-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

PDF Download

PDF Download

As India welcomed 2021, the country was reporting less than 15,000 new COVID-19 cases per day between mid-January and mid-February. Soon, however, there was a surge, and on 7th April, the number of daily infections reached 126,260 with the seven-day daily average crossing 100,000.[1] By then it was clear, that the second wave of COVID-19 in India would be far more severe than the first one. The steep rise in infections and deaths made headlines across the world, as images of mass pyres and people queueing for free oxygen cylinders in temple grounds made the rounds of social media.

Today, two months later, while the number of active cases has come down in big cities, the pandemic is fast spreading across rural districts, with the biggest increases being recorded in the states of Rajasthan, Maharashtra, Uttar Pradesh, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, and Kerala (See Figure 1). A report by the State Bank of India (SBI) noted that by mid-May, the rural districts accounted for 50 percent of all new cases in the country.[2] The rural areas of Amravati in Maharashtra are worst affected with a large number of new cases,[3] and those of Nagpur in the same state have also become hotspots. About 35 percent of all COVID-19 deaths in Haryana have been reported from the rural districts, with the heaviest toll in Hisar (258), followed by Bhiwani (217), Fatehabad (159), and Karnal (150).[4] The second wave has also hit the rural areas of Gujarat.[5] The state reported 90 deaths in 20 days from one village alone, Chogath, which has a population of 13,000. Two of India’s largest and most populous states – Uttar Pradesh and Bihar—have also witnessed a steep rise in COVID-19 cases in their rural districts.[a]

To be sure, the actual numbers of COVID-19 cases in the rural regions of India could be much higher than the official figures because of low testing rates[6] and people’s reluctance to get tested,[7] to begin with. Given the severe shortage of medical facilities in rural India, managing the spread of the pandemic would prove to be even more difficult than what the urban cities experienced earlier this year.

Figure 1: COVID-19 case trends in urban and rural areas

Figure 2 shows that by the peak of the first wave around September 2020, rural areas accounted for one in every three (33 percent) of all new cases. It was about 65 percent in both rural and semi-rural districts, which is almost double the 34-percent share of urban and semi-urban.

Figure 2: Covid-19 cases in Urban, Semi-Urban, Rural and Semi-Rural Areas

Figure 3: Vaccine doses administered per 100 persons in Urban, Semi-Urban, Rural and Semi-Rural Areas (2021)

At the same time, the vaccination drive has been slow in the rural areas as compared to urban (See Figure 3). The key reasons for this include lack of internet connectivity, low smartphone access, digital illiteracy, and apprehensions about vaccine safety.[11] Moreover, there is also a problem of availability of doses, which has compounded the lag.[12] A December 2020 household survey across 60 districts in 16 states found low preference for vaccines, with only 44 percent willing to pay for it.[13]

Given that 65.5 percent of India’s entire population is rural,[14] adequate steps need to be undertaken at the earliest to prevent the occurrence of a health catastrophe in rural India. An economic crisis is making the challenges more acute. As a response to the rise in infections, many states such as Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh are under lockdowns to curb the spread of the virus. Consequently, villagers who are mostly daily-wage workers or street vendors in nearby towns have lost their livelihoods. While remittances from family members working in big cities were relied upon to boost the incomes of the rural households, the rise in cases in the urban areas beginning in early February led to another exodus of migrant workers from those cities, similar to what occurred in 2020 during the first wave and nationwide lockdown. Rural households suffered losses in household incomes as a result, pushing many to deeper indebtedness and worse hunger. Media reports suggest that people in rural India are eating less and often not able to afford nutritious food like pulses and vegetables.[15] Overall, a survey in October 2020 among urban and rural communities in 11 states found that almost 70 percent of households are not consuming nutritious meals, with about half of them skipping at least one meal every day.[16] If India is to prevent a humanitarian disaster in its hinterland, there is a need for an effective strategy to control the spread of the virus, as well as sincere and targeted efforts to reboot the rural economy and provide welfare services to the people.

This special report describes the specific challenges wrought by COVID-19 in India’s rural areas, and outlines a ten-point agenda for effective pandemic management and the revival of the rural economy. The rest of the report provides an overview of the government’s efforts to manage COVID-19 in rural areas; discusses the specific challenges in those regions; and presents a ten-point strategy for immediate action. Among others, the report recommends the constitution of a task force, and the provision of a special economic package for the rural regions.

The central government in May 2021 released the Standard Operating Practices (SOP) on COVID-19 management in peri-urban, rural, and tribal areas.[17],[18] The blueprint tasked the state health secretaries to oversee the implementation of the SOPs at the grassroots level. The following are the key actions listed in the strategy:

India’s rural health infrastructure has improved since the implementation of the National Rural Health Mission and the Ayushman Bharat Programme in 2018. However, it remains ill-equipped to tackle the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic. Rural India has historically had less access to health services. (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4: Basic Health Infrastructure in Rural India

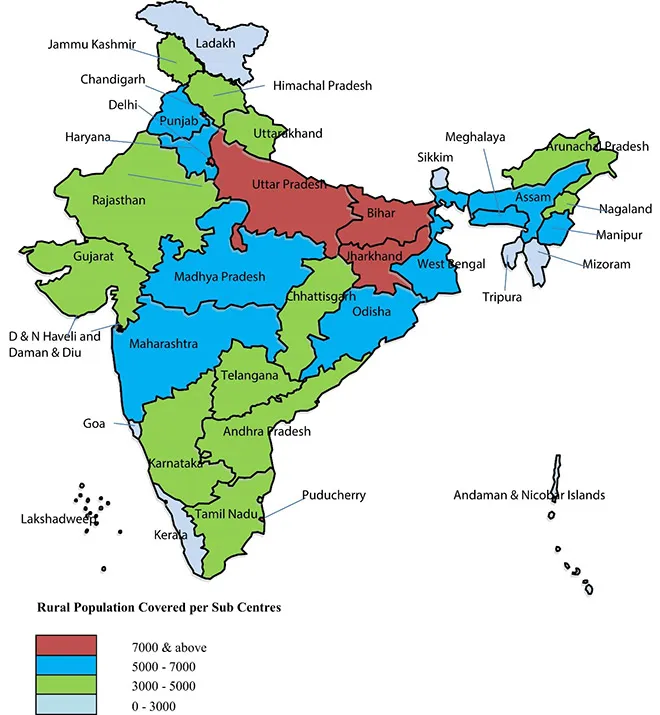

Health facilities in the rural districts are overwhelmed, even without a pandemic. According to Rural Health Statistics 2019-20, the average population covered by a Sub-Centre health facility in the rural areas is 5,729, as against the norm of 5,000; for Primary Health Centres (PHC), it is 35,730, while the norm is 30,000; and for Community Health Centres (CHC), it is 171,779 against the norm of 120,000.[23] There are considerable differences among the states. (See Figures 5, 6, and 7) Both the PHCs and the Sub-Centres are already overwhelmed in several states such as Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, and Maharashtra; the steep rise in COVID-19 cases is compounding the burden.

Figure 5: Average Rural Population covered per Sub Centre in 2020

Figure 6: Average Rural Population covered per Primary Health Centre in 2020

Figure 7: Average Rural Population covered per Community Health Centre in 2020

The Sub-Centres, Primary Health Centres, and Community Health Centres in rural India often lack diagnostic equipment and medicines.[27] Media reports on Bihar, for example, have noted the absence of ambulances in the health centres, forcing many patients to walk long distances to access test kits and basic medicines like paracetamol.[28]

Technology can bring improvements to the current healthcare system, especially in the rural areas. Enduring challenges remain, however, such as lack of connectivity and infrastructure, and of smartphones. Although developing robust IT systems has been one of the objectives of the Ayushman Bharat Programme, not all ASHAs have access to smartphones nor are all Sub-Centres equipped with computers. Overall, rural populations still rely on basic mobile phones, being without means to purchase smartphones. Therefore, central government efforts, such as the Health Ministry’s guidelines regarding tele-consultation with specialist doctors—will likely fail in rural India.

India’s rural districts suffer from shortages in qualified medical personnel. The system rests on the ASHAs, who act both as providers and facilitators of medical care. India’s 1.3-million-strong army of female health activists (Anganwadi Workers[c]) have played a crucial role in managing the COVID-19 pandemic, conducting contact-tracing and engaging in sensitisation campaigns among the population. However, according to a survey by Oxfam,[29] over a quarter of the ASHAs have not received either protective gear (masks and gloves) or their monthly stipends.

There is a critical shortage of medical doctors, paramedical staff, and health workers/Auxiliary Nurse Midwives in large parts of the country. According to Rural Health Statistics 2019-2020, 14.1 percent of the sanctioned posts of Health Workers (Female)/ Auxiliary Nurse Midwives[d] and 37 percent of the sanctioned posts of Health Workers (Male) are currently vacant in the Sub-Centres. Further, there is a shortage of doctors (1,704 positions) in primary health centres across the rural areas, as well as nursing staff (5,772), female health workers (5,066), pharmacists (6,240), and laboratory technicians (12,098) (see Figure 8).

Figure 8: Human Resources in Rural Primary Health Centres

A similar situation prevails in the CHCs which are designed to provide specialised medical care including surgeries. They are operational with about 24 percent of required specialist doctors (See Figure 9). States like Odisha, Chattisgarh, Rajasthan, Karnataka, and Uttar Pradesh face some of the most severe shortages of doctors, medical officers, and nursing staff.

Figure 9: Human Resources in Rural Community Health Centres

The District Hospitals are experiencing the same problems. As Table 1 shows, the number of doctors and paramedical staff has increased only marginally since the launch of the Ayushman Bharat programme a few years ago. Since the initial onslaught of the pandemic, there has been a drastic reduction in the number of doctors at district hospitals (from 24,676 to 22,827) as well as paramedical staff (from 85,194 to 80,920).

Table 1: Number of doctors and paramedical staff in district hospitals in India

The last decade saw some degree of public investments in the country’s tertiary healthcare sector, in particular, in the supply of health workforce: between 2014 and 2019, there has been a 47-percent increase in the number of government medical colleges, compared to a 33-percent increase in private medical colleges. The number of undergraduate medical seats has seen a jump of 48 percent, from 54,348 in the academic year 2014-15 to 80,312 in 2019-20. While India was expanding the number of seats in government medical colleges, it was also leveraging the private sector to fill gaps in personnel and healthcare delivery. However, these tertiary hospitals are almost exclusively located in the urban areas.

The imperative is for financial resources to be pumped into the system through investments in the National Rural Health Mission (NRHM), so that staff shortages are addressed. Unfortunately, no such improvement is being seen in the funding towards the National Health Mission (NHM), which houses NRHM, despite the government’s own National Health Policy 2017 declaring that government expenditure in health will reach 2.5 percent of GDP by 2025. Indeed, analysts note a widening gap between required and actual central funding.[33] (See Figure 10)

Figure 10: India’s Path to 2.5% of GDP on health

Infrastructure creation and upgrade in rural areas also stagnated in the very same states with the most acute needs. For example, analysis has shown that that the pace of upgrade of health facilities into Health and Wellness Centres (HWCs) under Ayushman Bharat has been slower than planned, and a high number of functional HWCs are concentrated in the states with relatively better resources. High-Focus States[e]—i.e., Bihar, Rajasthan, Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha, Jharkhand, Uttar Pradesh, and Uttarakhand, who together account for around half of India’s population—have disproportionately low numbers of HWCs.[34] The 2021 budget did not veer from the same trajectory, despite some stop-gap funding necessitated by the pandemic. Between the estimates of Budget 2020 and those of Budget 2021, there was a paltry increase of 10.5 percent, when the requirements on the ground are far higher. The amount allocated in 2021 — INR 746,020 million — was in fact 10-percent lower than the revised estimates from the previous year, which was INR 824,450 million.[35]

Understandably, India languishes at the bottom of the BRICS countries[f] in terms of government investments in healthcare (See Figure 11). India is indeed the poorest in the grouping as measured in per-capita incomes. Nonetheless, there was a notable lack of any considerable improvement over the past two decades—a period of relatively high economic growth for the country. India’s general government expenditure on health as a percentage of GDP is lower than many countries with lower per capita incomes (see Figure 12). Even smaller neighbouring countries like Nepal, or African countries that receive development assistance from India, spend more resources on public health.

Figure 11: Domestic general government expenditure (% of GDP) in BRICS countries

Figure 12: Countries with lower per capita incomes than India but higher spending on health as a percentage of GDP

Efficient data collection and data-sharing are critical components of any effective COVID-19 management strategy, whether for urban or rural regions. Health experts have often asserted that data should inform and drive India’s COVID-19 management strategies and patient care, rather than guidelines developed in other countries because the conditions in the country are different. Similarly, the template for the rural areas should not be a replica of that for urban regions, because their conditions may be unique to those populations and geographies.

Given the severe shortage in testing capabilities and poor data collection, an accurate picture of the spread of COVID-19 in rural areas remains absent. Deaths are also being undercounted in villages. Most deaths are not registered in rural India and it is easier to bury the dead in fields and open areas.[38] Without reliable data, policies to curb the spread of the virus and treatment of afflicted persons will be even more challenging.

According to noted epidemiologist and Director of the Centre for Global Health Research, Prabhat Jha, better death data is crucial in effective management of the pandemic because it helps in identifying the hotspots.[39] He recommends conducting a Sample Registration System by the Registrar General of India to obtain more accurate death statistics in rural areas—this would involve getting municipalities to release daily or weekly death figures, and mapping hotspots. The sample registration system involves sending teams to a random sample of villages across the country to ask every family if there has been a birth or a death in the past certain number of months. If anyone has died in the family, then they are asked to fill in a form to give details. Data derived from the registration can serve as proxy for the actual number of deaths in the region, and how many of them were Covid-related.

As discussed briefly earlier, significant proportions of the country’s village populations have lost their livelihoods due to the pandemic; many have been pushed to worse states of indebtedness. Economist Pronab Sen predicts that unlike in 2020, when rural India was the “bright spot” in the national economy, these regions are going to be badly affected in 2021.[40] If farmers are not able to access the markets due to either fear of getting infected, or a lockdown, then rural incomes would fall significantly even with a productive harvest. Moreover, non-agriculture services account for about 60 percent of rural incomes, and a fierce spread of the virus—and, as a potential response, lockdowns—will adversely affect the service sector. India saw this in 2020, when the lockdowns that were implemented to arrest the initial onslaught of the pandemic threw the economy into turmoil.

Families who have no source of income, food or medicines can hardly be expected to strictly follow COVID-19 norms like social distancing, handwashing, and wearing masks. The state has to step in to take care of the needs of its citizens when they lose their livelihoods due to lockdowns and are compelled by restrictions to stay at home. As things are, nutritional services have been disrupted across the country. The 2020-21 Union Budget saw an enhanced allocation of INR 356,000 million for nutrition-related programs and INR 286,000 million allocated for women-related programmes. The government has also announced a relief package of INR 1,740 billion under the Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Yojana for the poorest of the poor.[41] This included the provision of an extra five kilograms of wheat or rice and one kilogram of pulses every month. Several other measures like the ‘One Nation, One Ration Card’ scheme to avail food grains under the National Food Security Act could benefit migrant workers. The Indian government has announced five kilograms of food grains for individuals listed under the National Food Security Act, 2013, through the public distribution system; this is meant to reach 800 million people up to November 2021.[42] These efforts, however, might just prove inadequate given the current hardships that rural India is going through, and the long-term economic fallout of the pandemic. If the past one and a half years of the pandemic has taught anything, it is that lockdowns not only create panic, but also bring disproportionate difficulties for the poor. These restrictions on movement and closure of non-essential services, must be accompanied by schemes such as rations or the setting up of community kitchens.

Even without a health crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic, rural women in India face cascading challenges: lack of education and employment, more hours spent on unpaid domestic work, higher risk of maternal mortality, and domestic violence. Women account for more than 70 percent of agricultural labour force in the country, where there is little pay and social protection, if at all.[43] A mere 27 percent of women have completed 10 or more years of schooling in rural areas as compared to 51 percent in urban.[44] Indeed, even as women play an important role in the rural economy—being farmers, wage earners, and entrepreneurs—they continue to face gender-based discrimination.[45]

Teenage pregnancies, for example, are almost double for rural women (9.2 percent) compared to the incidence among their urban counterparts (5 percent) as per the NFHS 4 (2015-16). These pregnancies occur due to various reasons like poverty, lack of education, and employment opportunities. It contributes to the rise in maternal and child mortality, and intergenerational undernutrition.[46],[47] As the pandemic spreads across the rural areas, the women—already reeling from the consequences of gender-based biases—are bearing a greater burden of the economic fallout. Families find less food to eat, and the women—assigned by societal norms to partake of less in the household’s meagre resources—suffer even more. Before COVID-19, data from 2015-16 has shown the worsening incidence of anaemia in India’s women; the prevalence among rural women (15-49 years old) is more than 50 percent.

Another area of concern in the rural regions is maternal healthcare. Unlike during the first wave of the pandemic, when COVID-19 was mostly “mild” in pregnant women, in the second wave, experts are seeing many pregnant women succumbing to COVID-19 complications. Pregnant women with weaker immune systems developed widespread scarring after getting infected by the virus.[48] In the rural districts, even as maternal mortality has declined in the past decade, it remains high at 143 per 100,000 livebirths.[49] The pandemic has only worsened the situation: media reports suggest that many pregnant women in rural India are opting out of institutional delivery because of fear of having to undergo a COVID-19 test.[50] In the absence of a gendered response to the pandemic, current inequalities faced by rural women will only get exacerbated.

Rural-urban migration in India has a ‘circular character’: migrants do not settle permanently in cities but continue to maintain close links with their villages.[51] In India, large numbers of people who leave the villages in search of livelihoods do not find jobs in the formal sector. In the words of noted scholar, Jan Breman, “The people pushed out of agriculture do not give up the habitat which keeps them embedded in the village of their origin; first and foremost, because they may have been accepted in the urban spaces as temporary workers but not as residents. It means of course that they simply cannot afford to vacate the shelter left behind in the hinterland. This is in addition to the fact that dependent member of the household do not join them on departure.”[52] Circular migrants, a term Breman uses, are poorly paid, have long working hours, lack legal protection and social security benefits, and do not have proper basic shelter. They are forced to return to their villages after periods of casual employment.

During the nationwide lockdown in 2020, many of these migrants failed to find the informal jobs that sustained them in cities and had little choice but to undertake the arduous journey back to their village. A similar exodus, of a smaller magnitude, was observed in February-March 2021. The threat is that as the virus mutates further, migrants could be carriers of deadlier variants in both rural and urban areas. Migrants must therefore be identified as a high-risk group that needs targeted care.

Absent systematic research so far, there is anecdotal evidence of villagers refusing to be tested and turning away health workers. For instance, Pradep Kumar, a doctor in a Primary Health Centre in Katihar, Bihar laments,[53] “We send mobile testing teams in villages but they are not interested. Due to the stigma attached to Covid, most of them hide their symptoms and avoid testing.” Indeed, there is extreme fear and stigma associated with COVID-19—and it might not be peculiar to the rural populations. The excesses witnessed during the national lockdown have also contributed to their fears.[54] Some people are also hiding symptoms out of fear of being shifted to isolation wards. At the same time, home isolation—recommended by the Health Ministry for mild cases of the disease—is extremely difficult. Family size is commonly larger in rural areas and three generations living together is more of the norm. Moreover, rural homes are ill-equipped for following the norms related to home quarantine. Many households do not have a second toilet for COVID-19 patients; they typically have one or two rooms which are used to store grain, while the family members sleep together in one room or angan. This is a theme carefully explained on Twitter by Bhairavi Jani,[55] an entrepreneur who lives in the Himalayan town of Pithoragarh in the state of Uttarakhand. Jani underlines the measures of how ill-equipped the rural healthcare system is and why certain COVID-19 protocols will fail in a village setup. In a series of tweets that have resonated with many on the platform, she calls for creating awareness in the villages to overcome false beliefs, creating isolation centres at panchayat ghar to be managed by ASHAs, and ramping up testing.

Villagers are also falling prey to unqualified medical professionals and unverified information circulating in social media.[56] News reports found people, for example, in rural Madhya Pradesh and Haryana who have had no choice but to approach unqualified medical practitioners: they do not have adequate information with which to make decisions, they fear being sent to isolation wards, there is shortage of medical facilities, and city hospitals are overcrowded.[57] The lack of information relates to vaccination as well—and it is not uncommon to hear of rural villagers resisting government vaccination drives.[58]

As the pandemic’s second wave makes further inroads into India’s hinterland, the country could be looking at the possibility of a disaster similar to what occurred in the urban regions early this year. And because 65.53 percent of the country’s entire population are rural, targeted, comprehensive strategies must be undertaken to prevent such a catastrophe from happening. The situation is already dire, and requires immediate attention: medical infrastructures are weak, there are severe shortages in qualified medical staff, the vaccine rollout is slow, and there is poor adherence to safety protocols. These, coupled with enduring, large-scale poverty and lack of livelihoods—which have existed long before COVID-19.

This special report outlined a ten-point agenda for immediate action in India’s rural districts. Beyond this urgent course of action, however, it is equally important that India turns the crisis into an opportunity to rethink current approaches to development: rather than being urban-centric, India must develop better health and welfare systems in the rural regions and make the countryside more resilient to shocks like COVID-19. The blueprint presented in this report can go a long way in not only addressing the current health crisis in India’s villages, but also in the achievement of cross-cutting sustainable development goals: SDG 1 (no poverty); 2 (zero hunger); 3 (good health and well-being); 5 (gender equality); 8 (decent work and economic growth); and 10 (reduced inequalities).

[a] It was in these areas where photographs emerged of corpses floating in the river Ganga, and mass burial sites along the riverbed.

[b] ASHAs are community health workers instituted by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare in the community to create awareness on health and its social determinants and mobilise the community towards local health planning and increased utilisation and accountability of the existing health services.

[c] Anganwadi workers are community-based frontline workers of the Integrated Child Development Scheme program of the Ministry of Women & Child Development.

[d] ANM is a village-level female health worker.

[e] Due to unacceptably high fertility and mortality indicators, the eight Empowered Action Group (EAG) states (Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha, Rajasthan, Uttarakhand, Uttar Pradesh and Assam), which account for about 48 percent of India’s population, are designated as “High Focus States” by the Government of India.

[f] The emerging economies of Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa.

[g] The concept of collective impact was developed by John Kania and Mark Kramer. Collective impact is the commitment of a group of actors from different sectors to a common agenda for solving a specific social problem, using a structured form of collaboration.

[h] Sakhis – a group of women volunteers trained by Ambuja Cement Foundation in healthcare services

[1] HT Correspondent. ‘As India records 126,260 new Covid-19 cases, curbs in more states’, Hindustan Times, April 8, 2021.

[2] “SBI report emphasises on vaccination, says nearly half of the new cases in rural India”, The Hindu, May 7, 2021.

[3] Aditya Bidwai, “After affecting big cities, Covid-19 is now hitting India’s rural areas hard”, India Today, May 7, 2021.

[4] Vishakha Chaman, “In Haryana, most rural Covid deaths in Hisar”, The Times of India, May 18, 2021.

[5] Gopi Maniar Ghangar, “Second wave hits Gujarat’s rural pockets; village loses 90 people to Covid”, India Today, May 5, 2021.

[6] Mithilesh Dar Dubey, ‘Testing times for rural India as delay in RT-PCR test results may hasten the Covid spread’. GoanConnection, May 5, 2021.

[7] “In rural India, fear of testing and vaccines hampers COVID-19 fight”, Livemint, June 5, 2021.

[8] Atul Thakur, “Proof that COVID is now a rural pandemic in India”, Times of India, May 12, 2021.

[9] Vignesh R, ‘Vaccination in rural India trails urban areas as cases surge’. The Hindu, May 18, 2021.

[10] Vignesh R, ‘Vaccination in rural India trails urban areas as cases surge’

[11] Bhavya & Himanshi, ‘Low smartphone reach coupled with lack of digital literacy hit rural India Covid vaccine drive’. The Economic Times, May 16, 2021.

[12] Pranab M, Harpreet B and Sudhir S, “Covid vaccine a distant reality in rural India, shows app”, The New Indian Express, May 23, 2021.

[13] Mithilesh Dar Dubey, “44% rural citizens willing to pay for corona vaccine; two-third want its price to not exceed Rs 500: Gaon Connection Survey”. GaonConnection, December 23, 2020.

[14] Trading Economics, “India – Rural Population”.

[15] “76% of rural Indians can’t afford a nutritious diet: study”, The Hindu, October 17, 2020.

[16] Debmalya Nandy, “COVID and rural economic distress: Food for all and work for all should be the way forward”, GaonConnection, June 2, 2021.

[17] Sneha Mordani, “Centre gives states blueprint for containment of COVID-19 in rural areas”, India Today, May 17, 2021.

[18] Government of India, Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, SOP on COVID-19 Containment & Management in Peri-urban, Rural & Tribal areas, May 16, 2021.

[19] “Govt issues SOPs to combat Covid in rural areas, focus on awareness, screening, isolation”, India Today, May 16, 2021.

[20] G S Mudur, “Union Health ministry releases guidelines for Covid management in rural areas”, The Telegraph Online, May 17, 2021.

[21] Rina Chandran, “Drones are delivering vaccines to rural communities in India“, World Economic Forum, May 25, 2021.

[22] Government of India, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Statistics Division, Rural Health Statistics 2019-20, (New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Statistics Division, 2020).

[23] Government of India, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Statistics Division, Rural Health Statistics 2019-20

[24] Government of India, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Statistics Division, Rural Health Statistics 2019-20

[25] Government of India, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Statistics Division, Rural Health Statistics 2019-20

[26] Government of India, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Statistics Division, Rural Health Statistics 2019-20

[27] Piyush Srivastava, “Covid: RAT kits sent from UP headquarters turns out to be faulty,” The Telegraph Online, May 15, 2021.

[28] “Bihar struggles to cope with rising COVID-19 cases”, The Hindu, April 16, 2021.

[29] Agrima Raina, “ASHA workers are hailed as Covid warriors but only 62% have gloves, 25% have no masks”, The Print, September 21, 2020.

[30] Government of India, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Statistics Division, Rural Health Statistics 2019-20

[31] Government of India, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Statistics Division, Rural Health Statistics 2019-20

[32] Government of India, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Statistics Division, Rural Health Statistics 2019-20

[33] Oommen C Kurian, “Does budget 2020 provide material support for the ongoing health reforms?”, Observer Research Foundation, February 7, 2020.

[34] Oommen C Kurian, “Does budget 2020 provide material support for the ongoing health reforms?”

[35] Oommen C Kurian, “The war budget: Can the Centre fight a pandemic simply by turning water into wellbeing?”, Observer Research Foundation, February 1, 2021.

[38] Uma Vishnu, “Prabhat Jha: ‘Lack of death data prolongs pandemic… survey villages’”, India Express, May 25, 2021.

[39] Uma Vishnu, “Prabhat Jha: ‘Lack of death data prolongs pandemic… survey villages’”

[40] Asit Ranjan Mishra, “Growth setback likely as rural India begins to reel from COVID-19”, Livemint, May 5, 2021.

[41] Shoba Suri, “Coronavirus pandemic and cyclone will leave many Indians hungry and undernourished”, Observer Research Foundation, July 16, 2020.

[42] Meenakshi Ray, “Free ration to 800 million people till Diwali, announces PM Modi”, Hindustan Times, June 7, 2021.

[43] Government of India, Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Annual Report 2017-18, 2018.

[44] Bharath Kancharla, “NFHS-5: Gender and Urban-Rural divide observed in access to School Education”, Faqtly, December 22, 2020.

[45] Alette van Leur, “Rural women need equality now”, (Speech, New York, March 15, 2018) International Labour Organisation.

[46] Sasmita Jena, “Breaking the shackles of intergenerational malnutrition in Jharkhand”, Welhungerhilfe, March 18, 2019.

[47] Ragini Kulkarni, “Nutritional status of adolescent girls in tribal blocks of Maharashtra”, Indian Journal of Community Medicine 44, no. 3 (2019).

[48] Alia Allana, “Why is Covid killing so many pregnant women in India?”, Deccan Herald, May 24, 2021.

[50] Manav Mander, “Wary of Covid testing, pregnant women in villages avoid hospitals”, The Tribune, June 8.

[51] Arjan de Haan, “Rural-Urban Migration and Poverty: The Case of India”, IDS Bulletin 28 (1997)

[52] Jan Bremen, Outcast Labour in Asia: Circulation and Informalization of the Workforce at the Bottom of the Economy (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2010)

[53] Prasun K Mishra and Aditya Nath Jha, “Covid-19 stigma, vaccine hesitancy slowing fight against covid-19 in rural Bihar”, Hindustan Times, May 20, 2021.

[54] Aarefa Johari and Vijayta Lalwani, “Indians fear lockdowns more than Covid-19. How prepared are governments to avert a crisis this time?”, Scroll.in, June 13, 2021.

[56] Rahul Noronha, “Why unqualified medical practitioners are a hit among Covid patients in rural MP”, India Today, April 29, 2021.

[57] Anurag Dwari, “In Rural Madhya Pradesh, A ‘Field Hospital’ For Covid Run By Quacks”, NDTV, May 6, 2021.

[58] Omar Rashid, “People in some rural areas resisting vaccination, say U.P. officials”, The Hindu, May 25, 2021.

[59] “India 145th among 195 countries in healthcare access, quality”, Economic Times, May 24, 2018.

[60] Nancy Fullman et al., “Measuring performance on the Healthcare Access and Quality Index for 195 countries and territories and selected subnational locations: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016”, The Lancet 391, no. 10136 (2018),

[61] Ashok Kumar E.R, “Why India needs private-public partnership in healthcare”, Business Line, March 18, 2021.

[62] Amarty Sen, “A better society can emerge from the lockdowns”, Financial Times, April 15, 2020.

[63] PTI, “Second wave rendered 1 cr Indians jobless; 97 pc households’ incomes declined in pandemic: CMIE”, Economic Times, May 31, 2021.

[64] Guy Standing, “Support is growing for a universal basic income – and rightly so”, The Conversation, May 26, 2021.

[65] Vignesh Radhakrishnan, “Vaccination in rural India trails urban areas even as cases surge”, The Hindu, May 18, 2021.

[66] Ashna Butani, “Delhi: At bus terminals and railway stations, lab techs, volunteers have hands full as testing ramps up”, The Indian Express, April 4, 2021.

[67] Swaniti Initiative, “Members of Parliament Local Area Development Scheme: Exploring opportunities with emphasis on Jharkhand”.

[68] Kirtika Suneja, “Government allows MPLADS funds to setup oxygen manufacturing plants in govt hospitals”, The Economic Times, April 30, 2021.

[69] Mark R. Kramer and Marc W. Pfitzer, “The Ecosystem of Shared Value”, Harward Business Review, October 2016.

[70] NITI AAyog 2021. ‘Investment opputunities in India’s Healthcare sector’.

[71] Tata Sustainability Group, “TATA Steel MANSI Project”.

[73] Ambuja Cement, “Reaching out to rural India in the fight against Coronavirus”, April 7, 2020.

[74] “Venture capitalist Vinod Khosla pledges $10 million to aid India’s Covid-19 fight”, The Economic Times, May 3. 2021.

[75] “Donors race to aid India during Covid-19 surge”, Deccan Herald, May 6, 2021.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Dr Malancha Chakrabarty is Senior Fellow and Deputy Director (Research) at the Observer Research Foundation where she coordinates the research centre Centre for New Economic ...

Read More +

Dr. Shoba Suri is a Senior Fellow with ORFs Health Initiative. Shoba is a nutritionist with experience in community and clinical research. She has worked on nutrition, ...

Read More +