-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

PDF Download

PDF Download

Aditi Ratho, “The Future of Care Work Post-COVID-19,” ORF Occasional Paper No. 330, September 2021, Observer Research Foundation.

Introduction

The term ‘care economy’ encompasses both the informal and formal care markets, referring to unpaid and paid care services, such as family care responsibilities, the care of dependents through education, nursing, child and eldercare, and work in the formal healthcare sector.[1] According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), “care” is the activity that “provides what is necessary for the health, wellbeing, maintenance, and protection of someone of something”[2] and “work” is an activity that involves “mental or physical effort and is costly in terms of time and resources”.[3] According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), formal healthcare, services for childcare, early childhood education, disability and long-term care, and eldercare are areas that comprise the care sector.[4] The care economy is a unique sector that focuses on developing intangible benefits in human and social capital that are hard to quantify in a market. Unlike sectors of the economy that may produce tangible physical goods, there are no standardised metrics to measure productivity, impact and value of care work.[5]

By 2030, women could gain 20 percent more jobs in the care sector than present levels, and on average, 58 percent of gross job gains by women could come from healthcare and social assistance.[6] However, this will only be the case if women can escape unpaid or underpaid work and informal labour. Informal labour here refers to “all remunerative work (i.e. both self-employment and wage employment) that is not registered, regulated or protected by existing legal or regulatory frameworks. Informal workers do not have secure employment contracts, workers’ benefits, social protection or workers’ representation.”[7] According to a 2019 survey on the ‘Future of Women at Work’, women are less mobile and flexible to partake in new work opportunities because they spend over 1.1 trillion hours a year on unpaid care work compared to less than 400 billion hours for men.[8]

Despite the wide-reaching social benefits of care work, care workers can be at the receiving end of a ‘care penalty’, experiencing an undervaluation of their work. The care penalty arises as care work is economically undervalued. Care workers provide labour-based services that develop or help maintain human capital. Investments in human capital through care work are often intangible and with benefits reaped in the long term and are thus hard to capitalise and quantify in conventional measures, such as gross domestic product (GDP). In both paid and unpaid care markets, the care penalty inherently burdens women as the care economy is disproportionately female. Unpaid care work, according to the OECD, refers to “all unpaid services provided within a household for its members, including care of persons, housework, and voluntary community work.”[9]

In developing countries like India, “underpaid” care work comes under scrutiny as domestic and community health workers take on the household and healthcare burdens for meagre remunerations. Even though they are ‘paid,’ their services are exploited without adequate compensation. In India, there is a blurred distinction between care work and domestic work. According to the 2019 Indian National Survey Sample report on time use, women spend 299 minutes a day on unpaid domestic services compared to the 97 minutes spent by men.[10] In the July-September 2020 periodic labour force bulletin,[11] total unpaid helpers in household enterprises account for 5.4 percent of workers aged 15 and above (up from 5.0 percent in January-March 2019). Of these, women comprise 10.7 percent (up from 9.2 percent in January-March 2019), and men 4.0 percent (a minor increase from 3.9 percent in January-March 2019).[12]

In 2018, the ILO reported that the 16 billion hours spent on unpaid caring every day would represent nearly a tenth of the world’s entire economic output if paid at a fair rate.[13] According to the World Economic Forum’s Gender Gap Report, 66 percent of women’s work in India is unpaid as opposed to 12 percent for men.[14] In the UK, nearly three‐fifths of unpaid carers are women, and they are more likely than men to be caring for someone living in another household.[15] In the US, care workers are often employed with low wages and without benefits like health insurance and retirement security and are disproportionately black, Latinx, and immigrant women, who all have the additional burden of insufficient legal rights and protections.[16]

Studies have estimated that women’s unpaid contributions to healthcare equate to 2.35 percent of global GDP, or about US$1.488 trillion.[17] If the net of ‘care’ is widened beyond just health, this number rises to a whopping 9 percent of global GDP (or US$11 trillion).[18] Data also shows that adolescent girls spend significantly more hours on domestic work than adolescent boys, which can have a negative impact on their education.[19]

According to economist Minouche Shafik, a large part of why the current social contract is failing social circumstances is that women are still expected to look after children and older people for free.[20] Although more women go to university than men, issues like wage gaps in formal employment exist because of regressive maternal leave policies instead of inclusive parental leave policies and a lack of state-led financing of childcare.

The COVID-19 crisis has highlighted that 70 percent of the paid global healthcare workforce is female.[21] This does not account for those who work behind the scenes in maintaining the health and wellbeing of children, older persons, and other family members on an unpaid basis. The pandemic has brought about a unique dilemma of countries facing an acute shortage of healthcare facilities, together with the growing loss of jobs in the care sector. The closure of schools and workplaces has led to the closing of day-care centres, leaving care workers (who are paid minimum wages with little or no benefits) stranded. Not only have ‘formal’ and ‘semi-formal’ workers lost their jobs, but the pandemic has also exacerbated the informal care economy as women previously in formal jobs have had to take on the double burden of unpaid care and domestic work, being restricted to the confines of the home and existent social norms. Additionally, undervalued and underpaid care workers, such as caregivers and aides, work in poor conditions with limited protections and low wages.[22]

Experiences and learnings from previous epidemics show that rapidly rising infections catapult more women and girls to take on a larger portion of unpaid or poorly paid care work in families and communities. For instance, during the Zika epidemic, women in the Dominican Republic were solely responsible for caring for sick family members in 79 percent of cases, and only 1 percent of respondents reported that men bore the burden of caring for children and older persons in their families.[23] The Ebola crisis in Liberia revealed that women primarily monitored the health of family and other community members. Among the large number of women who form part of the global health workforce, community health workers (70 percent of which are women in sub-Saharan Africa)[24] are on the frontlines of the global health response but the most neglected—they are unpaid, without benefits or regular contracts, but working long and tiresome hours.

The COVID‐19 pandemic has disrupted work for the already overburdened care workers, with many informal, part‐time, and seasonal workers losing jobs. This paper analyses the gendered impact of the pandemic on care workers in both the informal and formal sectors and the measures required to safeguard them during any potential future waves of the pandemic and beyond.

Impact of COVID-19 on Care Workers

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a disproportionate impact on the care workforce, and consequently women, due to several reasons. For instance, women comprise a large percentage of care and essential workers that are at the frontline of the pandemic; the informal nature of these jobs force women out of the workforce altogether; the closure of childcare facilities, which affects working mothers who may then have to drop out of the workforce.

Additionally, many care workers have reported emotional and mental trauma, burnout, and disillusionment during the pandemic, and polls show that around a third of the workforce has seriously considered leaving the sector entirely.[25] Vast numbers of health professionals working with COVID-19 patients also reported experiencing post-traumatic stress, depression, anxiety, and insomnia.[26]

Research in 16 countries shows that women spent an average of 26 hours per week looking after children, compared to 20 hours a week for men, before the pandemic. This has risen by 5.2 hours for women and just 3.5 hours for men during the pandemic, equivalent to a full-time job.[27] An October 2020 report by The Century Foundation and the Center for American Progress showed that the US risks losing approximately US$64.5 billion in economic activity from women’s aggregate wage loss due to the lack of childcare and their need to reduce hours or leave the workforce. This ‘lack of childcare’ was a result of the sector losing more than 350,000 jobs in a single month at the beginning of the pandemic.[28] The lack of childcare has been a consequence of school closures, affecting 1.37 billion students (72.4 percent) across 177 countries,[29] where caring for children has moved from the paid economy to the unpaid economy.

Domestic work broadly provides personal and household care,[30] is often part of the informal economy and is usually bereft of social security and employment benefits. During COVID-19, domestic workers have been dismissed without compensation, a safety net, or adequate skills for other jobs. Those who continued to work reported difficulties commuting to workplaces during lockdowns, heavier workloads, and limited protection from infection. Still, domestic work remains an important source of income for women, comprising 14 percent of female employment in Latin America and 11 percent in Asia.[31]

Of the world’s 67 million domestic workers (above 15 years), 80 percent are women and approximately 11 million are migrants.[32] Migrant domestic workers typically reduce native women’s burden of care work and thus help increase female labour force participation in the host country, even as they simultaneously entrench class and race divisions. This form of migration is touted as a global ‘care chain’ where care labour from low and middle‐income countries in Asia, Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean is transferred to North American countries, most Western European nations, and developed parts of Asia.[33] While global care chains do plenty for the sending nations (in the form of remittances) and for the receiving country (in the form of relieving the burden of work), tighter border controls and stricter immigration laws during and after the pandemic will have significant repercussions on the labour market. For instance, the lack of supportive policies for migrant care workers in the host country will result in such workers returning to their home nations, causing a shortfall of care workers in the recipient country, in turn triggering a greater number of women giving up formal work to perform unpaid domestic care work.

The pandemic has caused uneven, gendered damage to formal and informal care workers. The healthcare and essential workforce has emerged as the indispensable backbone of the economy, and much of the conversations surrounding labour reforms and protection have such workers at the core. The disproportionate number of women essential and informal workers reflects in the disproportional impact of the virus. For instance, a survey conducted in South Africa on employment, hunger and health (the ongoing National Income Dynamics Study Coronavirus Rapid Mobile Survey) shows that in February-April 2020, between 2.5 and 3.6 million fewer people were employed and there was an 18 percent decline in employment, with women, self-employed workers and informal casual workers most severely impacted.[34]

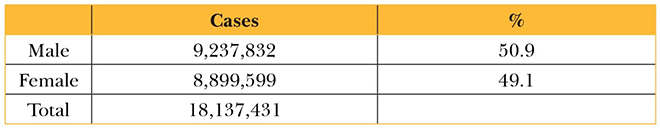

Countries have not made a rigorous and sustained effort to collate periodic and consistent sex-disaggregated data on COVID-19 cases and deaths. As of 18 January 2021, the UN Women’s dashboard on gender-based COVID-19 only had data for 19 percent (18,137,431) of all reported cases (93,194,922), based on reporting from 137 countries, areas and territories (See Table 1). Among these cases, 49.1 percent were female and 50.9 percent were male (45.7 percent female and 54.3 percent male in June 2020).[35]

Table 1: Sex-disaggregated COVID-19 cases (as of 18 January 2021)

Source: Created by the author from UN Women data

Among the 18,137,431 cases, although men are affected more in terms of overall COVID-19 infections, the percentage of women healthcare workers affected is far higher. Consequently, a higher number of female essential and healthcare workers has resulted in more cases amongst them.

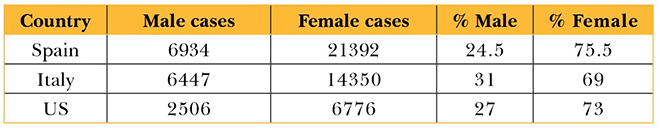

In June, data from UN Women showed that in countries like Spain, Italy and the US, COVID-19 infections among female healthcare workers were twice that among their male counterparts (see Figure 2).

Table 2: Healthcare workers infected in Spain, Italy and US

Source: Created by the author from UN Women data

An April 2020 analysis of census data[36] crossed with the US federal government’s essential worker guidelines revealed that approximately 33 percent of jobs held by women are deemed essential compared to 28 percent for men, meaning more women are at the frontlines and exposed during the pandemic.

India has about four million community health workers (CHWs)—1.03 million Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA) workers[37] (who are all female) and 2.7 million anganwadi (rural childcare centre) workers and helpers.[38] ASHA workers’ responsibilities include promoting immunisation, creating awareness on health, and providing referrals for the health of women and children.[39] They are the first point of contact at the local level for any health-related concern, including pregnancy-related counselling. The anganwadi system was first set up to look over cases of malnutrition present in women and children under the Integrated Child Development Services Programme.[40] Anganwadi workers provide support for children and pregnant women, educate mothers on breastfeeding and nutrition, and oversee the distribution of rations to young mothers and children to receive adequate nutrition.[41]

COVID-19 has highlighted that ASHA workers lack a formal employee status in the health system and are severely underpaid, with their work considered voluntary and part-time.[42] Nevertheless, ASHA workers have seen their work deliverables increase exponentially during the pandemic. They have had to visit houses, identify potential cases, document travel details, coordinate the delivery of essential items to quarantined households, track migrants returning home, and help in the vaccination drive. Importantly, ASHA and anganwadi workers have been crucial to collecting and documenting local data that has helped gauge national trends.

In areas like Nagpur, CHWs have protested to avail a fixed salary at the state level pay scale instead of arbitrary ‘monthly compensation’ during the pandemic.[43] ASHA workers in Punjab do not receive a salary as they are not employees of the state, but get incentives from the union health department if they fulfil specific quotas for testing or vaccination.[44] Kerala has a seen delayed payments to ASHA workers, and since they report to primary healthcare centres (that may be located at a distance), the cost of travel and increased exposure to the virus during the journey are additional burdens to bear.[45]

The Ministry of Women and Child Development has conducted online sessions for CHWs on safety during the pandemic,[46] but the effort has been limited due to a lack of access to the internet and digital devices. Furthermore, reports suggest ASHA and anganwadi workers have paid out of their own pockets for the smartphones needed to fill out COVID-19 surveys and details.[47] Many CHWs have also had to work without or with inadequate protective gear and combat the prejudice that comes with being at the frontlines of COVID-19 mitigation efforts.[48]

Essential and informal healthcare workers must be brought under the ambit of formal healthcare and provided employee benefits and protection to explicitly acknowledge and account for the tremendous tasks they perform during health crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic. This includes better and fixed pay, as opposed to arbitrary incentives and honorariums that can be delayed ad nauseam; investment in providing digital equipment and digital skilling with which contract tracing, surveys, and reports can be done seamlessly; and the provision of protective gear at the same level as formal healthcare workers.

Robust data on the number of health workers affected per country is essential across all categories—doctors, nurses, sanitation workers, CHWs—to chart a blueprint to rehabilitate the affected. COVID-19 has exposed the double burden in care work and essential work that women are undertaking, resulting in physical and emotional duress. A focused redistribution of work is in order so that differences in experiences do not result in inequality in management and treatment.

Skilling for Care Work

By 2030, women are predicted to gain 20 percent more jobs than present levels; on average, 58 percent of these gross job gains could come from healthcare and social assistance.[49] In the US, for instance, labour demand in the healthcare sector is projected to grow 2.4 million jobs by the end of 2029, placing it among the fastest-growing occupations.[50] The projected growth of the healthcare sector can be attributed to factors like an increasing life expectancy and an ageing population. In addition, the aftermath of the pandemic is also expected to contribute to the growth of the sector, as people pay greater attention to healthcare needs.

Countries will have to take stock of existing skilling and social security policies to bring informal care workers into the formal system and account for disruptions. This will need to start with evaluating the terms ‘care work’ and ‘care workers’ in country-specific labour force surveys. For example, in South Africa, a substantial proportion of care work is delivered through non-profit and non-governmental organisations, and women perform the majority of the paid and unpaid care work; where it is paid, women are often underpaid, and their services are undervalued.[51] Still, Statistics South Africa’s Quarterly Labour Force Survey does not define a separate industry category for the care sectors; instead, it captures these workers within the larger subset of community, social and personal services category.[52] Having a defined category would mean inferences can be legitimately drawn for how many more workers are needed to strengthen care systems, how many will be affected by changes in care systems and disruptions, and how many will need to be reskilled or upskilled.

South Africa is an important example because the country is among the hardest hit by the pandemic in Africa, and by November 2020, comprised close to 40 percent of the total cases on the continent.[53] Since 2011, CHWs in South Africa have received formal, rigorous training that includes two 10-day short courses followed by a one-year National Qualification Framework Level 3 Health Promoter qualification,[54] together with the requirement of a grade 12 certificate. However, in many areas, CHWs are directly recruited by non-profit and non-governmental organisations and therefore continue to work under precarious conditions with minimal access to formal training.[55]

Thus, though policies have attempted to formalise training for CHWs, the distribution of training is inadequate, and remuneration remains disparate based on whether they are employed by non-profit and non-governmental organisations, the state, or government departments. Furthermore, even after formal training, CHWs are still recruited on a contractual basis, without fixed pay (like India’s ASHA workers).[56]

While formal training for care workers must increase to bring workers into a formal employment system, countries must ensure that the distribution of such training is not skewed just towards women, thereby perpetuating gendered impacts of health crises.

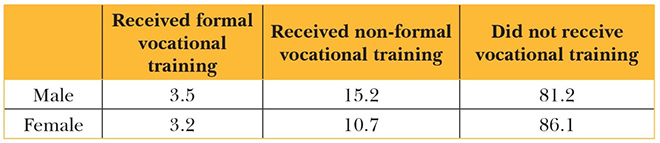

In formal and non-formal vocational training in India, a higher percentage of males than females received vocational/technical training (see Table 3).[57]

Table 3: Working Age (15-59 years) Males and Females Receiving Vocational and Non-Vocational Training in India (in percentage)

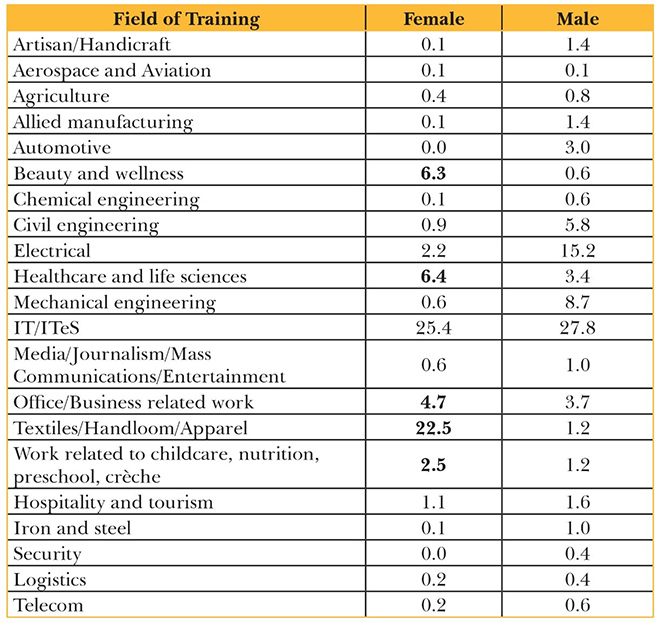

The field of vocational training that men and women receive signifies the specific area of training that a person obtained (see Table 4). Data shows that more men than women received training in 16 of the 21 sectors, and the sectors that had a larger number of women receiving vocational training are the traditionally ‘feminine sectors’ like beauty and wellness, office related work, textiles and handloom. ‘Care’ work—defined by this paper to include healthcare and work related to childcare, child nutrition, preschool and creche—was also higher for women than men.

Table 4: Field of Vocational Training in India—Working Age (15-59 years) Males and Females (in percentage)

Source: 2019-20 Periodic Labour Force Survey[59]

The data shows a clear need to balance mobilisation strategies to train more women and retain them in different sectors. It is imperative to undertake robust Skills Gap Analyses (SGAs) across states to distribute vocational training courses better. This will show which sectors require the establishment of specific training centres with regards to existing employment opportunities. The SGA reports must provide statistics regarding human resource requirements across various employment sectors and also reveal how many skilled beneficiaries (both male and female) have been employed and absorbed within these sectors. Volatility in the economy is reflected in the domestic labour market; therefore, the changes in jobs shown through the SGAs and the absorption capacity of these sectors need to be reflected in the courses offered.

Furthermore, a gendered and disaggregated study needs to be done to assess which sectors are averse to hiring a particular gender so that policymaking can be adapted to ensure appropriate and equitable employment generation tools in the area. Though the labour force participation in India’s urban workforce has risen slightly for women of all ages (from 15.9 percent in 2017-2018 to 18.5 percent in 2019-2020[60]), paid employment for women does not necessarily correlate with women’s freedom and agency, especially when an increasing workforce might still be constrained within a narrow scope of what constitute ‘feminine’ jobs, like care work. Despite the predicted growth in jobs for women,[61] many women workers are crowded into a small number of ‘female occupations,’ which can drive wages down.[62] The quality of the gained jobs must be scrutinised; these jobs must not restrict women’s potential for upward mobility while increasing competition for low and unskilled jobs.

In India, more women receive vocational training in care-related work, but with a declining fertility rate (from 4.0 to 2.5 children per woman[63]) and improved life expectancy, men and women must be trained to support age-related disabilities as homecare workers, paramedics and nurses. This important policy shift will benefit employment in the care sector and the requirement of care by an ageing population. India spends less than one percent of GDP on care work infrastructure and services, including pre-primary education, maternity, disability and sickness benefits, and long-term care.[64] Investing more in and formalising the care sector will increase jobs for caregivers and provide quality care for receivers.

Role of Technology in Future Care Work

Introducing more technology into the world of care may prove counterproductive. A robotic, clinical, artificial machine will be incapable of replacing the human touch required to care for someone subjectively and impulsively. However, although care work may never fully be automated, technology can enhance the ease with which humans perform their care duties and quickly anticipate needs.

A slew of ‘platform’ technologies has emerged to help connect care workers to care consumers, with specific criteria to provide the perfect match. For instance, Care.com, a platform with 32.9 million members across 20 countries, helps people find temporary, qualified care through a mobile app.[65] For caregivers, this works similar to an Uber for drivers—a platform to find customers, jobs, and incentives. Care receivers can sift through various resumes to find the best fit and seamlessly connect, book, and pay. Portea, with operations in 25 Indian cities and Malaysia, provides a similar marketplace for in-home healthcare services, including doctor consultations, physiotherapy, postnatal care, nursing, eldercare, and lab tests.[66]

In the UK, Australia, Canada, the US and New Zealand, the emergence of digital platforms coincides with a move to reduce the state’s role in the provision of care and encourage the growth of private (for‐profit and not‐for‐profit) services.[67] While these platforms may help match supply with demand and boost employment, issues of accessibility may reduce opportunities for the poor. The form and content of the platform may limit access for specific groups (for instance, those with low digital literacy or lacking the social skills necessary to negotiate care). These platforms may provide opportunities for more part-time work as independent contractors for already full-time workers. The progressive nature of the platform economy can destigmatise the otherwise ‘lowbrow’ nature of such work, and is therefore increasingly being taken up by young and highly educated platform users.[68]

Artificial intelligence (AI) can be used to navigate routine care for patients and the elderly by monitoring a person’s care requirements and activity and generating reminders and steps to take that need not involve constant human presence. Such sensors and monitors are crucial in times of social distancing. Tele-healthcare and virtual healthcare have amplified across the world during the pandemic. Investment in AI telehealth support within homes can significantly reduce the burden on the healthcare workforce during crises, with a guaranteed home visit for emergency situations.

Technology can be used to fulfil care needs through the regulation and control of physical space to reconcile with the issues of access, affordability and digital literacy and provide care without the sensory experience of human interaction within the home.[69] For instance, in home automation packages, a light path comes on when someone steps out of bed for night visibility and to reduce the likelihood of falls, environmental sensors can adjust heating, ventilation and air conditioning systems after detecting the human presence (and settings can be adjusted according to preferences).[70]

Automation in eldercare is rapidly growing in ageing nations like Japan, which is facing a simultaneous shortage of care workers, with robots engaged in delivering such care. However, constant human oversight is needed even in such cases so that the care recipient does not feel abandoned. Furthermore, care professionals should not have to tackle the added burden of managing trauma from an adverse experience with automated care.

Countering Disruptions to the Care Economy

Health crises like COVID-19 disrupt the care economy by causing job losses for caregivers and burdens women with unpaid care work. Interventions like technology to reduce the double burden of work, parental leave, and providing care facilities at work are some ways through which these disruptions can be mitigated, based on a country’s specific socio-economic and cultural context.

Several companies have created policies to support their employees during the pandemic. In India, Tata Steel tweaked its leave policy to include a “special leave”[71] for employees that needed to self-quarantine based on perceived exposure, while RPG Enterprises created an “exceptional leave”[72] policy with full pay for such instances. Twitter announced that all employees, including hourly workers, will receive reimbursement toward their home office set-up expenses.[73] None of these policies account for reduced hours of work due to attending to increased domestic requirements.

Germany could mitigate the effect of the pandemic on their workforce because the country runs a ‘short time work’ scheme in which firms experiencing economic difficulties can temporarily reduce the employees’ hours of work, with the State compensating for the lost hours.[74] This would mean that men and women who have to attend to domestic needs can be compensated for the lost work hours during the pandemic.

It is also important to consider including paid leave policies specifically for care-related activities during a crisis to mitigate the much larger economic fallout of women leaving the workforce.

To fully gauge the extent of damage done to the care industry, it must be considered as a distinct sector and included in country-wide labour force surveys. In India, most women are in home-based work and self-employment for women is also high, which means they will not be able to avail any employee pandemic benefits given by companies. Among female workers, informal workers accounted for 54.8 percent of the workforce.[75] Therefore, while companies categorically need to revamp their leave structures and employee benefit structures to account for disruptions caused by pandemics, governments must ensure that informal care workers that are not protected by these measures are not adversely affected by the pandemic’s damage to the economy.

Even if individuals are engaged in salaried labour, they do not fall into a formal employment structure unless the requisite employee benefits and contractual arrangements are attached. In India, more women work without these employee benefits than men. In India, in 2019-2020, among regular wage/salaried employees in the non-agriculture sector, 54.2 percent of workers were not eligible for any social security (up from 49.6 percent in 2017-2018). Of the regular wage earners, 53.6 percent of males are not eligible for social security compared to 56 percent of females. Among these regular wage workers, 68.1 percent of males did not have a job contract, compared to 65 percent of females. Moreover, 53.1 percent of the same regular wage male workers were not eligible for paid leave, compared to 49.8 percent of females.[76] With this overwhelming proportion of the workforce already facing a lack of job security and employment benefits, governments must strongly consider including pandemic-related clauses into social protection schemes.

While companies and government can work on contractual and social protection schemes, COVID-19 relief packages must account for the loss of employment due to closures of care facilities and decreased enrolment. Several countries have taken measures to facilitate a minimum level of childcare provision while day-care centres are closed. For example, Austria, France, Germany, and the Netherlands are providing emergency childcare services for essential workers by keeping some facilities open. Others have introduced childcare vouchers for health sector workers (for instance, Italy) or increased child allowances to acknowledge the shift from centre to home-based care (such as Poland and South Korea).[77] In addition, in anticipation of a potential third wave of COVID-19 (predicted to target the younger demographic), Maharashtra has created paediatric wards and creches for the children of patients.[78] A network of such care facilities will revive the slump in care work induced by work and school closures whilst providing adequate services to patients.

In India, the 2017 amendment to the 1961 Maternity Benefit Act seeks to promote women’s participation in the workforce by providing beneficial entitlements to female employees, like increasing maternity leave from 12 weeks to 26 weeks and ensuring that every establishment with over 50 employees has a crèche service.[79] The law was designed to ensure women’s participation is not hindered due to childbearing duties. Still, there must be laws to protect women from wage calculations of hiring for so-called ‘lost experience’ due to childbearing and infrastructural costs.

Sweden, for instance, has a parental leave law that gives both parents paid leave to care for children.[80] Such measures will eventually lead to egalitarian wages as the lost experience accrues for both parents, with research showing that “lower earnings following parental leave are well-documented across countries for women as well as for men.”[81]

Government initiatives can help ease companies into providing such benefits. For instance, in Lithuania, maternity and paternity leave is paid for by the government, while companies focus on granting leave and ensuring smooth reabsorption of the employee post the leave period. Such assistance from the government is beneficial as it helps prevent hidden hiring biases.

Skilling to increase digital literacy, familiarity with emerging medical technology terminology, and equipment handling is essential for care workers to keep pace with advancements. For instance, a US survey of 400 nurses on the new healthcare information technology introduced during COVID-19 showed mixed attitudes. Technical support in data management, collection, and quick access increased the efficiency of quickly tracing records. However, results also showed that nurses felt receiving technical support was obstructing their work due to unfamiliarity with technological terminology.[82]

Technology can enhance care services in detection, monitoring and automated guidance but can never fully replace the ‘high touch’ requirement of care of human responses to needs. Thus, skilling for the future of work must also focus on helping care workers in lowering their burden of work; better connectivity between caregivers and receivers without exclusion (that can only be done if all care workers are provided with formal skills and qualifications); and redistributing skilling initiatives for care work so that any disruption to the sector does not affect only a certain portion of the population.

Conclusion

The pandemic has had a severe impact on working women, both in the paid formal and informal sectors. Disruptions in care work have reverberated across countries. Reskilling, upskilling, distributing care work and employment opportunities, along with formalised and contractual paid leave and paternal leave, are essential instruments to protect care workers. While there is potential for women’s employment as care workers and it is vital to provide them with the required skills, skilling alone cannot solve the ‘care penalty’ issue and the sector’s informal status. State policies to regulate the sector and its workers are essential. Technological advancements will translate into increased demand for skilled labour and a concurrent improvement in working conditions and flexibility.

The care services remain a low-wage and long-hour space, perhaps due to its “high touch” nature that demands human presence.[83] Therefore, for both caregivers and receivers, it is crucial to invest in technology to support human care workers, initiate policies to care for patients’ families during health crises, and build an alternative and skilled care workforce that can withstand the debilitating impact of pandemics.

Endnotes

[1] Nancy Folbre, ‘Measuring Care: Gender, Empowerment, and the Care Economy,” Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 7 (1 July 2006): 186.

[2] Gaëlle Ferrant, Luca Maria Pesando and Keiko Nowacka, “Unpaid care work: the missing link in the analysis of gender gaps in labour outcomes”, OECD Development Center, December 2014.

[3] Ferrant, Pesando and Nowacka, “Unpaid care work: the missing link in the analysis of gender gaps in labour outcomes”

[4] International Labour Organisation. “The Care Economy,” https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/care-economy/lang–en/index.htm

[5] Paula England and Nancy Folbre, ‘The Cost of Caring’, The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 561 (1999): 45.

[6] Anu Madgavkar, James Manyika, Mekala Krishnan, Kweilin Ellingrud, Lareina Yee, Jonathan Woetzel, Michael Chui, Vivian Hunt, and Sruti Balakrishnan, “The future of women at work: Transitions in the age of automation,” McKinsey, June 4, 2019, https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/gender-equality/the-future-of-women-at-work-transitions-in-the-age-of-automation

[7] International Labour Organization, “Informal Economy Workers,” https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/wages/minimum-wages/beneficiaries/WCMS_436492/lang–en/index.htm

[8] “The future of women at work: Transitions in the age of automation”

[9] Ferrant, Pesando and Nowacka, “Unpaid care work: the missing link in the analysis of gender gaps in labour outcomes”

[10] Arundhati Chakravarty, “Explained: How to measure unpaid care work and address its inequalities,” The Indian Express, May 2, 2021.

[11] National Statistics Office, “Quarterly Bulletin Periodic Labour Force Survey July – September 2020”, Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, August 2, 2021.

[12] National Statistics Office, “Quarterly Bulletin Periodic Labour Force Survey January – March 2020”, Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation,

[13] Alex Thornton, “COVID-19: How women are bearing the burden of unpaid work” World Economic Forum, December 18, 2020.

[14] Sona Mitra, “Women and unpaid work in India: A macroeconomic overview,” IWWAGE, March 7, 2019.

[15] Julie MacLeavy, “Care work, gender inequality and technological advancement in the age of COVID-19”, Gender Work and Organisation (28:1), January 2021.

[16]Julia Kashen, “How COVID-19 Relief for the Care Economy Fell Short in 2020”, The Century Foundation, January 27, 2021.

[17] Bobo Diallo, Seemin Qayum, and Silke Staab, “COVID-19 and the care economy: Immediate action and structural transformation for a gender-responsive recovery”, UN Women (2020).

[18] Diallo et al, “COVID-19 and the care economy”

[19] Diallo et al, “COVID-19 and the care economy”

[20] Minouche Shafik, “What we owe each other,” International Monetary Fund, April 2021.

[21] Laura Turquet and Sandrine Koissy-Kpein, “Covid-19 and gender: What do we know; what do we need to know?”, UN Women, 13 April 2020.

[22] Lucie Prewitt, “Making Care Count,” Care Work and the Economy, May 24, 2021.

[23] Diallo et al, “COVID-19 and the care economy”

[24] Diallo et al, “COVID-19 and the care economy”

[25] William Wan, “Burned out by the Pandemic, 3 in 10 Health-Care Workers Consider Leaving the Profession,” The Washington Post, April 2, 2021.

[26] Francisco Sampaio, Carlos Sequeira, and Laetitia Teixeira, “Impact of COVID-19 Outbreak on Nurses’ Mental Health: A Prospective Cohort Study,” Environmental research (Elsevier Inc., March 2021).

[27] Thornton, “COVID-19: How women are bearing the burden of unpaid work”

[28] Kashen, “How COVID-19 Relief for the Care Economy Fell Short in 2020”

[29] UNESCO, “1.37 billion students now home as COVID-19 school closures expand, ministers scale up multimedia approaches to ensure learning continuity,” March 24, 2020.

[30] “Domestic Workers”, International Labour Organisation (ILO).

[31] ILO, “Domestic Workers

[32] ILO, “Domestic Workers”

[33] Premilla Nadasen, “Rethinking care: Arlie Hochschild and the global care chain,” Women’s Studies Quarterly 45 no.3/4 (2017).

[34] Lyn Ossome, “The care economy and the state in Africa’s Covid-19 responses”, Canadian Journal of Development Studies / Revue canadienne d’études du développement, 42:1-2 (2021).

[35] “COVID19 and gender monitor”, UN Women, June 2020.

[36] Campbell Robertson and Robert Gebeloff, “How Millions of Women Became the Most Essential Workers in America”, New York Times, April 19, 2020,

[37] “National Health Mission,” Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India.

[38] “Anganwadi Sevikas”, Ministry of Women and Child Development, Government of India, July 12, 2019.

[39] Aditi Ratho and Dharika Athray, “How are female essential workers faring amidst COVID19?” Observer Research Foundation, July 7, 2020.

[40] Nilanjana Bhowmick, “Millions of women volunteers form India’s frontline COVID response”, The National Geographic, June 1, 2020.

[41] “India: The Dual Battle Against Undernutrition and COVID-19 (Coronavirus)”, World Bank, April 27, 2020.

[42] Millions of women volunteers form India’s frontline COVID response”

[43] Abhishek Choudhari, “Asha workers protest for better wages”, The Times of India, May 11, 2021.

[44] Kamaldeep Singh Brar, “Covid management in Punjab villages: ASHA workers wait for pending incentives”, The Indian Express, May 11, 2021.

[45] “Delayed honorariums, no COVID-19 safety gear: ASHA workers in Kerala struggle,” The News Minute, May 6, 2021.

[46] “Anganwadi workers get online sessions on COVID-19 steps,” The Hindu, April 5, 2020.

[47] Kamaldeep Singh Brar, “Paid a pittance, ASHAs forced to buy or borrow smartphones for Covid survey,” The Indian Express, June 25, 2020.

[48] Bhowmick, “Millions of women volunteers form India’s frontline COVID response”

[49] Anu Madgavkar, James Manyika, Mekala Krishnan, Kweilin Ellingrud, Lareina Yee, Jonathan Woetzel, Michael Chui, Vivian Hunt, and Sruti Balakrishnan, “The future of women at work: Transitions in the age of automation,” McKinsey, June 4, 2019,

[50] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Fastest Growing Occupations : Occupational Outlook Handbook,” April 9, 2021.

[51] Lerato Shai, “Public Employment Programmes in the Care Economy: The Case of South Africa”, International Labour Organisation Working Paper 29 (April 2021).

[52] Lerato, “Public Employment Programmes in the Care Economy: The Case of South Africa”

[53] Lerato, “Public Employment Programmes in the Care Economy: The Case of South Africa”

[54] Lerato, “Public Employment Programmes in the Care Economy: The Case of South Africa”

[55] Lerato, “Public Employment Programmes in the Care Economy: The Case of South Africa”

[56] Lerato, “Public Employment Programmes in the Care Economy: The Case of South Africa”

[57]Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, “Annual Report, Periodic Labour Force Survey 2019-2020”, Government of India, (July 2021).

[58] Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (MOSPI), “Annual Report, Periodic Labour Force Survey 2019-2020”, Government of India, (July 2021).

[59] MOSPI, “Annual Report, Periodic Labour Force Survey 2019-2020”

[60] MOSPI, “Annual Report, Periodic Labour Force Survey 2019-2020”

[61] McKinsey, “The future of women at work: Transitions in the age of automation,”

[62] Bhalla, S. Surjit et al, “Labour Force Participation of Women in India: Some facts, some queries”

[63] Erin Fletcher, Rohini Pande, Charity Troyer Moore, “Women and Work in India: Descriptive Evidence and a Review of Potential Policies,” Harvard Kennedy School Faculty Research Series, (January 2018): 7

[64] Puja Mehra, “India’s Economy needs a big dose of health spending,” LiveMint, April 8, 2020.

[65] “Company Overview”, Care.com.

[66]“Roundup: 10 Indian Healthcare Startups You Should Know About”, Gadgets 360, February 1, 2016.

[67]MacLeavy, “Care work, gender inequality and technological advancement in the age of COVID-19”

[68]MacLeavy, “Care work, gender inequality and technological advancement in the age of COVID-19”

[69]MacLeavy, “Care work, gender inequality and technological advancement in the age of COVID-19”

[70] MacLeavy, “Care work, gender inequality and technological advancement in the age of COVID-19”

[71] Rica Bhattacharya, “Coronavirus: ‘Special leave’ to ensure isolation doesn’t hit pay”, The Economic Times, March 18, 2020.

[72] Bhattacharya, “Coronavirus: ‘Special leave’ to ensure isolation doesn’t hit pay”

[73] “Covid-19 scare: Cautious India Inc asks staff to work from home”, The Economic Times, March 13, 2020.

[74] European observatory of working life, “Short time work,” Eurofound.

[75] “Annual Report, Periodic Labour Force Survey 2017-2018”

[76] Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, “Annual Report, Periodic Labour Force Survey 2019-2020”, Government of India, (July 2021).

[77] International Labour Organisation, “Women health workers: Working relentlessly in hospitals and at home”, April 7, 2020.

[78] “Pediatric Wards, Creche Network for Parents in Covid Care: Maharashtra Govt Braces for Third Wave”, News18, May 3, 2021.

[79] Jessamine Mathew, “How can the Maternity Benefit Act Increase Female Workforce Participation?”, Economic and Political Weekly, 54 no. 22, (June 2019).

[80] Helen Eriksson, “Fathers and Mothers Taking Leave from Paid Work to Take Care of a Child: Economic Considerations and Occupational Conditions of Work”, Stockholm Research Reports in Demography, Stockholm University Department of Sociology (2018): 5.

[81] Eriksson, “Fathers and Mothers Taking Leave from Paid Work to Take Care of a Child: Economic Considerations and Occupational Conditions of Work”

[82] Aditi Ratho, “You’re on Mute” – Covid19, Technology-dependence, and Stress in Workers”, Observer Research Foundation, September 24, 2020.

[83] MacLeavy, “Care work, gender inequality and technological advancement in the age of COVID-19”

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Aditi Ratho was an Associate Fellow at ORFs Mumbai centre. She worked on the broad themes like inclusive development gender issues and urbanisation.

Read More +