Introduction

The International Labour Organization (ILO) defines ‘social security’ broadly as “protection that a society provides to individuals and households to ensure access to health care and to guarantee income security, particularly in cases of old age, unemployment, sickness, invalidity, work injury, maternity or loss of a breadwinner.”[1] The term ‘social security’ therefore covers a variety of benefits, ranging from insurance and pensions to disability and unemployment benefits. These instruments aim to provide a basic level of income and access to health facilities for all, and to develop safety nets in situations of crisis. In 2016, the World Bank and the International Labour Organization jointly adopted the Universal Social Protection (USP) 2030 Call to Action that commits countries, international partners and institutions to ramp up efforts towards meeting the global commitment on “social protection for all” declared in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) 2030 Agenda.[2]

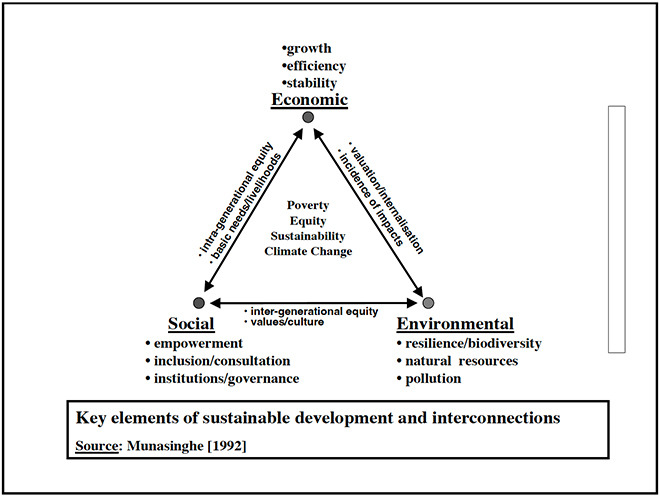

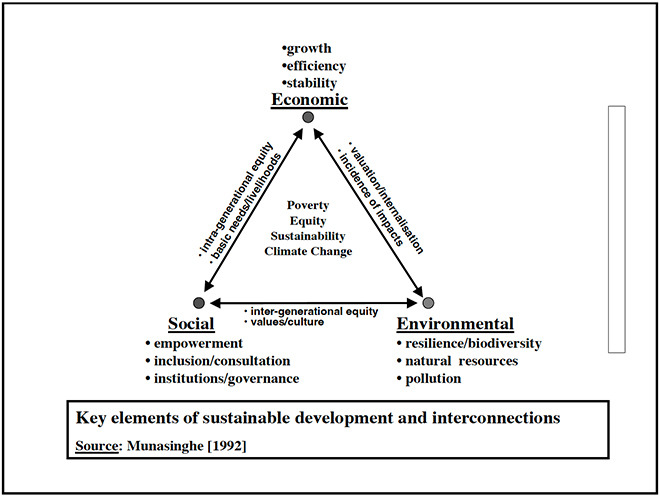

While social protection has historically been identified as a responsibility of the State, countries have made concerted efforts to diversify their systems to accommodate various forms of social security financing. These mechanisms seek to leverage different forms of capital assets—human, physical, social, and natural[a]—that they have at their disposal. The “sustainomics” framework recognises the critical role of social security in the achievement of the sustainable development goals.[3] This meta-framework enables the sustainability aspect of development through a transdisciplinary integrative approach, balancing the economic, societal and environmental aspects of development (see Figure 1). Social security features in all the three pillars of sustainomics. While social security accelerates inclusive growth for economic progress, on one hand, it also hinges on the societal tenets of empowerment and peace and strong institutions, thus leading to human capital development. Again, the role of ecosystem services in providing livelihood opportunities to the vulnerable socioeconomic classes is undeniably a crucial component of social security; this will be discussed in the latter sections of this paper.

Figure 1: Key Elements of ‘Sustainomics’

Source: Sustainomics Framework, Mohan Munasinghe [4]

A diverse set of instruments are used to operationalise comprehensive social protection frameworks across the world. These need to be designed in consideration of the needs and vulnerability of various sections of society and in relation to their contextual realities. Economic and social vulnerability can vary across variables such as gender, social groupings, socio-economic status, age, extent of labour force participation, and nature of employment. While assuming different approaches, social protection everywhere aims to primarily advance the first Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) of ‘No Poverty’ (see Appendix 1). Target 1.3 of SDG 1 focuses on the provision of nationally appropriate social protection floors with coverage to all persons. Adequate provision of social security has been shown to contribute significantly to poverty alleviation as well as economic growth, along with advancements of other related SDGs.

At present, however, only 47 percent of the world’s population are covered by some form of social security programmes.[5] The remaining 53 percent are left without any safety net in case of crises, whether at an individual, local, or global scale. The COVID-19 pandemic, for instance, was one such crisis that underlined the need for adequate provision of social security. In the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic and its economic fallout, significant populations were left without their regular sources of income nor any alternative, and they did not have social protection floors to cushion the shocks.

Across countries, the pandemic has had the worst impacts on those with the lowest income levels, and the least social security. The bottom 40 percent of the global population lost 6.7 percent of their average incomes, as compared to only 2.8 percent for the top 40 percent.[6] This loss in income additionally emphasises the repercussions of such an event for those without adequate social protection. Indeed, the social protection gap between the developing economies and the advanced nations has also expanded because of the COVID-19 pandemic.[7]

This is true for the Group of Twenty (G20) that brings together some of the largest advanced and emerging economies around the world.[8] While noticeable improvement in social protection coverage was necessary to sustain the demand-supply dynamics of product and factor markets across the G20 economies through the pandemic, this also led to increasing gaps in social security financing. For the emerging G20 economies, pre-existing challenges to universal social protection—namely, economic informality, narrow tax base, illicit financial flows, profit shifting and fiscal space considerations—were exacerbated by the pandemic.

The present study, while underscoring the need for adequate provision of social protection, focuses on their effective coverage across the G20 economies. After all, the G20 is home to 63 percent of the global population, and therefore, can collectively provide universal social protection for the majority. The following sections investigate the existing divergences and gaps in social security financing among the advanced and emerging economies of the G20 and suggests approaches to ensure financial sustainability of social protection systems around the world. Through its presidency of the G20 over the next year, India can play a pivotal role in guiding the agenda of the G20 Development Working Group (DWG) around social security issues, especially in the domain of poverty mitigation. Focusing on the priorities of the USP2030, the G20 can work together to develop innovative models that cater to financial sustainability and progressive universality of social protection frameworks, especially for the emerging, developing and underdeveloped economies of the world.

Social Protection in the G20 Economies

Collectively, the G20 countries can work to ensure social security for about 63 percent of the global population.[9] Indeed, over the years, the G20 countries have made significant progress towards improving access to social security, and consequently, in poverty alleviation and reducing inequality. Expanded social security has likely also had implications for other domains of development, including improvements in energy access, technology uptake, productivity enhancements of various forms of capital, and overall social progress. However, none of these countries are on-track to achieve the SDGs within the ongoing ‘Decade of Action’.[10] As most SDG targets are intrinsically linked with poverty alleviation and economic growth, there is an unequivocal need to improve the provision of social security to achieve progress towards Agenda 2030. The G20 Leaders’ Declaration in Rome emphasised the importance of adequate social protection with a human-centric approach that considers the needs of the working people and the labour market for driving post-pandemic economic recovery.[11]

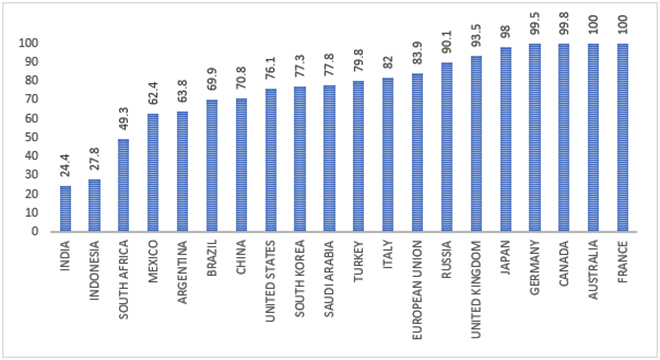

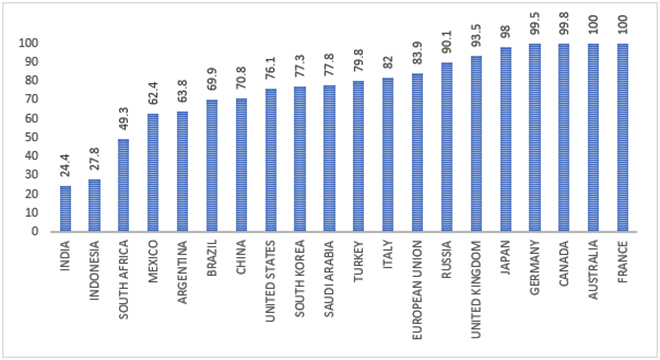

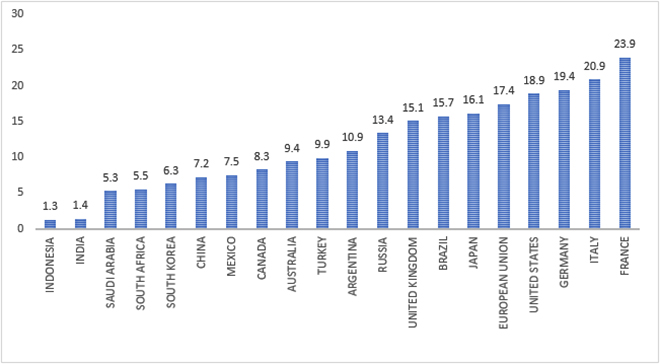

To be sure, the coverage of social security across different regions of the world vary. Upper middle-income countries show 90-percent coverage, while lower middle-income countries, less than 30 percent. The proportion falls to 15 percent for low-income countries.[12] In the advanced economies of the G20, more than 75 percent of the population are covered under at least one social protection benefit; this average is a lower 60 percent in the emerging G20 economies. Among the latter, India and Indonesia have significantly low social protection coverage of the bottom 40 percent of their populations (see Figure 2). This indicates a positive correlation between income levels and social protection coverage—i.e., countries with higher income levels are likely to have higher social protection coverage, and relatively low financial sustainability considerations.

Therefore, economic growth is an important determinant of social security coverage, and social security schemes should be designed in a manner that ensures there will be no negative effects on income growth. Moreover, properly designed social protection may also exert a positive effect on future incomes and therefore can reduce any financial stress within the social protection systems. This forms the basis for provision of graduation support programmes, as part of social protection frameworks.[13]

Figure 2: Effective Social Protection Coverage in the G20 economies (% of population)

Source: Authors’ own, using data from World Social Protection Data Dashboard [14]

Note: Effective social protection coverage is defined as the proportion of the total population receiving at least one contributory or non‑contributory cash benefit, or actively contributing to at least one social security scheme.

A G20 report on ‘Strengthening Social Protection’ (2018) recognises the role of social security in transforming labour markets as well as in facilitating labour mobility through portability of social security benefits.[15] It also identifies the challenges that countries around the world confront in providing social security, particularly to those engaged in non-standard forms of employment. The need for social protection provisions and the challenges associated with it have only been exacerbated (and highlighted as such) by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Gaps in Social Security Financing

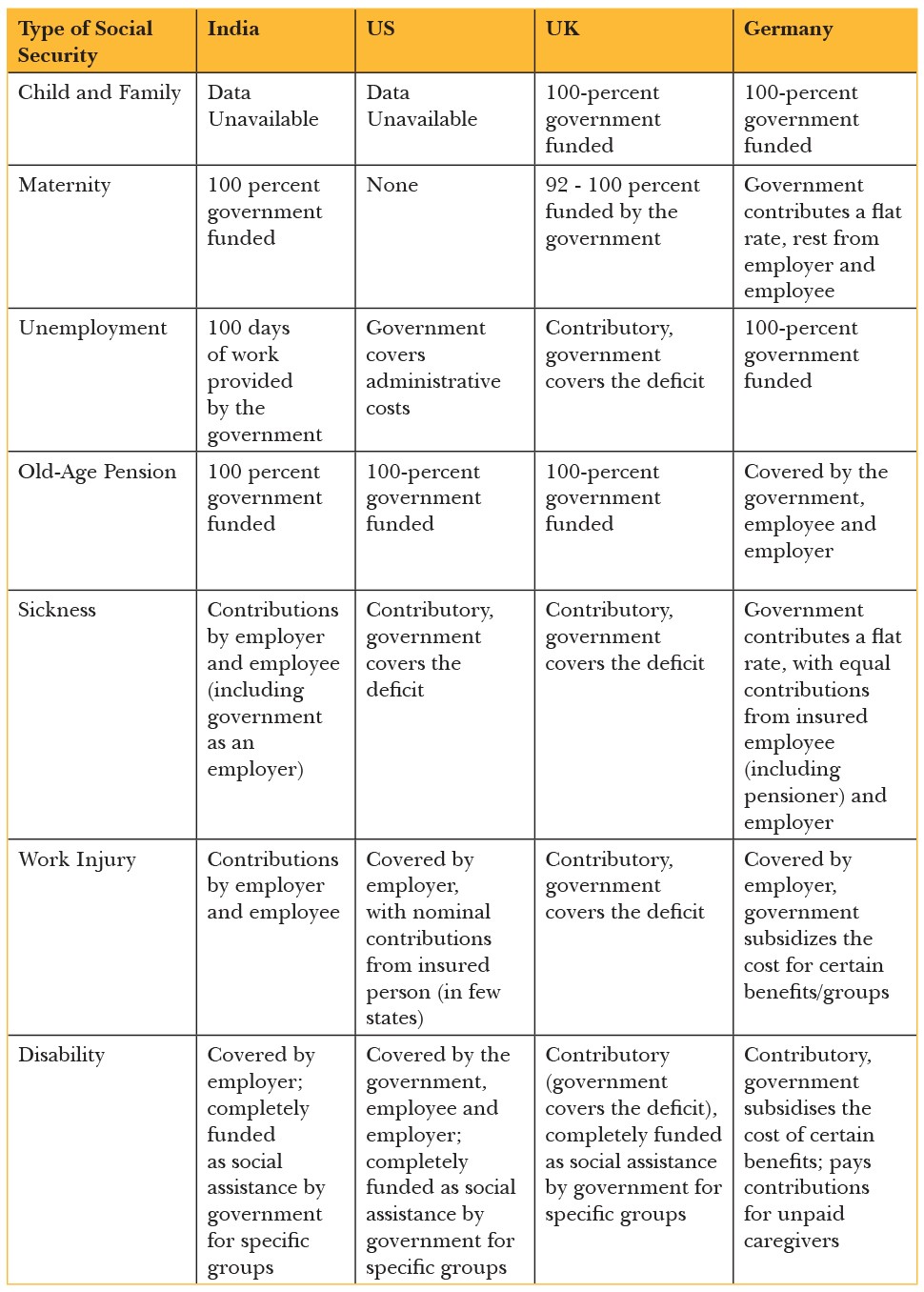

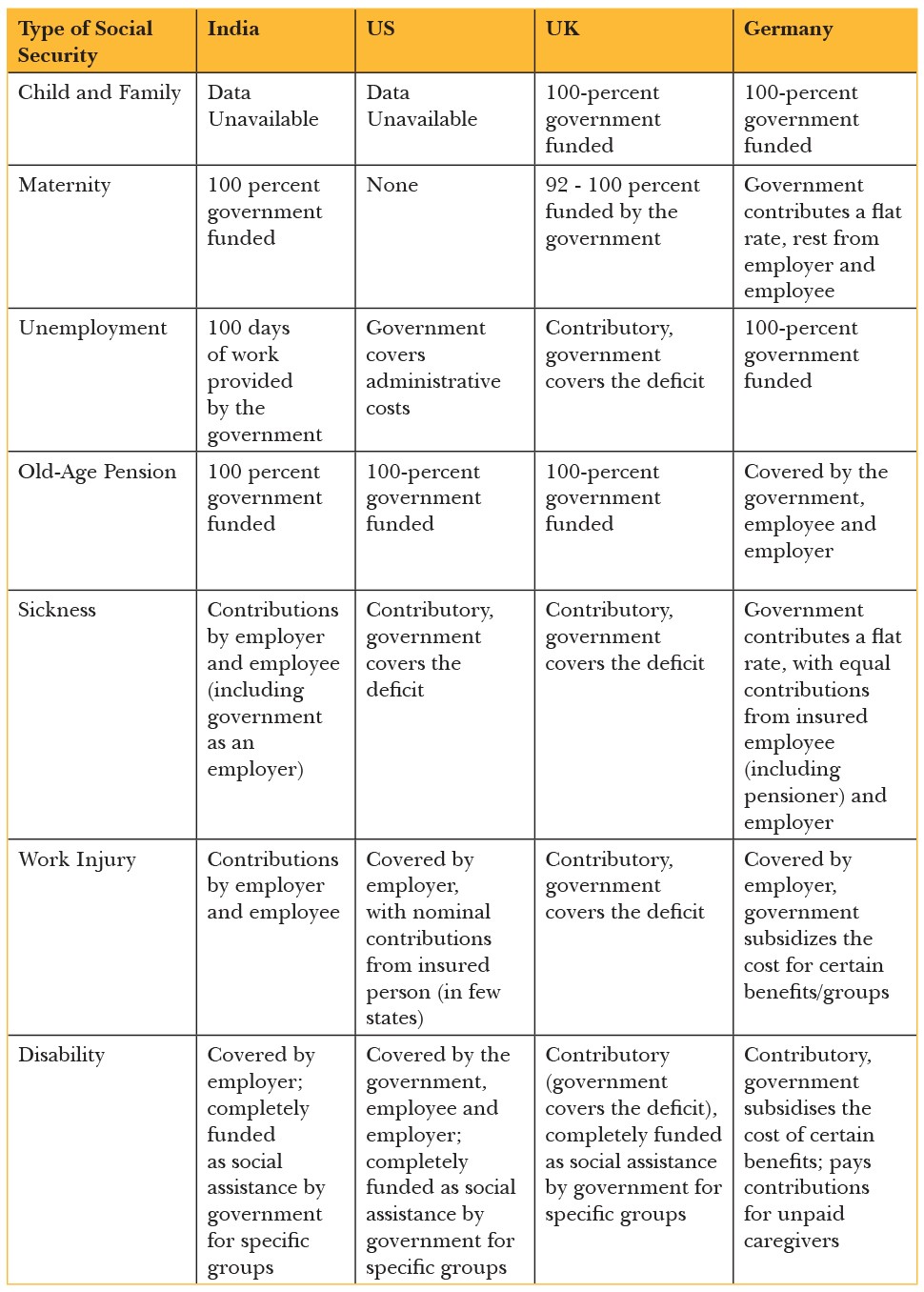

The provision of social security measures continues to be absent in significant populations across the world. Among the G20 states, there are large variations in the financing of these social security programmes. Other than the EU, most developed counties have lower state involvement in the financing of social security, with these being mainly contributory schemes[b] and the responsibility being borne by the employer and the employee themselves. [16] In contrast, developing countries continue to have a larger share of State-sponsored schemes. Brazil has significant involvement in social security provisioning for its workers,[17] although this has reduced since austerity measures were introduced in 2016.[18] South Africa, meanwhile, adopts a mixed approach—with some schemes such as the Skill Development Levy (SDL) being sponsored by employees,[19] while others, which are targeted directly at the vulnerable sections of the population, are sponsored by the state.[20] India, too, has a mix of both forms of social security: some benefits like maternity benefits are publicly funded, and others like provident funds involve contributions from both employers and employees. Table 1 shows the nature of funding for different social security instruments, for specific target groups, across select G20 economies.

Table 1: Nature of Social Security Programmes (India, US, UK, Germany)

Source: Authors’ own, using data from International Labour Organization[21]

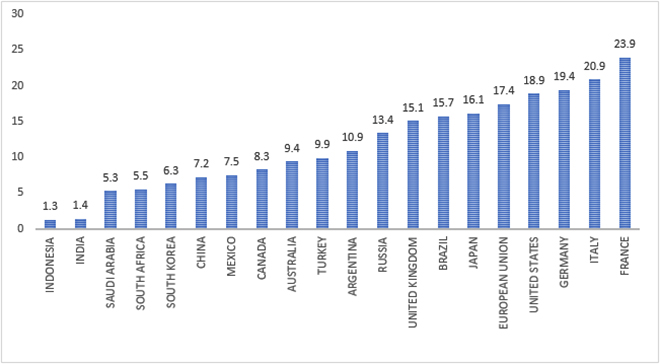

However, despite lower state involvement in ensuring social protection in the global North, the advanced economies of the G20 spend a significantly larger share of their public spending on social expenditure (see Figure 3). Combined with significant private sector participation, this indicates that the financing of social assistance in these advanced economies is conducive to a robust social security system with widespread coverage. On the other hand, the emerging economy members of the G20 spend a considerably lower share of their GDP in public provisioning of social protection. Besides, social assistance expenditure in these countries is often treated as residual expenditure amidst inadequate financing, leaving the most vulnerable sections of the population in these countries to their own devices in times of crises. For example, in most South Asian economies, low public spending on health leads to high out-of-pocket expenses, often placing the poorer and vulnerable households under severe debt burden.[22]

The USP 2030 Agenda aims to ensure social protection coverage of the entire population by at least one form of contributory or non-contributory social security instrument. The preceding discussion, therefore, has been limited to total social expenditure. However, a disaggregated analysis should reveal more interesting relationships that can motivate further work in this domain, in terms of guiding target group specification and budgetary redistributions within the broader ambit of the universal social protection agenda.

Figure 3: Social Protection Expenditure in the G20 Economies (% of GDP)

Source: Authors’ own, using data from World Social Protection Data Dashboard [23]

Note: Public social protection expenditure includes expenditure on services and transfers provided to individual persons and households, and expenditure on services provided on a collective basis by the government.

It is important, in this aspect, to stress that while state provision of social security needs to be increased, there are associated financial implications. In Brazil, for example, about 12-13 percent of the country’s GDP goes into paying only pensions. Meanwhile, for larger developing economies like India, the tax-revenue-to-GDP ratio is a low 16 percent, which necessitates diversification of social security instruments to expand the coverage for its population. Therefore, public provisioning of social protection (i.e., increasing social expenditure as share of GDP) should be examined keeping in mind the fiscal sustainability indicators such as tax-revenue-to-GDP ratio.

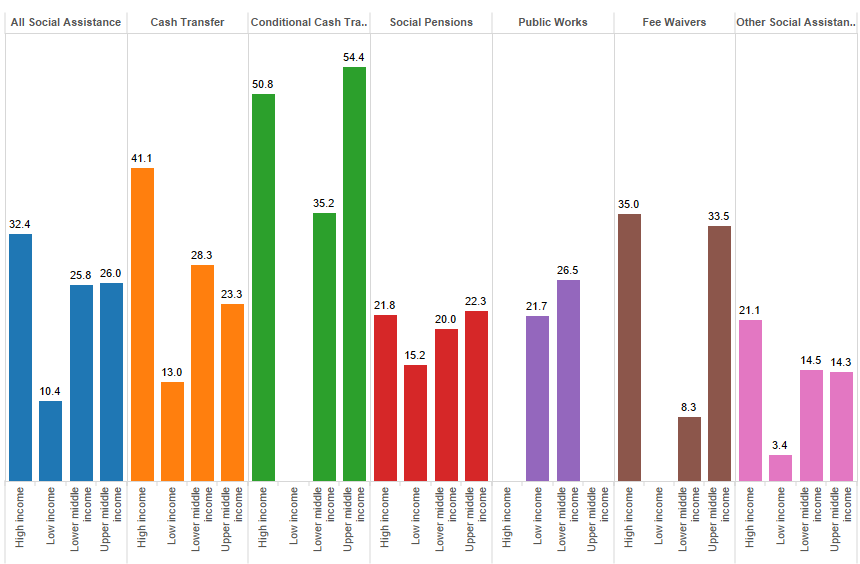

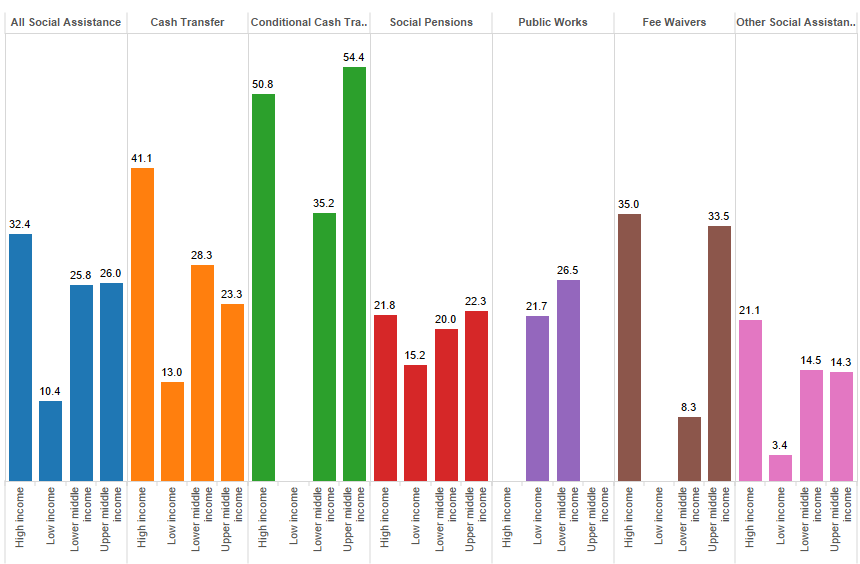

The same is true for other countries, and not only the G20. There are large categorical variations in the proportion of budgetary allocations made to social security provisions. In high-income countries, this proportion is 16.4 percent of the public spending on average, as compared to 8 percent in upper middle-income countries, a far lower 2.5 percent in lower middle-income countries, and a meagre 1.1 percent in low-income countries. Moreover, the nature and incidence of social protection benefits is also marked by significant divergences among countries belonging to different income groups.

Figure 4 shows the nature and extent of coverage of various kinds of social protection schemes among the poorest quintile of population across countries, qualified by their per capita income levels. The overall coverage, including all kinds of social protection benefits, is significantly higher for the high-income economies and mostly include conditional and unconditional direct-beneficiary transfers. The same is true for high middle-income countries. On the other hand, social assistance in the low and lower middle-income countries mostly involve public works programmes that cover roughly 21-27 percent of the population in these countries. This indicates the relevance of sustainable financing of social security for these countries to ensure greater coverage and diversification of social assistance benefits.

Figure 4: Nature of Social Assistance Coverage of the Poorest Quintile (in %)

Source: The World Bank [24]

The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the lives and livelihoods of the poor in many parts of the world. As a response, many countries introduced temporary measures of social security, ranging from insurance to income substitution measures. However, most countries also faced disruption to their tax collections and other revenues over the same period. For developing or underdeveloped nations with significantly restricted tax bases[c] and a larger share of population in need of social protection, this meant expanding expenses, contracting funds and therefore, larger fiscal deficits. For developing countries, the direct taxation base is significantly small—which makes the total tax base of the country narrower.[25] This also indicates that while a large number of people in these countries need social protection for livelihood security, very few can actually participate in financing contributory schemes from their own incomes. Therefore, public social protection expenditure in these countries is often constrained by fiscal deficit targeting, which is critical to ensuring their macroeconomic stability in the medium-run.

A 2019 study by the International Labour Organization (ILO) found that to close the financing gap in provision of basic social security across countries, an additional cumulative investment of US$ 735.2 billion or about 1.25 percent of GDP of low- and middle-income countries would be required by 2030.[26] Of this, the low-income countries would need incremental financing worth 3.78 percent of their GDP, compared to 1.34 percent and 1.16 percent of their GDP for lower middle-income and upper middle-income countries, respectively. The report suggests improving tax revenues collection, reducing illicit fund transfers, reallocating public money, and managing debt as suitable methods to ensure increased funding of social protection. Divergences in the provisions of social security have implications for the socio-economic development of the global population as a whole.[27] Considering this, the G20, as a strategic multilateral forum of the world’s largest advanced and emerging economies, must make some systemic changes to ensure that the overall sustainability of social security financing is improved in these countries and other developing and underdeveloped nations.

A Sustainable Financing Approach towards Social Protection

Financial sustainability of social protection systems is a prerequisite to ensuring robust social security for all. While countries strive to establish such systems that can improve the economic resilience of the most vulnerable and guarantee an equitable protection for the remaining population guided by progressive universalism, they need to explicitly account for the financing considerations of these systems. Financial sustainability is one of the most crucial operational constraints that threaten the economic sustainability of social protection systems. Therefore, social protection systems should be designed with the aim to balance state-sponsored and privately-funded schemes—catering to inclusive needs and prioritisation of target groups; effective last-mile delivery; and, most efficient realisation of benefits by the beneficiaries. The ILO Convention No. 102 makes specific recommendations to ensure sustainable financing of social security for countries around the world, which include the following:[28]

- Financing of social security should be under the general responsibility of the State and treated as critical public provisioning;

- Social security financing cannot be residual expenditure and must be viewed as a counter-cyclical tool to protect the most vulnerable against cyclical fluctuations and market failures, to aid shock absorption, and ensure overall economic and social resilience for all;

- Social security financing should also be responsive to the general economic trends that adjust for variations in subsistence needs and the adequacy needed to meet them.

Despite these broad recommendations, divergences in social security financing persist. In lower-income countries, a small share of the population is covered by social security; the coverage is primarily concentrated in the formal sector and closely related to income and political economy considerations.[29] In contrast, middle- and high-income countries have social security arrangements that cover most of the population and exhibit a larger expenditure share in the GDP. Structural adjustments to accommodate financing considerations within the design of social security systems and instruments can enable the G20 countries to ensure sustainability of its social protection in the long term. Systemic improvements can simultaneously increase the reach of social security, mitigate disparities in social protection in the global North and the global South, and contribute towards poverty alleviation and economic growth for all.

Streamlining Social Protection Systems in G20 Countries

There are large divergences between the provision of social security in the global North and the global South. The same is true for the G20 member countries. There are also significant differences in social security needs within these countries, with different kinds and sizes of vulnerable populations. Such divergences should not just feature in individual countries’ considerations and interests, as they hold implications for the global population.[30] There are also large financing gaps, and the capacity to mitigate these is varied.

Associated challenges can be addressed, to some degree, if countries come together to create a broad framework under which the provision of social security at the individual country level is nested. There exists a range of social security instruments—qualified by their mode of benefit transfer or beneficiary, system’s design and/or financing—that countries resort to. They include universal benefits—applying to all without any additional qualification criteria—and those that are targeted at specific demographic groups eligible for a social security programme. Offering a range of benefits—in the form of Direct Beneficiary Transfers (DBTs), employment guarantee and public works, graduation and income-generating programmes, and/or, natural capital assets or community-based programmes that particularly focus on ecotourism and payment for ecosystem services (PES)—these instruments can be either contributory, non-contributory, or voluntarily financed.

Despite large variations in the components of individual social security systems, streamlining the broader social protection framework across the G20 can be a critical step forward. This could involve setting up standardised levels of social security and creating evidence-based policies and guidelines about which aspects should be prioritised. While the details and the level of coverage depends on local context and needs,[31] having such a process in place could make it easier to design social security instruments.

The first step towards such streamlining would be to set up a system that monitors specific aspects of the social security system in various countries. This could begin by measuring the types and sizes of vulnerable populations that exist in the specific country, and to what extent they are covered by social security measures. The same should be tracked and monitored at regular intervals. This would not only help track progress along SDG target 1.3 but could also be used to draw linkages around the implications of social security on the economy and the lives of the beneficiaries. There is a need to deliberate on how such a system will be operationalised and what major targets it should be monitoring. Additionally, there is a need to design and develop processes and indicators to measure the success, if at all, of these systems. At present, indicators (as included in the SDGs) talk about the broad goal of social security coverage, but having comparable systems in place could enable the evaluation of more specific operational aspects.

The framework can also be used to design collaborative practices amongst different stakeholders. This would include various stakeholders within a country—i.e., employer groups, labour groups, the state—but could operate at an international level. There could be collaborations amongst the governments of different countries, and could additionally benefit from participation of international organisations as well, to facilitate sharing of finances, technology, and know-how as and when required. This would be particularly important considering the changing nature of work.

The framework should be made comprehensive by including predictable vulnerabilities within its design. These include not just economic vulnerabilities but also environmental. With the growing impacts of climate change, and the disproportionate consequences on developing countries, there is likely to be a greater strain on finances and resources for providing social security.[32] This would manifest in multiple ways, primarily losses in livelihoods because of change in climate patterns and increased frequency and intensity of disasters. If these are appropriately included in the framework right from the start, it would make it more sustainable in the long run.

The G20 DWG should also explore methods for how such a framework can be sustainably financed. Such financing cannot depend on grants or similar assistance since these are likely to be one-off. Rather, it must depend on sources that the member countries are able to generate themselves. The framework could institutionalise collaboration amongst member countries to address this.

Financing Social Security for Unorganised Workers

Many common forms of social security, such as pensions and insurance, are employment-linked. However, this excludes from its purview, those outside the formal employment sector or else are engaged in what the ILO refers to as ‘non-standard’ and ‘vulnerable’ employment.[33] About 60 percent of the world's workforce is engaged in work outside the formal sector,[34] with limited or no access to social security. This bears significant implications for their economic resilience and social mobility.[35] The size of the informal sector in developing countries is particularly large, leaving a large number of people outside of the formal security net, forced to fend for themselves in the face of crises.

There are unique challenges associated with expanding social assistance programmes to include the informal sector.[36] It is difficult to design systems of compulsory contributory social security for these workers and sustain them. With the evolution of new forms of employment, such as gig work and the platform economy, it often becomes difficult to even define who the employee is, let alone to design specific systems targeted for them.[37]

Developing and financing social security for unorganised workers requires unique attention. While designing a response to the social security financing gap, schemes specifically targeting this sector need a two-pronged approach: to create adequate fiscal space to finance assistance in the short run, and to capitalise on existing assets and capacities to generate opportunities for self-financing of social security in the long run. To address immediate concerns, the G20 DWG must develop frameworks for thorough evaluations, including a cost-benefit analysis, of extension of social protection to the informal sector. This should also include the challenges and associated administrative costs, such as those of maintaining registries and enforcing compliance. Consequently, social security must be designed in a manner that minimises the cost of compliance and administration.

G20 member countries may already be providing different forms of social security to informal workers, in response to the specific needs of their target population. For example, India has undertaken targeted financial inclusion programmes to promote self-employment and social entrepreneurship among women and other minorities—to advance their social security agenda.[38] These attempts have often been aided with graduation support[d] and assistance by private players like non-government organisations (NGOs) and Self-Help Groups (SHGs), all in turn, leading to increased formalisation of the large informal sector.[39] Specific cases can be studied to identify best practices. While it may not be possible to replicate these best practices in other jurisdictions owing to the differences in the target groups, as well as in the local context, they could serve as a broad guide for the countries that are struggling to make any considerable progress. There is also a need to focus on both social insurance and social assistance measures[40] with relatively low adoption and implementation costs—efficient mechanisms of providing social security can help alleviate the financing gap to some extent.

An additional challenge, in this case, would be the sheer number of people who will now be included in these schemes. Since a large section of the population in developing countries is in the informal work sector,[41] covering them would put a strain on the finances of the state. This is particularly important, as the challenges to contributory schemes make it more likely that they are non-contributory in nature. A systematic approach to financing must be adopted to mitigate this challenge.[42] It is essential to keep in mind the unique nature of employment of these workers, and not merely attempt to expand the coverage of traditional DBT schemes of social security to aid these workers—directly impacting the financial sustainability of all State-sponsored social security.

For initial expansion of these projects, some countries may need to depend on external financing from development organisations and international financial institutions. In the long run, it is necessary to ensure that the process is self-sustaining financially. Social security measures are themselves likely to contribute significantly to the alleviation of poverty and to economic growth in general, and consequently to improving the financial strength of the country. Therefore, once expansion is carried out, the dependence on social security measures is also expected to decline, except in situations of crisis. This is a long-term process, and many countries may not have the resources to enter them immediately, thus underscoring the role to be played by external financing.

Developing Robust Social Security Delivery Systems

An important aspect of social security systems, as with any other policy that is aimed to directly reach people, is last-mile delivery. Having in place comprehensive policies and systems of social security would contribute little if the last-mile delivery is inadequate. Robust delivery systems ensuring last-mile delivery in an efficient manner reduces overall transaction costs, lending considerably to the prospects of financial sustainability. The efficiency or strength of a social security delivery system can be tracked through the actual realisation of benefits by the target beneficiaries.

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted this imperative, as it posed unique challenges to the system of last-mile delivery. Some countries had in place adequate systems and were able to tide through their challenges.[43] In many cases, these were tech-enabled, and therefore were barely affected by restrictions on mobility. On the other hand, many of the temporary systems for COVID-19 relief were set up without thorough planning. Many of these faced challenges in identifying and locating beneficiaries, at the very least, more so in ensuring that the benefits are transferred to them. While the government could respond at the time of the crisis to introduce the necessary measures, it was hardly the appropriate time for it to introduce many new systems.

There is a need to have in place robust systems of social security delivery. While technology can play a large role in improving last-mile delivery of social protection provisions, it is necessary to keep in mind the digital divide while designing these systems. At a more general level, it is necessary to ensure that these systems fit the needs of the target population, and that they have the means and resources to access them.

The first step that the G20 countries need to focus on in terms of improving last-mile delivery would be to identify the challenges. These are likely to be unique, based on the location and the target population group that the measures are aimed at. The challenges could be formidable—identification of beneficiaries, enforcement of social security, and ensuring access, as well as navigating social and cultural practices that tend to limit service delivery.

For instance, there may be challenges related to identifying who is a participant in a particular industry. This may be exacerbated in the current environment of increasing gig and platform work. There may be challenges in enforcing social security practices in small industries because of the sheer number of entities that would have to be monitored at any given time. If technology-based solutions are used to improve access to social security, then the two aspects of having access to technology and digital literacy will have to be considered. It must also ensure that social security reaches the intended beneficiaries. For example, maternity benefits must be designed in a way that they reach the intended beneficiaries even in situations where cultural practices do not usually allow women control of financial resources.

Ensuring that benefits of the provision of social security are effectively utilised, can go a long way in promoting enthusiasm among participants in improving these systems. Therefore, studies on the benefits of the same and awareness activities can help bring these into the focus of the policymakers. This research and advocacy must focus on the necessity of social security, as well as the challenges faced in accessing the same. There is also the need to understand the broader macroeconomic implications of social security to help justify the financing of these projects.

The most efficient forms of social assistance would need to make use of digital technology in the changing world order. Therefore, it would be wise of institutions, especially in the developing countries, to focus on improving the reach of this technology. Improving access to digital infrastructure, as well as taking adequate steps to improve digital literacy would mean that the governments are able to deploy efficient tech-based systems at all steps of providing access to social security. This process would also have implications that go far beyond the appropriate provision of social security.

Like other processes, last-mile delivery too, can benefit from collaboration between stakeholders. Collaboration between international players in the G20 grouping can help ensure that best practices from other countries are adapted and used to ensure the quickest upgrades to the social security process. There is also scope in making use of the expertise of the private sector. Engaging in public-private partnerships could enable better adoption and utilisation of technology and other related processes while still ensuring that the direction of the private sector remains cognisant of social needs.

Role of Ecosystem Services

In addition to developing a formal state-led social security framework, there is also potential in developing a social security framework that is more organic and community-led. The same will alleviate the burden on the state system and lower the requirement for financing. At the same time, it can produce the same benefits that a formal social security system provides, serving as a safety net against crises. Looking at the potential of ecosystem services in the provision of social security requires allowing the people to have control over the benefits that are derived from these natural resources.

The G20 working group, as a first step, could link environmental programmes to social protection programmes in the relevant countries.[44] Social protection programmes tend to be designed with little regard, if at all, for the environmental aspects. Environmental programmes, while considering certain aspects of social impacts, do not give them primacy. Linking these would mean designing social security programmes in a way that the environment and natural resources around communities are not exploited further, where often this exploitation occurs in the absence of any other resources or financial safeguards.

At the same time, the G20 must draw the reverse link of how environmental damage is likely to affect and increase the social security burden. This becomes a crucial part of deliberations within the ambit of South-South cooperation under the G20, focusing on the sustainable use of the natural capital endowments in the poorer nations. As specified earlier, environmental vulnerabilities must be considered while designing frameworks for the provision of social security. Looking at these two ideas in consonance, can have a reinforcing effect on each other, and improve the condition of both.

Previous research has established how ecosystem services constitute the “GDP of the poor.”[45] While environmental exploitation should be discouraged, people should be enabled to make sustainable use of their natural resources. With appropriate training on how to sustainably yet lucratively make use of these natural resources, people will be able to generate a stream of income that can act as a self-provided form of social security. For instance, the ecosystem services provided by the Sundarbans in Bangladesh contribute significantly to the well-being of the people in the area,[46] and if managed well could reduce the requirement for social security.

Furthermore, many ecotourism opportunities, which are also prevalent in the Sundarbans, provide dependable channels of livelihoods for the financially vulnerable sections of the population. This is essentially an alternative to state-sponsored social security and will help reduce the burden on the state for financing the same. Many developing countries with abundant resources have the opportunity to make use of this method of providing social security. However, global and local interests in terms of conservation, development and tourism are often at loggerheads with each other. Uddhammar’s (2006) study on four protected areas in India and Africa found that governance structures, local ownership of resources, and institutions for solving such disputes have been most successful.[47]

To make this social security successful, however, the ownership of these natural resources and the profits they bear must remain with the people or the community. Even within the community, there should be parts that are controlled by the poorest and most vulnerable members[48] to ensure that they receive benefits as well. These resources cannot be used in an exploitative manner by the private sector or even by the government. In a way, this form of social security that is reliant on the ecosystem services provided by the natural environment is a return to more traditional forms of social security[49] that some of these communities have historically depended on.

The Case of India’s MGNREGA

Poverty remains among India’s most intractable developmental concerns since Independence. The legacies of the centuries-long colonial rule, compounded by the massive geographical size of the country and the diversity of its population, have posed unique impediments to poverty eradication. Although dealing with poverty has been a difficult task for the successive political dispensations, the various social security schemes for poverty mitigation have been instrumental in bringing down poverty rates, especially in the past decade. While there are various studies analysing poverty in India, the latest analysis by World Bank in April 2022 estimates the poverty head-count rate at 10.2 percent in 2019, down from 22.5 percent in 2011.[50] An April 2022 IMF study pegs the extreme poverty levels at lower than 1 percent in 2019, and similarly in the pandemic inception year of 2020.[51]

To eradicate poverty in the country, the Indian government has initiated multiple programmes to provide social protection, sustain poverty escapes, and generate employment. The NITI Aayog[52] cites the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act 2005 (MGNREGA), the National Rural Livelihood Missions (NRLM) and the Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana (PMJDY) as seminal programmes in the domain of mitigating rural poverty and progressing towards SDG 1 with an aim to “end poverty in all its forms everywhere” (see Appendix 2).

The world’s largest social welfare programme—the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act—[53] is a 2005 legislation that makes mandatory 100 days of guaranteed employment to be provided in a financial year to every rural household in the country. It can be considered as the culmination of several employment assurance schemes from the 1960s to the early 2000s. One of the core objectives of the programme is to strengthen the livelihood resource base of the poor or wherever it fails to do so, to provide them compensation. This Act provides employment in the form of unskilled labour for at least one adult individual in a family and one-third of the employment has been reserved for women. To ensure public accountability, the Act lays down provisions for a social audit function and the management of data and records of employment.[54]

As the first objective in both the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) in 2000 and the SDGs in 2015, poverty eradication is given utmost importance for emerging and developing countries such as India, since it is the first step towards ensuring just and equitable growth. A number of other social security programs for poverty alleviation in India include: the National Social Assistance Scheme that provides pensions to the elderly, widowers as well as individuals with disabilities; the Pradhan Mantri Jeevan Jyoti Bima Yojana (PMJJBY) and the Pradhan Mantri Suraksha Bima Yojana (PMSBY) that facilitate the access to life insurance and personal accident insurance to citizens; the Atal Pension Yojana (APY) for pension guarantee to the unorganised sector; the Pradhan Mantri Mudra Yojana (PMMY) that provides loans to aspiring entrepreneurs.[55] These policies have helped directly or indirectly yield better outcomes on poverty mitigation.

The economic crisis caused by the pandemic led to the partial effacing of the growth of the country that had taken place in the last few years. The pandemic led to a portion of the Indian urban population, especially in the unorganised sectors, shifting to rural areas following the lockdowns and a fall in the availability of urban employment. This led to an excess supply of workforce in the rural labour markets which were considerably subsumed by employment schemes such as MGNREGA and NRLM, ameliorating the poverty crisis to a notable extent. Table 1 depicts the massive rise in employment under MGNREGA after the initial slump during the first lockdown in March-April 2020.

Table 1: MGNREGA Employment, Covid-19 First Phase in India (in Millions)

| Months |

2019 |

2020 |

Increase |

| April |

273.94 |

141.31 |

(-) 48% |

| May |

369.52 |

568.69 |

54% |

| June |

321.43 |

640.71 |

99% |

| July |

194.17 |

391.63 |

102% |

| August |

153.05 |

238.98 |

56% |

Source: Authors’ own, data from Ministry of Rural Development, Government of India[56]

In terms of the G20, India has an important role to play here. Taking up the 2023 G20 presidency and being a key player in provision of social security for one of the world’s largest populations, Indian experience can provide useful learnings. The country has adopted various social security mechanisms, differentiated markedly by their design and mode of financing, which can be replicated by other countries and modified to suit their context and needs. While the newly revised Labour Code on Social Security has not been in operation long enough for its impact to be measured yet, India has unique social security programmes that have been running for a long time.

MGNREGA is a unique and largely successful programme, which provides assistance not just as an income, but rather as employment. In doing so, it solves the problems of targeting (by setting up a system of self-targeting) and leads to the creation of public and infrastructure assets for the places where the programme is carried out. The COVID-19 pandemic also highlighted the importance and the potential of this programme, with it serving as the only stable and alternative source of income for many, in the unprecedented absence of other informal employment largely driven by the market forces. India has also witnessed some success with scaling up voluntary financing of social security programmes. The Building and Other Construction Workers Welfare Boards have developed a system where workers were incentivised to contribute to social security by matching their contribution to that of the State’s.[57] In its ongoing G20 presidency, India has the opportunity to showcase these programmes, and other unique initiatives to lead the cause of sustainable financing of social security.

Conclusion

This paper has highlighted the imperative for providing social security to all and the gaps that exist in financing the same within and among the G20. The gaps are two-fold: between universal coverage and actual coverage, and the Global North-South divergences. The priorities and working pillars that have been put forth to guide the G20 DWG’s agenda on sustainable financing of social protection systems in its member states and the rest of the world, build upon ideas of functional cooperation between the advanced and emerging economies, based on individual country’s learnings and experiences.

First, to strengthen national social protection frameworks with universal coverage for all, it is essential to create adequate fiscal space for its provision by the State, while developing feasible and sustainable alternatives to the same. It is particularly important to consider the needs of informal workers who have traditionally been left out of the social protection net. In the absence of adequate measures, any economic, social, or environmental crisis in the future is likely to push people back into the clutches of poverty and undo the developmental progress made by countries in the past.

Second, while the need for social security will depend on local contexts, having in place a global system to resolve issues or challenges associated with the same, can strengthen the process as well as reduce regional economic disparities, thereby creating scope for development convergence. Ensuring financial sustainability of social protection is, therefore, a prerequisite that countries need to address to further their USP 2030 Agenda.

Third, apart from the politics involved, social security for poverty mitigation or advancement toward SDG 1 across the world has proven, direct implications on a variety of interlinked developmental objectives:[58] SDG 2 (Zero Hunger), SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being), SDG 4 (Quality Education), SDG 5 (Gender Equality), SDG 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation), SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy), SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth), SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities), SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities), SDG 13 (Climate Action), SDG 15 (Life on Land), and SDG 16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions).

Lastly, a close examination of the composition of social protection systems is key to ensuring their financial sustainability. The entire system should be designed with a progressive structure that enables income redistribution, guided by principles of social justice and economic efficiency. For example, some countries often introduce subsidies that benefit the well-off to a larger extent, rather than the poor. A number of social protection schemes introduced with political economy considerations have often proved to be distributionally regressive. Therefore, it is important to look closely at the composition of social expenditure to assess the desirability of different social protection schemes from a financial sustainability lens.

For emerging economies like India, harnessing its large human capital base is crucially dependent on the poverty eradication measures adopted, especially for a country that has been historically poor. Achievement of the SDG 1 objectives is crucial for a swift synchronisation between the irreconcilable trinity of sustainomics [59]—society, economy, and environment. Policies, therefore, such as MGNREGA along with the other supporting schemes that form the backbone of India’s developmental journey, can complement India’s G20 presidency on showing the way forward for sustainably financing social security measures to build long-term capacities.

(The authors acknowledge ORF interns Prarthana Vaidya and Aravind J Nampoothiry at NLSIU, Bengaluru, for their research assistance.)

Appendices

Appendix 1: SDG 1 (No Poverty) Targets

| Targets |

Objectives |

| 1.1 |

By 2030, eradicate extreme poverty for all people everywhere, currently measured as people living on less than US$ 1.25 a day. |

| 1.2 |

By 2030, reduce at least by half the proportion of men, women and children of all ages living in poverty in all its dimensions according to national definitions. |

| 1.3 |

Implement nationally appropriate social protection systems and measures for all, including floors, and by 2030 achieve substantial coverage of the poor and the vulnerable. |

| 1.4 |

By 2030, ensure that all men and women, in particular the poor and the vulnerable, have equal rights to economic resources, as well as access to basic services, ownership and control over land and other forms of property, inheritance, natural resources, appropriate new technology and financial services, including microfinance. |

| 1.5 |

By 2030, build the resilience of the poor and those in vulnerable situations and reduce their exposure and vulnerability to climate-related extreme events and other economic, social and environmental shocks and disasters. |

| 1.a |

Ensure significant mobilization of resources from a variety of sources, including through enhanced development cooperation, in order to provide adequate and predictable means for developing countries, in particular least developed countries, to implement programmes and policies to end poverty in all its dimensions. |

| 1.b |

Create sound policy frameworks at the national, regional and international levels, based on pro-poor and gender-sensitive development strategies, to support accelerated investment in poverty eradication actions. |

Source: Department of Economic and Social Affairs, United Nations[60]

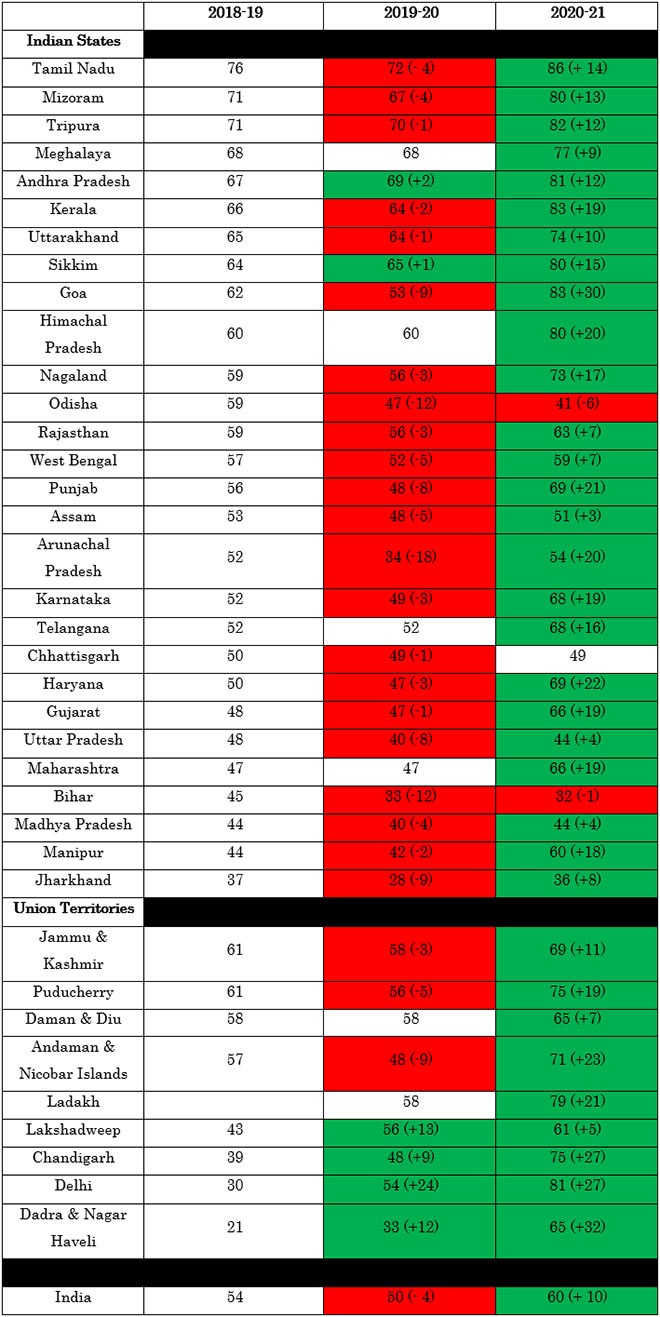

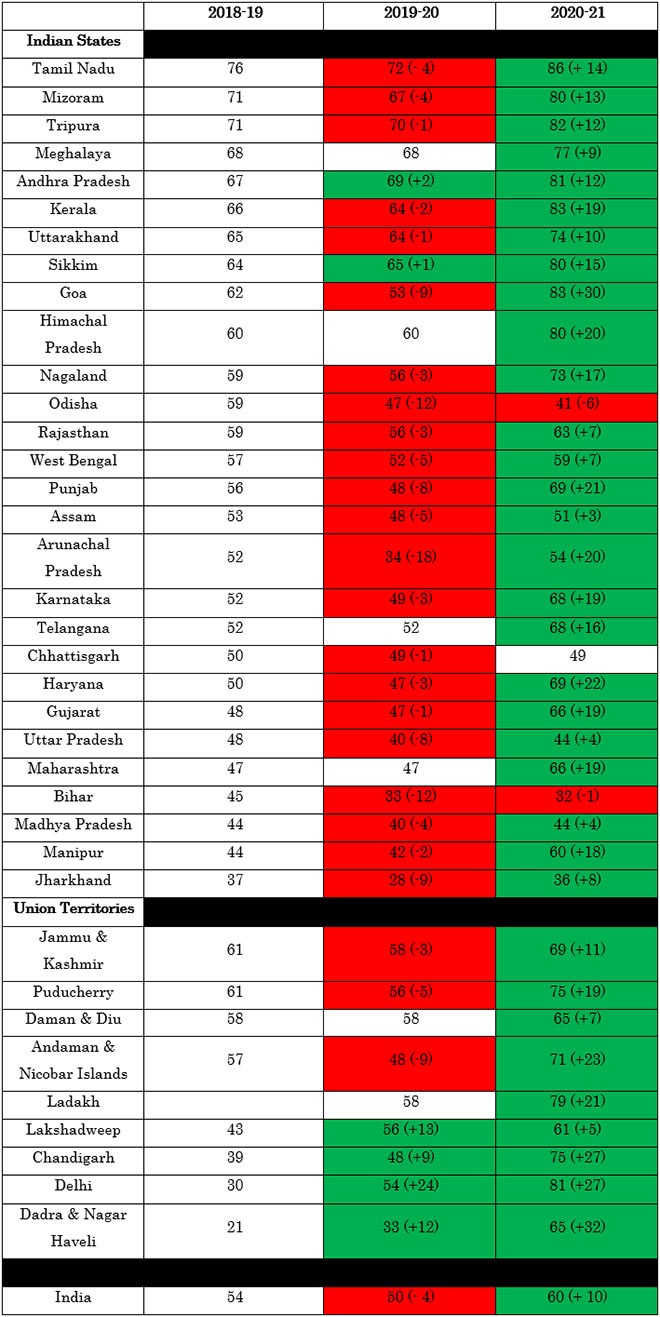

Appendix 2: Changes in SDG 1 Scores for Indian States and Union Territories (out of 100)

Source: Author’s own, data from NITI Aayog[61]

Endnotes

[a] Human Capital - to improve the conditions of the labour market, quality of life; Physical Capital - through renewed focus on markets, growth and innovation; Social Capital - enabling fair, equitable and strong societies; Natural Capital - protection, conservation and optimal use of environmental resources.

[b] Contributory Social Security Scheme presupposes a contributory relationship between the protected individual and another partner legal entity, in which social benefits apply as rights for the protected individual. Apart from these, social security financing may be non-contributory where the beneficiary does not contribute to the social security, instead the entire amount is sponsored by the State and usually funded through the public exchequer; or voluntarily financed where the State sets up a system towards which the citizens may choose to contribute.

[c] The tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority.

[d] Graduation support are livelihood promotion programmes, that can be integrated as a component of a comprehensive national social protection framework to confer livelihood security.

[1] ILO, Facts on Social Security.

[2] “Together to Achieve Universal Social Protection by 2030 (USP2030) – A Call to Action.” Global Partnership for Universal Social Protection, February 5, 2019.

[3] Mohan Munasinghe, “Sustainomics Framework.” In Sustainability in the Twenty-First Century: Applying Sustainomics to Implement the Sustainable Development Goals, 2nd ed., 26–72. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019.

[4] Mohan Munasinghe, “Sustainomics Framework.”

[5] Yogima Seth Sharma, “Over half of the world’s population, four billion, doesn’t have any social security, says ILO”, Economic Times, September 2, 2021.

[6] Yogima Seth Sharma, “Over Half the World’s Population, Four Billion, Doesn’t Have Any Social Security, Says ILO.”

[7] “Financing Social Protection through the COVID-19 Pandemic and Beyond”, ILO Report, November 25, 2021.

[8] “Financing Social Protection through the COVID-19 Pandemic and Beyond.”

[9] Simon Evans, “Nine charts to show why the G20 matters for energy and climate”, Carbon Brief, August 30, 2016.

[10] Dennis Görlich, Homi Kharas, Wilfried Rickels and Sebastian Strauss, “The Sustainable Development Agenda: Leveraging the G20 to enhance Accountability and Financing”, The G20- Insights Blog, December 10, 2020.

[11] ILO News, “ILO welcomes G20 endorsement of human-centred approach to covid-19 recovery”, International Labour Organization, October 31, 2021.

[12] “Financing Social Protection through the COVID-19 Pandemic and Beyond.”.

[13] Nicholas Freeland. “Graduation and Social Protection.” Development Pathways (blog), September 19, 2013.

[14] “ILO | Social Protection Platform,” n.d..

[15] Promoting adequate social protection and social security coverage for all workers, including those in non-standard forms of employment.

[16] Law Insider. “Contributory Social Security Scheme Definition,” n.d.

[17] “Social security and pensions”, Deloitte Perspectives, Deloitte, April 2022.

[18] Workers’ rights and social protection in Brazil, Legal and Policy gaps, OECD Watch and Conectas, March 2022.

[19] "Social security is the bedrock of South Africa’s human rights protection. But there are gaps”, The Conversation, March 18, 2022.

[20] “Employee benefits in South Africa- what’s required? What’s not?”, NKR Outsourced HR, August 5, 2019.

[21] “ILO | Social Protection Platform”

[22] Carolina Bloch. “Social Spending in South Asia—an Overview of Government Expenditure on Health, Education and Social Assistance.” International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth, September 14, 2020.

[23] “ILO | Social Protection Platform,”

[24] “ASPIRE: THE ATLAS OF SOCIAL PROTECTION - INDICATORS OF RESILIENCE AND EQUITY,” October 24, 2022.

[25] Howell H. Zee and Vito Tanzi. “Tax Policy for Emerging Markets: Developing Countries.” IMF Working Papers, Vol. 2000 (035), March 1, 2000.

[26] F. Durán Valverde, J. Pacheco-Jiménez, T. Muzaffar and H. Elizondo-Barboza, “Measuring financing gaps in social protection for achieving SDG target 1.3: Global estimates and strategies for developing countries.” Extension of Social Security Working Paper, ESS 073, International Labour Organization, November 25, 2019,

[27] “More than four billion people still lack any social protection, ILO report finds”, International Labour Organization, September 1, 2021.

[28] “Sustainable Financing - Social Protection and Human Rights,” n.d.

[29] “World Social Protection Report 2020-22: Social Protection at the Crossroads – in Pursuit of a Better Future.” International Labour Office, 2021.

[30] “More than four billion people still lack any social protection, ILO report finds”, International Labour Organization, September 1, 2021.

[31] Financing social protection through the covid-19 pandemic and beyond, International Labour Organization, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development and The World Bank, November 25, 2021.

[32] Social Protection and Climate Change.

[33] Promoting adequate social protection and social securitycoverage for all workers, including those in non-standard forms of employment.

[34] “More than 60 percent of the world’s employed population are in the informal economy”, Press Release, International Labour Organization, April 30, 2018.

[35] Debosmita Sarkar, “SDGs and Structural Vulnerabilities: The Case of BIMSTEC Countries”, ORF Occasional Paper No. 348, February 2022, Observer Research Foundation

[36] “Financing social protection through the covid-19 pandemic and beyond”

[37] Defining and Measuring Gig Work.

[38] Debosmita Sarkar and Sunaina Kumar. “Women-Centric Approaches under MUDRA Yojana: Setting G20 Priorities for the Indian Presidency.” Occasional Paper No.375, October 15 2022, Observer Research Foundation.

[39] Nicholas Freeland, “Graduation and Social Protection.”

[40] Valentina Barca and Laura Alfres, “Including informal workers within social protection systems: A summary of options”, Social Protection Approaches to COVID 19: Expert Advice, November 2021.

[41] Women and men in the informal economy: A statistical picture.

[42] Chizo Lucy Goudjo, “Financial Sustainability for social protection”, socialprotection.org, June 18, 2020.

[43] Olivia White, Anu Madgavkar, Tawanda Sibanda, Zac Townsend, and María Jesús Ramírez, “Covid 19- Making the case for robust financial infrastructure”, McKinsey Global Institute, McKinsey & Company, January 26, 2021.

[44] “Leaving No One Behind: A Social Protection Primer for Practitioners | United Nations Development Programme.” UNDP, October 6, 2016.

[45] Nilanjan Ghosh, “Promoting a ‘GDP of the Poor’: The Imperative of Integrating Ecosystems Valuation in Development Policy,” ORF Occasional Paper No. 239, March 2020, Observer Research Foundation.

[46]Rashed Al Mahmud Titumir and Md. Shah Paran. “Ecosystem Services and Well-Being in the Sundarbans of Bangladesh: A Multiple Evidence Base Trajectory.” In Assessing, Mapping and Modelling of Mangrove Ecosystem Services in the Asia-Pacific Region, edited by Rajarshi Dasgupta, Shizuka Hashimoto, and Osamu Saito, 263–81. Science for Sustainable Societies. Singapore: Springer Nature, 2022.

[47] Emil Uddhammar. “Development, Conservation and Tourism: Conflict or Symbiosis?” Review of International Political Economy 13, no. 4 (October 1, 2006): 656–78.

[48]Sunit Adhikari, Tanira Kingi, and Siva Ganesh. “Incentives for Community Participation in the Governance and Management of Common Property Resources: The Case of Community Forest Management in Nepal.” Forest Policy and Economics 44 (July 1, 2014): 1–9.

[49] Jean-Philippe Platteau. “The Gradual Erosion of the Social Security Function of Customary Land Tenure Arrangements in Lineage-Based Societies.” Working Paper. WIDER Discussion Paper, 2002.

[50] Sutirtha Sinha Roy and Roy van der Weide, “Poverty in India Has Declined over the Last Decade But Not As Much As Previously Thought,” World Bank Group, April, 2022.

[51]Surjit Bhalla, Karan Bhasin and Arvind Virmani, “Pandemic, Poverty, and Inequality: Evidence from India,” International Monetary Fund, April 5, 2022.

[52] “SDG India Index Baseline Report, 2018,” NITI Aayog, December 14, 2018.

[53] “Objective of NREGA,” State Rural Employment Society, Government of Meghalaya, India, last modified April 6, 2022.

[54] V. Suresh Babu, G. Rajani Kanth, C. Dheeraja and S.V. Rangacharyulu, “Frequently Asked Questions on MGNREGA Operations Guidelines- 2013,” Ministry of Rural Development, Department of Rural Development.

[55] “New Initiatives Schemes,” Department of Financial Services, Ministry of Finance, Government of India, last modified July 4, 2022.

[56] “Implementation of MGNREGS during COVID-19 Pandemic,” Ministry of Rural Development, Government of India, last modified September 15, 2020.

[57] “How BOCW Boards were used to help unorganized workers in Pandemic and what issues remain”, Outlook Web Desk, Outlook India, May 1, 2022.

[58] “SDG India Index Baseline Report, 2018,” NITI Aayog, December 14, 2018.

[59] Munasinghe, “Sustainomics Framework”.

[60] “Goal 1 | Department of Economic and Social Affairs”.

[61] “Reports on SDG,” NITI Aayog.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PDF Download

PDF Download

PREV

PREV