Anthony Kwan/Getty Images PREV

PREV