India’s progress on public healthcare has failed to keep up with its economic growth over the past decades, putting a binding constraint on the economy, Niti Aayog’s 2018 report, ‘Healthy States, Progressive India’, said.

Ranking states and union territories (UTs) on a Health Index, the report noted that compared with India’s economic progress and achievements, its rates of improvement in health outcomes have remained lower than those recorded in developing countries with comparable levels of spending on health. This, along with the middle-income trap that a member of the Prime Minister's Economic Advisory Council recently warned about, are fundamental risks for the Indian economy. While the governance deficit in the health sector is mainly a result of low public investment, the problem is compounded by the lack of regular, quality data that can inform decision-making and facilitate course correction at the sub-state levels.

While the governance deficit in the health sector is mainly a result of low public investment, the problem is compounded by the lack of regular, quality data that can inform decision-making and facilitate course correction at the sub-state levels.

The government’s Health Management Information System (HMIS), often the only source for sub-district level health data, is riddled with problems. In 2013, a government committee reportedly found that the actual number of malaria deaths in the country would be at least 20-30 times higher than earlier estimates. In 2015, the number of estimated deaths by tuberculosis (TB) in India needed to be doubled(480,000) compared to the estimated number in 2014 (220,000).

Today, more than ever, better measurement, greater evidence and more informed reporting are expanding voter awareness and deepening policy debates. This makes it imperative for central and state governments to improve the quality of public health data, we argue in the third report of our ongoing series on data, healthcare and public policy.

The National Family Health Survey-4 (2015-16), an independently conducted survey, showed India’s immunisation coverage at 62%; many well-off states’ performance had actually worsened. For a comparable time period (2014-15), HMIS showed the percentage of fully immunised children to be consistently above 100%, as Observer Research Foundation pointed out.

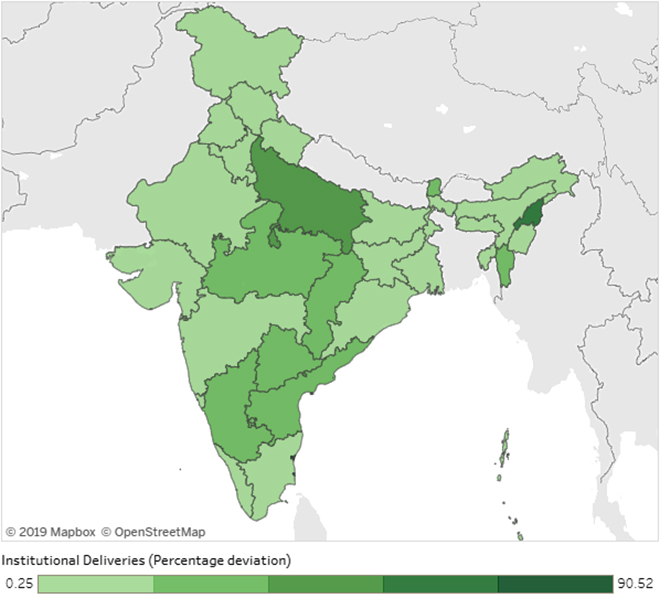

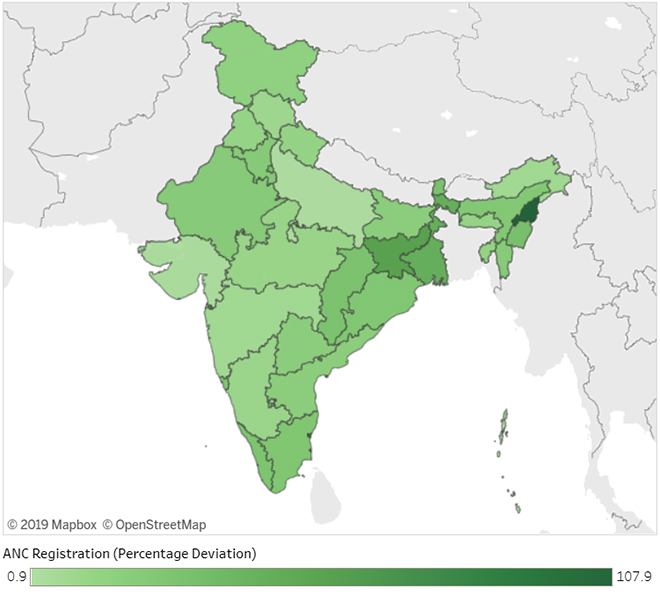

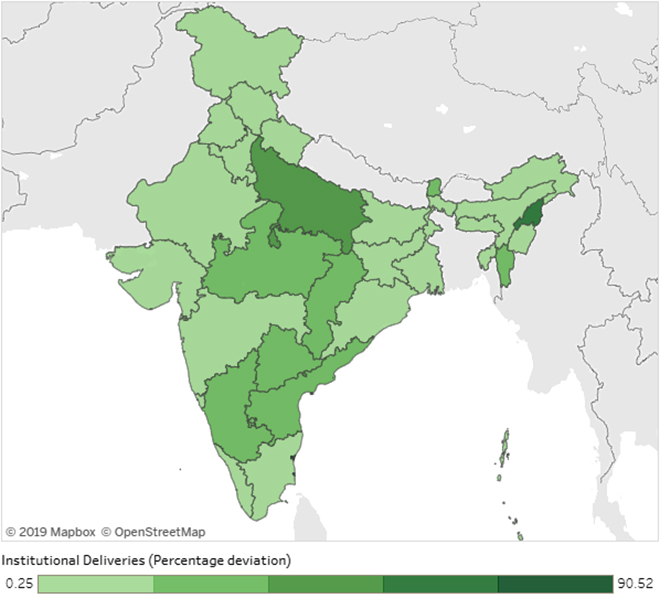

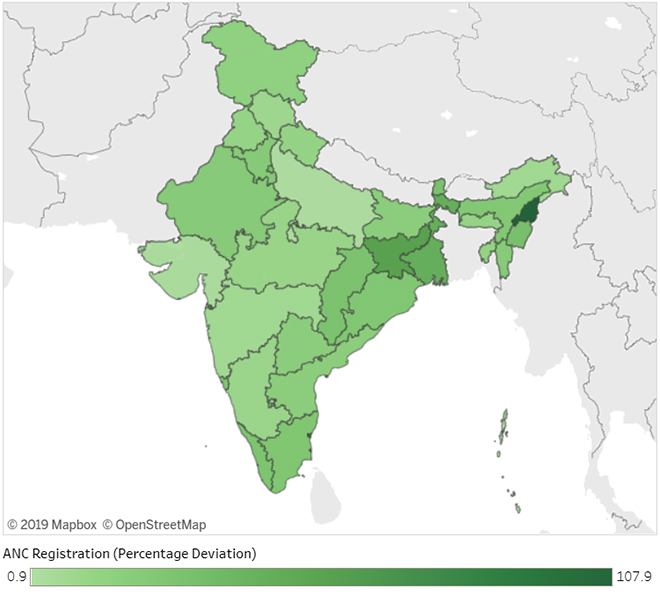

The Niti Health Index explored this issue of governance deficit including the quality of official data collected at the state level by capturing the percentage deviation of HMIS data from the NFHS-4 data in order to assess its quality and integrity. Specifically, five-year data from HMIS (2011-12 to 2015-16) on the proportion of institutional deliveries (births in health facilities as opposed to people’s homes) and ante-natal/pregnancy checkups (ANC) registered within the first trimester were compared with NFHS-4 conducted during 2015-16. These indicators were chosen as they are sensitive to the responsiveness of the health system to maternal and child health conditions.

Map 1 shows the wide variation across Indian states and union territories (UTs) in terms of discrepancy between HMIS and NFHS-4 data on institutional deliveries.

Of the top 10 best performing states in terms of the quality of HMIS data, eight are currently ruled by the Bharatiya Janata Party and allies (BJP+), the Niti Health Index comparison showed.

Uttar Pradesh (BJP+), Nagaland (BJP+) and Puducherry (ruled by the Indian National Congress and allies, or INC+) have the widest discrepancy between HMIS and NFHS-4 data and are hence the worst performers.

Of the bottom 10 states and UTs that have an assembly, four were ruled by INC+ and three each by the BJP or regional parties or alliances.

Map 1 Data Integrity: Institutional Deliveries (Percentage Deviation)

Source: Healthy States, Progressive India, 2018

Source: Healthy States, Progressive India, 2018

The case of ANCs registered within the first trimester represented in Map 2 had Nagaland (BJP+), Jharkhand (BJP+) and Puducherry (INC+) presenting the widest variation between HMIS and NFHS-4 data.

Uttar Pradesh (BJP+), which was among the states ranked among the bottom three performers in terms of quality of data on institutional deliveries, was ranked at the top on reliability of ANC registration data.

However, the bottom three performers in terms of quality of data on ANC registration included two from institutional deliveries rankings, namely Nagaland (BJP+) and Puducherry (INC+). Here, too, states and UTs with assemblies currently ruled by BJP+ dominated the top 10 best performers in terms of reliability of HMIS data, numbering seven. Gujarat (BJP+) and Maharashtra (BJP+) were part of the top three on both rankings.

Map 2 Data Integrity: First Trimester ANC Registration (Percentage Deviation)

Source: Healthy States, Progressive India, 2018

Source: Healthy States, Progressive India, 2018

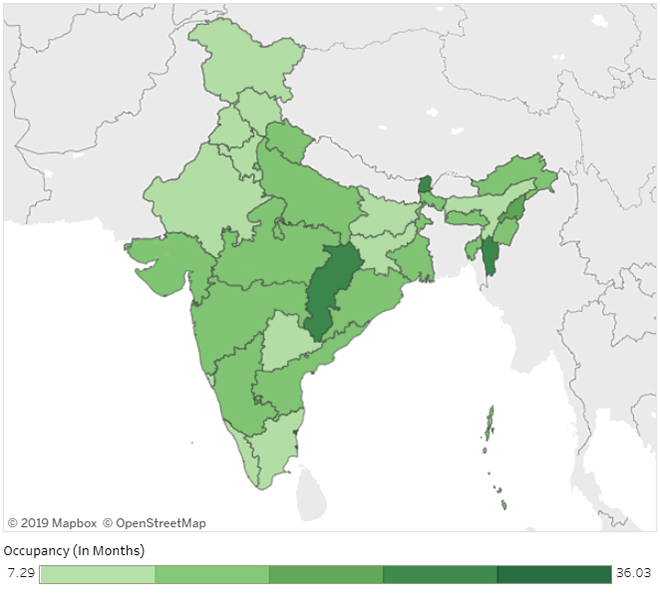

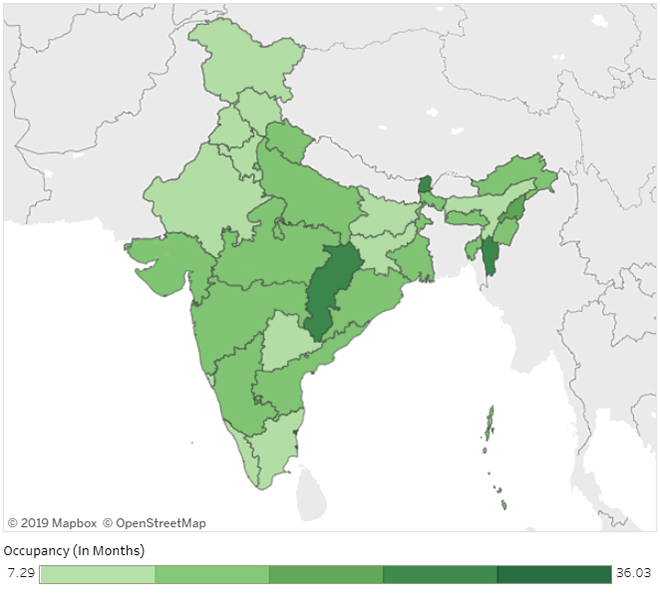

As Map 3 shows, the Niti Health Index data on average occupancy of district-level government health leadership find that in one-third of the states and UTs, the average occupancy of a full-time Chief Medical Officer (CMO) or equivalent post heading the health services of the district is 12 months or less, thus hindering the effective implementation of programmes. Only a small number of states and UTs with assemblies -- Mizoram (Mizo National Front and allies, or MNF+), Sikkim (BJP+), Chhattisgarh (INC+) and Puducherry (INC+) reported an average occupancy of more than 24 months.

Map 3: Average occupancy: Chief Medical Officers (in months)

Source: Healthy States, Progressive India, 2018

Source: Healthy States, Progressive India, 2018

With a long-term perspective of health system development, the Centre and states have to make sure that health sector leadership at the district level spends a sufficiently long time at one duty station to catalyse change.

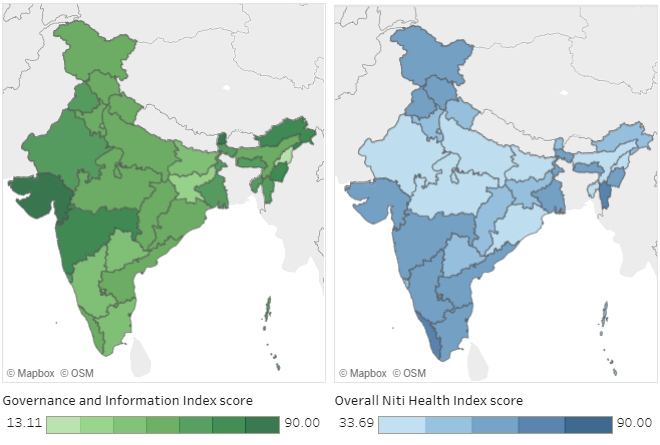

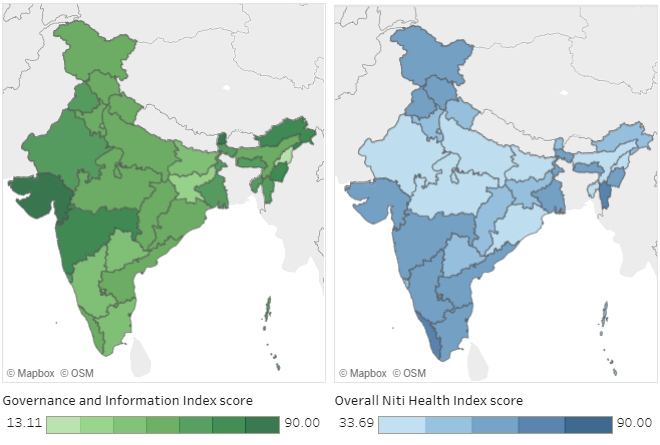

The Niti Health Index also provided sub-domain rankings because overall performance does not reveal specific areas requiring further attention. In fact, states and UTs’ governance and information sub-domain scores and rankings differ considerably from their scores and rankings on the overall health index.

Particularly for the South Indian states that do well on the overall health index, domain-specific performance on ‘governance’ and ‘information’ is not as impressive.

Map 4: Overall Health Index Score Vs Governance and Information Domain Index Score

Source: Healthy States, Progressive India, 2018

Source: Healthy States, Progressive India, 2018

As Map 4 demonstrates, all South Indian states, including Kerala (CPIM+) that is ranked highest on the overall performance index, do relatively badly on the governance and information criteria. This calls into question the quality of the health management structures in the states including the quality of data collected by their health management information systems.

There is an urgent need to improve the data system in health for timeliness, accuracy and relevance. The Niti Health Index makes it clear that the overall performance of the system does not guarantee a high quality of information and governance practices. Among the bigger states, Gujarat (BJP+) and Maharashtra (BJP+) remain exceptions in this.

This commentary originally appeared in Health Check.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Source: Healthy States, Progressive India, 2018

Source: Healthy States, Progressive India, 2018 Source: Healthy States, Progressive India, 2018

Source: Healthy States, Progressive India, 2018 Source: Healthy States, Progressive India, 2018

Source: Healthy States, Progressive India, 2018 Source: Healthy States, Progressive India, 2018

Source: Healthy States, Progressive India, 2018 PREV

PREV