-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

PDF Download

PDF Download

Issac John, “The Pandemic in the Gulf: What it Portends for NRIs in the Region,” ORF Special Report No. 104, April 2020, Observer Research Foundation.

DUBAI — Battered by a triple whammy of the COVID-19 pandemic, a glut-driven oil-price plunge, and steep meltdown, Gulf countries are in a state of partial lockdown, with most economic activities at a standstill. For millions of expatriates, this sharp downturn portends a massive repatriation wave, ending a remarkable era of free-wheeling entrepreneurship, prosperity and livelihood. The COVID-19 pandemic is expected to be a key catalyst in a critical shift in the demographic landscape of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC).

Non-resident Indians (NRIs) constitute up to 35 percent of the GCC’s foreign population. It is currently home to nearly eight million Indians, who collectively account for more than 55 percent of the annual US$80 billion foreign remittances to India.

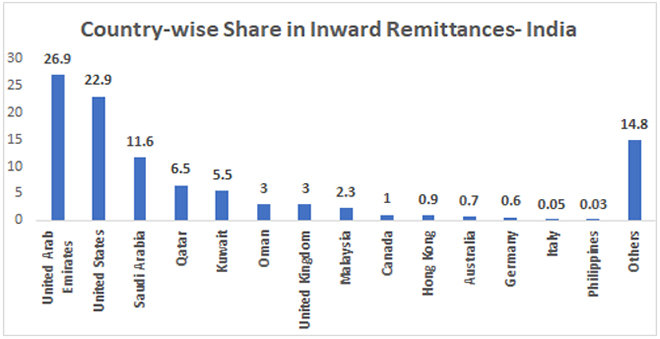

Fig. 1: Country-wise Share in Inward Remittances to India

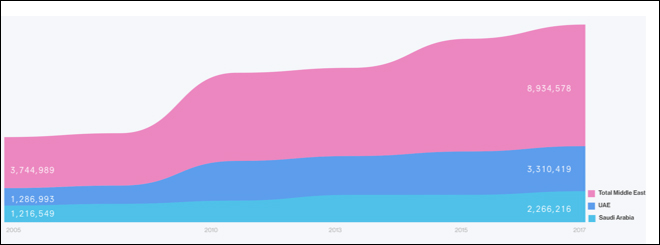

Fig. 2: Migrants from India to the Middle East

The UAE, with more than 3.3 million Indian expatriates, has traditionally been the largest source of remittances to India. According to the Reserve Bank of India, of the total remittance in 2018, the UAE’s share was 26.9 percent, Saudi Arabia’s 11.6 percent (NRI population: 1.56 million), Qatar’s 6.5 percent (NRI population: 0.692 million) and Kuwait’s 5.5 percent (NRI population: 0.825 million).

The Gulf region has been witnessing a slowdown over the last several years. Amidst an unprecedented global meltdown and regional political turmoil, it has now also been hit hard by plummeting oil revenues. Oil prices are at an 18-year low, having declined by almost 70 percent.

The International Monetary Fund Chief Kristalina Georgieva has warned that the state of the global economy appears to be far worse than the recession of 2008. According to the Asian Development Bank, the COVID-19 pandemic could cost the global economy US$4.1 trillion, the equivalent of nearly five percent of the worldwide output. Recovery is expected only in 2021.

American economist Nouriel Roubini has warned that failure to rein in the pandemic risks a worse global downturn than the Great Depression, and the best-case scenario would be a return to growth in the fourth quarter of 2020.

The impact on Gulf economies

The Gulf economies have been in fiscal deficit since 2014, with a predicted contraction of around 1.7 percent in 2020. Analysts believe that these countries appear to have finally reached the tipping point in terms of fiscal spending power, demographic composition, way of doing business and reliance on foreign labour.

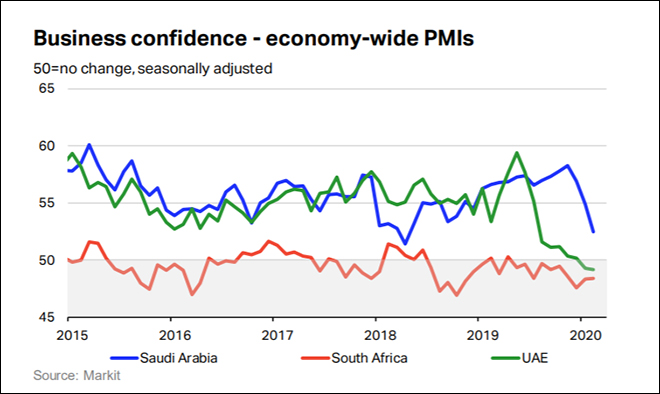

For more than five decades, NRIs have actively contributed to the buoyant economic growth of the six GCC states, but they now face the inevitable fallout of the meltdown, i.e. large-scale layoffs, widespread business shutdowns, bankruptcies and, finally, repatriation to an uncertain future in their homeland. Speaking to Khaleej Times, David Owen (Economist at IHS Markit) said, “New business volumes fell at a steep pace, driven by lower customer sales, reduced tourism, and weaker trade as countries across the world closed borders. Meanwhile, the closure of airports in the UAE and working-from-home policies, as seen across the globe, are likely to extend the downturn into April, particularly as there is no end in sight to the pandemic.” [1]

The UAE has postponed the World Expo by one year, to October 2021, while also intensifying restrictions on movement by enforcing a 24-hour curfew and a two-week lockdown.

Figure 3: Business Confidence, Economy-wide PMIs

Saudi Arabia’s Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) has hit a survey-record low amidst emergency public-health measures to prevent the spread of COVID-19.

The Central Bank of the UAE responded to the outbreak with a comprehensive DH256 billion stimulus package to help retail customers and corporates, and is now closely monitoring job cuts in the financial sector.

To stay afloat, most employers in the private sector are resorting to salary deductions of up to 50 percent, leave-without-pay policies, and moderate to massive layoffs. Cash-strapped companies are reaching out to banks to address immediate liquidity problems to pay employees’ final settlements.

The impact on the aviation sector

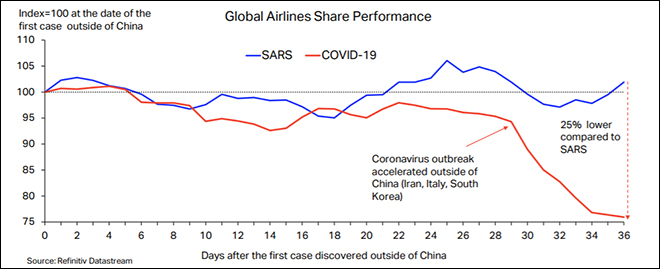

During the 2003 outbreak of SARS-CoV, the aviation industry was one of the worst affected, taking a US$7 billion hit, as attested by the International Air Transport Association (IATA). [2] Considering the rapid spread of COVID-19 and the subsequent failure of the global community to respond with adequate urgency, financial markets have estimated that global airline profits will decrease dramatically, much more than in 2003.

Figure 1: Global Airlines Share Performance

According to Standard & Poor’s, the pandemic could reduce global air passengers by up to 30 percent in 2020. The latest data from the IATA shows that COVID-19 will lead to an estimated loss of US$252 billion in passenger revenues in 2020. According to their estimates, the UAE airlines will lose 23.8 million passengers, with a loss of US$5.36 billion in revenue, 287,863 jobs, and US$17.7 billion in contribution to the national economy; Saudi airlines will lose 26.7 million passengers, with a loss of US$5.61 billion in revenue, 217,570 jobs, and US$13.6 billion in contribution to the kingdom’s economy; Qatar will lose 3.6 million passengers, with a loss of US$1.32 billion in revenue, 53,640 jobs, and US$2.1 billion in contribution to the state’s economy. As of 11 March 2020, Middle Eastern airlines have already lost US$7.2 billion in revenue. Most airlines and hotels in the GCC have announced layoffs, wage cuts and flight cancellations.

The travel, aviation, tourism and hospitality sectors — which constitute the mainstay of the UAE’s private-sector economy — have been the worst-hit in the meltdown. Following the nationwide closure of all airports and the suspension of outbound and inbound flights in March, the UAE’s once-vibrant aviation scene has come to a halt, forcing flagship carriers Emirates Airlines; Etihad Airways; Air Arabia; flydubai; and the new-born, low-cost carrier Air Arabia Abu Dhabi to tread water through cost-cutting measures, including sending their staff on leave. Emirates Airlines, Etihad Airways and flydubai have announced temporary salary cuts, by 50 percent on management wages and 25 percent on other staff salaries. Sheikh Ahmed bin Saeed Al Maktoum (Chairman and Chief Executive, Emirates Group) has assured employees that they will continue to be paid all other allowances during this time; moreover, junior-level employees will be exempt from basic salary reduction.

The Saudi Arabian Monetary Authority (SAMA) wants banks to immediately put in place a lending programme for at least six months to assist in maintaining employment levels. Further, in a circular released in March, SAMA directed banks to provide relief on debt repayments to any customers that have already been dismissed. [3]

The United Nations has said in an appeal that six billion people living in developing economies will urgently need a US$2.5 trillion “rescue package” to mitigate the economic fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic. To this end, Gulf economies have been rolling out stupendous economic stimulus packages and quantitative easing measures. The UAE has unveiled a DH127 billion stimulus package, while Saudi Arabia has announced SAR120 billion in support.

The impact on NRIs in the Gulf

According to analysts, the writing is on the wall. The era of boom and dream-like fortunes for expatriates is now coming to an end. In the wake of plunging oil prices amidst demand destruction and deepening global recession, their wealth is fast depleting and liquidity drying up. Consequently, the GCC nations have expedited the process of reducing their dependency on foreign labour, an unavoidable eventuality that will have far-reaching implications on the nine million NRIs across the oil-rich region.

Economists have warned that COVID-19’s social impact on the Gulf’s transnational labour will be exponential. The impending risk of job loss will affect the employed class of NRIs: blue-collar workers, who constitute 25–30 percent of NRIs in the Gulf; lower- and upper-middle-income employees, who account for 40–50 percent; and high-paid professionals. According to analysts, in the best-case scenario, only 15–20 percent of the employed class will face imminent job loss by the end of April. However, without any signs of relief and the extent of the pandemic’s fallout remaining uncertain, by July, job losses could snowball to 50 percent across all nationalities and various sectors, including travel, hospitality and tourism; retail; SMEs; construction; logistics and cargo; education; and healthcare.

For most SMEs and up to 80 percent of large businesses, it is a catch-22 scenario. The GCC is currently witnessing the worst downturn since the 1980s. Businesses are hard-pressed to survive, with little revenue and no option for a safe exit. Across the region, corporations and businesses — both small and medium enterprises as well as large companies — are increasingly reaching a point of no return, reeling under the knock-on effect of payment defaults, a liquidity crunch, bounced cheques, tightening credit squeeze by lenders, overdue salary payments, missed value-added tax (VAT) payment deadlines, rentals, and various government fees.

The Gulf’s business sector, dominated by NRIs, has been facing substantial headwinds over the last few years. In 2014, the oil economies — at the time steadily recovering from the fallout of the Global Financial Crisis — faced an oil-price plunge, which subsequently affected their fiscal revenues. In late-2016, the OPEC (with new partners such as Russia and Mexico) responded with production cuts that held prices steady in the range of US$50–70 per barrel, until the agreement fell through on 5 March 2020. [4] Since then, oil prices have been in free fall, having now dropped to under US$20 per barrel. [5] During the sharp fall in oil revenues, the structural fundamentals were similar to what members of the OPEC+ (Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries) observed in early March 2020: declining demand in China and a persistent supply from American producers. However, what is different from the price volatility five years ago — and what the Saudis and Russians could not have fully foreseen — is the demand destruction caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, which has wreaked havoc on the largest economies in the world. [6]

As COVID-19 cases continue to rise sharply in the Gulf, governments are taking drastic steps to enforce social distancing by announcing curfews, travel bans and the shutdown of large segments of their economies. Economists believe that these measures are already leading to severe economic disruption and will continue to do so over the coming weeks and months. The severity of the economic impact in the GCC will largely depend on two factors: a) the duration of restrictions on the movement of people and economic activities; and b) the size and efficacy of fiscal responses to the crisis. Since most governments have implemented well-designed fiscal stimulus packages and prioritised health spending to contain the spread of the virus, experts are hopeful that the likelihood of a deep economic recession can be minimised.

Due to the oil-price collapse and the COVID-19 outbreak, Moody’s has changed its outlook from stable to negative for the banking systems of Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Kuwait, Qatar and Bahrain, and has maintained its negative outlook on the banking system of Oman. In most of the GCC states, banks have been instructed to waive loan repayments, and in some countries, firms have been exempted from tax and utility payments. However, the collapse in oil prices has put the Gulf governments in a bind. With Brent crude below US$30 per barrel, budget and current accounts will fall into deficit across all six economies.

Economists argue that the signs of a sweeping shift across the Gulf’s labour markets have never been as tangible as during the current crisis. The last oil market downturn spurred a series of policy shifts, such as the “nationalisation” of jobs in certain sectors, more flexible visas, new taxes and fees on the backs of foreign workers, and vast purges of low-wage workers in construction. [7] However, the new nationalisation policies across the GCC are meant to encourage and safeguard certain jobs for citizens. Already, tens of thousands of Indian expatriates have been repatriated due to Saudisation, or Nitaqat. The kingdom has strictly reserved employment for nationals in several retail and hospitality sectors, from mobile phone shops to eyeglass stores. [8] The decline in government contracting — a cyclical normality for the GCC economies when oil revenues drop — was especially sharp between 2015 and 2018, when as many as 700,000 foreign low-wage workers were laid off in Saudi Arabia. Oman has now banned expatriates from working in more than 80 job categories. So far, the UAE, Kuwait, Qatar and Bahrain have restricted the job nationalisation drive to government jobs.

In the wake of the slowdown sparked by the oil-price plunge over the past few years, some governments have enacted taxes and fees to turn foreigners into new sources of revenue, e.g. introduction of road tolls; visa renewal fees; [9] and excise taxes on alcohol, tobacco and sugary drinks. The UAE and Saudi Arabia have introduced a five-percent VAT, while scrapping subsidies on fuel as part of the economic diversification measures.

A key shift in residency laws has resulted in foreign workers across the Gulf being scrutinised by respective governments for their utility as consumers and sources of government revenue in taxes [10] and fees. The expatriates with investment potential as real-estate buyers or highly skilled experts [11] have received some privileged residency status opportunities.

Across the globe, governments are seeking policy measures to ease the burden on workers. However, as unemployment surges in the service and retail sectors, the GCC governments have little incentive to provide cash supplements to displaced workers, since most of them are foreigners. Saudi Arabia has ordered up to US$2.4 billion to be disbursed for the partial payment of the wages of private-sector workers, to deter companies from laying off staff. The UAE has enacted a new regulation that lets employers make workers redundant but mandates them to provide housing and allow the employee to transfer their visa to a new employer if a new position is found. [12] Further, employers can temporarily reduce salaries or force employees to take paid or unpaid annual leaves. Saudi Arabia has announced partial salary support for citizens working in the private sector who have been made redundant, but this does not extend to foreign residents. [13]

To tide over the challenges, the GCC governments are responding with stimulus packages that provide liquidity to the banking sector and minimal support to small- and medium-sized businesses. [14]

The UAE cabinet has approved the extension of residence permits expiring on 1 March 2020, for a renewable period of three months, without any additional fees upon renewal. Effective 24 March 2020, the UAE also made temporary amendments to insolvency and corporation laws in response to the challenges that businesses are facing due to the COVID-19 crisis. According to legal experts, these amendments provide a safety net that enables businesses to survive once the crisis has passed. The government intends to reduce the risk of businesses being unnecessarily pushed into insolvency and of personal liability for insolvent trading as a result of debts incurred in the ordinary course of business. For the UAE bankruptcy regime, it is reasonable to assume that within the government’s contemplation, these measures act as temporary relief for businesses.

The Abu Dhabi Executive Council has launched a new set of initiatives, including a series of stimulus packages to boost SMEs and to ease the availability of loans to local companies. Dubai has announced a DH1.5 billion economic stimulus package, including measures to protect businesses, especially in tourism, retail and external trade, and logistics services. Such measures include a freeze on the 2.5-percent market fee for all facilities operating in Dubai and a refund of 20 percent on the customs fees imposed on imported products sold locally in Dubai markets. Qatar, too, has announced several supporting measures and incentives for the local business community, amounting to QAR75 billion.

An online survey by the data analytics firm YouGov [15] shows that 92 percent of working professionals in the UAE believe that the pandemic has had a large or moderate impact on their business. Further, 32 percent of the respondents feel that businesses will take a month or less to recover from the setbacks once the situation is resolved; 17 percent believe that it could take four to six months; and 13 percent think it could take more than six months.

Issac John is Editorial Director of Khaleej Times.

[1] Issac John, “Covid-19: Top Mena economies track global economic slowdown in March”, Khaleej Times, 5 April 2020.

[2] “Economic Briefing Avian Flu”, IATA, May 2006.

[3] Bloomberg, “COVID-19 response: Saudi Arabia tells banks to go easy on loans”, 30 March 2020, Gulf News.

[4] Rania El Gamal, Alex Lawler and Olesya Astakhova, “OPEC’s pact with Russia falls apart, sending oil into tailspin”, Reuters, 6 March 2020.

[5] Al-Monitor Staff, “Mideast oil producers brace for impact of price slide”, Al-Monitor, 10 March 2020.

[6] Ben Casselman and Patricia Cohen, “A Widening Toll on Jobs: ‘This Thing Is Going to Come for Us All’”, 3 April 2020.

[7] Karen E. Young, “Mapping economic diversification across the Gulf Cooperation Council”, American Enterprise Institute, 13 September 20019.

[8] Vivian Nereim, “Saudi Arabia to Ban Foreigners from Slew of Hospitality Jobs”, Bloomberg, 28 July 2019.

[9] Kareen Fahim, “Saudi Arabia encouraged foreign workers to leave — and is struggling after so many did”, The Washington Post, 2 February 2019.

[10] Tawfiq Nasrallah, “Excise tax rates in the UAE: What you need to know about sugary drinks, cigarettes and other products”, Gulf News, 5 December 2019.

[11] “GCC Employment and Immigration law update May 2019”, PWC, 14 May 2019.

[12] “New Ministerial Resolution relating to employment and COVID-19”, Al Tamimi & Co., 31 March 2020.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Karen Young, “GCC responds to twin crises with financial rescue packages”, Castlereagh Associates, 20 March 2020.

[15] Zafar Shah, “Most UAE professionals expect a long recovery period for their businesses to overcome COVID-19”, YouGov, 2 April 2020.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.