-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

PDF Download

PDF Download

Girish Luthra, “The Russia-Ukraine Conflict and Sanctions: An Assessment of the Economic and Political Impacts,” ORF Occasional Paper No. 374, October 2022, Observer Research Foundation.

Introduction

The use of economic instruments to pursue political objectives has long been a part of statecraft, although the methods of their deployment have continuously evolved. In the twentieth century, the practice of using economic sanctions—broadly, the withdrawal of trade and financial arrangements for foreign policy purposes—took shape during the First World War. The concept was inspired by the extensive use of wartime blockades and embargoes, and was formally incorporated into the Covenant of the League of Nations (Article 16) in 1919. Termed the ‘economic weapon’, sanctions were envisioned as an antidote to war.[1]

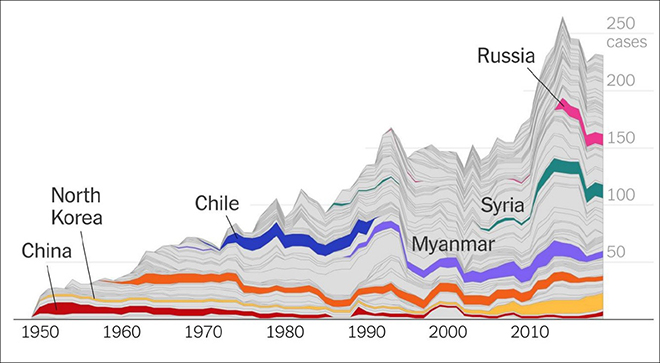

During the inter-war period, sanctions were used—with limited success—as a key tool for deterrence and played a major role in shaping the new liberal internationalism. Sanctions measures were retained under Article 41 of the United Nations (UN) Charter,[2] thereby perpetuating their legitimacy and legality.[3] Although the usage of economic sanctions was normalised gradually during the Cold War, it was the post-Cold War period that saw a dramatic increase in their use, particularly by the US (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Cases of Economic Sanctions (1950- 2019)

The efficacy and effectiveness of modern economic sanctions have been debated for years. Sanctions have been analysed extensively to determine their success or failure in achieving the intended political outcomes. Many have argued that sanctions, particularly unilateral sanctions, rarely work, are immoral in many cases, and can have numerous unintended consequences.[5] Additionally, some have suggested that economic sanctions have limited usefulness, given that modern states are less fragile and vulnerable.[6] At the same time, supporters of sanctions argue that such measures should be viewed as a distinct policy alternative, and that they may serve little purpose if viewed from the prism of success or failure without a comparative analysis with other alternatives.[7] Notably, it is hard to assess the effectiveness of economic sanctions as they have become a complementary policy tool and are rarely applied in isolation.[8]

Amid the ongoing Russia-Ukraine war, several countries have applied an extremely high scale and range of economic sanctions against Russia. The effects of these sanctions in the war zone, in neighbouring areas, and at the global level are still unfolding. While sanctions have been applied against Russia on different occasions in the post-Second World War period, this paper examines the broad economic and political impact of economic sanctions used in the context of the Russia-Ukraine conflict. This assessment relates to sanctions used initially in 2014 in the aftermath of Russia’s annexation of Crimea and other activities in eastern Ukraine, incremental increases in the 2014-21 period, and the new range of sanctions imposed during the ongoing war (between February 2022 to September 2022). This paper does not seek to analyse the success or failure of these economic sanctions.

Economic Sanctions Imposed on Russia Between 2014 and 2021

Territorial claims in eastern Europe have a long historical context, but there has been a major disagreement between the West and Russia over the European security architecture since the end of the Cold War. The gradual expansion of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) was problematic for Russia, and Russian President Vladimir Putin had long felt that the West had been promoting the evolution of a Ukrainian national identity as part of its geopolitical ambitions against Russia.[9] In 2008, the European Union (EU) launched the Eastern Partnership, an economic cooperation arrangement with Eastern European countries and which provided the basis for the Association Agreement.[a] In November 2013, Ukraine, under then President Viktor Yanukovych, refused to sign the Association Agreement for trade with the EU. Russia extended a loan to Ukraine as an alternative in December 2013, which led to protests in Kyiv (the Ukrainian capital), commonly referred to as the Maidan Uprising.[b] On 22 February 2014, Yanukovych was ousted, and an interim government was established. Russia claimed that the overthrow was engineered by the West, while the EU and the US maintained that it was due to the popular uprising and the use of force by the Yanukovych government to suppress the protests. Five days later, on 27 February, Russia’s special teams took control of the airport at Sevastopol in Crimea. Parts of the Luhansk and Donetsk oblasts (provinces), which make up the Donbas region in eastern Ukraine, declared independence from the country and formed the Luhansk People’s Republic and the Donetsk People’s Republic. By mid-March 2014, Russia took full control of Crimea and installed a new government. Subsequently, Russian special teams also moved into the Donbas region.

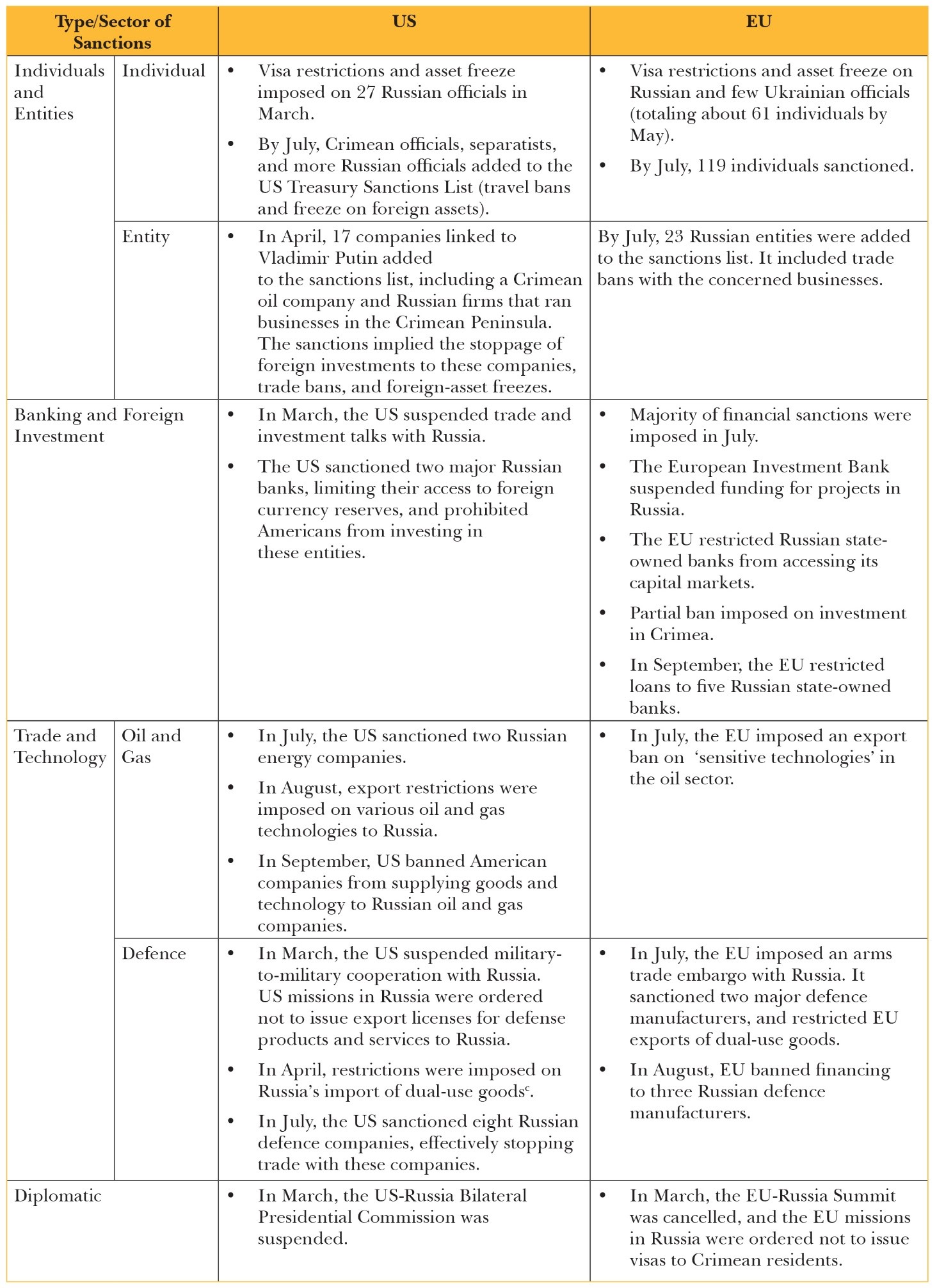

In March 2014, the US and the EU imposed targeted economic sanctions against Russia due to its annexation of Crimea and actions in eastern Ukraine. The sanctions were initially focused on individuals and businesses related to Crimea and eastern Ukraine but were gradually expanded during the year to other entities and sectors of the Russian economy. The sanction regimes of the US and the EU were broadly similar, focusing on individuals and entities in the financial, oil and gas, defence, and technology sectors (see Table 1). They were targeted at the core of the Russian economy to impose costs, while minimising the potential adverse impact on the EU and the US economies. This was particularly relevant for the EU, since 53 percent of Russia’s exports and 46 percent of its imports of goods in 2013 were to/from the EU, and 75 percent of Russia’s foreign bank loans were held with European banks.[10] Caution was exercised since economic sanctions were being imposed against a major world economy after many decades, and it was imperative to limit their fall on the sender countries (countries imposing the sanctions).

The sanctions imposed by the US and EU against Russia did not have the UN’s mandate, although the UN General Assembly adopted a resolution on Ukraine’s territorial integrity and requested the international community to not recognise the illegal annexation of Crimea.[11]

Table 1: Overview of US and EU Sanctions on Russia (Imposed in 2014)

Russia announced countersanctions in August 2014, which primarily focused on banning the import of specific food and farm items from the EU and the US. It also banned certain individuals from travelling to Russia. It employed countersanctions on food items more as part of a plan to become self-dependent rather than to target others, and planned import substitution to overcome any major food shortages.

Between 2015 and 2021, the US gradually strengthened the sanctions it had imposed in 2014. The sanctions regime was also expanded to cover a wider range of objectives, including the alleged Russian interference in the US election process, malicious cyber activities, human rights abuses, alleged use of chemical weapons, weapons proliferation, illicit trade with North Korea, and support to Syria and Venezuela.[13] In 2017, the US codified the four presidential executive orders from 2014 on sanctions related to Ukraine through the Countering Russian Influence in Europe and Eurasia Act, as a part of the broader Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act.[14] In 2020, the US prohibited trade related to the development of Russian deep-water, Arctic offshore, and shale projects that have the potential to produce oil.[15]

In parallel with the sanctions process in 2014, the EU suspended preparations for the G8 summit, which was scheduled in Sochi, Russia, in June. That same year, Russia was also dropped from the G8, and discussions to include it in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development were suspended.[16] The EU determined the specific steps Russia would need to take for de-escalation, and signed the Association Agreement with Ukraine, Georgia, and Moldova in 2014. In February 2015, the EU announced its support for the Minsk Agreements[c] and, thereafter, decided to align the sanctions regime to the implementation of those agreements. The European Council periodically extended and expanded the scope of the 2014 sanctions over the following years. In March 2019, the EU responded to escalation in the Kerch Strait and the Sea of Azov by imposing additional sanctions on individuals and entities.[17]

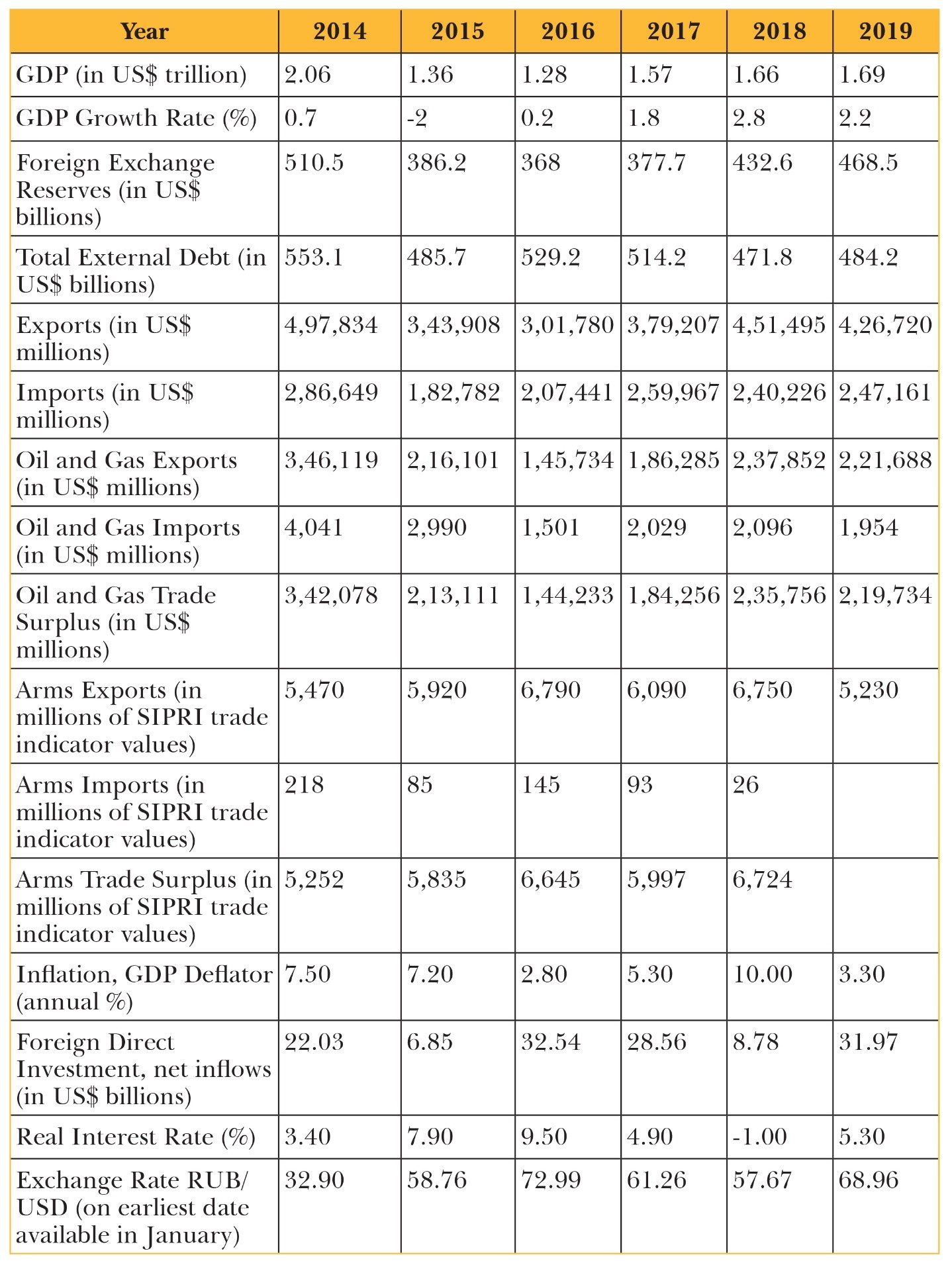

Table 2: Key Indicators of Russian Economy (2014-2019)

Russian foreign debt declined from US$553.1 billion in 2014 to US$484.24 billion in 2019, as western banks and financial institutions imposed credit restrictions, and debt refinancing became increasing difficult for the sanctioned Russian companies.[23] The Russian economy was impacted due to drop in foreign direct investment (FDI) and reduced access to foreign capital, with one study estimating the combined loss at US$648 billion (US$479 billion due to loss of credit, US$169 billion due to loss of FDI) during the 2014-2020 period.[24] These losses were accompanied by strong capital outflows and a cautious macroeconomic policy, forcing the Russian government to raise taxes and cut public spending. This allowed the Russian leadership to justify its policy moves towards a more centralised political economy.[25] At the same time, Russia also emphasised that the economic impact of sanctions had been negligible, with low inflation, low foreign debt, healthy current account surpluses, and strong international currency reserves.

Overall, the sanctions had an adverse (but not very severe) impact on the Russian economy. This also enabled Russia to work on minimising its economic vulnerabilities against a full set of sanctions in the future.[32] At the political level, the impact was negligible. Popular support in Russia for Putin’s posture remained strong, while the effectual international isolation of Russia was not achieved.[33] The sanctions delayed a full-scale war but could not deter it.

Economic Sanctions Against Russia in 2022

In September 2021, the US and Ukraine issued a Joint Statement on Strategic Partnership,[34] which included a commitment to deepen security and defence cooperation, hold Russia accountable for its aggression, support Ukraine’s Euro-Atlantic aspirations, and provide Ukraine with security assistance. Soon thereafter, there were indications that Russia was preparing to threaten the use of force. Hectic diplomatic parleys between the western countries and Russia to find a solution and prevent war made little headway. To deter Russia, the US announced on 25 January 2022 that it, and its allies and partners, were ready to impose “severe” economic sanctions against Russia if it further invades Ukraine, and that these sanctions will start at the “top of the escalation ladder and stay there”.[35] The threat of sanctions was repeated at different fora, including at the Munich Security Conference held on 19 February.[36] The roll out of sanctions by the US, the EU, the UK, and a few other partners began on 21 February, after Putin signed a decree recognising the independence and sovereignty of the Luhansk and Donetsk regions. On 24 February, Russian forces invaded Ukraine, announced by Putin in his “on conducting a special military operation” televised address that gave a detailed rationale for the Russian military operations.[37] He highlighted that a hostile post-Cold War international architecture shaped by the US, the sustained eastward expansion by NATO, and external support to an unfriendly Ukraine left Russia with no choice but to take military action. He stated that the objective of the military operations was “to protect people who, for eight years now, have been facing humiliation and genocide perpetrated by the Kiev regime. To this end, we will seek to demilitarize and denazify Ukraine”.

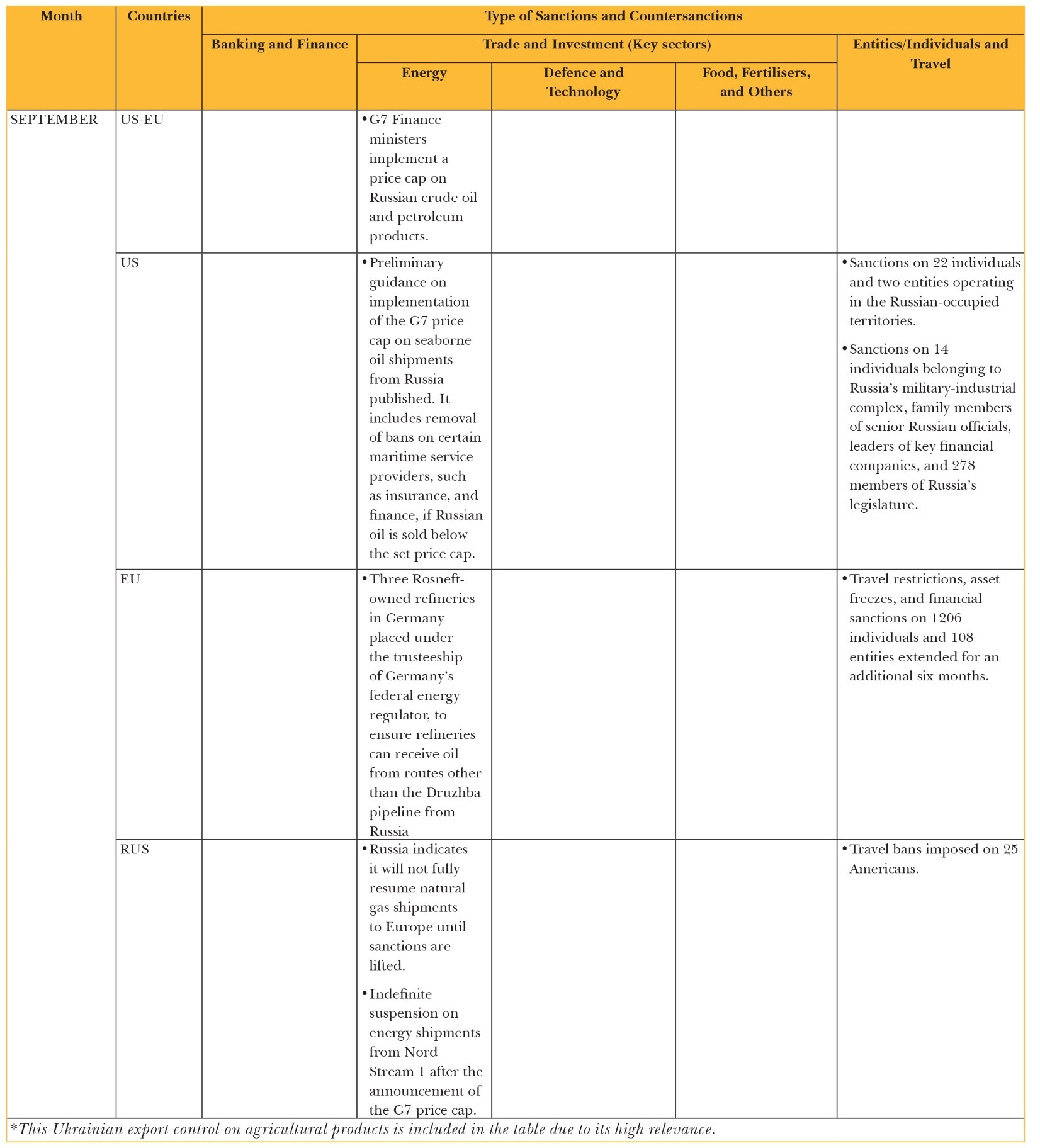

The sanctions against Russia were swift, severe, and coordinated; several countries announced additional sanctions at regular intervals following the start of the war. As the war raged on different fronts, Russia also announced measures to limit the impact of the western sanctions through some countersanctions (see Table 3).

Table 3: Overview of US and EU Sanctions, and Russian Countersanctions (February-September 2022)

It is difficult to accurately assess the impact of sanctions imposed on Russia in 2022 as they are linked to several other factors, including a protracted Russia-Ukraine war, military aid by the western countries to Ukraine, interaction of COVID-19-recovery policies and initiatives, and numerous global and regional challenges. Russia has maintained that the Western sanctions have had a limited overall impact on it, which contradicts the West’s assertion.

In April, the World Bank projected that Russian GDP would likely contact by 11.2 percent in 2022.[42] Some other economic forecasts in April-May indicated contraction between 8 percent and 10.4 percent.[43] The IMF’s World Economic Outlook released in October projected Russian GDP would contract by 3.4 percent in 2022, compared to a projection of minus 6 percent in July and minus 8.5 percent in April.[44] It also highlighted that the Russian crude and non-energy exports were seen holding better than expected. The Russian Ministry of Economic Development estimated that the country’s economy will shrink by 4.2 percent in 2022 , 2.7 percent in 2023, and grow by 3.7 percent in 2024.[45] The Russian ruble collapsed to its lowest levels in the weeks after the Ukraine invasion but became the world’s best performing currency by June 2022.[46] A US Congressional research paper released in May indicated that though Russian trade was severely impacted, its current account surplus for 2022 could still exceed US$250 billion, with windfall earnings from energy exports.[47] This is due to specific ‘carve-outs’ for energy exports—due to the European dependence on Russia—permitted under the sanctions.[48]

Despite a decline in volumes and value, the Russian export model has shown some resilience.[49] Russia was able to find alternative markets for its energy and commodities, offering to supply this at attractive prices to some countries, including China and India. Russia has, however, struggled due to a sharp drop in imports—which have averaged around 20 percent of its GDP over the last decade[50]—with challenges related to obtaining input materials, parts, and technologies. Sectors like defence, automobiles, and engineering goods have seen adverse impacts. The aviation sector has also faced challenges for repair and maintenance.[51] A Yale University study conducted in August concluded that Russian fiscal and monetary interventions to counter sanctions would not yield sustainable results, the economy was already suffering at the macro level, and that the country was looking at “economic oblivion” in the long-term if the sender countries stayed united.[52]

Overall, the impact on the Russian economy has been adverse, but not catastrophic, until September. In the medium-term, the impact is likely to be significant. On the other hand, Ukraine has been devastated by the war, with very high human, social, and economic costs. The Ukrainian GDP is expected to contract by 30 percent to 40 percent in 2022, more due to the war and to a lesser degree due to the impact of sanctions and countersanctions.

Unlike during the 2014-21 period, sanctions imposed in 2022 have had a significant impact on the sender and other countries. The US economy has been impacted mainly on account of high energy prices, high inflation, and rising interest rates. The impact on the EU economies has been more severe due to closer trade and financial ties with Russia. In May, the European Commission (EC) forecast a bleak picture for the EU and Euro area, though the vulnerability of each EU state was different, as indicated by the EC in the vulnerability index.[53] The EC also forecast lower growth and higher inflation and added that the balance of risks surrounding the assessment was skewed towards adverse outcomes. In May, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) indicated a profound impact and lowered the estimates for output in the EBRD area by 3.1 percent from the November 2021 estimates.[54] In May, Germany reported its first monthly trade deficit since 1991, and the UK reported its highest level of trade deficit since 1955.[55] Europe was already facing energy shortages and high prices before the war, and the sanctions significantly exacerbated these issues.[56] Gas prices were benchmarked to high-cost liquified natural gas (LNG) rather than low-cost pipeline gas. Despite diversification and a somewhat reduced dependence on Russia since 2014, the EU still imported 39.2 percent of gas, 24.8 percent of crude oil, and 46 percent of coal from that country in 2021.[57] During the first half of 2022, the US became the largest supplier of LNG to the EU and the UK.[58] As of 30 September 2022, the EU imported coal, oil and gas worth more than €100 billion from Russia, since the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. This was due to high prices, and despite reduction in the share of Russian energy in the EU’s imports. The ban on coal imports from August 2022 could not be implemented effectively. The EU’s estimated overall 11 percent drop in total gas consumption in the first half of 2022 was counterbalanced by an increase in the use of oil products by 8 percent, hard coal by 7 percent, and lignite by 12 percent.[59] The EU has been forced to implement power conservation, lower demand, financial support to control energy prices, diversify sources of supply, and rethink its entire energy transition plan. After substantial efforts to build consensus, the EU also announced a plan to cap the price of Russian oil imports, though the pricing formula for the same has not been made public, at the time of this writing.[60]

The sanctions on Russia came at a time when supply chains had already been tested by the COVID-19 pandemic and China’s zero-COVID policy. While countries around the world hoped for a post-COVID-19 economic recovery, the sanctions exacerbated the existing global economic challenges due to elevated inflation (in energy, food, fertilizers, and others), rise in input costs, combination of supply-side and demand-side shocks, tightening global financial conditions, slowdown in trade growth, and continued supply-chain disruptions. The primary reason for the high levels of inflation around the world is the sanctions against Russia.[61] The IMF lowered baseline global growth projections in April and July 2022 to 3.6 and 3.2 percent, respectively, highlighting that the downside risks were materialising.[62] In early October, the IMF chief highlighted that these projections will be downgraded further, and that the risks of recession are rising globally.[63] In April, the World Trade Organization announced that global trade growth may decline from 4.7 percent to between 2.4 percent and 3 percent in 2022.[64] Emerging market economies have also been adversely affected. Many developing economies have been facing acute debt stress (with defaults on debt repayment in some cases), dwindling foreign exchange reserves, and volatility in the currency markets. The poorer countries have been major losers, with the situation in some cases leading to violent protests and domestic turmoil.[65] The freezing of Russia’s foreign reserves was also seen as undermining financial markets worldwide, and it damaged trust in the international rules-based order that the West seeks to preserve.[66]

While Russia has managed to withstand the onslaught of unprecedented sanctions to some extent in the short-term, it is faced with many structural problems. The long-term consequences for the Russian economy can be significant, though the degree of severity will depend on several factors. The economic consequences for the sender countries—particularly the EU—have been higher than initially anticipated. Further, the scale and speed of sanctions have also led to unintended negative consequences for the global economy and the wider Global South. In some cases, the impact has been severe, leading to political and social unrest and hardship for countless people. Driven by their economic imperatives, many countries in Asia, Africa and Latin America have not supported the western sanctions.[67]

Diplomatic efforts for a ceasefire were initiated at the end of February when direct talks between Russia and Ukraine began in Belarus. But three rounds of talks failed to achieve any breakthrough. Russia’s demands included a change in the Ukrainian constitution to express its neutrality, formal recognition of Crimea as Russian territory and republics of Luhansk and Donetsk as independent territories, and cessation of military action from the Ukrainian side. Ukraine indicated some flexibility on the neutrality issue but sought restoration of Ukrainian sovereign control over the territories occupied by Russia. As key players influencing the talks, the US and the EU were keen that Ukraine does not yield to the pressure of the Russian military actions. The realisation of mistakes in the failed Minsk Agreements[70] made it harder to achieve a ceasefire acceptable to both sides. The West also considers that a potential ceasefire at or close to current control of territories would be perceived as victory for Russia. Subsequent talks in Turkey and meetings through videoconferencing in March also failed to break the deadlock.[71] The continued war and the consequent destruction was accompanied by newer sanctions, countersanctions, and increased military aid to Ukraine, which has gradually hardened the position on both sides. The accumulated costs have significantly narrowed the space for negotiations. No further direct talks have taken place since March, and the Western countries have not indicated the conditions under which sanctions will be lifted or rolled back. The war and sanctions have led to stronger unity and political cohesion in the EU, and between the EU and the US. The western allies have also pushed for a stronger and expanded NATO, increased military spending, and a hard military posture. The expansion of Europe’s military capabilities to improve deterrence against Russia has been set into motion.

Russia’s defence manufacturing, repair, and support activities have been adversely impacted by the sanctions, yet it has so far been able to sustain its war effort in Ukraine. However, its ability to expand the scope of military operations has been degraded. There has been no visible change in the Russian political outlook due to the sanctions, and the prospects of a negotiated settlement remain bleak. The agreement between Russia and Ukraine in July, brokered by the UN and Turkey, to allow the export of grains from Ukrainian ports in the Black Sea raised hopes that this could be a building block for a ceasefire. On the contrary, the military operations entered a phase of higher tempo after the shipments began. Russia also suffered some key tactical reverses in August and September, and was forced to announce a “partial mobilization” by recalling about 300,000 reservists.[72] After a hastily conducted referenda, Putin signed treaties in end September that included the accession of “Donetsk and Lugansk people’s republics and Zaporozhye and Kherson regions to Russia”.[73] In his speech, Putin proposed a revival of peace talks, with “Donbas off the Table”, which effectively ruled out any direct negotiations in the near-term. Russia appears to be aiming to hold and defend the ‘new border line’, and Ukraine appears more confident, with the support of aid and sanctions, to retaliate and attempt further push back. Russia will prefer a stalemate around the new territories, but the West is unlikely to accept any form of normalisation of the new annexation. As the war and the sanctions get more protracted, the alternatives available to Russia are likely to narrow.

In the first few months of the war, the sanctions did not go off as well as expected by the Western countries.[74] They also stiffened Russia’s political will to sustain its campaign, even with adverse impact on the means available for this. However, in the medium to long term, the sanctions may make a reasonable contribution to the West’s political objectives by weakening Russia. At the global level, the new model of war-aid-sanctions has generated anxiety and concern and exposed the limits of power projection through sanctions. The war and the sanctions have also initiated many geopolitical shifts and realignments, well beyond the conflict zone.

Conclusion

The use of economic sanctions as a policy instrument has increased in recent years, as seen during the Russia-Ukraine conflict since March 2014. Sanctions against Russia, led mainly by the US and the EU, are complemented by numerous other policy actions, and their overall impact is also influenced by other international, regional, and local factors.

To assess the economic and political impact of these sanctions and countersanctions, it is necessary to view it as two distinct phases: the first, from 2014 to 2021; and the second, from February 2022 onwards. In the first phase, the sanctions were gradually expanded in scope and intensity, with due care to avoid serious consequences on the sender countries. The sender countries targeted only a limited decoupling from Russia. The Russian economy was weakened during this period, though the impact was not very significant. Russia also took measures to reduce the impact and used this extended period to prepare itself for an anticipated broader set of sanctions in the future. At the political level, the sanctions did not influence Russia to change its objectives. The Minsk Agreements and subsequent negotiations failed to deliver any settlement, and a full-scale war was delayed but not prevented. These sanctions—as well as the threats of additional, massive, and coordinated sanctions—did not deter Russia from invading Ukraine in February 2022. The global impact of the sanctions during the 2014-21 period was also minimal, as an incremental approach with limited scope enabled the by international financial, trading, and geopolitical architecture to adapt to the situation.

The sanctions during the second phase (commencing February 2022) have been more comprehensive, coordinated, and sharp. Unlike the first phase, these sanctions have run in parallel with a full-scale war and extensive military aid to Ukraine. Russian economic and financial activity was severely disrupted in the initial months, but the country was able to achieve a fair degree of economic stability for the short-term through various policy measures that were significantly aided by high energy prices and strong export earnings. However, the Russian economy is being structurally impacted, with potential long-term consequences. Russia has been able to sustain its war effort and popular support for the same. However, strains in the availability and maintenance of platforms and equipment, logistics, personnel, support services, and inter-agency coordination have become evident. Sanctions have contributed to limiting Russia’s war strategy alternatives, though it remains committed to militarily defend the four Ukrainian regions that it has formally incorporated into sovereign Russian territory. The Ukrainian identity has been reinforced, and the process of expansion and strengthening of NATO has gained momentum: Sweden and Finland announced their intent to join the NATO after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and (as of July) have completed the accession talks and await their official integration into the alliance; and in end-September, Ukraine’s president announced that the country will officially apply for NATO membership. The sanctions have also contributed to hardening the stand on both sides, and severely limited the prospects of a negotiated settlement.

The sender countries, particularly the EU, have also faced major economic impacts from the sanctions in 2022, which was not fully anticipated. An economic recession looms large, and a major reorientation of political, economic, and security architecture is well underway. The sanctions and countersanctions have also led to a significant global impact and created serious economic difficulties for many developing countries.

As the conflicts prolongs, the sanctions are likely to hurt Russia significantly and will influence political outcomes. At the same time, the sender countries and the world at large will also continue to suffer serious consequences until some settlement or ceasefire is reached, and the process of winding down the sanctions begins.

The overall impact of sanctions and countersanctions continues to evolve, and their contribution to achieving economic and political objectives will need to be evaluated over a long time to derive suitable lessons. Nevertheless, the likelihood of increased and frequent usage of such an ‘economic weapon’ is certain to influence the emerging geopolitical and geoeconomics landscape.

Endnote

[a] An Association Agreement is a legally binding agreement between the European Union and a third country (or, as in this particular instance, a group of countries that joined the Eastern Partnership) that serve as a framework for cooperation between the associated parties.

[b] Named after Maidan Nezalezhnosti, or Independence Square, the central square in Kyiv.

[c] Agreements in 2014 and 2015 for a ceasefire and the restoration of normalcy between Russia and Ukraine. The final agreement later broke down due to a lack of trust and non-implementation by both sides.

[1] Nicholas Mulder, The Economic Weapon: The Rise of Sanctions as a Tool of Modern War (Yale University Press, 2022).

[2] “Sanctions” ,United Nations Security Council.

[3] Ghasem Zamani and Kazem Gharib Abadi, “Legitimacy and Legality of Unilateral Economic Sanctions Under International Law”, Judicial Law Views Volume 20. Issue 72, (2016).

[4] Global Sanctions Database, “Global Sanctions Database – GSDB”.

[5] Daniel W. Drenzer, “Serious About Sanctions”, The National Interest, no. 53 (1998): 66-74.

[6] Robert A. Pape, “Why Economic Sanctions Do Not Work”, International Security, Volume 22, No. 2 (1997): 90-136.

[7] David A. Baldwin, Economic Statecraft (Princeton University Press, 2020).

[8] Maarten Smeets, “Can Economic Sanctions Be Effective?”, World Trade Organisation, Staff Working Paper, ERSD-2018-03.

[9] Jeffrey Mankoff, Russia’s War in Ukraine: Identity, History, and Conflict, Centre for Strategic and International Studies, 2022.

[10] Susanne Oxenstierna and Per Olsson, The Economic Sanctions against Russia: Impact and Prospects of Success, Swedish Defence Research agency, FOI-R-4097, 2015.

[11] United Nations, “General Assembly Adopts Resolution Calling upon States Not to Recognize Changes in Status of Crimea Region- UN Press,” March 27, 2014.

[12] Ivan Gutterman and Wojtek Grojec, “A Timeline of All Russia-Related Sanctions,” Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty, 2014.

[13]Marcus Lu, “A Recent History of US Sanctions on Russia”, Marcus Lu, Visual Capitalist, 2022.

[14] US International Trade Administration, “Russia-Country Commercial Guide- Sanctions”.

[15] Vladimir Soldatkin and Oksana Kobzeva, “Expanded U.S. Sanctions May Affect Russia’s Foreign Expansion in Oil and Gas,” Reuters, November 1, 2017, sec. Integrated Oil & Gas.

[16] OECD, “Statement by the OECD Regarding the Status of the Accession Process with Russia & Co-Operation with Ukraine – OECD,” www.oecd.org, March 13, 2014.

[17] European Council, “Timeline-EU Restrictive Measures Against Russia Over Ukraine”, Council of European Union.

[18] Ikka Korhonnen, “Economic Sanctions on Russia and their Effects”, NYU Jordan Centre for the Advanced Study of Russia, October 28, 2021.

[19] International Monetary Fund, Russian Federation- Article IV Staff Report, Washington DC, IMF 2019.

[20] World Bank Group, “GDP (Current US$) – Russian Federation | Data”.

[21] Bank of Russia, “International Reserves of the Russian Federation (End of Period) | Bank of Russia”.

[22] World Integrated Trade Solution, “Russian Federation Product Exports and Imports 2019- WITS Data,” Worldbank.org, 2019.

[23] Anders Aslund, “Western economic Sanctions on Russia Over Ukraine 2014-2019”, CESifo Forum, Volume 20 (2019).

[24] Anders Aslund and Maria Snegovaya, The Impact of Western Sanctions on Russia and How They Can Be Made Even More Effective, Atlantic Council Report, 03 May 2021.

[25] Richard Connolly, “Western Economic Sanctions and Russia’s Place in the Global Economy”, E-International Relations, (2015).

[26] “Ukraine Ceasefire: New Minsk Agreement Key Points”, BBC News, February 12, 2015.

[27] Adam DuBard, “2014 and Now: Will Sanctions Change Putin’s Calculations”, Friedrich Naumann Foundation, March 03, 2022.

[28] NATO, “Boosting NATO’s Presence in the East and Southeast,” NATO, 2019.

[29] The Economist, “How Western Governments Are Getting Military Gear into Ukraine,” The Economist, March 2, 2022.

[30] Boosting NATO’s Presence in the East and Southeast, 2019.

[31] Centre for Preventive Action, “Global Conflict Tracker – Conflict in Ukraine”, Council on Foreign Relations.

[32] Peter van Bergeijik, “Economic Sanctions and the Russian war on Ukraine: A Critical Comparative Appraisal”, International Institute of Social Studies, Erasmus University, Rotterdam, March 2022.

[33] Lara Geiger, “2014 Sanctions Against Russia Failed, Is the Second time the Charm?” Columbia Political Review, April 07, 2022.

[34] Joint Statement on the U.S.-Ukraine Strategic Partnership, The White House, September 01, 2021.

[35] Background Press Call by Senior Administration Officials on Russia Ukraine Economic Deterrence Measures, The White House, January 25 2022.

[36] President von der Leyen, Munich Security Conference February 19, 2022, European Commission.

[37] “Full Text of Vladimir Putin’s Speech Announcing ‘Special Military Operations’ in Ukraine”, The Print, February 24, 2022.

[38] Peterson Institute for International Economics, “Russia’s War on Ukraine: A Sanctions Timeline | PIIE,” www.piie.com, March 14, 2022.

[39] Girish Luthra, “The Russia- Ukraine War, Economic Sanctions, and Global Headwinds”, ORF, July 22, 2022.

[40] Alexander Osipovich, “Russia Turns On Spending Taps to Blunt Economic Impact of War and sanctions”, The Wall Street Journal, May 02, 2022.

[41] Zhengjun Zhang and Yanyan Li, “Why US Sanctions on ‘State Controlled’ Chinese Companies Smack of Hypocrisy”, South China Morning Post, May 05, 2022.

[42] Office of the Chief Economist, War in the Region-Europe and Central Asia Economic Update, Spring 2022, World Bank Group.

[43] De Lemos Peixoto Samuel et al., “Economic Repercussions of Russia’s War on Ukraine-Weekly Digest”, European Parliament, May 17, 2022.

[44] World Economic Outlook Update: Gloomy and More Uncertain, International Monetary Fund, July 2022.

[45] Evgeny Gontmakher, Appraising Russia’s Wartime Economy, GIS Report Online, September 12, 2022.

[46] Jason Karain, “The Russian Ruble Keeps Rising, Hitting a Seven Year High”, New York Times, June 22, 2022.

[47] Rebecca M. Nelson, Russia’s War on Ukraine: The Economic impact of Sanctions, Congressional Research Service, May 03, 2022.

[48] Robin Wright, “Why Sanctions Too Often Fail”, The New Yorker, March 07, 2022.

[49] Anna Pestova, Mikhail Mamonov, and Steven Onggena, “The Price of War: Macroeconomic Effects of the 2022 Sanctions on Russia”, VOXEU Column, CEPR, April 15,2022.

[50] World Bank, “Imports of Goods and Services (% of GDP) – Russian Federation- Data”.

[51] Tanmay Kadam, “Russia’s Staggering Move Battered by Sanctions, Moscow Turns to Iran for Help on Aircraft Repair and Maintenance”, Eurasian Times, May 02, 2022.

[52] Jeffrey A Sonnenfeld et al., “Business Retreats and Sanctions Are Crippling the Russian Economy”, Yale University, (2022).

[53] European Commission, Spring 2022 Economic Forecast: Russian Invasion Tests EU Economic Resilience, European Commission, May 2022.

[54] Marcus Warren, War in Ukraine and Inflation Slow growth in EBRD Regions, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, May 10 2022.

[55] Sandipan Deb, “Ukraine Crisis: A War That Is Hurting the West More Than Russia”, First Post, July 07, 2022.

[56] Brenda Shaffer, “With Winter Coming, Europe is Walking Off a Cliff”, Foreign Policy, September 29, 2022.

[57] Ankita Dutta, “Assessing Europe’s Spiraling Energy Crisis”, ORF, September 28, 2022.

[58] The Maritime Executive, “U.S. Becomes Largest LNG Exporter in 2022 Driven by European Demand,” The Maritime Executive, July 26, 2022.

[59] Chris Campbell, “Climate Graphic of the Week: EU Payments for Russian Fuel since War Reach beyond €100bn,” Financial Times, October 8, 2022.

[60] “EU Likely to Cap Russian Oil Over Ukraine War, Annexation of 4 Regions”, Mint, October 05, 2022.

[61] TK Arun, “Ukraine War: A Tradeoff Between western Losses and Developing World Misery”, Moneycontrol, July 25, 2022.

[62] “World Economic Outlook Update: Gloomy and More Uncertain, July 2022”.

[63] The Times of India, “World Bank, IMF See Rising Risks of Global Recession – Times of India,” The Times of India, October 07, 2022.

[64] Colm Qinn, “Russia’s War Leaves Ukrainian Economy in Ruins”, Foreign Policy, April 12, 2022.

[65] Brahma Chellaney, “Why Sanctions Against Russia May Not Work”, The Hill, May 02, 2022.

[66] Arvind Subramanian and Josh Fulman, “The West Has Got Its Russia Sanctions Wrong”, Business Standard, May 12, 2022.

[67] Sarah Westwood, “Which Countries Have Decided Not to Sanction Russia?,” Washington Examiner, March 03, 2022.

[68] Alice Speri, “U.S. Military Aid to Ukraine Grows to Historic Proportions — along with Risks,” The Intercept, September 10, 2022.

[69] Alan Crawford et al., “The US Led Drive to Isolate Russia and China is Falling Short”, Bloomberg, August 08, 2022.

[70] Hugo von Essen and Andreas Umland, “The Road to a Ceasefire in Ukraine is Full of Pitfalls”, Foreign Policy, July 07, 2022.

[71] “Ukraine and Russia hold third round of talks”, DW, March 07, 2022.

[72] Paul Sonne et al., “Rapid loss of territory in Ukraine reveals spent Russian military”, The Washington Post, September 13, 2022,

[73] “Signing of Treaties on Accession of Donetsk and Lugansk People’s Republics and Zaporozhye and Kherson regions to Russia”, The Kremlin, Moscow, September 30, 2022.

[74] “Are Sanctions Working? The Lessons From a New Era of Economic Warfare”, The Economist, August 25, 2022.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Vice Admiral Girish Luthra is Distinguished Fellow at Observer Research Foundation, Mumbai. He is Former Commander-in-Chief of Western Naval Command, and Southern Naval Command, Indian ...

Read More +