Introduction

Menstrual health is a significant public health concern in India but was largely unaddressed by governments, NGOs, and businesses until the early 2000s. Since then, India has made significant advances in ensuring good menstrual health and hygiene (MHH) for women and girls.

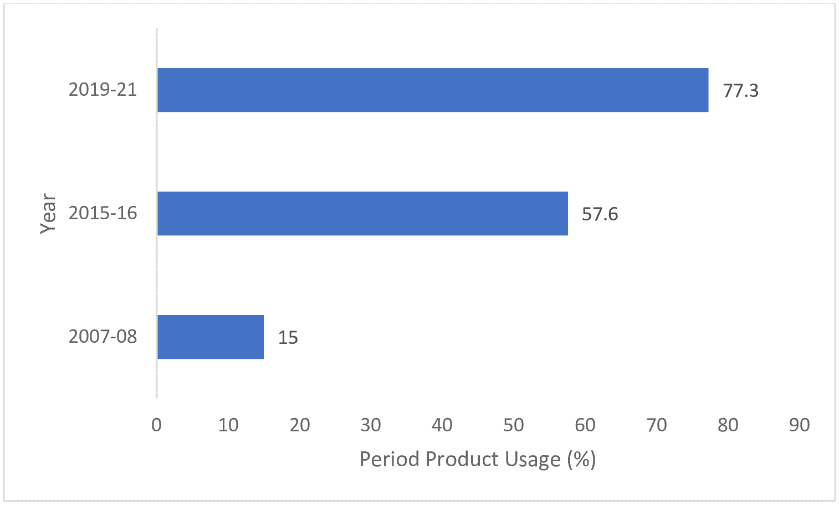

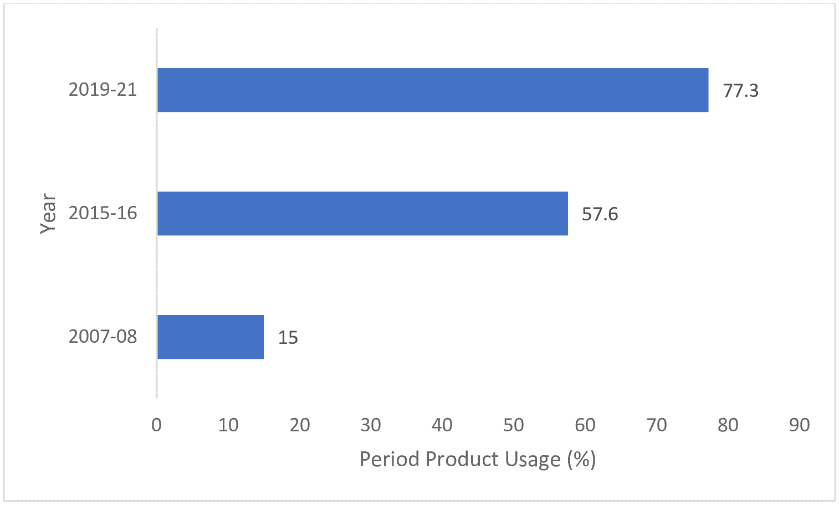

Between 2005 and 2010, the government integrated MHH into the role of Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHA) as part of the National Rural Health Mission. In 2010, India initiated the Menstrual Hygiene Scheme (MHS) to distribute sanitary napkins to young girls. The Rashtriya Kishor Swasthya Karyakram programme (under the Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, Child and Adolescent Health scheme) created further momentum by increasing awareness of and access to sanitary pads. In 2011, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare issued menstrual hygiene management guidelines; additional directions were issued by the Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation in 2015. In 2012, the Nirmal Bharat Yatra, a flagship sanitation programme that included MHH as an integral aspect of its agenda, was launched. Simultaneously, other similar programmes under the Samagra Shiksha Abhiyan began, including some geared toward promoting the installation of sanitary napkin vending machines and incinerators for safe and hygienic disposal. These initiatives have increased India’s menstrual product usage from 15 percent of menstruating women in 2010 to 57 percent in 2015–16, and further to 78 percent in 2019–21 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Period product usage in India (2007-08 to 2019-21)

Source: Karan Babbar and Supriya Garikipati

In April 2023, the Supreme Court of India advocated for a "uniform national policy" to ensure the availability of free sanitary pads for all girls in classes 6 to 12, along with the provision of separate toilets for females in all schools. In November 2023, the government indicated that a national-level menstrual hygiene policy has been formulated that seeks to break the stigma around menstruation, ensure access to period products and toilet facilities, empower women and girls, promote health and sustainability, and fulfil international commitments to gender equality and women’s well-being. While the draft policy is currently under public review, this brief discusses why the national policy should be implemented across spaces in India and not just in schools. The authors’ analysis indicates that the factors that emerge as relevant motivations for period product usage and WASH facilities can be grouped into three broad categories—affordability across demographic groups; accessibility in terms of infrastructure and support services across schools, workplaces, and public places; and socio-cultural practices and the role of awareness. Six key factors can summarise the current state of India’s menstrual policies and practices.

First, many women in India still use cloth to manage their menstrual needs. Around 80 percent of women with no schooling experience use cloth, compared to 35 percent with 12 or more years of schooling. This suggests that the number of individuals using cloth to manage their menstrual needs reduces with increased schooling.

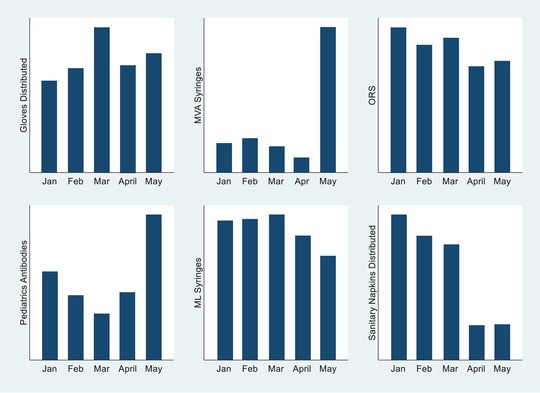

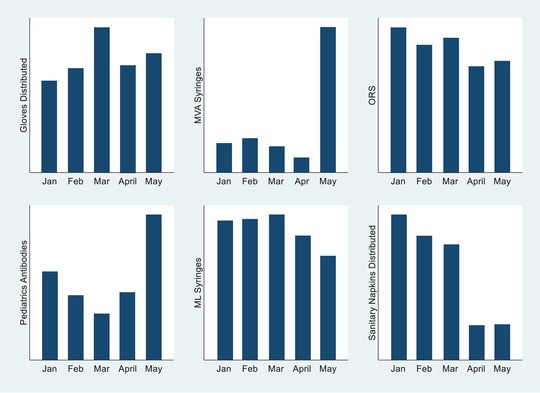

Second, period products are not a priority for many households. A recent study documents that only 40 percent of households spent money on period products before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, during which there was a 16-percent decline. The non-availability of pads during the lockdowns, disruption of sanitary pad distribution because of the mobilisation of ASHAs for pandemic-care services, loss of income during the pandemic, and the stigma associated with menstruation are factors for this decline (see Figure 2 for the levels of the various healthcare products distributed in the early months of the pandemic). The distribution of period products through government schemes saw a decline of almost 50 percent in the most impacted areas (red zones of containment) during the pandemic, while no such stark fall was seen in the distribution of other products during the same period.

Figure 2: Healthcare items distributed across India (January-May 2020)

Source: Karan Babbar, Niharika Rustagi, and Pritha Dev

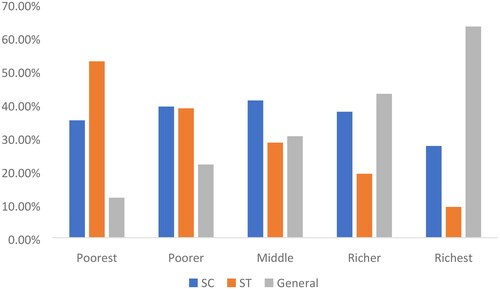

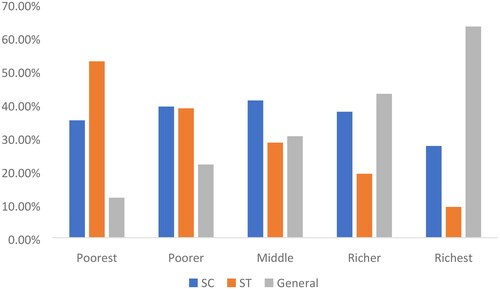

Third, although a large body of existing work focuses on wealth-based disparities (poorest to richest ratio) in the uptake of sanitary napkins, a significant policy gap exists around caste-based inequalities, particularly among marginalised individuals who menstruate (see Figure 3). As such, it is essential for policy efforts to address and rectify persisting inequalities that are deeply ingrained in societal norms and practices and continue to impact period product usage.

Figure 3: Period product usage among women across wealth index and caste

Source: Karan Babbar, Vandana, and Ashu Arora

Fourth, a significant number of girls end up missing school during menstruation due to the lack of gender-segregated washrooms and period products in schools. The lack of social support from the teaching and non-teaching staff is also a contributing factor to school absenteeism.

Fifth, a substantial portion of the population cannot afford to buy disposable period products, directly impacting India’s GDP. Throughout their lifespan, individuals with higher incomes typically use around 15,500 sanitary pads, whereas those from lower-income brackets tend to use approximately 6,600 sanitary pads. The Menstrual Health Investment Index, calculated as the cost of menstrual health management as a percentage of GDP per capita, constitutes only 1.2 percent of India's GDP per capita, Nevertheless, India has the potential to boost its GDP by 2.7 percent by tackling period poverty, understood as the “inadequate access to menstrual hygiene tools and education, including but not limited to sanitary products, washing facilities, and waste management”.

Sixth, India will not achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)—especially SDG-3 (good health and well-being), SDG-4 (quality education), SDG-5 (gender equality), and SDG-6 (clean water and sanitation)—unless it ensures menstrual health and hygiene for all the individuals who menstruate.

Developing the Menstrual Health and Hygiene Index

This brief presents options for creating a more holistic national menstrual health and hygiene policy by utilising secondary data through the National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5) 2019-2021, and analysing different socio-demographic factors that impact the usage of period products and toilets.

The NFHS data is collected through four main questionnaires: the biomarker questionnaire, which collects data on height, weight, and haemoglobin levels for children, men and women; household questionnaires, which capture information from all members of surveyed households; and separate men and women's questionnaires, designed to collect specific data from both sets of individuals within these households, covering a wide range of socio-demographic, health, and nutrition aspects. The NFHS-5 data collection took place in two phases, with Phase I occurring from June 2019 to January 2020 in 17 states and five union territories, and Phase II between January 2020 and April 2021 in 11 states and three union territories. This comprehensive survey encompassed information from a total of 636,699 households, involving 724,115 females and 101,839 males.[i] This brief focuses on menstruation-related questions from the NFHS-5 dataset, specifically analysing the responses of 241,112 women aged between 15 and 24 years, making them the sample for this brief.

Measures

· Dependent Variable

This brief considers two questions to identify the dependent variable pertaining to MHH:

1. “Women use different methods of protection during their menstrual period to prevent blood stains from becoming evident. What do you use for protection, if anything? Anything else?” The response options ranged from 1 for cloth, 2 for locally prepared napkins, 3 for sanitary napkins, 4 for tampons, 5 for nothing, and 6 for other. The authors defined women who use menstrual cups, tampons, locally produced napkins, and sanitary napkins as using period products and women using cloth, other objects, or nothing at all as not period products.[ii] This renders the variable binary, and the authors denote as period product usage, coded as 1, if women use period products, and 0 otherwise.

2. The second variable of interest is the toilet facility. The authors coded this variable as 1 if the toilet facility falls under any of the following categories: a) flush—to piped sewer system; b) flush—to septic tank; c) flush—to pit latrine; d) flush—don’t know where; e) pit latrine—ventilated improved pit (VIP); f) pit latrine—with slab; g) composting toilet; and 0 otherwise.

As such, the authors constructed a composite index called the ‘Menstrual Health and Hygiene (MHH) Index’ taking the value 1, only if both period product usage and toilet facility equal 1, and 0 otherwise.

· Independent Variables

Based on the existing literature,[iii],[iv],[v],[vi],[vii],[viii] the authors selected multiple individual and household-level variables that account for the income/wealth, awareness, and sociocultural contexts for our analysis. Individual variables include education (no education, primary, secondary, higher), and the frequency of reading the newspaper, listening to the radio and watching television (not at all, less than once a week, at least once every week). The authors combined the variables of the frequency of reading the newspapers, listening to the radio, and watching television to create a new variable—mass media exposure. The authors gave the value 0 if a respondent has no exposure to any form of media, and 1 or 2 if the respondent has exposure to media less than once a week or at least once a week, respectively.

Household-level variables include wealth index (poor, middle, rich), social groups (scheduled caste, scheduled tribe, other backward classes, none/do not know), religion (Hindu, Muslim, others), and place of residence (urban, rural).

Empirical Strategy

The authors analysed the descriptive statistics of the variables chosen to offer a comprehensive understanding of the various socio-demographic factors influencing the MHH Index. These statistics provide a clear overview of patterns and trends and largely align with the Supreme Court’s primary objective. First, the authors presented the characteristics of women and girls aged 15 to 24 at the individual and household levels. Subsequently, the authors focused on the primary variable of interest, the MHH Index, and demonstrated its determinants and prevalence using background characteristics in a table (see Table 1). The authors performed Chi-square tests to examine the significant differences that exist across the categories of the critical predictors.

Results

Table 1 presents the descriptive summaries. Column 1 (overall sample) shows that the majority of the sample lives in rural regions (71 percent) and is Hindu (80 percent). Further, around 45 percent of them fall under the category of other disadvantaged groups. About 87 percent of the women have completed at least secondary school. Merely 58 percent are heavily exposed to mass media.

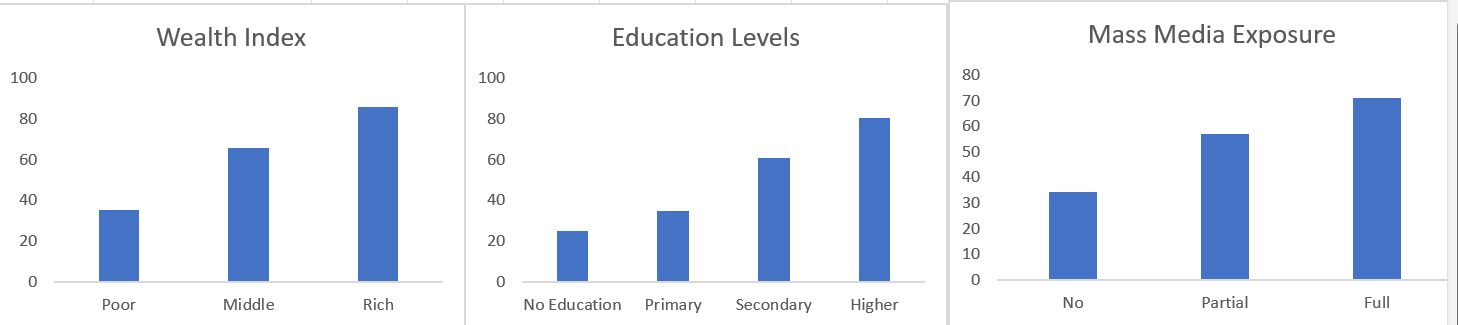

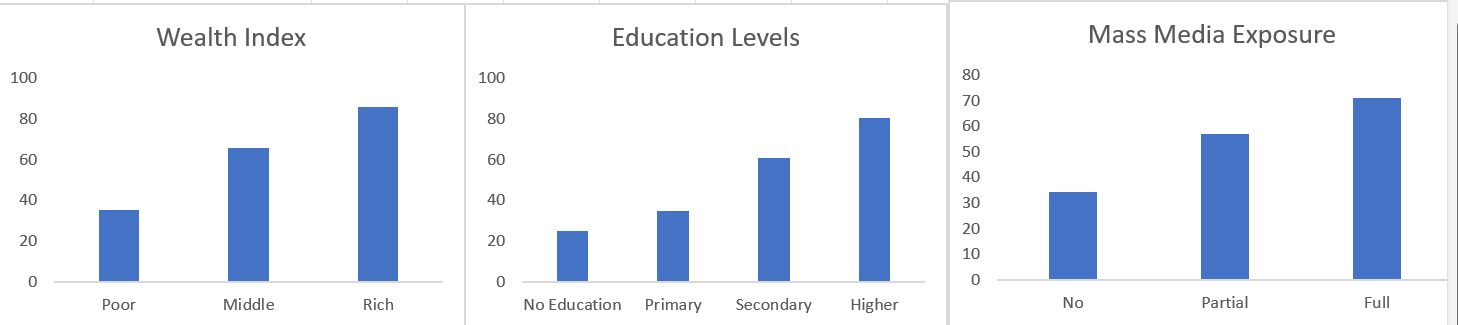

Column 2 highlights the prevalence of the MHH Index based on the background factors. Higher levels of education are associated with a higher proportion of women and girls having elevated MHH indices. Additionally, women with frequent media exposure exhibit a higher MHH Index. The MHH Index also increases with increasing wealth and urban residence. Among social categories, individuals in the general category have the highest MHH Index, followed by those in other backward classes, scheduled castes, and scheduled tribes. Women belonging to other religions have the highest MHH Index, followed by Hindus and Muslims.

Table 1. Respondent’s characteristics and prevalence of MHH by background characteristics of women aged 15-24

|

Respondent Characteristics

|

Overall Sample

|

MHH Index

|

p-value

|

|

|

Variables

|

Frequency (percent)

|

Prevalence (percent)

|

|

|

Individual Level

|

|

|

|

|

|

Education

|

|

|

|

|

|

No Education

|

16010 (6.51)

|

3900 (24.83)

|

<0.01

|

|

|

Primary

|

15002 (6.23)

|

5192 (34.55)

|

|

|

Secondary

|

168132 (68.24)

|

100020 (60.78)

|

|

|

Higher

|

41956 (19.02)

|

36845 (80.33)

|

|

|

Mass media Exposure

|

|

|

|

|

|

No

|

49250 (19.76)

|

16393 (34.40)

|

<0.01

|

|

|

Partial

|

57698 (22.59)

|

30995 (56.89)

|

|

|

Full

|

134232 (57.65)

|

98569 (70.90)

|

|

|

Household Level

|

|

Wealth Index

|

|

|

|

|

|

Poor

|

110273 (41.94)

|

35820 (35.42)

|

<0.01

|

|

|

Middle

|

51275 (21.01)

|

33382 (65.89)

|

|

|

Rich

|

79632 (37.06)

|

76754 (85.88)

|

|

|

Social Category

|

|

|

|

|

|

General

|

41045 (19.68)

|

33260 (73.56)

|

<0.01

|

|

|

Scheduled Caste

|

49136 (24.04)

|

30829 (55.83)

|

|

|

Scheduled Tribe

|

44392 (10.09)

|

9827 (42.20)

|

|

|

Other Backward Classes

|

93969 (45.52)

|

63883 (61.10)

|

|

|

Don't Know/Unknown

|

1167 (0.67)

|

673 (43.85)

|

|

|

Religion

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hindu

|

181475 (80.31)

|

114612 (59.17)

|

<0.01

|

|

|

Muslim

|

33773 (15.24)

|

23305 (63.40)

|

|

|

Others

|

25932 (4.45)

|

8040 (74.96)

|

|

|

Place of Residence

|

|

|

|

|

|

Urban

|

54561 (29.42)

|

56404 (79.60)

|

<0.01

|

|

|

Rural

|

186619 (70.58)

|

89553 (52.58)

|

|

|

Note: The prevalence of MHH Index in column 2 refers to the percentage of women who have access to both period products and a hygienic toilet facility. The total number of observations for all variables is 241,180, except for the ‘Social Category', where the number of observations is 229,709 on account of missing observations.

|

Source: NFHS-5 (2019-21)

Figure 4 displays the MHH Index by wealth index, education levels, and mass-media exposure.

Figure 4: MHH Index by wealth index, education levels, and mass-media exposure

Source: Authors’ assessments

Recommendations

The MHH Index assesses the accessibility of sanitary pads and toilets for girls and women across India. The findings highlight the necessity for policy initiatives to extend their focus to individuals who menstruate and belong to poor socioeconomic backgrounds, reside in rural areas, and have lower levels of media exposure and education. Based on the index and previous literature, the following best practices and recommendations can be considered to develop a holistic menstrual health policy.

Initiating awareness campaigns and behavioural interventions

MHH is a multifaceted concept, and the mere provision of sanitary pads and toilet facilities falls short of truly comprehensive support. Given the importance of exposure to information through mass media about period products, equipping individuals with the knowledge of how to use period products is vital. Therefore, educational interventions within schools for all genders will be an essential neutral approach in this direction. These interventions will improve the understanding of menstruation among schoolgirls, will help dispel the taboos and myths around menstruation, and will start conversations around the menstrual cycle, family planning, and ways to mitigate infections., Integrating conversations around menstruation into the daily lives of young students can foster safe environments where peers provide enhanced social support to each other. In addition, extending such interventions to the broader community will ensure that discussions about menstruation become commonplace and result in improved social support across the board.

Mandating the provision of menstrual health support in workplaces

In addition to supporting schoolgirls, it is also essential to support menstruating individuals aged 18 years and more. While many organisations have diversity and inclusion policies in the workplace, there is scope for significant improvements. The national menstrual health policy can mandate the provision of menstrual health support at the workplace. Menstrual health support requires ensuring a variety of period products available for all individuals who menstruate, as well as a proper disposal facility arranged in female and gender-neutral toilets. Lastly, workplaces should also have a counsellor to provide sufficient mental health support to the individuals experiencing menses.

Individuals who menstruate and work in informal settings (for instance, construction workers) often lack access to clean sanitation facilities and period products. The national policy should strongly advocate to ensure that all the workspaces provide individuals who menstruate their human right to menstruate in dignity.

Tailoring solutions to local contexts

While a uniform national policy document highlights the necessity for a standardised approach to menstrual health, encompassing interventions beyond period products and WASH facilities to adequately account for local contexts is also essential. With wide cultural and regional variation in India, an approach that excels in one community may not yield the same results in another. As such, initiating localised pilot studies across diverse regions might be prudent. These studies could generate evidence to inform the implementation of policies across different states.

A potential approach in this regard will involve decentralising the national policy, granting states the autonomy to determine the most appropriate course of action regarding specific measures while ensuring the provision of period products and WASH facilities. This way, the policy can effectively address local challenges, maximise impact, and promote a more tailored approach that resonates with the needs of each region. Decisions on a standardised approach to menstrual health should be guided by specific interventions and initiatives in pilot cities and states before they are implemented on a larger scale. Community-based approaches could also be adopted to scale up and harness the power of local knowledge, resources, and networks to ensure the sustainable expansion of menstrual health initiatives.

Establishing a central agency for menstrual health

Menstrual health is linked with health, education, gender equality, environment, climate change, and many other issues. Therefore, relying on a single ministry to handle the domain of menstrual health may be insufficient. It is crucial to establish a central agency responsible for menstrual health initiatives, and this endeavour should be a collaborative effort involving various other agencies. While a central agency is crucial, it is equally important to consider the local context, which varies from one district to another at more granular levels. As such, it is imperative to involve state and district-level administrators from the relevant departments as stakeholders before implementing interventions or policies at these levels.

Widening the target population

Ensuring menstrual support for out-of-school girls within the same age group is equally essential, yet policy is silent on the matter. The national policy should extend some support to individuals who menstruate beyond the completion of school, given that many recipients of sanitary pads at the school level are economically disadvantaged. Once these individuals finish schooling, accessing period products may become a challenge and impact their ability to manage menstrual needs and be effectively and continuously employed in the labour force.

Improving the quality of pads

Anecdotal evidence available through media reports suggests that the free sanitary pads provided by the government do not last across all the days of the menstrual cycle, thus raising concerns about the low-absorbent capacity and small size of the pads. Besides enhancing the accessibility of sanitary pads, the quality of affordable sanitary pads is crucial to addressing menstrual health challenges effectively. The affordability of quality products remains the primary barrier to pad usage, and improving this aspect is essential for effective MHH management.

Ensuring environmental sustainability

In India, an estimated 12 billion pads are used annually, resulting in an estimated 9,400 tonnes of menstrual waste per month (or 112,800 tonnes annually). As such, it is crucial that the policy recognises and encourages reusable period products such as cloth pads and menstrual cups. An essential step in this direction would be to subsidise environmentally friendly alternatives, or even provide them freely to the target population. In addition, the government should invest in educating the population about the various period products available in the market so that individuals who menstruate can make informed and environmentally friendly choices based on their needs. Policymakers must also prioritise educating individuals who menstruate on how to create and reuse cloth pads. This knowledge will equip them to prepare for the potential unavailability of period products, as seen during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Ensuring the inclusion of transgender and non-binary individuals

The draft national policy excluded transgender and non-binary individuals who menstruate. While India officially recognises transgender individuals as a third gender, the policy does not encompass provisions for these individuals enrolled in schools. There is a need for appropriate infrastructure for them to access free period products and dedicated toilet facilities. In addition to providing sufficient infrastructure, there needs to be more support for trans and non-binary individuals who menstruate. This support can be provided through training teaching and non-teaching staff along with the students, including trans and non-binary students who menstruate, to normalise the conversations around menstruation. In this regard, there are a few concerns about the existing norms that must be overcome. First, the term ‘menstruators’ is often used to refer to all the individuals who menstruate. However, this term dehumanises menstruation and reduces these individuals to their bodies and bodily functions. The authors propose using the term ‘individuals who menstruate’ to accommodate all individuals who menstruate, thus removing the burden of gender and gender identity. Second, period products are often labelled as women's hygienic products, which often exclude trans and non-binary communities and may create gender dysphoria. As such, it is essential to transition towards a gender-neutral term to refer to a standard set of products used to manage periods. Such initiatives can help reshape the social narrative to one that reduces the stigma associated with menstruation and its target population.

Conclusion

This brief provides an overview of the status of MHH management and practices in the country and emphasises that a uniform national policy is the need of the hour. While the government’s draft national policy on menstruation is welcome, there is potential for it to be more transformative by considering and including all individuals who menstruate across their lifespan. The research indicates significant disparities in the MHH Index based on factors such as education levels, economic status, and media exposure among women. The findings from the MHH Index, combined with existing literature, highlight the need for more impactful initiatives. Awareness campaigns and educational interventions, particularly within educational institutions and workplaces, are pivotal tools to dispel taboos and encourage open dialogues surrounding menstruation. Further recommendations include adapting solutions to local contexts through pilot studies and establishing a central agency. These proposed initiatives showcase a commitment to addressing the diverse challenges prevalent in the Indian landscape. By incorporating inclusive measures and addressing disparities, the proposed initiatives aim to establish a more holistic menstrual hygiene policy, with a transformative impact on menstrual health management practices across India.

Endnotes

1.Sunaina Kumar, “Menstrual health in India needs more than just distribution of low cost sanitarypads,” ORF, 11 November 2020. https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/menstrual-health-in-india-needs-more-than-just-distribution-of-low-cost-sanitary-pads/

2. Facility Survey (DLHS 3) 2007–08: fact sheets India, States and Union Territories, IIPS District LevelHousehold, (Mumbai: International Institute of Population Sciences, 2010).

3. National Family Health Survey (NFHS - 4), 2015–16 INDIA REPORT, (Mumbai: IIPS and MacroInternational 2017). https://doi.org/kwm120 [pii]10.1093/aje/kwm120

4. National Family Health Survey (NFHS - 5), 2019–21 INDIA REPORT, (Mumbai: IIPS and MacroInternational 2022). http://rchiips.org/nfhs/NFHS-5Reports/NFHS-5_INDIA_REPORT.pdf

5. Karan Babbar and Supriya Garikipati, "What socio-demographic factors support disposable vs.sustainable menstrual choices? Evidence from India’s National Family Health Survey-5; PLOS One18, no. 8 (2023): e0290350. https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0290350

6. Padmakshi Sharma, “National Policy On Menstrual Hygiene : Supreme Court Warns States &; UTs

Which Haven't Filed Responses”, Live Law, 25 July 2023. https://www.livelaw.in/top-

stories/supreme-court-directs-states-uts-to-file-responses-in-plea-to-frame-national-policy-on-

menstrual-hygiene-by-august-31-233534 .

7. Read Draft Menstrual Hygiene Policy at

https://main.mohfw.gov.in/sites/default/files/Draft%20Menstrual%20Hygiene%20Policy%202023%

20-For%20Comments.pdf

8. National Family Health Survey (NFHS - 5), 2019–21 INDIA REPORT, (Mumbai: IIPS and Macro

International 2022), http://rchiips.org/nfhs/NFHS-5Reports/NFHS-5_INDIA_REPORT.pdf

9. Karan Babbar and Pritha Dev, "Period products during the pandemic: The impact of lockdown on

period products usage; Applied Economics (2023): 1-17.

https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2023.2257035

10. Karan Babbar, Niharika Rustagi, and Pritha Dev, "How COVID‐19 lockdown has impacted the

sanitary pads distribution among adolescent girls and women in India," Journal of Social Issues 79,

no. 2 (2023): 578-595. https://doi.org/10.1111/JOSI.12533

11. Karan Babbar, Niharika Rustagi, and Pritha Dev, "How COVID‐19 lockdown has impacted the

sanitary pads distribution among adolescent girls and women in India," Journal of Social Issues 79,

no. 2 (2023): 578-595. https://doi.org/10.1111/JOSI.12533

12. Aditya Singh, Mahashweta Chakrabarty, Shivani Singh, Diwakar Mohan, Rakesh Chandra, and

Sourav Chowdhury;Wealth-based inequality in the exclusive use of hygienic materials during

menstruation among young women in urban India; PloS one 17, no. 11 (2022): e0277095.

https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0277095

13. Karan Babbar, Vandana, and Ashu Arora;Bleeding at the margins: Understanding period poverty

among SC and ST women using decomposition analysis," The Journal of Development Studies (2023):

1-16. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2023.2252139

14. Karan Babbar, Vandana, and Ashu Arora;Bleeding at the margins: Understanding period poverty

among SC and ST women using decomposition analysis," The Journal of Development Studies (2023):

1-16. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2023.2252139

15. Julie Hennegan, Alexandra K. Shannon, Jennifer Rubli, Kellogg J. Schwab, and G. J. Melendez-

Torres;Women’s and girls’ experiences of menstruation in low-and middle-income countries: A

systematic review and qualitative metasynthesis ;PLoS medicine 16, no. 5 (2019): e1002803.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002803

16. Tanya Narang, ”Addressing Period Poverty Can Boost India’s GDP By 2.7%: Insights & Economic

Implications,”20 September 2022. https://mpra.ub.uni-

muenchen.de/114660/1/MPRA_paper_114660.pdf

17. Tanya Narang, ”Addressing Period Poverty Can Boost India’s GDP By 2.7%: Insights & Economic

Implications,”20 September 2022. https://mpra.ub.uni-

muenchen.de/114660/1/MPRA_paper_114660.pdf

18. Alexandra Alvarez, Period poverty, American Medical Women’s Association, 31 October 2019.

https://www.amwa-doc.org/period-poverty/

19. United Nations, General Assembly, “Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable

Development. Resolution adopted by the General Assembly”, Governing Through Goals: Sustainable

Development Goals as Governance Innovation, 25 September 2015.

https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/9780262035620.003.0011

20. National Family Health Survey (NFHS - 5), 2019–21 INDIA REPORT, (Mumbai: IIPS and Macro

International 2022). http://rchiips.org/nfhs/NFHS-5Reports/NFHS-5_INDIA_REPORT.pdf

21. National Family Health Survey (NFHS - 5), 2019–21 INDIA REPORT, (Mumbai: IIPS and Macro

International 2022). http://rchiips.org/nfhs/NFHS-5Reports/NFHS-5_INDIA_REPORT.pdf

22. Alejandra Almeida-Velasco and Muthusamy Sivakami, "Menstrual hygiene management and

reproductive tract infections: a comparison between rural and urban India," Waterlines 38, no. 2

(2019): 94-112. https://doi.org/10.3362/1756-3488.18-00032

23. Enu Anand, Jayakant Singh, and Sayeed Unisa, "Menstrual hygiene practices and its association

with reproductive tract infections and abnormal vaginal discharge among women in India; Sexual &

Reproductive Healthcare 6, no. 4 (2015): 249-254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.srhc.2015.06.001

24. Karan Babbar, Deepika Saluja, and Muthusamy Sivakami, “How socio-demographic and mass

media factors affect sanitary item usage among women in rural and urban India,” Waterlines 40, no.

3 (2021): 160-178. https://doi.org/10.3362/1756-3488.21-00003

25. Srinivas Goli, Nowaj Sharif, Samanwita Paul, and Pradeep S. Salve, "Geographical disparity and

socio-demographic correlates of menstrual absorbent use in India: A cross-sectional study of girls

aged 15–24 years; Children and Youth Services Review 117 (2020): 105283.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105283

26. Aditya Singh, and Mahashweta Chakrabarty, "Spatial heterogeneity in the exclusive use of hygienic

materials during menstruation among women in urban India; PeerJ 11 (2023): e15026.

https://doi.org/10.7717/PEERJ.15026

27. Karan Babbar, Vandana, and Ashu Arora, "Bleeding at the margins: Understanding period poverty

among SC and ST women using decomposition analysis," The Journal of Development Studies (2023):

1-16. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2023.2252139

28. Enu Anand, Jayakant Singh, and Sayeed Unisa, "Menstrual hygiene practices and its association

with reproductive tract infections and abnormal vaginal discharge among women in India; Sexual &

Reproductive Healthcare 6, no. 4 (2015): 249-254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.srhc.2015.06.001

29. Karan Babbar and M Sivakami, “Promoting Menstrual Health: Towards Sexual and Reproductive

Health for All,” ORF Issue Brief No. 613, February 2023, Observer Research Foundation.

https://orfonline.org/research/promoting-menstrual-health

30. Karan Babbar and Deepika Saluja, "Changing The Narrative Of Women’s Menstrual Hygiene: RIO

Pads; Asmita Plus;, Feminism in India, 5 February 2021.

https://feminisminindia.com/2021/02/05/menstrual-health-rio-pads-asmita-plus/

31. Gautami Bhor and Sayali Ponkshe;A decentralized and sustainable solution to the problems of

dumping menstrual waste into landfills and related health hazards in India; European Journal of

Sustainable Development 7, no. 3 (2018): 334-334.

32. Karan Babbar, Jennifer Martin, Pratyusha Varanasi, and Ivett Avendaño, "Inclusion means

everyone: standing up for transgender and non-binary individuals who menstruate worldwide; The

Lancet Regional Health-Southeast Asia 13 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.LANSEA.2023.100177

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PDF Download

PDF Download

PREV

PREV