Maternal nutrition plays a crucial role in optimising pregnancy outcomes and influencing maternal, neonatal and child health outcomes. Maternal undernutrition is estimated to account for 20% of childhood stunting. Poor nutrient intake combined with poor education and low socio-economic status of women adversely impacts behavioural practices pertaining to appropriate self-care that affects body mass index (BMI) of pregnant women and fetal growth and contributes to undernutrition (stunting) in children. The significance of maternal nutrition on child nutrition is well recognised and is an integral part of programmes for preventing child undernutrition directed at the window of opportunity, that is, in the first 1000 days of life.

Women’s poor nutrition, both during adolescence and the pre-conception stage, contributes to a mother entering pregnancy undernourished with serious consequences such as impairment of fetal development resulting in births of babies small for gestational age (SGA) or low birth weights (LBW). Evidence indicates a strong association in improvement in the nutritional status of women (measured as Body Mass index or BMI) 15–49 years with reduced incidence of low birth weight babies. Moreover, it is reported that women who were stunted in childhood remain stunted as adults and also have a high chance of having stunted offspring.

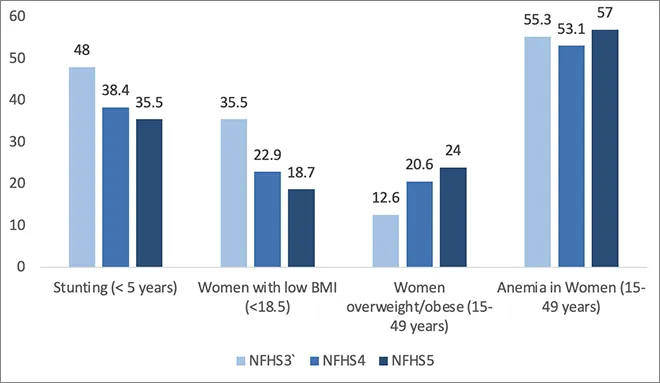

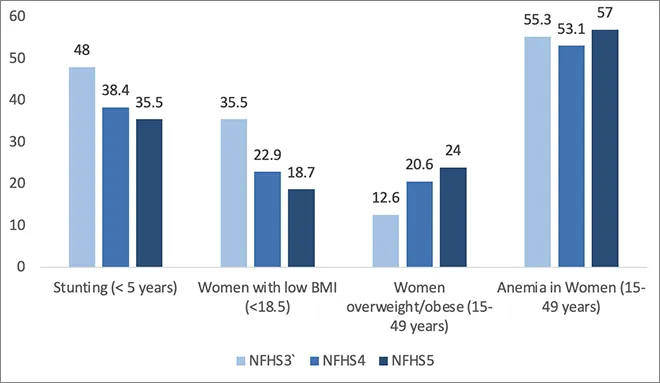

Maternal Malnutrition comprising undernutrition, overweight as well as anaemia adversely impacts pregnancy outcomes. As indicative in fig 1, women undernutrition declined to 18.7 % in 2019-21 from 35.5 % in 2008-9 while overweight/obesity doubled during this period and the prevalence rate of anaemia remained almost stagnant.

The increase in the overweight rate in women in India is attributed to a shift in food eating habits and decreased energy expenditure with a rise in sedentary habits. Ease in the availability of low cost attractively packaged unhealthy processed foods that have a high content of fat and sugar are often consumed by women resulting in excess energy intake against the energy required for daily chores or mobility. Besides undernutrition and overnutrition problems, micronutrient deficiencies are prevalent in women of reproductive age. Data report indicates that women’s diets are poor, and deficiencies of key micronutrients (e.g., iron, folate, vitamins B12) are widely prevalent, irrespective of whether a woman has normal, low, or high BMI. According to NFHS 5, iron and folic acid deficiency anaemia affect 57 percent of women. Prevalence of anaemia in adolescent girls (15-19 years) is also alarming at 59.1 percent in 2019-21 as compared to 54.1 percent in 2015-16. A 2021 study finding reveals poor dietary intake among pregnant women due to poverty, food unavailability, lack of awareness, food taboos and gender bias.

As per a recent report by UNICEF, “Malnutrition in women is rooted in poor care practices at the individual, household, community and societal levels”. Women’s nutrition deserves attention to tackle malnutrition in all forms at all ages and to break its intergenerational cycle. Undernutrition in women is a consequence of poverty and is mediated by socio-cultural norms and inequitable practices that constrain women’s ability to make decisions about their nutrition. Women are neglected when it comes to eating, often eating less and only in the end after the family has consumed the meal. There are gender norms leading to unequal distribution and consumption of food by women in households. A WFP study in Uttar Pradesh reveals that one-fifth of the women surveyed mentioned having consumed less food or reduced portion size owing to economic constraints to buy food. Another study on women from rural India indicates dietary gaps and a lack of diversity in diets consumed by them. A project among tribal communities in Rajasthan shows improvement in women’s nutrition by addressing intra-household food consumption and women’s autonomy.

Women are neglected when it comes to eating, often eating less and only in the end after the family has consumed the meal. There are gender norms leading to unequal distribution and consumption of food by women in households.

Covid has further exacerbated women’s nutrition security and food consumption. Evidence from rural India indicates deterioration in food expenditure and women’s dietary diversity owing to the pandemic-induced economic shock and restricted access to nutritious foods. Assessment of food security among vulnerable groups in Odisha shows poor dietary diversity and food frequency in women-headed households. A review among low-middle income countries, indicates high food insecurity in women from low socioeconomic status. A stark gender disparity has been seen in the prevalence of undernutrition among Indian tribal women.

POSHAN Abhiyaan recognises the significance and stresses on nutrition care across lifecycle. The recently released guidelines of Saksham Anganwadi and POSHAN 2.0 positions nutrition care of adolescent girls high on the agenda for meeting the target of reducing childhood undernutrition. Besides diet and nutrition education, the Scheme for Adolescent Girls aims to mobilise the community to encourage and support girls to complete secondary education and empower them to take decisions on self and family care with informed use of available resources.

It is said that ‘Hunger has a woman’s face’ as in nearly two-thirds of all countries, women face more food insecurity than men. Investing in better nutrition for women is crucial to achieving the Sustainable Development Goal on ending all forms of malnutrition and Global Nutrition Targets on stunting, wasting and LBW. As a priority, there is a need to improve the quantity and nutrient level of food consumed by the household particularly women and children for improved nutritional status. Also empowering women helps in building the human capital and improving the health of future generations.

This commentary originally appeared in News18.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV