-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

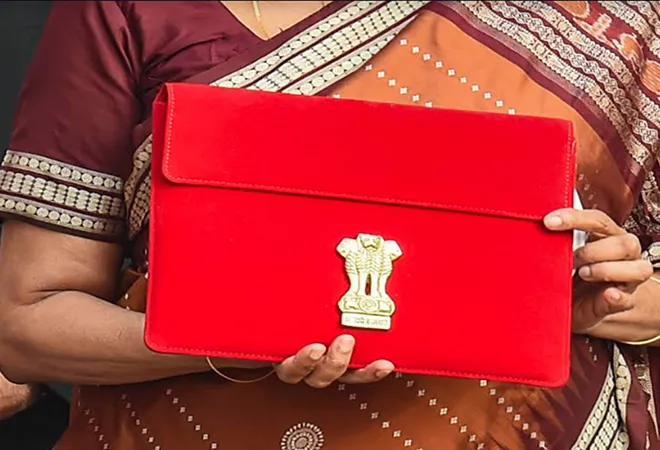

This essay examines the Union Budget 2022 from the perspective of the changing paradigm of development governance as acknowledged globally.

Budget 2022 attempts to recognise the pandemic-induced impact on poverty levels by emphasising a variety of schemes for the poorer classes, such as access to electricity, cooking gas and direct benefit transfers amongst others.Given this background, the Finance Minister talked of addressing efficiency and equity in the same vein: focusing on economic growth at a macro level, and inclusive welfare schemes at the micro level. Budget 2022 attempts to recognise the pandemic-induced impact on poverty levels by emphasising a variety of schemes for the poorer classes, such as access to electricity, cooking gas and direct benefit transfers amongst others. What is noteworthy in this Budget is that the variety of welfare schemes for sustainable economic recovery tries to capture the various capitals (natural capital, physical capital, and human capital) enshrined in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), aimed to be achieved by 2030. This government is not shy of using buzz words in its successive Union Budgets, and this time, the government's priorities are laid down in the context of ‘Amrit Kaal’ (Independent India’s run up to turning 100 years). In fact, this Budget largely finds India’s ‘Amrit Kaal’ in synchronisation with the UN Sustainable Development Agenda 2030. Let us take this up one by one. Firstly, to enhance the human capital aspect of sustainable development, a variety of reforms are suggested in the agricultural sector in order to increase farmers’ income, progressing towards SDG 1 (No Poverty). Additionally, this is probably the first time that mental health (SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being) is prominently highlighted in the Union Budget through the announcement of the National Mental Health Programme - that is expected to benefit India’s huge working-age population continuously shifting gears between ‘work-from-home’ formats and in-person office setups, alongside a variety of mental stresses caused by the pandemic. Other schemes to boost the labour markets include an additional credit of INR 2 trillion for MSEs, focus on increasing skill levels, digitising health and education, etc. Secondly, in terms of physical capital infrastructure, quite a bit of emphasis is laid on improving connectivity, transport and logistics (under the purview of the PM Gati Shakti Scheme) - especially with the announcement of expanding the National Highways Network by 25,000 kilometers in 2022-23 (SDG 9: Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure). This could be regarded as the starting point for policy decisions aiming to ameliorate supply chain disruptions caused by the pandemic, making the domestic economy more resilient in the longer horizon.

Financing this range of schemes would require a range of investments from both public and private sources which has been elaborately laid out in the Budget.Thirdly, the efficient utilization of India’s natural capital finds enough mention through policies announced in terms of energy transition, EVs, etc. In fact, SDG 13 (Climate Action) is significantly considered in this Budget. And finally, financing this range of schemes would require a range of investments from both public and private sources which has been elaborately laid out in the Budget. This would also require mobilising the social capital embodied in the economy, in agreement with SDGs 16 (peace, justice and strong Institutions) and 17 (partnership for the goals). In consonance with our previous research and empirical evidence, which shows that advancing the SDGs will have a direct positive causality on the business climate in the Indian states, the Finance Minister introduced Ease-of-Doing Business 2.0 in conjunction with Ease of Living, to mobilise the various aspects of physical, natural and human capitals. This would be based on the tenets of trust-based governance and the involvement of states keeping up with the spirit of India’s federalist structure; digitisation of processes; removal of barriers to businesses; crowd sourcing of suggestions and analysing ground-level impacts. Additionally, the development of urban centres and reimagining cities as centres of sustainable living is in the same vein as creating financial hubs with congenial business conditions.

The remedial measures for reviving the Indian economy should be focused on policies aimed at demand factors — especially private consumption demand — rather than the supply-side interventions attempted so far.As such, the increasing income inequality in India has led to a faster increase in wealth inequality. While the possession of wealth of the top 1 per cent of the population increased from 16.1 per cent in 1991, the same proportion of the population owned 42.5 per cent of the wealth in 2020. On the other hand, the proportion of wealth of the bottom 50 per cent of the population declined from 12.3 per cent in 1961 to 2.8 per cent in 2020, thereby indicating the increasing divergence in wealth possession between the top and the bottom sections of the population. The income in the hands of the top 1 per cent increased from 10.4 percent of the total in 1991 to 21.7% in 2019, while that of the bottom 50 per cent declined from 22.2 percent to 14.5 percent. In this consumption-driven growth economy, the extra unit of money in the hands of the lower and middle income groups can result in an increase in consumption demand, thereby spurring growth. This necessitates a “Keynesian” response through greater wealth taxation, lowering of the personal income taxes of salaried middle-income groups to increase their disposable incomes, transfers to vulnerable and lower-income groups (through targeted basic income schemes or otherwise) and rationalisation of the GST to compensate for the lost revenues. However, that opportunity is lost, at least for this year. The Budget 2022 also announces the launch of a new Digital Rupee to be issued by the Reserve Bank of India starting 2022-23. Although this is a big jump towards digitising the Indian economy, the relatively sorry state of FinTech literacy, access to smart devices and internet penetration in India might be a major impediment in terms of the number of people, who can benefit from such schemes. It might have little to no effect on people's consumption demand.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Dr Nilanjan Ghosh is Vice President – Development Studies at the Observer Research Foundation (ORF) in India, and is also in charge of the Foundation’s ...

Read More +

Soumya Bhowmick is a Fellow and Lead, World Economies and Sustainability at the Centre for New Economic Diplomacy (CNED) at Observer Research Foundation (ORF). He ...

Read More +