-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

PDF Download

PDF Download

Mohammed Sinan Siyech, “The Return of the Taliban: ‘Foreign Fighters’ and Other Threats to India’s Security,” ORF Issue Brief No. 515, January 2022, Observer Research Foundation.

Introduction

In the several months since the return to power of the Taliban in Afghanistan, the world’s attention may have already shifted to other global developments including the challenges being posed by the long COVID-19 pandemic. Yet, for India, the events in Afghanistan continue to demand great attention. This brief examines the implications of Indian citizens leaving the country to join the ranks of “foreign fighters” in Afghanistan, given the safe haven that Taliban rule provides to many terrorist groups. Drawing on primary and secondary sources, the brief calls on India to be watchful of the first- and second-order effects of this phenomenon.

The following section provides an overview of the current situation in Afghanistan. The brief then discusses the various implications of Taliban rule for India, setting the background for the next section which evaluates the threats posed by the phenomenon of “foreign fighters”. It studies the cases of previous conflicts that attracted foreign fighters in large numbers, in order to explore the security threats facing India. The brief closes with certain policy recommendations for the Indian government to engage with this threat in the long term.

Afghanistan’s Conflict Landscape

Having taken control of the government in Afghanistan following the withdrawal of US forces, the Taliban is seeking to transition from an insurgent group to a governing body, and therefore must contend with the challenges of governance, including opposition to its rule.[1] While it has now managed to co-opt many different actors into its fold, it is also constantly being challenged by the Islamic State (IS) with which it has had a long-running bloody feud since 2014 when the latter established its Khorasan province in Afghanistan.[2] Since 2014, the Taliban has scored numerous victories against the IS, some of them facilitated by US drone attacks on senior IS leadership.[3]

The Islamic State has opposed the Taliban on ideological grounds; IS calls the group “Taliban 2.0” and accuses it of “compromising” on various issues. According to a 22-page document titled, “The Deviances of the Taliban 2.0”, released by IS supporters in their Telegram Channel Al Anfaal, the Taliban has been guilty of “not commanding the good and forbidding the evil.”[4] It listed more than 15 different issues it had with the Taliban. Indeed, the IS attacked the group consistently in 2021 for engaging with international powers such as the US and its Western allies, and going soft on groups like the Shias and Ahmadis.[5] Such animosity has not been confined to issuances and verbal offensives; Shia mosques have been attacked in various incidents, resulting in the deaths of 400 people between August and October 2021 alone.[6]

With the Taliban turning itself into a governing body, its rivalry with the IS has entered a new phase. While the US has offered counterterrorism assistance to the Taliban, the latter turned it down, citing a lack of credibility.[7] This also reflects its aim to not be seen as an ally of the same powers it fought for two decades.

At the same time, various other terrorist groups—especially those based in Pakistan—have also begun to take refuge in Afghanistan. For instance, a United Nations monitoring team has reported that the Lashkar e-Taiba and the Jaish e-Mohammed, both of them lethal and responsible for various attacks on India, have been fighting alongside the Taliban against the previous government in Kunar, Nangarhar, and Nuristan.[8] This is a consequence of their past relations with the group, when they first engaged with fighting off the Soviets in the 1980s. Moreover, groups aligned with the ISKP, such as the anti-Shia Lashkar e-Jhangvi, have also become more active. Collectively, all of these groups present significant security implications for India.

Implications of Transnational Terrorism on India

The conflict landscape of Afghanistan is diverse and multi-faceted, characterised by rivalries between jihadist groups and competition for recruits. The impacts go beyond the borders of Afghanistan.

First, a Taliban-controlled Afghanistan poses the threat of exacerbating the volatile situation in Kashmir. Kashmir has witnessed terrorist attacks on minority community members, and has a long history of insurgency with roots in Afghanistan in the late 1980s. It was during the USSR-Afghanistan Mujahideen conflict that this insurgency began; at that time, fighters from Afghanistan, along with the Pakistani army, had trained Kashmiri insurgents.[9] When the Taliban took control in the early 1990s, they provided safe havens to Kashmiris who needed to recompose before returning to the insurgents’ ranks. A redux of the Taliban controlling territory and providing shelter to terrorist groups could cause a flare-up of tensions in Kashmir.

A second concern for India is the presence of anti-India groups based in Pakistan that could gain legitimacy from the Taliban’s strength, and train their focus on India. Pakistani groups such as Lashkar e-Taiba and Jaish e-Mohammed have long been involved in conducting operations in India, including an attack on the Indian Parliament in December 2001, and the 2016 attacks on the Pathankot airbase and Uri military bases that led to military retaliation from India. Part of the strategy of these groups is to disseminate propaganda against India over different platforms; India will be keeping a keen eye on these groups.

According to a July 2021 media report, Taliban fighters, over the years, had been directed by the Pakistani InterServices Intelligence agency (ISI) to attack Indian infrastructure in Afghanistan.[10] Other, more worrying reports, have highlighted that thousands of fighters from Pakistani groups that are active in Kashmir, such as the LeT and JeM, have fought alongside the Taliban. Such presence of LeT and JeM with the Taliban was also linked to New Delhi’s decision to evacuate its consulate in Kandahar, where its personnel were airlifted via Zahedan, Iran, back to India, in August 2021.[11]

A third concern for India is the presence of transnational terrorist groups such as the Islamic State in the Khorasan Province (ISKP), and the Al-Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent. For instance, Al-Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent has already hailed the US withdrawal from Afghanistan as a victory. In early 2021, they changed the name of their magazine from Nawai Afghan Jihad (Voice of the Afghan Jihad) to Nawai Ghazwat ul Hind (Voice of the Conquest of India), spelling out where their energies could be focused after the US’s complete withdrawal.[12] Moreover, it is already clear that the Taliban has not gone beyond paying lip-service to ousting the Al-Qaeda, and there is concern that the latter will only grow in strength in the coming days.[13]

In October 2021, the group released two videos through their media channels and on platforms like Telegram calling for armed conflict in India, especially in Kashmir. This shows that the safe haven provided to the group’s leadership in Afghanistan is likely already giving dividends to the group which can now focus on India, apart from other nations.[14] This narrative is not uniformly accepted, however; Indian security agencies have attributed these videos to Pakistani intelligence.[15]

Similarly, the ISKP which, as discussed earlier, has recently conducted attacks in Afghanistan, has also been a cause of concern for India.[16] In 2017 and 2018, individuals from Kerala travelled to Afghanistan and joined the Islamic State in search of a “pure Islamic atmosphere.”[17] Since then, India has grappled with the policy implications of the deaths of these fighters.[18] Given how Afghanistan has created a safe space for jihadists across South Asia, there is also fear that individuals interested in joining either the Islamic State or other jihadist groups will move to Afghanistan.

The ‘Foreign Fighters’ Phenomenon

The term “foreign fighters” is used in this brief to refer to those individuals who join conflicts abroad. Hegghammer notes that a few factors characterise foreign fighters in that they are agents who 1) have joined, and operate within the confines of, an insurgency; (2) lack citizenship of the conflict state or kinship links to its warring factions; (3) lack affiliation to an official military organisation; and (4) are unpaid.[19] In more recent times, “foreign fighters” have become synonymous with “foreign terrorist fighters” following definitions by organisations such as the United Nations.[20] While most foreign fighters make their way to the ranks of jihadist groups such as in Syria and Iraq, there are those who have joined other conflicts: the Spanish Civil war of 1936 – 1939,[21] for example, and the ongoing Ukraine conflict where an estimated 17,000 fighters from different parts of the world have joined.[22]

Academic literature discusses various aspects of the phenomenon of foreign fighters, including why certain conflicts attract them,[23] what their motivations and impacts are,[24],[25] and why foreign fighters choose to stay.[26] Pertinent to this brief is the discussion on the impact of foreign fighters to the security of their country of origin. Today, for India, security agencies have to contend with the probability of individuals leaving the country to join terrorist groups in Afghanistan after the ascendance of the Taliban to power. It is a risk that cannot be taken lightly given the history of conflicts in South Asia, and the role of foreign fighters.

The biggest conflict that drew foreign fighters to its fold was the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in the 1980s that led to an insurgency which in turn birthed the Taliban and attracted close to 30,000 different people of various nationalities.[27] South Asians comprised a large number of those fighters. Bangladeshi scholar Ali Riaz has noted that the country’s recruits to Afghanistan numbered in the low thousands, comprising a significant proportion of the total fighters.[28] Pakistanis who were spurred by the ISI also joined the conflict in droves.[29]

The impact of these foreign fighters has been unmistakeable. Those who travel to another country to participate in their conflict for ideological reasons are imbibed with more violent versions of their own ideology, trained in firearms and military tactics, and gain considerable networks from which to exchange information and raise finances for the future.[30]

Accordingly, foreign fighters who stay all the way till the end of a conflict often have varied trajectories after the conflict. There are six pathways for foreign fighters after a conflict:[31] re-integrating into normal life without again taking up arms; becoming government assets for security agencies, such as what happened in Yemen; going back to their countries, forming groups, and working to spark revolutions as in the cases of Algeria and Egypt; facilitating the movement of other aspiring fighters to different conflict zones; continuing to take part in other conflicts such as in Serbia and Kosovo—these individuals are referred to as “career foreign fighters”;[32] and conducting attacks in the name of Islam without being anchored to any group.

For India, the latter four categories are of security consequence either directly or indirectly. Those who went back to their country after the Afghan conflict of the 1980s included people who later formed the Jamaat ul Mujahideen in Bangladesh and the LeT and JeM, among others. The senior members of these organisations were all trained in Afghanistan and all these groups have conducted attacks in India at some point or the other. This category of individuals also overlapped with the facilitators who tried to send many members of the LeT and others to launch attacks in Indian territory.[33] The “career foreign fighters” have also taken part in the insurgency in India, training local Kashmiris or themselves engaging in insurgency and becoming the progenitors of the Kashmiri insurgency that began in 1988 and ‘89.[34]

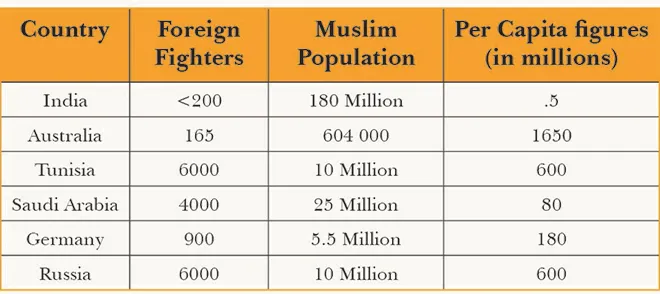

For India, not many of its own citizens took part in the first Afghan conflict.[35] The reasons for this are diverse: the overt lack of opposition to the Soviet invasion, thereby not allowing for media narratives that supported the rebels in Afghanistan; domestic strife for Muslims; and India’s foresight in understanding that rebels going to fight in Afghanistan would also fight in Kashmir.[36] Even later on, after the rise of IS in Iraq and Syria, the number of foreign fighters remained low in both absolute and relative terms (see table 1).[37]

Here too, other factors exist: government interception using cyber tools; family resistance; opposition by religious clerics of all denominations within India; and bureaucratic and economic challenges. Foreign fighting thus became an activity of the economically better-off Indian Muslims.[38]

Table 1. Total and Per-capita Numbers of Muslims Who Joined the Islamic State

Current Risks

All this is not to say, however, that there is no current risk of Indians having intentions of travelling to Afghanistan again to take part in the conflict there. The main foreign fighters contingent of 21 people to have joined the Islamic State from India went to Afghanistan in 2017,[40] and not Iraq or Syria, demonstrating the role of geographic proximity in their decision-making. Some of them had an active role in attacks on different targets;[41] many have died since, leaving behind widows who have not expressed remorse in joining the group despite wanting to come back to India.[42]

Given that the motivations of these people were to live in what they believe as a “pure Islamic atmosphere”— and not to fight alongside the Islamic State—there are chances that more individuals could find the same reason to leave India and migrate there. In Islamic terms, this concept is known as hijra (migration)—part of what Muslim scholars underline to be essential obligations of those who practice Islam: to travel to countries where their brethren can practise the religion without interference.[43] This is part of an ongoing global conversation among Muslims, and it is plausible that a minuscule section of Indians who feel the need to travel abroad may repeat what the Kerala cohorts did a few years ago.

This also creates the risk of people who may be going to Afghanistan without any intention to join the ranks of the Taliban, but who could eventually do so after succumbing to the vagaries of living in a conflict zone. The process could create security threats for India.

A more immediate threat is that of foreign fighters moving the other way—from other countries, down to India, to join the insurgency in Kashmir. In August 2021, more than 30 militants in Kashmir were reportedly found to be foreigners—this highlights the role that foreigners continue to play in the Kashmiri conflict.[44]

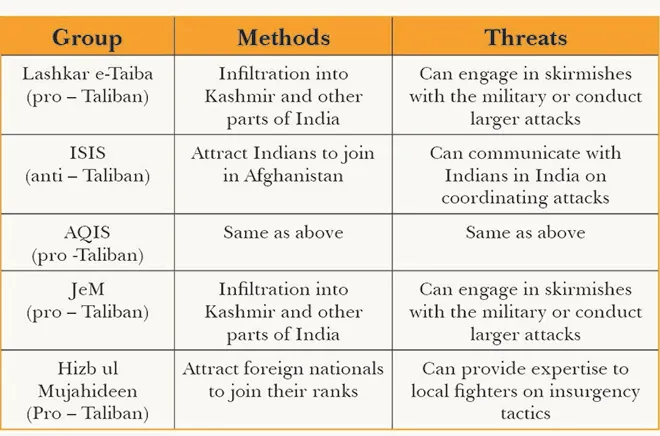

Indeed, the threats to India in the post-Taliban landscape are manifold. India has to watch out for those who could travel to Afghanistan and join various groups there, including the Islamic State and Taliban, as well as allied groups such as Al-Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent. This class of foreign fighters could remotely direct individuals or cells in India to conduct attacks, funnel more people to Afghanistan, or travel back with enhanced military skills and cause security threats in different part of the country.

India would also need to deal with foreign fighters from Afghanistan entering India through Pakistan and aiming to further stoke the Kashmiri insurgency. It is also possible that Kashmiri insurgents could try to receive further training from these foreign fighters in Pakistan or Afghanistan. And finally, foreign fighters trained in Afghanistan and entering from Pakistan are also likely to conduct attacks in other parts of India. Taken individually, each of these may not pose a particularly big threat; together, they become a significant part of the national security challenge.

It would do India well to keep in mind that countries like Pakistan that have historically facilitated attacks in India are important factors in either stemming or easing the flow of foreign fighters due to its border status with India.

Table 2. Risks Posed by Foreign Fighters to India Following Taliban Victory

The Fundamentals of State Response

Policy responses to a potential movement of foreign fighters to Afghanistan must be planned at several levels. At the cyber level, Indian agencies can gauge the interest and willingness of Indians to travel to Afghanistan by aggressively monitoring social-media channels and apps. This strategy had worked for the Indian government in the aftermath of the declaration of the caliphate in 2014: they were able to identify close to 3,000 aspiring foreign fighters and dissuade them from travelling to join the Islamic State.[45] While the IS in its current form is no longer capable of dispersing as much propaganda as it did in 2014,[46] it still attracts recruits via these avenues. This was evident with the publication of the Sawt al Hind (Voice of India),[a] demonstrating how the IS was trying to attract people from South Asian countries, specifically Indians, to its fold.[47]

Second, Indian authorities should ensure that they engage with other stakeholder countries, including those in South Asia and the Gulf, which are often used as transit points to travel to conflict zones. Cooperation with Iran should also be encouraged; after all, there have been cases of people using the pretext of going on a pilgrimage to Iran to travel to Afghanistan and join the ranks of fighters there.[48] India could take a leaf out of the European Union’s (EU) playbook – especially for better cooperation with South Asia. The EU, which has always been far more well-connected and cooperative than nations in South Asia, have set up effective measures to prevent the exodus of foreign fighters. These include information-sharing, strict border controls, and checks for suspicious patterns of travel.[49]

Third, it would make a great difference to engage with the Muslim community in various states, including both religious figures and family circles. Both of these segments have been crucial in preventing individuals from travelling to join conflicts overseas, not just to India but also other countries.[50] For example, Singapore’s Islamic Council, Majlis Ugama Islamia Singapora (MUIS) has been proactive in disseminating narratives to counter terrorist propaganda from groups like the IS and have been able to arrest the phenomenon of their people joining terrorist groups abroad.[51]

Fourth, countries like Singapore employ strategies for integrating its minority populations into a larger, more inclusive national identity. This helps potential foreign fighters to reconsider their stance of travelling abroad to join a group for the sake of identity[52] – an otherwise common reason for joining a foreign conflict. While such measures may not be as easy in India given the more polarised atmosphere,[53] it should be strongly considered in counterterrorism policymaking.

India should also develop thought-out legal policies for those who do manage to travel and are deported before or after fighting alongside the terrorist groups. These measures must consider intentions, degree of participation in foreign conflict, level of ideological conviction to engage in violence, and remedial measures that can be taken to rehabilitate such individuals. Countries like Saudi Arabia and Indonesia, for example, have adopted various rehabilitation measures that include engaging with convicts from religious, familial, social, financial, and even artistic perspectives.[54] To be sure, it is not easy to bring all of this into deradicalisation programmes. Cities like Mumbai have met with a certain degree of success in their deradicalisation programmes.

Furthermore, to mitigate the impact of foreign fighters on the insurgency in Kashmir, the Indian government will also need to develop separate policies for the region. Even as military measures are undoubtedly part of this equation, it would be prudent to engage with the various economic and social issues that influence the conflict landscape. These include boosting tourism, nurturing social cohesion, and bolstering the safety of minority groups such as the Kashmiri pandits. These measures can help eliminate the public’s sense of kindredness with foreign terrorist fighters coming from Pakistan or other regions.

Conclusion

The current transnational nature of conflicts has given birth to the phenomenon of foreign fighters. Afghanistan is one conflict region that has attracted individual fighters from other countries. With the rise of the Taliban in Afghanistan and the resultant growth of other terrorist groups in the country, India faces threats to its security.

As this brief has outlined, the problems in Afghanistan have several implications that could spill over into Kashmir and other parts of India. Although the country has not yet witnessed a massive exodus of its citizens becoming foreign fighters, it is wholly possible that this could change. The threat emanates not only from pro-Taliban groups but also its opponents like the Islamic State.

Scrutiny should be heightened until the shock of the Taliban victory subsides and Afghanistan becomes less of an interest point for jihadist groups. Various lessons need to be picked up from India’s own counterterrorism practices as well as international experiences, as discussed in the earlier sections of this brief. This would be paramount if India aims to prevent the first- and second-order effects of foreign fighters coming from Afghanistan.

Endnotes

[a] The publication has since been stopped.

[1] Shahmahmood Mihkael, “For the Taliban, Governing Will Be the Hard Part”, United States Institute of Peace, October 2021, https://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/Afghan-Issues-Paper_For-Taliban-Governing-Will-Be-Hard-Part.pdf

[2] Amira Jadoon and Andrew Mines, “The Taliban Can’t Take On The Islamic State Alone”, War on the Rocks, October 14, 2021, https://warontherocks.com/2021/10/the-taliban-cant-take-on-the-islamic-state-alone/

[3] Jadoon and Mines, The Taliban Can’t Take On The Islamic State Alone

[4] Suraj Ganesan, “The Islamic State’s (IS) Critique of the US-Taliban Deal: A Case Study of IS’ Telegram Channels”, Counter Terrorist Trends and Analysis, Vol 13, No.4 September 2021 (21 – 25).

[5] Ganesan, “The Islamic State’s (IS) Critique of the US-Taliban Deal

[6] “Afghanistan: Surge in Islamic State Attacks on Shia”, Human Rights Watch, October 25, 2021, https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/10/25/afghanistan-surge-islamic-state-attacks-shia

[7] Bhavya Sukheja, “Taliban Rejects US Help To Fight ISIS; Snubs Offer To Jointly Combat Terrorism In Afghan”, Republic World, October 10, 2021, https://www.republicworld.com/world-news/rest-of-the-world-news/taliban-rejects-us-help-to-fight-isis-snubs-offer-to-jointly-combat-terrorism-in-afghan.html

[8] Dipanjan Roy Chowdhury, “Thousands of Pakistan nationals from LeT & JeM fighting alongside Taliban in Afghanistan: UN”, Times of India, June 04, 2020, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/defence/thousands-of-pak-nationals-from-let-jem-fighting-alongside-taliban-in-afghanistan-un/articleshow/76189061.cms?from=mdr

[9] Jonah Blank, “Let’s Talk About Kashmir”, Foreign Policy, September 05, 2014, https://foreignpolicy.com/2014/09/05/lets-talk-about-kashmir/

[10] Rakesh Singh, “ISI asks Taliban to target infra developed by India”, Daily Pioneer, July 19, 2021, https://www.dailypioneer.com/2021/page1/isi-asks-taliban-to-target-infra-developed-by-india.html

[11] Dipanjan Roy Chowdhury, “Thousands of Pakistan nationals from LeT & JeM fighting alongside Taliban in Afghanistan: UN”, Times of India, January 04, 2020, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/defence/thousands-of-pak-nationals-from-let-jem-fighting-alongside-taliban-in-afghanistan-un/articleshow/76189061.cms?from=mdr

[12] Rezaul h Laskar and Adil Mir, “Al-Qaeda’s India affiliate hints at shifting focus to Kashmir”, Hindustan Times, March 22, 2020, https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/al-qaeda-s-india-affiliate-hints-at-shifting-focus-to-kashmir/story-QgsOfxqfqe17uwYfs13pIJ.html

[13] Barbara Elias, “Why the Taliban Won’t Quit al Qaeda”, Foreign Policy, September 21, 2021, https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/09/21/taliban-al-qaeda-afghanistan-ties-terrorism/

[14] Kabir Taneja, “AQIS New Video”, Twitter, October 12, 2021, https://twitter.com/KabirTaneja/status/1447780205540511744

[15] Manoj Gupta, “Pak-based Terrorists Release ‘Fake’ Al-Qaeda Video to ‘Create Panic’ in India, Sources Say FATF Watching Closely. News 18, October 12, 2021, https://www.news18.com/news/india/twice-in-a-week-al-qaeda-in-indian-subcontinent-releases-new-video-named-kashmir-is-ours-4313042.html

[16] Samya Kullab, “Can the Taliban Suppress the Potent Islamic State Threat?”, The Diplomat, October 12, 2021, https://thediplomat.com/2021/10/can-the-taliban-suppress-the-potent-islamic-state-threat/

[17]Kabir Taneja and Mohammed Sinan, “The Islamic State in India’s Kerala: A primer”, ORF Occasional Report, October 15, 2019, https://www.orfonline.org/research/the-islamic-state-in-indias-kerala-a-primer-56634/

[18] K.S. Sudhi, “Freedom may remain a distant dream for IS widows”, The Hindu, August 19, 2021, https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/kerala/freedom-may-remain-a-distant-dream-for-is-widows/article35994442.ece

[19] Thomas Hegghammer, ‘The Rise of Muslim Foreign Fighters: Islam and the Globalization of Jihad’, in

International Security, Vol. 35, no. 3 (Winter 2010), pp. 55–91

[20] “Foreign Terrorist Fighters”, UNODC, January 2021, https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/terrorism/expertise/foreign-terrorist-fighters.html

[21] Samuel Kruizinga, “Fear and Loathing in Spain. Dutch Foreign Fighters in the Spanish Civil War”, European Review of History, Volume 27, No. 1-2, September 2020: 134 – 150

[22]Kruizinga, Fear and Loathing in Spain.

[23] Isabelle Duyvesteyn and Bram Peeters, ‘Fickle Foreign Fighters? A Cross-Case Analysis of Seven Muslim Foreign Fighter Mobilisations (1980–2015)’, ICCT Research Paper (The Hague: International Center for Countering Terrorism, 2015).

[24] Tiffany S. Chu and Alex Braithwaite, “The impact of foreign fighters on civil conflict outcomes”, Research and Politics, July – September 2017: 1-7

[25] Raphael Luduc, “The ontological threat of foreign fighters”, European Journal of International Law, Vol 27, No.1, 1-12

[26] Thomas Hegghammer, “Should I Stay or Should I Go? Explaining Variation in Western Jihadists’ Choice between Domestic and Foreign Fighting” American Political Science Review, Volume 107 No.1, 1-15.

[27] Ahmed Rashid, Taliban: The Story of the Afghan Warlords (London: Pan Books, 2001), p. 130; see also Daniel

Byman, ‘How States Exploit Jihadist Foreign Fighters’, in Studies in Conflict and Terrorism, Vol. 42, no. 12 (Aug.

2017), pp. 1–30

[28] Ahmed Rashid, Taliban: The Story of the Afghan Warlords (London: Pan Books, 2001), p100 – 150

[29] Rashid, The Story of the Afghan Warlords

[30] Rashid, The Story of the Afghan Warlords

[31] Mohammed M. Hafez, ‘Jihad after Iraq: Lessons from the Arab Afghans’, in Studies in Conflict and Terrorism, Vol.32, no. 2 (Jan. 2009), pp. 73–98

[32] Chelsea Daymon Jeanine de Roy van Zuijdewijn David Malet, “Career Foreign Fighters: Expertise Transmission Across Insurgencies”, Resolve Research Report, April 2020, https://www.resolvenet.org/system/files/2020-04/RSVE_CareerForeignFighters_April2020%20%281%29.pdf

[33] Stephen Tankel, Storming the World Stage: The Story of Lashkar-e-Taiba (Oxford: Oxford

University Press, 2011);

[34] Tankel, Storming the World Stage.

[35] Brian Glyn Williams, “On the Trail of the ‘Lions of Islam’: Foreign Fighters in Afghanistan and Pakistan, 1980-2010”, Foreign Policy Research Institute, 2011.

[36] Mohammed Sinan Siyech, “India’s Foreign Fighter Puzzle”, South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies, Vol 44, No. 1, February 2021. 1- 18.

[37] Kabir Taneja, “An Examination of India’s Policy Response to Foreign Fighters”, ORF Report, September 30, 2021, https://www.orfonline.org/research/an-examination-of-indias-policy-response-to-foreign-fighters/

[38] Siyech: India’s foreign fighter puzzle

[39] Richard Barrett, “Beyond the Caliphate ”Foreign Fighters and the Threat of Returnees”, Soufan Center, October 2017, https://thesoufancenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Beyond-the-Caliphate-Foreign-Fighters-and-the-Threat-of-Returnees-TSC-Report-October-2017-v3.pdf

[40] Kabir Taneja and Mohammed Sinan Siyech, “The Islamic State in India’s Kerala: A primer”, ORF Occasional Report, October 15, 2019, https://www.orfonline.org/research/the-islamic-state-in-indias-kerala-a-primer-56634/

[41] “Security Agencies Check Role Of Kerala Man In ISIS’s Kabul Attack: Report” , NDTV, March 28, 2020, https://www.ndtv.com/kerala-news/security-agencies-check-role-of-kerala-man-in-isiss-kabul-attack-report-2202227

[42] Vijaita Singh and Suhasini Haidar, “ India unlikely to allow return of 4 Kerala women who joined Islamic State”, The Hindu, June 11, 2021, https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/india-unlikely-to-allow-4-kerala-women-who-joined-is-to-return/article34792017.ece

[43] Khalid Masud, “The obligation to migrate: the doctrine of hijra in Islamic law Muhammad”, Eds Dale F. Eickelman, James Piscatori, Muslim Travellers, (New York: Routledge Press 1990).

[44]Ananya Bharadwaj, “2 top commanders killed but at least 37 Jaish terrorists still holed up in Kashmir”, The Print, August 01, 2021, https://theprint.in/india/2-top-commanders-killed-but-at-least-37-jaish-terrorists-still-holed-up-in-kashmir/707230/

[45] Vicky Nanjappa, ‘Chakravyuh: These ISIS Recruits Didn’t Know Who They Were Speaking To’, One India 14 January 2015 https://www.oneindia.com/india/chakravyuh-these-isis-recruits-didnt-know-who-they-were-speaking-to-1621263.html,

[46] Villa Dastmalchi, “The rise and fall of Islamic State’s propaganda machine”, BBC, 02 February 2018, https://www.bbc.com/news/av/world-middle-east-42824374

[47] Animesh Roul, “Islamic State Hind Province’s Kashmir Campaign and Pan-Indian Capabilities”, Jamestown Foundation, December 2020, https://jamestown.org/program/islamic-state-hind-provinces-kashmir-campaign-and-pan-indian-capabilities/

[48]Taneja and Siyech, “The Islamic State in India’s Kerala.

[49] European Union Terrorism Situation And Trend Report 2021 (TESAT), Europol, June 20, 2021,

[50] Mohammed Sinan Siyech, “India’s Foreign Fighter Puzzle”, South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies, 44, No. 1, (2021). 1- 18.

[51] Sabariah Hussin, “Preventing and Countering Violent Extremism: The Singapore Approach”, Konrad Adenuer Stiftung Report, June 2018.

[52] Siyech, India’s Foreign Fighter Puzzle.

[53] Niranjan Sahoo, “Mounting Majoritarianism and Political Polarization in India”, Carnegie Foundation, August 18, 2020.

[54] Christopher Boucek, “Saudi Arabia’s “Soft” Counterterrorism Strategy: Prevention, Rehabilitation, and Aftercare”, Carnegie Foundation, September 2008.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Dr. Mohammed Sinan Siyech is a Non – Resident Associate Fellow working with Professor Harsh Pant in the Strategic Studies Programme. He works on Conflict ...

Read More +