The union budget 2023 has been marked by its welfare implications, impetus for consumption-driven growth through personal income tax rationalisations and creating enabling conditions for private investments by increasing the capital expenditure.

The most positive underlying message of the

budget is that by underscoring the seven principles, namely, Inclusive Development, Reaching the Last Mile, Infrastructure and Investment, Unleashing the Potential, Green Growth, Youth Power, and Financial Sector, the budget has attempted to unleash forces in which the fundamental principle of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are embedded, i.e., addressing the irreconcilable development trinity of equity, efficiency and sustainability.

With the inclusion of green growth in the annual budget, India has made its stance clear about its green ambitions.

With the inclusion of green growth in the annual budget, India has made its stance clear about its green ambitions.

By making green growth as an explicit pillar, an important message has been sent to the broader civil society: India is extremely serious about its green ambitions.

But what are the explicit and implicit green messages of this Budget? Do the budget proposals have more green implications than what meets the eye? What are the future implications?

Green growth and increasing capital expenditure

For the first time, the term “green growth” has found such emphatic mention in a budget. While prima facie, this looks to be a major cause of cheer for the “green warriors” and the environmentally conscious from among the civil society, one often tends to overlook the flip side of it.

Globally, the notion of “green growth” is often envisaged as a position that can reconcile between the needs of development and conservation goals. In the process, it is largely contingent upon the decoupling of the use of natural resources and economic growth. An undeniable fact of the present civilisation is that human progress is inextricably linked with the use of one of the most fundamental forms of capital: natural capital. Therefore, the very decoupling of growth from natural capital or resources provided by nature is practically and axiomatically impossible. This is exhibited in a

2016 paper by Ward et al where the authors, on the basis of an analytical macro-model, infer the following, “… growth in GDP ultimately cannot plausibly be decoupled from growth in material and energy use, demonstrating categorically that GDP growth cannot be sustained indefinitely. It is therefore misleading to develop growth-oriented policy around the expectation that decoupling is possible. …The mounting costs of “uneconomic growth” suggest that the pursuit of decoupling–if it were possible–in order to sustain GDP growth would be a misguided effort”.

An opencast coal mine in India. The decoupling of natural resources and the economic growth is practically impossible in the current scenario where human progress is inextricably linked with natural capital.

An opencast coal mine in India. The decoupling of natural resources and the economic growth is practically impossible in the current scenario where human progress is inextricably linked with natural capital.

This “lack of decoupling” phenomenon is apparent in the Indian context, at least the way the budget proposes “green growth”. It needs to be understood here that the Indian notion of “green growth” is largely based on “green transition”, i.e., energy transition from fossil fuel to renewable sources. Here the concern of biodiversity or natural capital hardly features. Rather, the increasing capital expenditure as proposed in the budget will entail creation of large-scale infrastructure that will bring about land-use change thereby shrinking green spaces and carbon sinks (both carbon stocks and annual carbon sequestration capacity). This will go against climate action. This aspect has neither been noticed in the union budget, nor has been discussed in the public domain so far.

Adaptation funds

The budget has given a lot of emphasis to mitigation component of climate action. This becomes evident from profuse mentions of green growth, renewable energy, National Green Hydrogen Mission, energy transition and storage, and Green Credit Programme. However, there is no mention of the term “climate adaptation” anywhere in the budget speech.

It is a fact that India has declared an important green ambition, in the form of being “net zero by 2070”, which is also in consonance with its development ambitions. But there are vulnerable regions that are reeling under the pressure of global warming and climate change:

certain parts of coastal eastern India might subside under the Bay of Bengal due to sea-level rise by 2040/2050 under specific scenarios, and mitigation efforts through green transition will not help their cause. This requires adaptation, either through accommodative infrastructure or through

managed retreat. On the other hand, globally, there has been an

inherent funding bias in favour of mitigation projects as against adaptation projects. Hence, there should have been public expenditures on this component, especially at a time when private players are apprehensive in getting into the adaptation space due to lack of perceptible “returns” in the short run. From the perspective of creating public good, this is a costly miss in the union budget.

Mission Millet

Mission Millet’s budgetary provisions will undoubtedly go a long way from the perspective of both water and nutritional security. It was in a 2009

paper in the journal

Water Policy, I, along with my co-author, Jayanta Bandyopadhyay, showed how shifting from paddy to ragi during the summer in the Cauvery basin, can help in resolving water conflicts. A

2019 paper in

Frontiers in Environmental Science estimates the amount of water savings for keeping water in-stream, the resulting increase in ecosystem service values, and increase in farm incomes when cropping acreage shifts from wheat to sorghum. In that sense, millets can change the “water equation”: it can reduce conflict intensities between competing groups through water demand management and reverse the existing trade-off between farm incomes and ecosystem concerns.

Source: D’souza et al (2022).

Source: D’souza et al (2022).

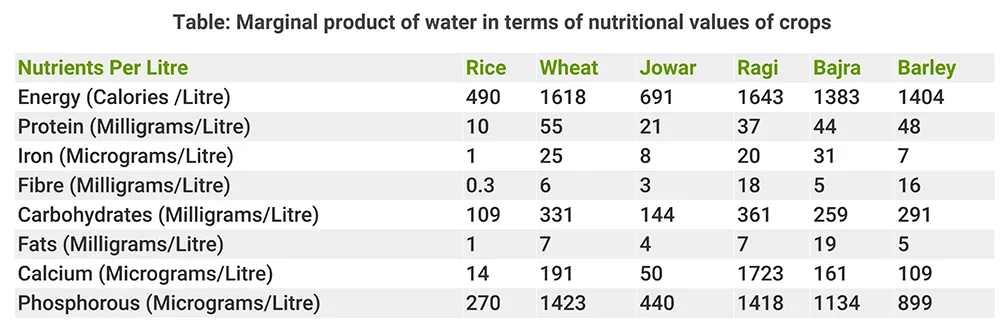

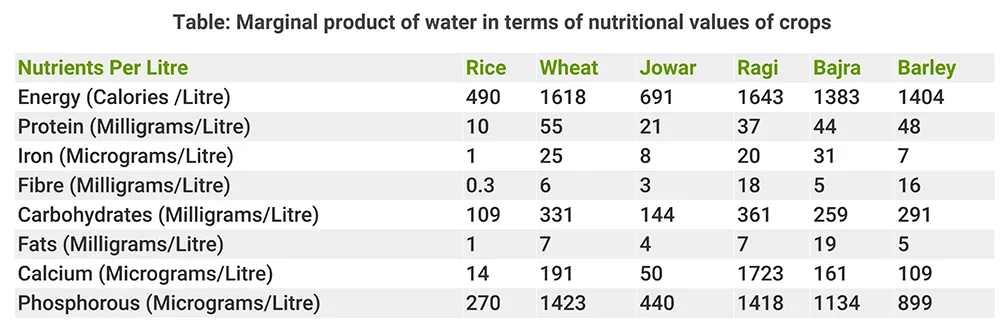

However, millets also have nutritional security implications. A

recent paper published by researchers of Observer Research Foundation estimates the marginal product of water (defined by increase in product quantity with a unit increase in water use) in terms of nutritional values of different crops.

Ragi is the most efficient water user in producing calories. Bajra followed by wheat and ragi are among the top performers in terms of water efficiency in producing iron. Again, ragi is the most water efficient in terms of fibre production. ragi emerges as the second-most efficient water user in producing carbohydrates, and the top performer in the case of calcium production. Wheat and ragi perform equally well with phosphorus production with increased use of a unit of water. This creates every case for promoting millets.

Community participation in natural resource management

In what turned out to be a very interesting Budget speech from a sustainable development perspective, was made further interesting with FM’s acknowledgment of the roles of local communities in conservation efforts. However, the FM could have gone further by announcing a budgetary allocation to incentivise local community for their important roles in conservation and to play such roles more actively. There are important lessons from

global experiments with ecosystem markets through creation of PES (Payment for Ecosystem Services). By doing so, three apparently conflicting goals could have been served at one go: conservation goals, generate incomes for community, and finance sustainable development not only through government expenditures but also by attracting complementary private investment. However, this can always be taken up in future budgets.

Green bonus

In a 2019 conclave of the Himalayan states at Musoorie (Uttarakhand), ten Himalayan states (namely, Jammu & Kashmir, Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh, Sikkim, Arunachal Pradesh, Meghalaya, Nagaland, Tripura, Mizoram, and Manipur) signed the Mussoorie Resolution and pledged to conserve the Himalayan ecosystem. In return, they placed two demands before the Union finance minister: first, creation of a separate ministry to deal with problems of the Indian Himalayan region, second, a green bonus for these biodiversity-rich and seismically and meteorologically fragile states. There is no doubt that this is a novel idea from the perspective of incentivising states to maintain their green cover. Such ideas may be extended to coastal states, as also states endowed with substantial natural capital often described as

blue-green infrastructure. There needs to be a thinking in this direction in future budgets so that the concerns of biodiversity are configured into the Indian developmental policies.

A damaged road in Joshimath, Uttarakhand. The demands made by Himalayan states in India are important from the perspective of incentivising states to maintain their green cover and to preserve the fragile ecosystem.

A damaged road in Joshimath, Uttarakhand. The demands made by Himalayan states in India are important from the perspective of incentivising states to maintain their green cover and to preserve the fragile ecosystem.

Path ahead

It is evident from the union budget 2023 that environmental concerns are dawning into India’s developmental thinking. But more can be done. Future budgets should think of

Green Budgeting and promoting

Green Accounting by readily acknowledging the values of the biodiversity through their ecosystem services. The Chapter 5 of the

report of the expert committee constituted by the Supreme Court of India (of which I am a member) revised the formula for estimating Net Present Value (NPV) of Indian forests. This state-of-art formula can be the entry point for promoting green accounting/ budgeting in the Indian development policy thinking.

This commentary originally appeared in Mongabay.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV