Introduction

Thai-Japanese relations may not be regarded as having the same geopolitical import as others in the Indo-Pacific—such as perhaps those of the United States (US) and China—but they have evolved over the years and today can be described as nuanced and strategic. Some 130 years since the formalisation of diplomatic ties in 1887, Thailand counts its bilateral relationship with Japan as one of its oldest and most enduring, second only to its relationship with the US.[1] As both nations navigate the complex geopolitical currents of the Indo-Pacific, their cooperative endeavours in the economic as well as defence and security domains assume heightened significance. This brief analyses the factors driving Bangkok and Tokyo’s collaboration in the security and defence realms, and explores the extent of their cooperation in other areas like investments and energy.

Beginning in the 1950s, Japan has strategically refocused its relations with Southeast Asia, prioritising economic diplomacy to leverage these countries’ natural resources for its industries while tapping into their emerging markets. The backdrop to this shift was the Cold War, with the US seeking Southeast Asia's support for Japan's economic recovery as a bulwark against communist expansion in the region. The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) would later recognise Japan as a key dialogue partner, establishing formal relations in 1978; political ties deepened over time through regular meetings, and evolving to include security cooperation by the 1990s.[2]

Among the ASEAN and other Asian countries, Thailand has the longest history of friendship with Japan. It is currently home to the fourth largest Japanese community globally, with 80,000 Japanese nationals residing in the country, following the US, Australia, and China.[3] Bangkok serves as a hub for some 6,000 Japanese companies in manufacturing, trade, and services, making Japan the leading foreign investor in Thailand over the past four decades, contributing to 40 percent of the total foreign direct investment (FDI) during this period.[4] Both nations also actively engage in regional forums such as the ASEAN-Japan summit to address common challenges and promote regional stability.

Thailand’s Prime Minister Srettha Thavisin has taken a proactive approach to seeking foreign investments to his country, especially amid the intricate political landscape featuring a coalition government that includes a party supported by former PM Thaksin Shinawatra and pro-military factions. Srettha's outreach to Japan aligns with his domestic agenda of maintaining an expansive fiscal policy to address public discontent and strengthen his political standing.

Despite over six centuries of mutual exchanges, defence and security remained largely outside the purview of bilateral ties between Tokyo and Bangkok due to various reasons, one of which is the non-threatening nature of their historical interactions. Japan and Thailand have not been direct military adversaries, neither having territorial disputes nor harbouring other conflicts.

Rather, both have been preoccupied with their own domestic and regional security concerns: for Japan, the complex geopolitics of East Asia, particularly during the Second World War and its post-war reconstruction period; and for Thailand, Southeast Asia’s security dynamics and its own internal political developments. Moreover, Japan's post-war Constitution, imposed by the Allied forces, restricted its ability to engage in military activities beyond self-defence.[a]

In recent years, the changing regional dynamics, including China's assertiveness in the South China Sea, have provided incentives for both Japan and Thailand to expand their defence and security cooperation. Today, this includes joint military exercises, intelligence sharing, dialogues on regional security issues, and a defence cooperation agreement signed in 2022.

Economic Engagements

In 2012, Japan and Thailand elevated their relationship to a ‘strategic partnership’.[5] Ten years later, in 2022, the two countries elevated their bilateral ties to a ‘comprehensive strategic partnership’, signifying a commitment to deepening collaboration not only in traditional areas like security and diplomacy but also in fields such as trade, technology, and culture.[6]

The Japan-Thailand Economic Partnership Agreement (JTEPA), established through a bilateral free trade agreement signed in 2007, aims to position Thailand as an important destination for Japanese investors. The agreement extends a range of incentives to Japanese investors, such as reduced tariffs on goods and services, streamlined customs procedures, and safeguards for intellectual property rights. In particular, the manufacturing sector stands out as an appealing avenue for Japanese investors, given that many manufacturing businesses are not restricted and can be fully owned by Japanese entities.[7] The Industrial Estate Authority Act extends the benefit of allowing foreign investors to own land, subject to certain conditions. This regulatory framework enhances the attractiveness of Thailand as a preferred destination for Japanese investors seeking to establish a robust presence in the manufacturing domain.[8]

In this regard, Thailand is aiming to leverage its skilled workforce, strategic location, and conducive investment climate. The country boasts a well-established manufacturing industry, with specialisations in food processing, electronics, and automotives. Japanese investments will only get accentuated by Thailand's commitment to fostering a favourable environment.

Additionally, agreements such as the ASEAN-Japan Comprehensive Economic Partnership (AJCEP) and Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) have benefited both Thai and Japanese products by creating advantageous conditions. These agreements not only support the expansion of the supply chain but also facilitate access to a diverse range of high-quality raw materials.[9] Japan exports machinery, metal products, and automobile parts to Thailand; Thailand exports natural rubber, machinery, and computer parts to Japan.[10]

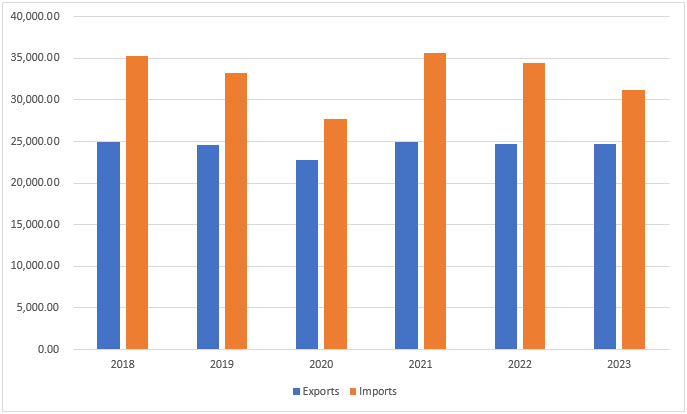

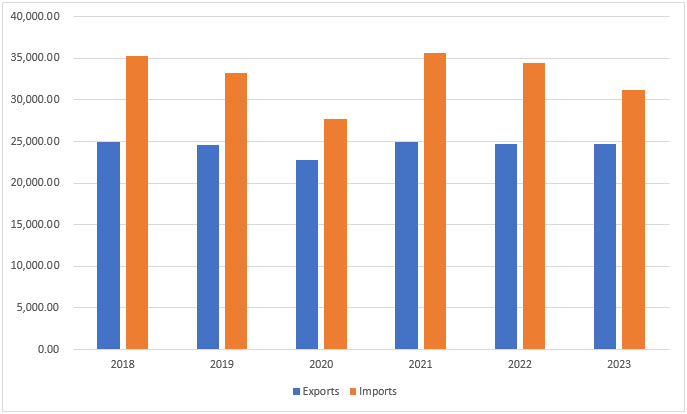

Fig. 1. Japan–Thailand Trade: Overview

Source: Authors’ own, using data from the Bank of Thailand[11]

While Japan was Thailand's second largest importer and the third largest exporter in 2019, it could not achieve all-time growth through the years due to several reasons,[12] among them the slowdown in car production in Thailand.[13] A government initiative in 2012 offering tax breaks for first-time car buyers boosted domestic car sales and increased Japanese exports and investment. However, car sales dropped when the program ended, and despite expectations of recovery in 2018 after a ban on reselling cars from the program expired, production remained below its peak due to factors like high household debt in Thailand and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on sales and exports.

Japanese investments were also impeded by rising labour costs in Thailand in the early 2010s and a change in the Board of Investment's policy in 2015 reducing tax incentives for labour-intensive industries.[14] At present, Japanese companies contribute 10 percent to Thailand's GDP.[15]

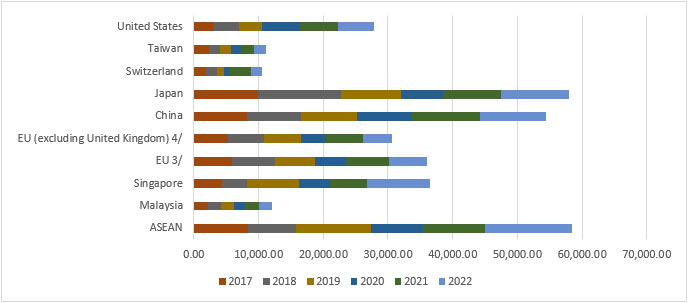

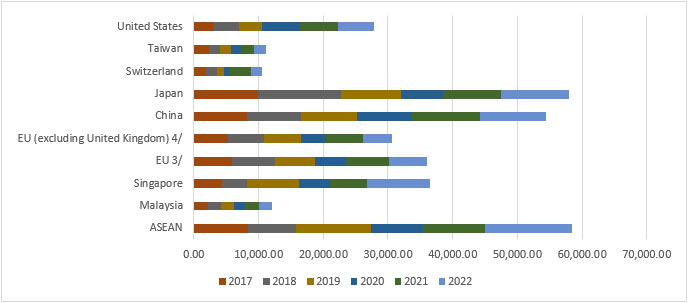

Regarding investments, according to the Business Development Department of Thailand, Japan has been the second largest investor in Thailand’s economy, next to China; it accounted for 19 percent of all the foreign investment projects in Thailand in 2023. The Keidanren, or the Japanese Business Federation, is keen on continuing to invest in Thailand, especially in businesses related to the bio-circular and green economy and automobiles.

Fig. 2. Top 10 Foreign Investors in Thailand

Source: Authors’ own, using data from the Bank of Thailand[b]

Japanese investments primarily target key industries such as automotive and automotive parts, petrochemical and chemical products, and electrical appliances and electronics.[16] Japan's significant investment in the Eastern Economic Corridor (EEC) since 2018, constituting 13 percent of total investment in Thailand, underscores a robust economic partnership.[17]

Aligned with Thailand's 20 Years National Strategic Plan (2018-2037) and the ‘Thailand 4.0 - Industry 4.0’ initiative, the nation aspires to evolve into an innovative, value-centric industrial powerhouse.[18] Its emphasis on digital, aviation, logistics, biofuels and biochemicals, and automation and robotics aligns with Japan's strengths and interests.

To foster the growth of highly skilled industrial professionals and contribute to the realisation of the vision of ‘Thailand 4.0’, the Thai government aims to introduce the Japanese KOSEN[c] education system.[19] The aim is to offer a five-year engineering education that emphasises hands-on experiments, laboratory work, project-based learning (PBL), and problem-based learning (PBL), along with a work-integrated advanced course equivalent to a bachelor's degree. Implementing the KOSEN education system can facilitate knowledge transfer to Thai students and staff in key industries, such as those in the First S-Curve[d] and New S-Curve sectors,[e] while also cultivating practical and innovative engineers capable of playing active roles in Japanese companies, particularly in invention and innovation development, including those located in the EEC.

The potential cooperation on sustainable development for economic growth by synergising Japan’s green growth strategy and Thailand’s bio-, circular, green (BCG) economic model aims to develop more resilient supply chains in industrial sectors, including through BCG activities. The EEC corridor is based on the BCG model.[20]

Japanese Official Development Assistance (ODA) has played a pivotal role in shaping Thailand's infrastructure landscape. Iconic projects like the Suvarnabhumi International Airport, key railway lines in Bangkok, as well as iconic structures like the Phra Pinklao Bridge and the Rama IX Bridge over the Chao Phraya River, stand as testaments to the impact of Japanese ODA on Thailand's development.[21] Another noteworthy endeavour, the Eastern Seaboard Development Project (ESDP), established industrial parks and ports around Bangkok, receiving ODA loans from Japan.[22] The initiative not only attracted foreign capital but also triggered an economic upswing, contributing to Thailand's growth.

Thailand is actively promoting increased investment and facilitating the transition to electric vehicle (EV) manufacturing through tax cuts and subsidies, aligning with environmental goals while attracting automotive investments.[23] Japanese automakers, recognising the growing presence of Chinese EV manufacturers, are investing in Thailand to stay competitive in the expanding EV market.

Japanese investments support Thailand's broader strategy of attracting global players in the EV industry. Chinese companies like BYD and Great Wall Motor are also committing substantial funds, totaling US$1.44 billion, for new production facilities in Thailand.[24] With proactive government measures and incentives, Thailand has become a pivotal battleground for international automakers competing for a share in the EV market.

Chinese companies, active in Thailand since 2010, are significantly impacting Japan’s stakes in the EV business. The Ministry of Finance's program promoting battery electric vehicles (BEVs) offers benefits to Chinese companies, encouraging local production by 2024-2025. Toyota is the only Japanese company involved in the BEV promotion program, reflecting a relatively slower shift to EVs compared to their Chinese counterparts.[25]

In a significant boost to Thailand's EV aspirations, Japanese automakers are gearing up to invest a total of US$4.34 billion over the next five years.[26] This investment is poised to expedite Thailand's transition to EVs, with industry giants Toyota Motor and Honda Motor committing US$1.4 billion each. Furthermore, Isuzu Motors and Mitsubishi Motors will contribute US$840 million and US$560 million, respectively, to the production of electric pickup trucks.[27]

As Thailand positions itself at the forefront of the EV revolution, the renewed actions by Japanese companies reflect not only their confidence in the local market but also a strategic recognition of Thailand's potential to play a leading role in the future of sustainable and eco-friendly transportation. This wave of investments not only supports the Thai government's environmental initiatives but also heralds a new era of collaboration and growth in the automotive sector.

Energy Cooperation

Addressing energy security has been a long-standing priority for Thailand, especially given that over half of its energy supply relies on imports. This dependence is expected to intensify further with the imminent depletion of the country's proven reserves of oil and gas, anticipated within the next decade.[28] This necessitates a shift towards alternative and indigenous energy sources to mitigate the dual risks of compromised energy supply security and escalating overall energy expenditure.

In response to these concerns, the Thai government is taking steps to address not only energy security but also environmental sustainability. A significant aspect of this commitment involves reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 20-25 percent from the business-as-usual scenario by 2030. This aligns with broader aspirations, including a goal to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050.[29]

To translate these ambitions into action, Thailand is actively implementing the 2022 National Energy Plan and the 2022 Electric Development Plan. These strategic frameworks lay the foundation for the integration of advanced technologies in the energy sector. Notably, the country is embracing technologies such as Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Storage (CCUS), EVs, Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS), grid modernisation, carbon recycling, and the use of ammonia and hydrogen.

Thailand recognises the importance of international collaboration in these domains, and a key component of its strategy is seeking technical and financial support from partners, including Japan. The country's 5-Year CCUS Roadmap (2022-2027) outlines collaborative efforts to advance carbon capture technologies.[30] In 2022, Japanese and Thai companies such as Toyota Motor and PTT demonstrated their commitment to exploring innovative solutions like hydrogen power and electric vehicles in decarbonisation technologies.[31] The discussions highlighted the importance of shared knowledge and collaborative strategies in addressing the complexities of reducing carbon emissions.

In October 2023, the initiative led by the Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand (EGAT) and three Japanese companies outlined a comprehensive approach to clean hydrogen and ammonia production.[32] The project aligns with Thailand's energy security goals and positions the country as a forward-thinking contributor to global climate action. Financial assistance from the Japan Bank for International Cooperation and Nippon Export and Investment Insurance further solidifies the commitment to turning these plans into impactful initiatives.

The 5th Japan-Thailand Energy Policy Dialogue in 2023 added another dimension to the collaboration. The discussions between Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) and the Ministry of Energy (MOE) of Thailand, along with the signing of four Memorandums of Understanding (MOUs) between Japanese and Thai companies, emphasised joint efforts towards carbon neutrality.[33] The visit of relevant Japanese policymakers to the Mae Moh power plant showcased discussions on decarbonisation strategies proposed by EGAT.

Defence and Security Relations

Tokyo has developed its ties with certain Southeast Asian nations for decades, particularly Vietnam and Indonesia. However, security ties with Thailand remained underdeveloped largely because there has been no immediate common threat for the two countries. Nevertheless, as Japan has taken on a more active role in regional security affairs, Thailand has also recognised the need for stronger defence ties to address contemporary challenges, such as maritime security, counterterrorism, and disaster relief. The two countries’ annual talks have served as a key forum for discussing security issues, enabling the two countries to synchronise their efforts in promoting stability and peace in Southeast Asia.

Initially shaped by the Second World War, the defence and security partnership has undergone transformations over the decades. In 1941, Thailand allowed Japanese forces to transit through its territory, avoiding direct confrontation and occupation. This decision was born of the necessity to preserve Thailand’s sovereignty amid the global conflict. However, it also meant that Thailand became a reluctant member of the Axis powers, which included Japan, Germany, and Italy. The post-war era witnessed a significant shift in the relationship as Japan transformed into a pacifist nation under its Constitution, while Thailand pursued a more active role in regional security affairs.

Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution renounced the right to maintain a military force for war. It marked a fundamental shift in Japan's foreign policy, making peaceful relations with neighbours and the world the country’s paramount concern. Meanwhile, Thailand's post-war trajectory was different, as it pursued a more active role in regional security affairs and became a staunch ally of the United States during the Cold War. This shift was driven by the desire to secure American support against communist insurgencies in neighbouring Southeast Asian countries and to maintain its sovereignty amid regional power dynamics.

Over the decades, Japan and Thailand have sought to reconcile their historical legacies and build a more constructive partnership based on shared strategic interests. Japan's commitment to pacifism and Thailand's regional security concerns have provided a framework for cooperation that extends to military exercises, defence technology transfers, and participation in regional security forums.

In 2017, the Thai Defence Council approved the Modernisation Plan: Vision 2026, a decade-long modernisation plan designed to enhance the readiness and capability of the armed forces to deal with potential threats.[34] The plan complements Thailand’s other master plans such as the National Strategic Development Plan (2017-2036), the National Strategic Defence Plan (2017-2036), and the Master Plan for the Defence Industry (2015-2020).[35] A key aspect of Thailand's approach to regional security is its commitment to maintaining good relations with neighbouring countries and regional organisations. It has cultivated bilateral relationships with neighbouring countries such as Myanmar, Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam, fostering cooperation on various security issues including border management, counterterrorism, and maritime security.

The Defense of Japan 2019 report[36] details Japan's strategic approaches towards security cooperation, covering the country’s efforts to actively contribute to the international security landscape, emphasising the concept of ‘Proactive Contribution to Peace’ based on the principles of international cooperation. This strategy is aligned with Japan's vision for a free and open Indo-Pacific, aiming to strengthen both bilateral and multilateral defence cooperation and exchanges, while paying attention to the unique characteristics and situations of partner nations. The report elaborates on Japan's multi-faceted and multi-layered security cooperation initiatives, including dialogues, joint training, capacity building, defence equipment and technology cooperation, and efforts in addressing global security issues in the maritime, space, and cyber domains; international peace cooperation; and non-proliferation of weapons of mass destruction.[37]

A driver for Japan seeking stronger security ties with countries across the Indo-Pacific are concerns regarding China’s increasingly assertive behaviour across the region. This has also spurred most countries in the Indo-Pacific to seek deeper security and defence-related cooperation, both bilaterally and multilaterally. This is because although China continuously asserts its clout in the region, particularly in the South China Sea, Thailand has historically maintained a neutral stance in regional disputes and has prioritised economic cooperation with Beijing. As a result, the urgency for deepening security ties with Japan may not have been as pressing for Thailand compared to other Southeast Asian nations. However, recent geopolitical shifts, such as increased tensions in the South China Sea and concerns over China, may prompt both Japan and Thailand to reassess their security cooperation and explore avenues for enhanced defence collaboration in the future.

The Role of China

Located at the centre of the Southeast Asian region, Thailand finds itself at the forefront of a shifting political landscape driven by China's rise. With its growing economy and abundant natural resources, too, Thailand has entered China’s radar for investments, cultural engagements, and immigration. At the same time, Thailand remains a strong ally of the United States, serving as an anchor for US policy in Southeast Asia and a channel for maintaining control over the Strait of Malacca.[38]

The expansion of interests between Bangkok and Beijing across political, economic, cultural, and other domains was formalised in the ‘Joint Communiqué on a Plan of Cooperation for the Twenty-First Century’ signed by Thai Foreign Minister Surin Pitsuwan and Chinese Foreign Minister Tang Jiasuan in 1999. Thailand, recognising China's rising economic influence and seeking to recover from the 1997 financial crisis, pursued cooperation with China. A strategic cooperation framework initiated in 2007, and structured through a joint action plan covering 15 areas,[f] aimed to deepen engagement and cooperation between Thailand and China.[39] The relationship between the two countries encompasses various sectors, including trade, investment, agriculture, and tourism. China's investments in Thailand have surged, reshaping the competitive landscape and positioning China as the largest investor in the country, surpassing Japan.

A critical component of sustaining China’s influence in Thailand is a continuous presence of the latter in the Thai media landscape, with China’s state-controlled media channels widely accessible throughout Thailand. Propaganda from China is regularly broadcast through television, radio, newspapers, and online platforms, catering to audiences in both Thai and Mandarin. China’s investments in Thailand's telecommunications infrastructure have bolstered Beijing's ability to influence the Thai media landscape and counterbalance pro-Western coverage.[40] The Thai social media space is also heavily influenced by China, with Chinese platforms such as TikTok and WeChat being extremely popular among the youth.[g],[41]

Other challenges for the future of Thai-Chinese relations[42] include Thailand's trade deficit with China, potential tensions over Taiwan, Tibet-related issues, and the environmental impact of Chinese dams on the Mekong River.

In contrast to neighbouring countries, Thailand has enough economic prowess and regional clout to allow itself to balance its relationship with Beijing, becoming neither overreliant nor subservient. Thailand has diversified economic ties, including with countries such as the United States, Japan, and those in the Middle East. Despite challenges posed by increased Chinese tourism and migration, Thailand maintains its independence by engaging with multiple partners and markets, ensuring a balanced approach to economic development, and has pushed back against certain Chinese initiatives, such as those related to the Belt and Road Initiative, due to concerns over costs and sovereignty. While China’s influence in Thailand has grown significantly, Bangkok manages it by employing various measures, including domestic legal parameters, security establishment checks and balances, a strong cultural value system that preserves Thai identity, and relationships with other powers. Its regulatory frameworks monitor and control media ownership, foreign business activities, and charitable organisations to regulate foreign influence. Thai security services also guard against the negative aspects of Chinese influence, such as illegal activities and misinformation, through enforcement actions and cybersecurity measures. These efforts demonstrate Thailand's ability to maintain its sovereignty amid Chinese influence.

Tokyo’s 2022 National Security Strategy outlined the Official Security Assistance (OSA) scheme, which seeks to strengthen the “security capacities” of like-minded states and improve the “deterrence capabilities” of countries in the region, particularly in the face of “China’s growing attempts to unilaterally change the status quo by force.”[43] While the OSA scheme remains modest and limits Japan’s involvement to warnings, rescue, transport, mine sweeping, and surveillance,[44] and thus far Japan has reached out only to Manila, Hanoi, and Kuala Lumpur, the scheme offers a singular framework for cooperation with other countries in Southeast Asia as well. Given the waning popularity of the BRI, with countries in the region growing increasingly cautious about debt stress and overreliance on Beijing—and the decade-long foreign policy outreach conducted by former (deceased) Prime Minister Shinzo Abe—Japan will continue to remain a key partner to these countries in terms of economic engagements, maritime security, and infrastructure. Estimates show that prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, Japan’s infrastructure commitments across the region were valued at US$367 billion while China’s were at US$255 billion.[45]

Military Cooperation

Japan and Thailand engage in joint military exercises, defence dialogues, and personnel exchanges. These military interactions serve to enhance the interoperability of their armed forces and contribute to regional stability. The exercises, for example, foster mutual understanding and cooperation, while providing opportunities for both countries to refine their operational tactics and strategies. Notable among these exercises is the ‘Pacific Partnership’,[46] a multinational humanitarian assistance and disaster relief mission where both nations participate.

Defence dialogues serve as a crucial mechanism for communication and coordination between the two nations, enabling the exchange of strategic assessments, security priorities, and policy objectives. They provide a platform for discussions on regional and global security challenges, allowing Japan and Thailand to align their perspectives and coordinate their responses. Regular consultations facilitate mutual trust and ensure that their defence policies remain attuned to emerging threats and opportunities.

Personnel exchanges between the armed forces of Japan and Thailand enhance cooperation at the operational and tactical levels. Military officers and personnel from both countries participate in exchange programs, attending training courses, seminars, and joint exercises.[47] Thailand's involvement with Japan's National Defense Academy dates back to 1958, with Thailand sending the largest number of students since. In recent years, collaboration between the Royal Thai Armed Forces and the Japanese Self-Defense Forces has contributed to international peace efforts. In 2003, Thailand deployed its engineering unit to Afghanistan for reconstruction, supported by the Japanese Maritime Self-Defense Force's transportation services. Additionally, in response to the 2003 Tsunami, Japan's Self-Defense Forces undertook disaster relief operations, including search and rescue, medical services, and delivering relief supplies. Since 2005, Japan has participated in the Cobra Gold exercise that seeks to enhance regional peace. The strong ties between the two forces are also reflected in extensive personnel exchanges.[48] Recent years have also witnessed high-level meetings between air force chiefs and capacity-building programs like seminars on aviation safety and UN peacekeeping operations. These efforts deepen mutual understanding and strengthen defence ties between the two nations.[49]

Defence Technology and Procurement

During Prime Minister Kishida’s visit to Bangkok in 2022, the two countries signed an agreement on the transfer of defence equipment and technology.[50] The deal, while similar to the ones in place with Indonesia, Vietnam, Malaysia, and the Philippines, is the first of its kind with Thailand. The agreement establishes a joint committee for determining the defence equipment and technology to be transferred for the projects “for contributing to international peace and security; joint research, development and production projects; or for enhancing security and defence cooperation.”[51] In a joint press appearance with his Thai counterpart, Kishida observed, “The signing of our defence equipment and technology transfer agreement is a major step forward in expanding bilateral defence cooperation.”[52]

Earlier efforts at procurement had met with little success. For instance, in 2016, Japan sought to negotiate the sale of Mitsubishi Electric's FPS-3 radar system to Thailand, with the Chief of Staff of Japan's Air Self Defence Force leading the discussions. However, Thailand opted to award the contract to Italian Leonardo Company, for a different radar system. Similarly, during the same period, Thailand expressed interest in acquiring Kawasaki P-1 Maritime Patrol Aircraft and ShinMaywa US-2 Air-sea rescue Amphibians when Japan's Defense Minister visited Bangkok. However, due to bilateral tensions between the US and Thailand at that time, and Bangkok having backtracked on an earlier maritime security MOU in 2013, these deals failed to materialise.[53]

The transfer of defence technology between Japan and Thailand fosters technological cooperation and strengthens the industrial base of both countries. It encourages the sharing of research and development efforts, expertise, and innovation, resulting in mutual benefits in technological advancement and self-sufficiency in defence production. The collaboration underscores the strategic alignment of their interests and the recognition of the importance of maintaining a robust defence posture in a complex security environment.

Regional Security Initiatives

Southeast Asian governments have historically regarded Japan as a pivotal trading partner and a facilitator of regional economic growth and integration. Yet, Japan's role extends beyond economics as it has become a significant diplomatic partner, advocating for ASEAN centrality and upholding Southeast Asian sovereignty in broader regional discussions. Despite the legacy of the Second World War, Japan has managed to build trust over time and is now perceived as the most reliable external power in Southeast Asia. Such trust is cultivated through Japan's approach as a considerate power that values and incorporates regional perspectives while leading quietly in areas of mutual interest. Japan recognises the crucial role of Southeast Asia and ASEAN in achieving its foreign policy and security objectives in the Indo-Pacific. This acknowledgment is demonstrated through initiatives like the ‘Vientiane Vision’,[54] enhancing defence cooperation with ASEAN. Japan also engages in bilateral agreements and consultations with individual ASEAN member states to further strengthen security cooperation across the region. Furthermore, Japan's importance to ASEAN extends to global platforms like the G7 and G20, where it amplifies Southeast Asian voices and mobilises resources to address regional concerns.[55]

Japan and Thailand are active participants in various regional security initiatives. Both countries are members of the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF), which serves as a critical platform for dialogue on political and security issues in the Asia-Pacific region. As participants in the ARF, Japan and Thailand engage in discussions on regional security challenges, such as territorial disputes, nuclear proliferation, and counterterrorism. They work with other member states to promote confidence-building measures and enhance regional security cooperation. Japan and Thailand are also integral members of the ASEAN Defence Ministers' Meeting Plus (ADMM-Plus), which brings together ASEAN member states and eight ‘plus’ countries, including Japan, for discussions on defence and security matters. Despite being part of US-led Indo-Pacific military initiatives and the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF), Bangkok has adopted a relatively reserved approach towards the strategic competition between China and the US; it has maintained a degree of ambivalence regarding its involvement in the ASEAN in the past decade.[56]

Nonetheless, it is precisely the hedging strategy that Bangkok has been known to maintain which allows the country to also engage with nations and build on bilateral convergences. Japan's commitment to a free and open Indo-Pacific (FOIP), for instance, aligns with Thailand's regional security objectives. The two nations share a vision of upholding the rules-based international order, respect for international law, and peaceful dispute resolution. Japan's FOIP strategy, with its emphasis on infrastructure development, maritime security, and connectivity, complements Thailand's efforts to promote regional stability and economic growth. Moreover, the Japan-Thailand partnership supports regional maritime security initiatives recognising the importance of maritime trade routes in the Indo-Pacific region and being engaged in promoting safe and secure seas.

Conclusion

An assessment of Japan-Thai relations reveals a relatively subdued but dynamic partnership that continues to evolve. Over the years, both countries have worked towards strengthening their ties through mutually beneficial engagements, reflecting a shared commitment to fostering regional stability and economic prosperity with a partnership that now extends across various sectors, including defence, investments, and energy.

A vital aspect of bilateral ties between the two countries is the spectre of China's influence. As China asserts its growing economic and military power in the region, both Japan and Thailand are compelled to navigate a delicate balance between maintaining their strategic autonomy and engaging with Beijing. In the realm of defence, in particular, the growth of China's military capabilities and its increasingly assertive behaviour in the South China Sea has led Japan and Thailand to deepen their security cooperation as a hedge against potential regional instability.

Although neither country seeks a direct confrontation with China, their defence collaboration contributes to the counterbalance frameworks already in place. Under President Joe Biden's administration, the US has shown renewed interest in its relationship with Thailand, enhancing military cooperation and offering assistance in modernising Thailand's defence capabilities. Fundamentally, Thailand's foreign policy underlines a commitment to maintaining equidistance between major powers while leveraging strategic engagements to safeguard its interests and autonomy.[57]

Thai foreign policy is often compared to a “bamboo swirling in the wind”,[58] alluding to its adaptability while remaining rooted in a strategic culture that blends pragmatism and adaptability to safeguard Thai interests. Thailand's tradition of balancing external interests while preserving independence is evident in its ability to sense and adjust to shifting power dynamics. Despite pressure from Washington and Beijing, Bangkok makes independent decisions to advance its interests and maintain sovereignty, avoiding alignment with either power.

Improved security cooperation between Japan and Southeast Asian nations, including Thailand, plays a crucial role in fostering regional stability and addressing common security challenges. It serves as a counterbalance to the increasing assertiveness of China in the Indo-Pacific region.

Japan's expertise and experience in security sector governance, and capacity building, can complement Thailand's efforts to modernise and enhance its security apparatus. Through sharing best practices and providing technical assistance, Japan can support Thailand in implementing reforms aimed at increasing transparency and accountability within its defence establishment. Moreover, Japan can offer support for capacity-building initiatives in both the military and civilian sectors of Thailand's security apparatus. This may include training programs, knowledge transfer, and the provision of equipment and technology to enhance Thailand's capabilities in addressing a wide range of security challenges.

Over the years, both nations have demonstrated a concerted effort to fortify their ties through a series of mutually beneficial engagements. Crucially, the partnership between Japan and Thailand has transcended traditional diplomatic channels, extending across a diverse array of sectors. In addition to defence collaboration, which has seen increased dialogue and joint exercises aimed at enhancing regional security, the two countries have expanded their cooperation to areas such as investments and energy. As they both continue to deepen their cooperation across various sectors, Thailand and Japan are poised to help shape the future of the Indo-Pacific region.

Endnotes

[a] Japan remains fundamentally pacifist. However, since the tenure of former (deceased) Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, there have been gradual yet steady revisions in policy to accommodate a greater security role for its partnerships with other countries.

[b] 3/ EU comprises 28 countries: Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, United, Kingdom, Cyprus, Czech, Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Slovakia, Slovenia, Bulgaria, Romania, and Croatia. 4/ From January 2020 onwards, EU comprises 27 countries, and the United Kingdom is excluded from the EU.

[c] "KOSEN" is derived from the Japanese term "Koto-senmongakko", which translates to College of Technology. In this context, "Koto" denotes high-level, while "Senmon" refers to engineering as a major. See: https://www.mofa.go.jp/mofaj/files/100422475.pdf)

[d] First S-Curve represents Thailand's traditional economic sectors, primarily focusing on industries such as agriculture, manufacturing, and tourism.

[e] The New S-Curve represents emerging or high-potential industries that the Thai government aims to develop further to drive future economic growth. These industries typically involve high technology, innovation, and value-added products and services. Examples of sectors in the New S-Curve may include advanced manufacturing, biotechnology, digital technology, renewable energy, and creative industries.

[f] These were political, military, trade, agriculture, industry, transportation, energy, tourism, culture, education, health, science, technology, information technology, and regional/multilateral cooperation.

[g] The extent of this influence became apparent during the COVID-19 pandemic, as China orchestrated a campaign of misinformation to mould Thai public sentiment propagating conspiracy theories and false information, including on the virus's transmission.

[1]Koki Shigenoi (Ed.), “Japan’s Role for Southeast Asia Amidst the Great Power Competition”, Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, April 2022, https://www.kas.de/documents/267709/18041095/Japan%27s+role+in+South+East+Asia+amidst+the+great+power+competition+%28English%29.pdf/160eef85-d166-9d09-3388-f6a30afdbe10?version=1.0&t=1651143907700

[2] Tomotaka Shoji, “Pursuing a Multi-dimensional Relationship: Rising China and Japan’s Southeast Asia Policy”, in Jun Tsunekawa (Ed.) The Rise of China: responses from Southeast Asia and Japan, National Institute for Defense Studies, (2009), https://www.nids.mod.go.jp/english/publication/joint_research/series4/pdf/4-6.pdf

[3] Japan-Thailand Relations (Basic Data), Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, March 3, 2023, https://www.mofa.go.jp/region/asia-paci/thailand/data.html#:~:text=Number%20of%20Japanese%20Nationals%20residing,2022)

[4] “Thailand and Japan: Celebrating 135 years”, The Japan Times, September 26, 2022, https://www.japantimes.co.jp/country-report/2022/09/26/thailand-report-2022/thailand-japan-celebrating-135-years/

[5] Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Kingdom of Thailand, https://www.mfa.go.th/en/content/joint-japan-2?cate=5d5bcb4e15e39c306000683e

[6] Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Kingdom of Thailand, https://www.mfa.go.th/en/content/joint-japan-2?cate=5d5bcb4e15e39c306000683e

[7] ILCT, “Investing in Thailand: A Legal Overview for Japanese Outbound Investors”, ILCT advocate and solicitors, https://www.ilct.co.th/japanese-outbound-investors-2/

[8] ILCT, “Investing in Thailand”

[9] The Thailand-Japan Economic Forum, The Thai Chamber of Commerce and Board of Trade of Thailand, (2023), https://www.thaichamber.org/public/upload/file/news/0706231688610845file.pdf

[10] Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, Government of Japan, https://www.mofa.go.jp/region/asia-paci/thailand/data.html#:~:text=Number%20of%20Japanese%20Nationals%20residing,2022)

[11] Bank of Thailand, https://www.bot.or.th/en/home.html

[12] Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, Government of Japan, https://www.mofa.go.jp/region/asia-paci/thailand/data.html#:~:text=Number%20of%20Japanese%20Nationals%20residing,2022)

[13] Shotaro Kumagai, “Economic Challenges for Thailand’s New Government”, RIM Pacific Business and Industries XXIII, No. 89, (2023), https://www.jri.co.jp/en/MediaLibrary/file/english/periodical/rim/2023/89.pdf.

[14] Shotaro Kumagai, “Economic Challenges for Thailand’s New Government”

[15] “Thailand: Japan’s top investment destination and key partner for social and economic development in the ASEAN region”, Bridges, Connecting countries. Bridging business. September 7, 2021, https://sms-bridges.com/thailand-japans-top-investment-destination-and-key-partner-for-social-and-economic-development-in-the-asean-region/

[16] The Thailand-Japan Economic Forum, The Thai Chamber of Commerce and Board of Trade of Thailand, June 2023, https://www.thaichamber.org/public/upload/file/news/0706231688610845file.pdf

[17] “The Thailand-Japan Economic Forum”

[18] “The Thailand-Japan Economic Forum”

[19] Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Government of Japan, https://www.mofa.go.jp/mofaj/files/100422475.pdf

[20] “The Thailand-Japan Economic Forum”

[21] Japan International Cooperation Agency, “Project for Revitalization of the Deteriorated Environment in the Land Reform Areas through Integrated Agricultural Development (Stage I)”, JICA, https://www.jica.go.jp/Resource/thailand/english/activities/loan02.html

[22] “Project for Revitalization of the Deteriorated Environment in the Land Reform Areas through Integrated Agricultural Development (Stage I)”, l

[23] Shashwat Sankranti, “Japanese automakers inject $4.3 billion into Thailand's EV transition”, WION, December 26, 2023, https://www.wionews.com/business-economy/japanese-automakers-inject-43-billion-into-thailands-ev-transition-673578

[24] Sankranti, “Japanese automakers inject $4.3 billion into Thailand's EV transition”

[25] Shotaro Kumagai, “Economic Challenges for Thailand’s New Government”

[26] Sankranti, “Japanese automakers inject $4.3 billion into Thailand's EV transition”, 8

[27] Sankranti, “Japanese automakers inject $4.3 billion into Thailand's EV transition”, 8

[28] APEC, APEC Oil and Gas Security Exercise in Thailand 5th APEC Oil and Gas Security Exercise Bangkok, Thailand, 6-7 September 2023 APEC Energy Working Group February 2024, https://aperc.or.jp/file/2024/2/21/OGSE_in_Thailand_2024.pdf

[29] Thailand’s Long-term Low Green House Gas Emission Development Strategy, November 2022, https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/Thailand%20LT-LEDS%20%28Revised%20Version%29_08Nov2022.pdf

[30] Thailand’s Long-term Low Green House Gas Emission Development Strategy

[31] Yohei Muramatsu, “Toyota, PTT and others discuss advancing Thailand's carbon efforts”, Asia Nikkei, October 21, 2022, https://asia.nikkei.com/Spotlight/Environment/Climate-Change/Toyota-PTT-and-others-discuss-advancing-Thailand-s-carbon-efforts

[32] Pooja Chandak, “EGAT Joins Forces With Japanese Giants To Advance Clean Hydrogen And Ammonia Production”, Solar Quarter, October 11, 2023, https://solarquarter.com/2023/10/11/egat-joins-forces-with-japanese-giants-to-advance-clean-hydrogen-and-ammonia-production/

[33]“The 5th Japan-Thailand Energy Policy Dialogue Held”, METI, January 17, 2023, https://www.meti.go.jp/english/press/2023/0117_002.html

[34] Asian Military Review, “10 Year Modernisation Plan for Thai Military gets Green Light!”, Asian Military Review, October 23, 2017, https://www.asianmilitaryreview.com/2017/10/10-year-modernisation-plan-for-thai-military-gets-green-light/

[35] Asian Military Review, “10 Year Modernisation Plan for Thai Military gets Green Light!”

[36] “Security Cooperation” in “Strategic Promotion of Multi-Faceted and Multi-Layered Defence Cooperation”, (2019), https://www.mod.go.jp/en/publ/w_paper/wp2019/pdf/DOJ2019_3-3-1.pdf

[37] “Security Cooperation”

[38] Ryan D. Skaggs, Nitus Chukaew, and Jordan Stephens, “Characterizing Chinese Influence in Thailand”, Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs, (January-February 2024), https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/JIPA/Display/Article/3606690/characterizing-chinese-influence-in-thailand/#_ftnref3

[39] Chulacheeb Chinwanno, “Rising China and Thailand’s Policy of Strategic Engagement”, in Jun Tsunekawa (Ed.) The Rise of China: responses from Southeast Asia and Japan, National Institute for Defense Studies, (2009), https://www.nids.mod.go.jp/english/publication/joint_research/series4/pdf/4-3.pdf

[40] Ryan D. Skaggs, Nitus Chukaew, and Jordan Stephens, “Characterizing Chinese Influence in Thailand”

[41] Jane Tang, “China’s Information Warfare and Media Influence Spawn Confusion in Thailand”, Radio Free Asia, May 13, 2021, https://www.rfa.org/english/news/china/thailand-infowars-05132021072939.html

[42] Chulacheeb Chinwanno, “Rising China and Thailand’s Policy of Strategic Engagement”

[43] Cabinet Secretariat, Government of Japan, https://www.cas.go.jp/jp/siryou/221216anzenhoshou/nss-e.pdf

[44] William Choong, “Japan’s Arms Transfers to Southeast Asia: Upping the Ante?”, Fulcrum, Feb 15, 2024, https://fulcrum.sg/japans-arms-transfers-to-southeast-asia-upping-the-ante/

[45] Michelle Jamrisko, “China No Match for Japan in Southeast Asia Infrastructure Race”, Bloomberg, June 23, 2019, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-06-23/china-no-match-for-japan-in-southeast-asia-infrastructure-race

[46] “On a Mission to Help in the Indo-Pacific”, U.S. Department of Defense, October 20, 2023, https://www.defense.gov/News/Feature-Stories/Story/Article/3561876/on-a-mission-to-help-in-the-indo-pacific/

[47] “Security Cooperation”

[48] H.E. Mr. Kyoji Komachi Ambassador of Japan to the Kingdom of Thailand, “Thai-Japanese Relations: Its Future Beyond Six Hundred Years” ( speech, September 7, 2010), http://www.asia.tu.ac.th/journal/EA_Journal53_1/Art1.pdf

[49] “Security Cooperation”

[50] “Japan, Thailand ink agreement on defense transfer amid China's rise”, Kyodo news, May 2, 2022, https://english.kyodonews.net/news/2022/05/da80b790fa6a-japan-thai-pms-meet-over-ukraine-crisis-defense-cooperation.html

[51] Agreement Between the Government of Japan and the Government of Kingdom of Thailand Concerning the Transfer of Defence Equipment and Technology, (2022), https://www.mofa.go.jp/files/100346185.pdf

[52] “Japan, Thailand ink agreement on defense transfer amid China's rise”

[53] Victor Teo, “Japan’s Weapons Transfers to Southeast Asia: Opportunities and Challenges”, Yusof Ishak Institute, no. 70, (2021), https://www.iseas.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/ISEAS_Perspective_2021_70.pdf

[54] Japanese-Thai Defense Relations in the Indo-Pacific Era, German Institute for Japanese Studies, February 20, 2023, https://www.dijtokyo.org/event/japanese-thai-defense-relations-in-the-indo-pacific-era/

[55] John D. Ciorciari, “Japan as a diplomatic asset to ASEAN”, East Asia Forum, October 5, 2023, https://eastasiaforum.org/2023/10/05/japan-as-a-diplomatic-asset-to-asean/#:~:text=Japan%20has%20also%20emerged%20as,external%20power%20in%20Southeast%20Asia

[56] Jittipat Poonkham, “Thailand’s Indo-Pacific Adrift? A Reluctant Realignment with the United States and China”, Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs, (January-February 2024), https://media.defense.gov/2023/Dec/05/2003352247/-1/-1/1/JIPA%20-%20POONKHAM.PDF

[57] Christopher S. Chivvis, Scot Marciel, Beatrix Geaghan‑Breiner, “Thailand in the Emerging World Order”, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, October 26, 2023, https://carnegieendowment.org/2023/10/26/thailand-in-emerging-world-order-pub-90818

[58] Arne Kislenko, “Bending with the Wind: The Continuity and Flexibility of Thai Foreign Policy”, International Journal, (2022), https://www.jstor.org/stable/40203691

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PDF Download

PDF Download

PREV

PREV