-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

PDF Download

PDF Download

Premesha Saha, “Understanding ASEAN’s Non-Linear Approach to the Russia-Ukraine War,” ORF Issue Brief No. 596, December 2022, Observer Research Foundation.

On 2 March 2022, nine of the 11 Southeast Asian states voted for a United Nations (UN) General Assembly resolution reprimanding Moscow for its invasion of Ukraine a week earlier, and calling for peace.[1] Vietnam and Laos, two historic partners of Russia, abstained. Some days earlier, immediately following the eruption of war, the foreign ministers of the ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) issued an official statement on 26 February 2022. It said ASEAN was “deeply concerned” about the events in Ukraine and called on both sides “to exercise maximum restraint.”[2] It stressed the importance of key principles such as those of “mutual respect for sovereignty”, “territorial integrity”, and “equal rights” of all nations, but did not condemn Russia’s actions.[3]

Since these early, nearly-unanimous public stance, the responses from Southeast Asian governments have been diverse—and, some say, muted.[4] Singapore made the rare decision to impose sanctions on Russia, and Indonesia quickly criticised the actions of Russian President Vladimir Putin. The Philippines, a treaty ally of the United States (US), vacillated and described itself as “neutral”. Meanwhile, Thailand and Malaysia have remained mostly silent.[5]

This brief aims to look at the varied responses of the ASEAN member states and the factors that have influenced such positions. It explores the impacts of these approaches on the principle of ‘ASEAN centrality’, ASEAN’s relations with global powers, and the group’s overall standing in the evolving dynamics of the Indo-Pacific region. It makes a case for a non-linear approach to examining ASEAN’s behaviour in international relations.

Many Southeast Asian countries are dependent on imports of essential commodities. In 2020, for example, ASEAN countries imported 9.7 percent of their fertiliser supply from Russia and 9.2 percent of cereals from Ukraine. These countries have seen shortages in supply in the past 10 months, and their economies have felt the impacts on the provision of basic services such as transport and electricity.[a] According to the World Bank, the conflict will cause global prices of energy and food to rise by 50 percent and 20 percent, respectively, in 2022. The inflation rate for ASEAN as a group increased from 3.1 percent in 2021 to 4.7 percent in 2022.[6]

Rising commodity prices threaten to hinder Southeast Asian countries’ recovery from the pandemic, which in turn can heighten the risk of political and economic instability.[7] Indonesia could be particularly badly hit, with 25 percent of its grain coming from Russia and Ukraine, and 50 percent of its fertiliser sourced from Russia and Belarus. Russian energy firms are also involved in joint ventures in key ASEAN economies, notably Vietnam (Zarubezhneft) and Indonesia (Rosneft).[8]

Politically, the conflict should concern the ASEAN countries as it challenges the key principles of territorial integrity and sovereignty on which the Indo-Pacific rests. At the centre of the Indo-Pacific lies Southeast Asia, and the ASEAN is still regarded as the most credible and only regional architecture of the Indo-Pacific. Many states that have stakes in the region—such as the United States, Japan, Australia, India, and countries of the European Union (EU)—stress on ASEAN centrality and the importance of the group for maintaining peace and stability in the Indo-Pacific.

The reactions so far of specific ASEAN countries can be grouped into three. Singapore, Indonesia, and Brunei condemned Russia’s move immediately after it commenced the invasion, albeit using varying language. Singapore said it “strongly condemns any unprovoked invasion of a sovereign country under any pretext.” In early March, it announced economic sanctions against Russia, banning exports of military-related goods and banking transactions.[9] Indonesia was less direct and condemned “any action that constitutes a violation of the territory and sovereignty of a country”; and Brunei used a formulation similar to Indonesia’s.[10]

The second group—Vietnam, Malaysia, and the Philippines—evinced less strident reactions. Vietnam referred to the United Nations Charter, emphasised the need for “self-restraint” and “dialogue”, but stopped short of condemning Russia’s actions. Malaysia said it hoped for “the best possible peaceful settlement” to the conflict. The Philippines said it was not for Manila to “meddle” in the events in Ukraine.[11] In the last group, Myanmar’s State Administration Council stood alone in supporting Russia’s actions.[b],[12]

Southeast Asian countries were also divided in their voting at the United Nations. On 2 March 2022, an emergency session of the UN General Assembly gathered to vote on a resolution condemning Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Most Southeast Asian countries supported the resolution, of which Singapore, Cambodia and Timor-Leste were co-sponsors. Laos and Vietnam abstained, and Myanmar, which continues to be represented in the UN by its pre-coup civilian government, voted in favour of the resolution. While many countries in the region chose to wield diplomatic language on Russia in their individual statements, they used the UN platform to demonstrate that they would not tolerate forceful violations of national sovereignty and territorial integrity.[13]

In early April, however, only the Philippines, East Timor, and the civilian government of Myanmar voted in favour of a resolution suspending Russia’s eligibility to participate in the UN Human Rights Commission; Laos and Vietnam opposed it; and six countries, including Singapore and Cambodia, abstained. Singapore, which had condemned Russia by name and imposed economic sanctions, explained its abstention by saying that the vote should have waited for the results of an independent investigation into reported human rights violations in Ukraine.[14]

Singapore said it will impose export controls on items that can be used as weapons in Ukraine. It will also block Russian banks and financial transactions connected to Russia. This may yet be the strongest position to have come from among the ASEAN member countries. Emphasising the issue of sovereignty of an independent state, Singapore referred to the “existential crisis” that smaller countries face in the inter-state system.[15]

Indonesia raised the following key points in a press statement released on the same day as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine:[16] It expressed concern about the escalation of the armed conflict on the territory of Ukraine which seriously endangers the safety of the people and has an impact on peace in the region; it affirmed that international law and the UN Charter regarding the territorial integrity of a country are adhered to and condemning any action that clearly constitutes a violation of the territorial integrity and sovereignty of a country; and it called on all UN member states to prioritise negotiations and diplomacy to stop conflicts.

Vietnam, a close ally of Russia’s, expressed “deep concern” with the events in Ukraine. It said it was following “with keen attention” the situation of the Vietnamese community in Ukraine, “and upholds the need to ensure the life, property, and lawful rights and interests of Vietnamese nationals and businesses in this country.”[17]

The Philippines’, through its Defense Secretary Delfin Lorenzana stated, “We are not located beside Ukraine and it’s none of our business to meddle in whatever they’re doing in Europe. The Philippines will stay neutral for now.”[18]

General Zaw Min Tun, a spokesperson for Myanmar’s military council, cited the reasons for the military government’s support of Russia: “No. 1 is that Russia has worked to consolidate its sovereignty. I think this is the right thing to do. No. 2 is to show the world that Russia is a world power.”[19] The government-in-exile, for its part, issued a statement on Twitter in support of Ukraine, condemning the invasion. It said the war “will be a major obstacle to the maintenance of international peace, security, and human development.”[20]

In his remarks at the UN 76th plenary session, Suriya Chinadawongse, Thailand’s representative to the UN, expressed concern over the escalation of tensions in Ukraine. Thailand specifically referred to the Minsk agreement—the ceasefire pact signed in 2015 between Kyiv and Moscow, as well as other UN efforts and regional mechanisms. It also expressed concern at the possible humanitarian consequences of the conflict.”[21] At the same time, Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha said that Thailand would remain “neutral”.[22]

This section attempts to illuminate the reasons why the Southeast Asian countries have responded to the Ukraine conflict in the way that they have so far. The reasons are related to these countries’ specific economic and geopolitical interests, which will be discussed in turn in the following paragraphs.

The ASEAN trade space with Russia has taken a hit in 2022, with sanctions taking a bite out of growth. ASEAN-Russia trade, which grew by 34 percent in 2021 and reached US$20 billion, has historically covered a wide range of commodities.[23]

In June this year, Indonesia’s trade minister, Muhammad Lutfi, followed President Joko Widodo’s instructions to boost trade with the country’s non-traditional partners and visited Russia for bilateral talks as well as a meeting with the Eurasian Economic Union. While Moscow is far from being among Jakarta’s largest trading partners, bilateral trade has grown significantly in recent years.

Indonesia is also keen to attract Russian investments, and the two sides are exploring cooperation on Covid-19 vaccine production. Overall, Russia’s foreign direct investment flows into ASEAN were pegged at US$45 million in 2019, making Russia the 9th largest investor in ASEAN.[24]

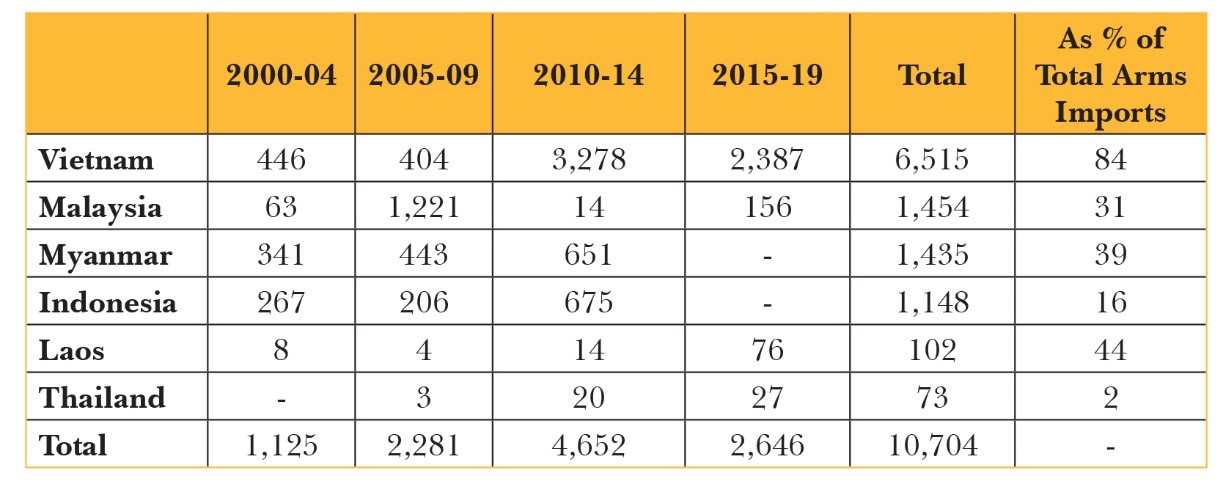

Russia is also an important arms supplier for many of the region’s countries especially Vietnam, Malaysia, Indonesia and Myanmar.[25] Vietnam, in particular, has a decades-old relationship with Russia dating back to the Cold War era. Since 2000, more than 80 percent of Vietnamese military equipment have been provided by Russia, helping its armed forces modernise and increase its capabilities against China in the South China Sea.

Indonesia is another long-standing buyer of defence supplies from Russia, notwithstanding Jakarta’s December 2021 decision to drop Russian Sukhois from its options for acquiring new fighter jets.[26] Defence Minister Prabowo Subianto’s hosting of the first-ever ASEAN–Russia joint maritime exercise in December 2021 in Indonesian waters underscored the government’s interest in consolidating a relationship with a power that has served as an important source of weaponry for Jakarta and many of its ASEAN colleagues.

Moscow also sells weapons to Malaysia, Thailand, and the Philippines, while it is one of the main providers of munitions to the military junta that took power in Myanmar in February 2021.[27] Indeed, Russia is one of the few countries that have defended the military council that seized power in a February 2021 coup and detained de facto leader Aung San Suu Kyi and other high-ranking officials. UN and Burmese experts have repeatedly called for a ban on arms sales to the junta regime, but Russia has ignored such calls.[28]

Rather, Russia has been expanding its defence diplomacy activities in Southeast Asia, and not only recently but since 2010. Much of these activities are on arms sales. Its two biggest buyers in the defence domain are Vietnam and Myanmar. However, although Russia remains the biggest seller of arms to Southeast Asia, its sales are declining due to increased competition from other countries and the threat of US sanctions on governments that buy Russian weaponry.[29] Russia’s arms exports to the region accounted for 8.8 percent (US$2.7 billion) of its global sales in 2015-19, down from 12.7 percent (US$4.7 billion) in 2010-14.

Russia’s other defence diplomacy pursuits, such as combined exercises and port calls, remain infrequent and small-scale compared to those of the United States and China.

Table 1: Russia’s Defence Exports to Southeast Asian Countries, 2000-2019 (US$ million)

The lukewarm response of most ASEAN countries to the Ukraine war can be attributed to the region’s traditional wariness of meddling in other countries’ affairs, especially over what may appear to be a distant crisis in eastern Europe. Southeast Asian governments have historically followed a strict policy of non-interference in any other country’s affairs and adopting a neutral stance on issues that involve distant geographies. This principle is known as the ‘ASEAN Way’.

It is the same attitude that was seen in past issues as well as in the case of other coups taking place in Southeast Asia. “ASEAN generally prefers to avoid entering the fray,” notes Bill Hayton of the Asia Pacific Programme at the Chatham House. “It has not condemned any country for anything for at least the past 20 years.”[31]

It could be argued that Russia is not a dominant player in Southeast Asia. As analysts like Ian Storey of the ISEAS have pointed out, Russia has been a “very transactional player, and that other countries, such as Britain, have much greater interests in Southeast Asia.”[32] Yet, Russia continues to be a player in the region and has been an ASEAN Dialogue Partner since 1996. It participates in all the ASEAN-led forums, including the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF), the ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meeting Plus (ADMM-Plus), and the East Asia Summit (EAS). In 2018, ASEAN-Russia relations were elevated to a Strategic Partnership.

Russia’s current efforts at expanding its influence in Southeast Asia include adopting a five-year roadmap with the 10 ASEAN members focused on trade and investment cooperation, the digital economy, and sustainable development.[33] This framework is referred to as the Comprehensive Plan of Action (CPA) to Implement the Association of Southeast Asian Nations and the Russian Federation Strategic Partnership (2021-2025).[34] Meanwhile, at the Sixth Eastern Economic Forum held in October in Vladivostok, Vietnam expressed willingness to bridge ASEAN and Russia, and the Eurasian Economic Union.[35] Indonesian President Jokowi has repeatedly expressed his belief that “Russia might play an important role in maintaining peace and stability in the Indo-Pacific region.”[36]

While the Russia-Ukraine war is unlikely to seriously impact Moscow’s dialogue partnership with ASEAN, it could stall certain initiatives, such as Vietnam’s proposal for a free trade agreement between ASEAN and the Russia-led Eurasian Economic Union.[37] On the economic front, Singapore’s and Vietnam’s free trade agreements with the Eurasian Economic Union could provide prospects for future economic growth.

For some Southeast Asian countries, toeing the line of the United States and its Western allies is viewed with distaste. Indonesia’s foreign policy, for instance, follows the dictum of “Bebas Dan Aktif (free and active)”. Simply following the Western model and their methods is considered a breach of this free and active way of thinking.

Analysts note that Southeast Asian governments do not want to frustrate China, which has yet to offer a clearer response to the Ukraine war at the time of writing this brief. Beijing agrees that Ukraine is a sovereign state, but it also says that the European country has limited sovereignty because of choices it has made and Russia’s “legitimate security concerns.”[38] China also blames the war on Washington and Brussels and their “Cold War mentality.”[39] It has promised to maintain normal trade relations with Russia and will not support international sanctions on Moscow.

The US and other Western powers, for their part, are not happy with what they perceive as ASEAN’s “docile” response. This puts certain countries in a bind. Hanoi, for example, is looking to improve relations with Western governments, notably the United States, for both economic and security reasons. Aware that Washington and European capitals are actively attempting to form a united bloc against Russia, Hanoi may come under pressure to officially support the Western condemnation of Moscow’s invasion of a democratic state.[40]

Most countries in Southeast Asia are deciding to “hedge” in order to cooperate with both the US and China even as they also diversify relations with other countries. If Southeast Asian governments continued to acquire weapons from the US, it would frustrate Beijing. Similarly, purchasing weapons from China, as the likes of Thailand and Cambodia do, frustrates Washington. Although Vietnam has considerably improved relations with Washington in recent decades, including on the security front, it is aware that purchasing munitions from the US would ring alarm bells in Beijing. Le Hong Hiep of the ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute reckons, “Hanoi will try to diversify away from Russian arms, but that won’t be easy.”[41]

The crisis in Ukraine has once again revealed how the ASEAN is a divided house. Already beset with divisions over Chinese aggression in the South China Sea, the damming of the Mekong, the ethnic cleansing of the Rohingya, and the 2021 coup d’êtat in Myanmar, ASEAN, yet again is not taking a collective position on a security issue that has potential implications for the entire region.

A joint statement issued by the ASEAN foreign ministers on 26 February 2022[c] made no mention of Russia’s invasion of a sovereign state, let alone its targeting of civilians and effort to capture Ukraine’s main cities. The statement called on both sides to “exercise maximum restraint.” No single country was directly criticised although ASEAN did note the responsibility of all parties to “uphold the principles of mutual respect for the sovereignty, territorial integrity and equal rights of all nations.”[42]

Southeast Asia comprises small and medium-size nations that rely on international law, the doctrine of sovereign equality, and the principles set out by the United Nations that forbid the use of force to alter borders or interfere in the domestic politics of another sovereign state. Russia’s actions and justification for war have set a dangerous precedent. Yet, the ASEAN states have largely equivocated, each for its own reason.

Singapore did, however, immediately condemn Russia’s attack on Ukraine. It has since announced various sanctions, including on banking and SWIFT correspondence, the freeze on high-tech exports, and travel bans. As Singaporean Foreign Minister Vivian Balakrishnan made clear on what for his country considers to be at stake in the crisis on the other side of the globe: “We cannot accept one country attacking another without justification, arguing that its independence was the result of ‘historical errors and crazy decisions’ … Unless we as a country stand up for principles that are the very foundations for the independence and sovereignty of smaller nations, our own right to exist and prosper as a nation may similarly be called into question.”[43]

There are two ways in which the ASEAN response can be analysed. First is how ASEAN’s response impacts the regional architecture of the Indo-Pacific. Given that ASEAN and ASEAN-led mechanisms like the East Asia Summit (EAS) are being perceived as the primary forums in the region, what will be the larger outcome of this divided response from ASEAN? ASEAN centrality is a dictum which finds mention in the Indo-Pacific strategies and policies of most countries in the region, but questions are now being raised as to how the divergence of responses will affect Indo-Pacific affairs.

The ASEAN itself is also dealing with issues of territorial encroachment in disputed waters of the South China Sea, in what can be viewed as exemplifying how a big power can intrude into the sovereign space of a smaller country. This is similarly the case with Ukraine.

Not only has the divide within the ASEAN been revealed once again, but its credibility and whether it will follow the same line of action as it expects from others when it comes to disputes like those in the SCS has come under scrutiny. Knowing that Russia is a less significant player in the region compared to the US or even the EU, some countries’ soft approach towards Russia brings out the aversion in following the Western style of diplomacy. Some countries in Southeast Asia can be said to have been largely influenced by China’s position, which too, has essentially been neutral as it abstained on the draft UN Security Council resolution on 26 February instructing Moscow to stop attacking Ukraine.

China’s support for Russia has also continued in areas not directly connected to the Ukraine war. For example, China and Russia conducted on 24 May 2022 their first joint military exercise since the invasion. On the same day, a Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson said, “China-Russia relations have withstood the new test of the changing international landscape.”[44] The reason for toeing the Chinese line, may be to prevent the South China Sea issue from escalating. Indeed, recent Chinese actions in the Taiwan Strait have raised concerns in Southeast Asia. China conducted provocative military exercises adjacent to Taiwan in response to US House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s August visit, prompting the US to deploy a carrier strike group and two amphibious ships to the waters east of Taiwan. This affects the security and stability of the wider region, including the South China Sea.

Just before Pelosi’s visit, China announced that it would hold military drills in the disputed waters. As China’s belligerence has been heightening, as seen in its aggressive actions during the Taiwan crisis, Chinese leaders could deploy simultaneous and massive exercises in the contested sea to showcase Beijing’s might and win domestic support. This option could threaten the ASEAN claimant states—Vietnam, Malaysia, Brunei, and the Philippines—and widen their power asymmetry with China. ASEAN has raised its objections to China’s actions, the official stance reflecting the bloc’s desire to maintain a balancing posture amidst the simmering tensions between Washington and Beijing while seeking to uphold its status and centrality by offering to play a facilitating role. [45]

There is a general acceptance among policymakers in Southeast Asia that the notion of “ASEAN centrality” is derived not from the organisation’s strength but instead its weakness— i.e., it is not seen as threatening to anyone given that it comprises middle and rising powers. The question is whether this assumption will hold as ASEAN’s international standing rises and when there is a greater expectation from the global community for the regional bloc to do more.

Second, to ensure that ‘ASEAN centrality’ remains relevant, the bloc’s most important strategy has been to keep itself open and able to engage with all major powers. As geopolitical rivalry intensifies in the Indo-Pacific, ASEAN’s diplomacy has become even more careful while engaging the global powers.

A third assumption is that given ASEAN’s limitations, the most practical approach that suits the bloc is by persuasion and nudging over isolation and sanctions in its diplomacy engagements, which is often described as the “ASEAN Way.” This approach has been taken by ASEAN even while dealing with conflicts at home. ASEAN has not isolated its member countries even if they have been engaged in conflicts and coups, managing crises in the past by relying on diplomacy. The Cambodia-Vietnam conflict in 1978 as Vietnam launched a full-scale invasion of Cambodia[d] is a case in point. ASEAN then had refused to acknowledge the legitimacy of the Vietnam-backed leadership in Cambodia. It exerted diplomatic efforts to leave Cambodia’s United Nations seat empty until free and fair elections were conducted. ASEAN’s lobbying in the UN culminated in international support for its rejection of political subversion through military force and violation of the principle of non-interference. The crisis, which lasted from 1978 to 1991, was a mark of the organisation’s diplomatic success that was achieved through ASEAN unity.[46] In more recent years, in 2012, for the first time ASEAN failed to release a joint communique at the end of the ASEAN meeting, then foreign minister of Indonesia, Marty Natalegawa undertook ‘shuttle diplomacy’: he visited every ASEAN member country and negotiated and arrived at an understanding which finally led to the release of a statement.

Therefore, if the idea that underpins ASEAN’s notion of its centrality is less about taking strong positions on regional and global conflicts, and more about diplomatic tools, the question is whether a linear thinking of ASEAN offers any deeper understanding of the bloc. Therefore, when one talks of the stance from the Southeast Asian region on the Russia-Ukraine war, it needs to be seen from two angles. One is the position of every individual country, and the other is that of the ASEAN. If the stand of the individual countries is seen as the ASEAN response, then it will easily appear that ASEAN is divided. However, if one just looks at the ASEAN response, then it is a hedging approach that seeks to maintain cordial relations with all powers.

In the latest ASEAN Summit held in Cambodia, Russia was represented by its foreign Minister, Sergei Lavrov and Ukraine, by its Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba. Kuleba held direct talks with several leaders of ASEAN countries, where he urged them “to condemn Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, warning that staying neutral was not in their interests.”[47] The ASEAN signed the Treaty of Amity and Cooperation with Ukraine,[48] thus paving the way for the establishment of formal relations with Kyiv.

For some, the war in Ukraine is a distant issue which Southeast Asian populations can do little to influence, and any involvement would only bring unwanted difficulties. For others, the Ukraine war has very real implications for the region.

What is clear is that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is a clear violation of international law and holds lessons for Southeast Asia. ASEAN’s raison d’etre is to promote regional peace and stability through respect for justice and the rule of law. Furthermore, key principles such as respect for independence, sovereignty and territorial integrity, as well as the right of every state to maintain its existence free from external interference or coercion is enshrined in many key ASEAN documents such as the ASEAN Charter, the Treaty of Amity and Cooperation in Southeast Asia (TAC), and the ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific. Any attempt to violate these principles will cut to the core of Southeast Asian security and prosperity. Despite the perceived weakening of the ASEAN amidst its responses to issues like the South China Sea disputes and the Mynanmar coup, the role of the grouping should remain central to discussions that involve the Indo-Pacific region.

[a] These countries are having to consider boosting their relations with West Asian countries and others such as Venezuela, for example, to secure alternative supplies of oil.

[b] Russia is one of the few supporters of Myanmar’s junta regime.

[c] “The ASEAN Foreign Ministers are deeply concerned over the evolving situation and armed hostilities in Ukraine. We call on all relevant parties to exercise maximum restraint and make utmost efforts to pursue dialogues through all channels, including diplomatic means to contain the situation, to de-escalate tensions, and to seek peaceful resolution in accordance with international law, the principles of the United Nations Charter and the Treaty of Amity and Cooperation in Southeast Asia. 2. We believe that there is still room for a peaceful dialogue to prevent the situation from getting out of control. For peace, security, and harmonious co-existence to prevail, it is the responsibility of all parties to uphold the principles of mutual respect for the sovereignty, territorial integrity and equal rights of all nations.” (See)

[d] In December 1978, Vietnam invaded Cambodia. Phnom Penh fell on 7 January 1979, and a new government backed by Hanoi proclaimed the People’s Republic of Kampuchea (PRK) the next day, 8 January.

[1] Duetsche Welle, “Explained: Southeast Asia’s muted response to the Ukraine conflict”, Frontline, March 8, 2022.

[2] ASEAN Foreign Ministers’ Statement On the Situation in Ukraine, February 26, 2022.

[3] Joanne Lin, “Is ASEAN a toothless tiger in the face of Ukraine crisis?”, Asialin, March 3, 2022.

[4] Duetsche Welle, “Explained: Southeast Asia’s muted response to the Ukraine conflict” Also see, David Hutt, “What’s behind SE Asia’s muted Ukraine response?”, DW, July 3, 2022.

[5] Welle, “Explained: Southeast Asia’s muted response to the Ukraine conflict”

[6] Mirza Sadaqat Huda, “Could Russia-Ukraine conflict derail Southeast Asia’s decarbonisation efforts?”, Channelnewsasia, July 20, 2022.

[7] Manjari Chatterjee Miller, “How the Ukraine War will impact Asian Order”, Cfr, May 12, 2022, https://www.cfr.org/article/how-ukraine-war-will-impact-asian-order

[8] Ian Hill, “What the Ukraine crisis means for the Indo-Pacific”, the Interpreter, March 11, 2022.

[9] Tomotaka Shoji, “Southeast Asia and the Russian Invasion of Ukraine — Diverse Relations, Mixed Reactions”, The Sasakawa Peace Foundation, November 1, 2022.

[10] Lin, “Is ASEAN a toothless tiger in the face of Ukraine crisis?”

[11] Lin, “Is ASEAN a toothless tiger in the face of Ukraine crisis?”

[12] Lin, “Is ASEAN a toothless tiger in the face of Ukraine crisis?”

[13] Shoji, “Southeast Asia and the Russian Invasion of Ukraine — Diverse Relations, Mixed Reactions”

[14] Shoji, “Southeast Asia and the Russian Invasion of Ukraine — Diverse Relations, Mixed Reactions”

[15] Shankari Sundararaman, “ASEAN and the Ukraine Crisis: Why Centrality and Startegic Silence are not Compatible”, Kalinga International Foundation, March 28, 2022.

[16] “Russia Launches Attack On Ukraine, Indonesian Government Firmly Asks For International Law And UN Charter To Be Obeyed”, VOI, February 24, 2022.

[17] Remarks by the Spokesperson of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Viet Nam Le Thi Thu Hang regarding Viet Nam’s reaction to the escalating tensions in Ukraine and citizen protection work for Vietnamese nationals in this country, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Vietnam, June 2, 2022.

[18] “Defense chief: PH ‘neutral’ on Russia’s invasion of Ukraine”, CNN Philippines, February 25, 2022.

[19] “Myanmar’s Military Council Supports Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine”, VOA, February 25, 2022.

[20] “Myanmar’s Military Council Supports Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine”

[21] Kavi Chongkittavorn, “ASEAN responds to invasion of Ukraine”, Bangkok Post, March 1, 2022.

[22] Ian Storey and William Choong, “Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine: Southeast Asian Responses and Why the Conflict Matters to the Region”, ISEAS Commentary, March 9, 2022.

[23] Dezan Shira & Associates, “ASEAN’s Trade Relations with Russia”, ASEAN Briefing, September 6, 2022.

[24] “ASEAN-Russia Economic Relations”, ASEAN.

[25] Ian Storey and William Choong, “Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine: Southeast Asian Responses and Why the Conflict Matters to the Region;” Ian Storey, “Russia’s Defence Diplomacy in Southeast Asia: A Tenuous Lead in Arms Sales but Lagging in Other Areas”, ISEAS Perspective, March 18, 2021.

[26] Ronna Nirmala, “Indonesia Scraps Deal to Buy Russian Sukhois; Will Acquire US, French Warplanes”, Benar News, December 22, 2021.

[27] Duetsche Welle, “Explained: Southeast Asia’s muted response to the Ukraine conflict”

[28] “Myanmar’s Military Council Supports Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine”

[29] Ian Storey, “Russia’s Defence Diplomacy in Southeast Asia: A Tenuous Lead in Arms Sales but Lagging in Other Areas”, ISEAS Commentary, March 18, 2021.

[30] Storey, “Russia’s Defence Diplomacy in Southeast Asia: A Tenuous Lead in Arms Sales but Lagging in Other Areas”

[31] Bill Hayton, “ASEAN is slowly finding its voice over Ukraine”, Chatham House Expert Comment, March 4, 2022.

[32] Luke Hunt, “Russia Tries to Boost Asia Ties to Counter Indo-Pacific Alliances”, VOA News, October 15, 2021.

[33] Hunt, “Russia Tries to Boost Asia Ties to Counter Indo-Pacific Alliances”

[34] “Comprehensive Plan of Action (CPA) to Implement The Association of Southeast Asian Nations and The Russian Federation Strategic Partnership (2021-2025)”, ASEAN.

[35] Hunt, “Russia Tries to Boost Asia Ties to Counter Indo-Pacific Alliances”

[36] Lukas Singarimbun, “ASEAN members’ responses to the invasion of Ukraine: An overly cautious approach”

[37] Storey and Choong, “Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine: Southeast Asian Responses and Why the Conflict Matters to the Region”

[38] Zachary Abuza, “ASEAN Response to Ukraine Crisis a Show of ‘Diplomatic Cowardice”, Benar News, March 3, 2022.

[39] Abuza, “ASEAN Response to Ukraine Crisis a Show of ‘Diplomatic Cowardice”

[40] Nile Bowie And David Hutt, “Hanoi shy to leave Moscow for the West over Ukraine”, Asia Times, March 1, 2022.

[41] Deutshe Welle, “Explained: Why Southeast Asia continues to buy Russian weapons”

[42] Abuza, “ASEAN Response to Ukraine Crisis a Show of ‘Diplomatic Cowardice”

[43] Deutshe Welle, “Explained: Why Southeast Asia continues to buy Russian weapons”

[44] Samir Puri, “Divisions in the Indo-Pacific over Russia’s invasion of Ukraine”, IISS, June 7, 2022.

[45] Huynh Tam Sang, “The Taiwan Crisis Could Spill Over Into Southeast Asia”, The Diplomat, August 11, 2022.

[46] Eddie Lim and Daniel Chua, ASEAN 50: Regional Security Cooperation through Selected Documents (Singapore: National University of Singapore, 2017), p.49.

[47] “Biden in Cambodia as global leaders join Southeast Asian summit”, VN Express International, November 11, 2022.

[48] Dewey Sim, “Asean leaders ‘unlikely’ to chastise Russia over Ukraine war as summit season begins”, South China Sea Morning Post, November 11, 2022.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Premesha Saha was a Fellow with ORF’s Strategic Studies Programme. Her research focuses on Southeast Asia, East Asia, Oceania and the emerging dynamics of the ...

Read More +