The signing of an internal security agreement by India and China last Monday is an indicator of the special nature of their relationship. This features competition, conflict and cooperation. We all know the points of conflict – the disputed 4,000-km border, Pakistan, the Masood Azhar issue, and the question of India’s NSG membership.

Lesser known are areas of cooperation – India’s membership in the Beijing-sponsored Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank, our membership in BRICS, the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO), the Conference on Interaction and Confidence Building Measures in Asia (CICA) and in various international bodies on a range of issues.

China is India’s biggest trading partner and a large market for Chinese products, and Indian retailers are keen to acquire cheap Chinese goods to market.

The New Trend

The new agreement can be seen as part of the new trend in Sino-Indian relations initiated by the Wuhan summit between Prime Minister Modi and President Xi Jinping earlier this year.

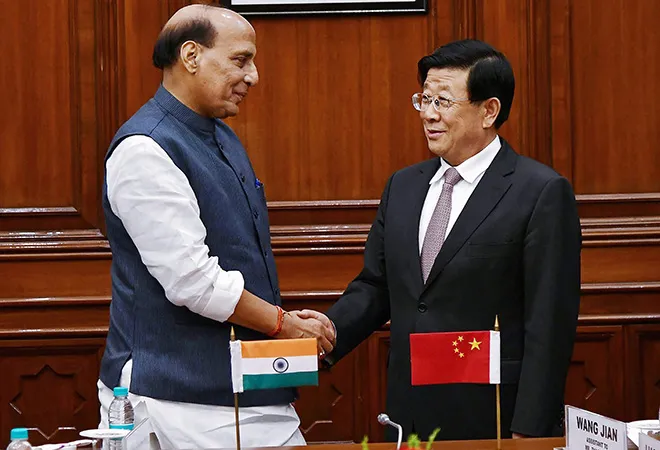

The pact focuses on terrorism, narcotics and human trafficking, intelligence sharing and disaster management. The significance of the agreement is obvious from the fact that the signatory on the Indian side was the Union Home Minister Rajnath Singh, and the Chinese Minister of Public Security Zhao Kezhi.

Zhao is a politician and police officer who was elevated to his current office in the last Communist Party Congress in November 2017. China’s Ministry of Public Security is responsible for the internal security and day-to-day policing of the country.

Negotiations for the agreement began in 2015 following Union Home Minister Rajnath Singh’s visit to China. Initially, the Chinese wanted separate agreements for the different issues, but in the wake of Wuhan, they accepted the idea of an umbrella agreement.

The Wuhan summit itself came after the two-month standoff between the Indian Army and the People’s Liberation Army in the India-China-Bhutan trijunction on Doklam plateau.

Besides Doklam, Sino-Indian relations had been roiled by the Chinese refusal to support India’s candidacy to the Nuclear Supplier’s Group and to put a hold on India’s efforts to have Jaish-e-Muhammad chief Masood Azhar put on a UN list relating to terrorism.

In turn, the Chinese were unhappy over New Delhi using the Tibet card by inviting the head of the Tibetan Central Administration Lobsang Sangay to Prime Minister Modi’s inauguration, and to have a Union Minister welcome the Dalai Lama to Tawang in Arunachal Pradesh.

What Are the Issues?

Having used megaphone diplomacy to assail China for not supporting our NSG or Masood Azhar case, New Delhi is now using an orthodox diplomatic approach to persuade the Chinese of its case. So far, Indian officials say, the Chinese have not budged on these issues. But it is possible that some patient diplomacy will yield results.

China, too, has worries about terrorism, emanating from separatists in Xinjiang. The Chinese are making extraordinary efforts to stamp out Islamist ideas in their western province and are sensitive to the movement of Uighurs around the world.

Recall the episode in 2016 when India granted and later withdrew a visa given to Dolkun Isa, an Uighur activist who was scheduled to attend a conference of Chinese dissidents in Dharamsala, where the Dalai Lama resides. Subsequently, some other Chinese dissidents, too, were denied visas.

Beyond these high-profile issues, the agreement will be of practical use to deal with issues of mutual interest, such as narcotic smuggling, human trafficking, and disaster management.

With the movement of Indians and Chinese in each other’s countries, there are often issues relating to arrests and imprisonment of their respective nationals. The agreement can pave the way for dealing with such issues and lead to the signing of an extradition treaty between the two countries.

A Sidelight of the Meeting

Beyond terrorism, India also wants an agreement to deal with transnational crimes and cyber crimes, and to deal with white-collar criminals, as China has well-known capabilities in the cyber area. The agreement will feature an important component of exchange of information that will help in pre-empting criminal acts. Towards this end, the plan is to set up a 24x7 hotline to facilitate the exchange of information.

The agreement has little to do with the Sino-Indian border dispute, which is handled through other mechanisms and agreements. But it will definitely deal with cross-border infiltration and, more importantly, disaster management. Because rivers flow from China into India, there are often situations where forewarning is vital to prevent casualties from floods or landslides downriver.

An interesting sidelight of the meeting were the activities of Kiren Rijiju, the Minister of State for Home Affairs, who hails from Arunachal Pradesh – a state claimed in its entirety by China.

Rijiju was kept out of the meetings, but called in at the last minute to participate in the formal signing ceremony.

His absence had provoked questions from the media and it is believed that he was told at the last minute to participate in the signing ceremony.

The Wuhan summit has set the tone of the Sino-Indian relations in the current period. It is aimed at getting the two countries to manage the difficult areas of their relationship and find areas of convergence, and also promote better coordination between them. The summit also sends an important signal globally, that the two countries are quite capable of handling their differences through dialogue and discussion.

This commentary originally appeared in The Quint.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV