Russia-India-China

The Russia-India-China triangle concept has Russian provenance, in an idea that the then Russian Foreign Minister Evgenii Primakov pitched in New Delhi in December 1998. In Primakov’s conception, strategic partnerships between Moscow, New Delhi, and Beijing would become one key way by which American power in the unipolar moment could be balanced.[16] The RIC, as this triangular relationship came to be known, forms the nucleus of political BRICS.[17]

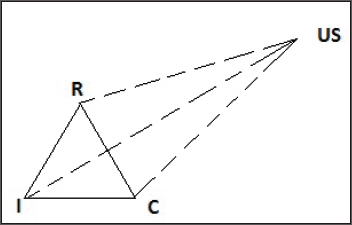

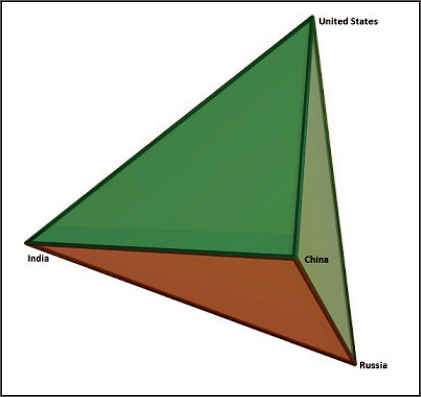

But scholars have argued, and with good reasons, that this idea was doomed to fail right from the very beginning.[18] BRICS – and RIC as a subset – continues to falter for two key reasons. One, because of increasing friction between China and India[19] and, two, for the perception among many in New Delhi’s strategic community that India and China’s cooperation in BRICS and other global-governance platforms has not translated into greater accommodation of Indian interests by China. The essence of the empirical argument that Pant advanced against RIC was that the bilateral relationships between the three countries were much less than what all three individually had with the United States.[20] Conceptually, if a triangle (RIC) is to ‘balance’ a point (US), which was Primakov’s vision, then one has to consider all other triangles in the question which have the US as one of the vertices. In other words, the great-powers tetrahedron will have to be considered (Figure 2 should help visualise this situation).

Figure 2

To fit the historical trajectory of Russia-India-China triangular behaviour into Dittmer’s terminology: up and until the end of the Cold War, it formed a ‘stable marriage’ in that the USSR and India had a cordial relationship, and each had reasons for animosity towards China. Primakov wanted a ‘ménage à trois’ of the three powers. At present, it is difficult to neatly categorise the RIC triangle using Dittmer’s terminology.

US-India-China

If the RIC was a classic example of a Mackinderian construct – involving land powers in the heartland and the inner crescent – the US-India-China triangle is a textbook Mahanian story. It was explored as such by Raja Mohan in a recent book.[21] The gist of Mohan’s story is a classic security dilemma that is likely to play out between China and India when it comes to the domination of the Indo-Pacific. As China thrusts outward, ostensibly for commercial reasons, its access to – and control of parts of –the waters of the Indo-Pacific would become a key priority. India too lays claim on large parts of the Indo-Pacific. A security dilemma would thus be born. In Mohan’s narrative, like the gods of the story of the Hindu myth of a “Samudra Manthan” (literally, ‘the churning of the ocean’), the US will largely determine the balance of power in the region.

As such, a strategic triangle (involving the three countries) is to be expected. With the US-India relationship on an upturn, especially in the form of military cooperation, since the beginning of the 21st century, and the India-China relationship significantly worsening over the last year, the main story to watch out for with the new administration in the United States is how Donald Trump handles China – and visualises India’s role as a leading offshore balancer. Since assuming the presidency in January 2017, Trump has reversed his position on China and, at the same time, has failed to articulate a clear South Asia policy and India’s role in it. But Mahanian geopolitics in the Indo-Pacific would suggest that the US-India-China triangle would that be of a ‘stable marriage’ between the US and India with China as the third party, to use Dittmer’s terminology.

US-China-Russia

The most examined strategic triangle in IR theory, that led to the rapprochement between the US and China in 1972, is the US-China-USSR triangle. Richard Nixon, upon being elected to the White House in 1969, quickly noted the worsening relationship between the USSR and China, a nadir of which was the Usuri border clashes of 1969. By bringing China to the US side, Nixon wanted to tilt the balance of power away from the USSR as well as—and this is underappreciated— to gain a favourable hand when it came to resolving the quagmire in Vietnam.[22] Kissinger noted in his memoirs: “The buildup of Soviet divisions on the border [in 1969] implied that a Soviet Union faced with tensions on two fronts […] will be ready to explore a political solutions with America, especially if we succeeded in the opening to China […]”[23]

Triangular patterned behaviour is not static and changes with time. Dittmer has noted that between 1949 and 1960, the USSR and China was in a ‘stable marriage’ with the US as the third party.[24] However, between 1970 and 1978, the triangular relationship became a ‘romantic triangle’ with the US as the ‘pivot’ player and USSR and China as the ‘wing’ players following the Nixon-Kissinger triangular diplomacy of 1969-1972.[25]

Many have read shades of Richard Nixon in Donald Trump – and this has not always meant a compliment.[26] However, should Trump engineer a ‘reset’ of the US-Russia relationship, there is another potential strategic triangle in the making, this time interchanging the roles of Russia and China. The Russia-China relationship is, on the surface, friendly and cooperative. It has also been termed as an ‘axis of convenience’.[27] The United States looms large over this relationship. Dittmer notes that the unspoken driver of Russia-China relationship is “its greater geopolitical leverage vis-à-vis the American superpower.”[28]

In a nod to Brzezinski’s ‘Grand Chessboard,’ Lo noted (in 2008, before Crimea, but also before Trump) that “the perfect scenario is for the United States and China to treat Russia as an essential partner in countering the other other’s hegemonic ambitions.”[29] Many suspected that Trump would warm up to Russia upon assuming office, given Vladimir Putin’s support for his presidency. However, this has not turned out to be the case. Trump has described the US-Russia relationship to be at “an all-time low.”[30] In particular, Trump’s renewed commitment to NATO and his decision to militarily retaliate against the Syrian regime’s decision to use chemical weapons against civilians make the possibility of a reset of Russia-America relationship in the near future remote.

US-India-Russia

Soon after Trump’s election, the Indian foreign secretary noted that given India’s ties with both the United States and Russia, “an improvement in US-Russia ties is therefore not against Indian interests.”[31] Implicit in this statement was the hope that the US-Russia-India strategic triangle would follow a ‘ménage à trois pattern’ from a ‘romantic triangle’ pattern (in Dittmer’s terminology). Indeed, in India’s quest for a multipolar world it has engaged with both countries, even when the relationship between Russia and the west was far from amicable. For example, India refused to ostracise Putin after the Crimea invasion in 2014 and protested (along with the other BRICS) the Australian suggestion that Russia be suspended from the G20 because of its intransigence.[32] India has also (implictly) backed the Russian position on Syria[33] while continuing to deepen its military cooperation with the United States. However, Moscow remains India’s largest supplier of weapons, and between 2012 and 2016, Russia accounted for 68 percent of India’s arms imports.[34]

From Moscow’s point of view, as Russia pivots to Asia, it should engage India to the extent that this pivot stops being just a “pivot to China.”[35] But the Russia-India relationship remains quite lopsided with the economic leg becoming quickly irrelevant: In 2016, one percent of India’s total trade was with Russia; India accounted for 1.2% of Russia’s total trade.[36] Compare this with the US$ 114.8-billion bilateral trade in goods and services between the United States and India in the same year.[37] Even in the military-sales part of the relationship, cost overruns on Russian acquisitions has dampened India’s enthusiasm for acquiring high-end Russian platforms. The Russian decision to hold a joint military exercise with Pakistan in 2016 – and the possibility of a nascent ‘China-Pakistan-Russia’[38]axis emerging – stands to significantly add to the stress in the India-Russia relationship. If these patterns continue to strengthen, in the US-India-Russia triangular relationship, the US will have much more to offer to India as well as Russia (especially if a US-Russia reset relationship does happen) than what they offer each other. The key variable that would determine the pattern of the triangle would be China.

About the author

Abhijnan Rej is a Fellow at the Observer Research Foundation, New Delhi. His current research interests include Indian foreign policy and grand strategy, international security, and Asian geopolitics.

[1]“Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov’s address and answers to questions at the 53rd Munich Security Conference, Munich, February 18, 2017,” The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation, http://www.mid.ru/en/web/guest/meropriyatiya_s_uchastiem_ministra

/-/asset_publisher/xK1BhB2bUjd3/content/id/2648249. For a scholarly analysis of this concept, see Oliver Stuenkel, Post–Western World: How Emerging Powers Are Remaking Global Order (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2016).

[2]For a discussion of the shared assumptions as well as key differences between structural realism and game theory, see Robert Jervis, “Realism, Game Theory and Cooperation,” World Politics 40 (1988).

[3]Henry Kissinger, On China (Penguin Books, 2012 reprint), 115.

[4]Henry Kissinger, Diplomacy (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1994 ), 720.

[5]Kissinger, White House Years (Boston: Little Brown, 1979), 165.

[6]Lowell Dittmer, “The Strategic Triangle: An Elementary Game-Theoretical Analysis,” World Politics 33 (1981): 485-515.

[7]Dittmer, “The Strategic Triangle,” 485.

[8]Dittmer, “The Strategic Triangle,” 487.

[9]Ibid.

[10]Dittmer, “The Strategic Triangle,” 489.

[11]Quotation marks around triangles are indeed needed since not every triangular relationship is a strategic triangle in the sense of Kissinger.

[12]“The World in 2050,” PricewaterhouseCoopers, accessed February 22, 2017, http://www.pwc.com/gx/en/issues/economy/the-world-in-2050.html.

[13]For a discussion of the notion of a hybrid state, see Richard Rosencrance, The Rise of the Trading State: Commerce and Conquest in the Modern World (New York: Basic Books, 1986).

[14]H.J. Mackinder, “The geographical pivot of history,” The Geographical Journal 23 (1904): 441-444.

[15]For a relatively contemporary account of the importance of Eurasia in geostrategy, see Zbignew Brzezinski, The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy and Its Geostrategic Imperatives (New York: Basic Books, 1997).

[16]Iwashita Akhiro, “Primakov Redux? Russia and the “Strategic Triangles in Asia,” 21st Century COE Program Slavic Eurasian Studies 16 (2009), 167, http://src-home.slav.hokudai.ac.jp/coe21/publish/no16_1_ses/09_iwashita.pdf

[17]C. Raja Mohan, “BRICS Summit: Modi, Xi, Putin,” The Indian Express, October 15, 2016,http://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/brics-brazil-russia-india-china-south-africa-vladimir-putin-xi-jinping-narendra-modi-barack-obama-nuclear-suppliers-group-nsg-3083150/.

[18]See, for example, Harsh V. Pant, “The Moscow-Beijing-Delhi ‘Strategic Triangle’: An Idea Whose Time May Never Come,” Security Dialogue 35 (2004): 311-328.

[19]The 2017 RIC Foreign Ministers’ trilateral in New Delhi was cancelled when the Chinese foreign minister refused to attend the same. See “Dalai Lama’s Arunachal visit: Beijing not to attend Russia-India-China foreign ministers’ meet in Delhi,” Financial Express, May 5, 2017, http://www.financialexpress.com/india-news/dalai-lamas-arunachal-visit-beijing-not-to-attend-russia-india-china-foreign-ministers-meet-in-delhi/654800/.

[20]Harsh V. Pant, “The Moscow-Beijing-Delhi ‘Strategic Triangle,” 311.

[21]C. Raja Mohan, SamudraManthan: Sino-Indian Rivalry in the Indo-Pacific (Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2012). For an illuminating review of this book, see K.P. Fabian, “Strategic Triangle,” Frontline, July 26, 2013.

[22]For an account of the considerations, see Walter Isaacson, Kissinger: A Biography (New York: Simon and Schuster: 2005). Also see Kissinger, White House Years.

[23]Kissinger, Diplomacy, 713.

[24] Dittmer, “The Strategic Triangle,” 491.

[25]Dittmer, “The Strategic Triangle,” 499.

[26]David Kaiser, “You Can Compare President Trump to Richard Nixon, But Times Have Changed,” Time, March 9, 2017, http://time.com/4697223/trump-nixon-comparisons/.

[27]Bobo Lo, Axis of Convenience: Moscow, Beijing, and the New Geopolitics (London/Washington, DC: Chatham House/Brookings Institution Press, 2008).

[28] Lowell Dittmer, “The Sino-Russian Strategic Partnership: The End of Rivalry,” in Asian Rivalries: Conflict, Escalation and Limitations on Two-Level Games, Sumit Ganguly and William R. Thompson, eds. (Stanford University Press, 2011), 133.

[29]Lo, Axis of Convenience, 165.

[30] Julian Borger and Alec Luhn, “Donald Trump says US relations with Russia ‘may be at all-time low’,” Guardian, April 13, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2017/apr/12/us-russia-relations-tillerson-moscow-press-conference.

[31]Archis Mohan, “Why did Trump call India ahead of Moscow? It’s about domestic US politics,” Business Standard, January 25, 2017, http://www.business-standard.com/article/current-affairs/why-did-trump-call-india-ahead-of-moscow-it-s-all-about-us-politics-117012500477_1.html.

[32] “BRICS countries oppose ban on Vladimir Putin attending G-20 Summit,” LiveMint, March 24, 2014, http://www.livemint.com/Politics/T650zeLZqDbUJl5NhxgQ3M/BRICS-countries-oppose-ban-on-Vladimir-Putin-attending-G20.html.

[33]Viju Cherian, “Syria happy with India’s ‘balanced’ stand on crisis: Riad Abbas, Syrian ambassador to India,” Hindustan Times, April 14, 2017, http://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/syria-happy-with-india-s-balanced-stand-on-crisis-riad-abbas-syrian-ambassador-to-india/story-wAiqz0h77zFmnzec0IqDNP.html.

[34] “Russia still India’s largest defence partner,” Economic Times, February 22, 2017, http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/defence/russia-still-indias-largest-defence-partner/articleshow/57290157.cms.

[35]Dmitri Trenin, “Pressing Need to Tap Potential of Bilateral Ties,” in A New Era: India-Russia Ties in the 21st Century (Moscow/New Delhi: Russia Beyond the Headlines/Times Group, 2015), 15.

[36]Arun S., “Russia – a forgotten trade partner?,” Hindu, April 9, 2017, http://www.thehindu.com/business/Economy/russia-a-forgotten-trade-partner/article17898013.ece.

[37] “U.S.-India Bilateral Trade and Investment,” Office of the United States Trade Representative, March 22, 2017, https://ustr.gov/countries-regions/south-central-asia/india.

[38] Joy Mitra, “Russia, China and Pakistan: An Emerging New Axis?,” The Diplomat, August 18, 2015, http://thediplomat.com/2015/08/russia-china-and-pakistan-an-emerging-new-axis/.

PDF Download

PDF Download

PREV

PREV