Introduction

Bhutan is a small landlocked country located between two of Asia’s biggest economies—India and China. With India, it borders Sikkim to the west, West Bengal and Assam to the south, and Arunachal Pradesh to the east; and with China, it is a neighbour to the Tibetan Autonomous Region to the north. Bhutan has maintained a special relationship with India since the signing of the Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation in 1949. India views Bhutan as a “buffer” state against China’s aggression and military adventures. Its adjacent location to the Siliguri Corridor or “chicken’s neck”—which connects India to the rest of the North East Region (NER)—has only reinforced and strengthened these anxieties over a Chinese invasion and a potential isolation of the NER from the rest of the mainland. Bhutan is also the only South Asian country that has consistently respected India’s security concerns and has resisted joining either projects linking China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in the region or other forms of assistance such as grants and loans. Therefore, India’s policy has also tried to accommodate Bhutan’s interests, in order to sustain their economic integration and pursuit of common security goals.

China, meanwhile, has employed both persuasion and coercion to solve its territorial disputes with Bhutan. Some of these “rewards” include recognising Bhutan as a sovereign state, and offering it grants and new trade routes.[1] It has so far largely failed, however, to convince Bhutan to come to its fold; China is therefore employing more coercive strategies to achieve its objectives with Bhutan.

There are Chinese scholars who are of the view that China’s territorial differences with Bhutan are insignificant [2]—meaning that China’s policy and territorial disputes with Bhutan are largely defined by its external and internal calculations that are not necessarily linked to Bhutan. Internally, China remains anxious of the Tibet question, and a “friendly” or even “neutral” Bhutan is seen as a means to legitimise China’s control in Tibet, which shares racial, cultural, and ethnic similarities with Bhutan.[3] This is vital, especially at a time when Chinese President Xi Jinping is aiming for internal cohesion and would like to eliminate any separatist threats emanating from Tibet.[4]

Externally, given unresolved border issues and absent diplomatic relations with China, Bhutan is posing challenges to China’s global aspirations. China also perceives Bhutan’s China policy as a by-product of India’s dominance and control.[5] It is therefore keen for Bhutan to shed the last signs of India’s historical hegemony in the region.[6] Having diplomatic and economic presence in Bhutan and solving its territorial disputes can also help China expand to new markets and improve its offensive positioning against India vis-à-vis the Siliguri Corridor.[7] For this reason, Bhutan’s bilateral relationship with India and China is complex, influenced as it is by the broader India-China relationship. Some Bhutanese scholars perceive China’s acts of intimidation as a means to punish Bhutan for aligning with India.[8]

To be sure, the unresolved border disputes and persistent intimidating tactics continue to provoke anxiety in Bhutan. Yet the country is keen to not compromise on its territories nor hurt the security interests of India. Indeed, Bhutan remains one of India’s most reliable and trusted allies. This is not to say that Bhutan is not experiencing domestic and external pressures that are challenging its security calculations. This paper tracks the economic and demographic shifts in Bhutan, the impacts of globalisation and its own democratic transition, as well as of China’s rise and other geopolitical patterns of the recent years. The first section describes Bhutan’s complex relationship with India and China, and the second section assesses the key drivers of Bhutan’s foreign policy. The succeeding section then highlights the most crucial internal and external challenges to Bhutan. The paper closes with an exploration of the implications of these pressures for Bhutan’s foreign policy, specifically with respect to India and China.

Bhutan’s Foreign Relations: India, China, and ‘the Rest’

India and Bhutan’s relationship is shaped by their Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation of 1949. The agreement permitted India to “guide” the foreign policy of Bhutan while assuring the latter of its sovereignty.[9] Nonetheless, Bhutan continued practicing its self-declared isolationist policy during that time. The treaty also entrenched the concept of “common security” in their relationship.[10] There is also a possibility of a security arrangement between both the countries—whose particulars are yet to be made public.[11]

Bhutan’s security calculations, however, rapidly changed as China invaded Tibet in 1949. China’s invasion was based on its historical claim of having ruled Tibet till 1913.[12] Surprisingly, when Mao Zedong re-emphasised the need to annex Tibet in 1930, he also asserted that Ladakh, Nepal, Sikkim, Bhutan, and Arunachal Pradesh were part of Tibet.[13] These claims threatened Bhutan, as the former shared close historical and cultural ties with Tibet, and also practiced mutual sovereignty and grazing lands over certain territories; Bhutan also had a complicated tributary practice with Tibet.[14] China’s new maps of 1954 and 1958, and its occupation of Bhutan’s 300 square miles in 1958, further fuelled the apprehensions of a Chinese invasion.[15]

With then Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru’s visit in 1958, Bhutan shunned its isolation policy and began to look south. Bhutan saw the opportunity to ensure its sovereignty by seeking security and socio-economic assistance from India while gradually diversifying its relations with other countries.[16] It was further compelled to move closer to India, as it ceased all its diplomatic and economic ties with Lhasa to retaliate against China’s annexation of eight Bhutanese enclaves in Tibet in 1959.[17]

This commenced a new phase in the donor-recipient relationship between India and Bhutan. Bhutan became a beneficiary of India’s investments and social and physical infrastructure projects.[18] These projects included the construction of roads, schools, and hospitals. Indians were also recruited to mentor Bhutanese youth in the aforementioned sectors.[19],[20]

In 1960, China released another map which again incorporated certain Bhutanese territories.[21] This intimidated Bhutan and reinforced threats of a potential Chinese invasion. In 1961, as per Bhutan’s request, India deployed its Military Training Team (IMTRAT) in Bhutan to train the Bhutanese army,[a],[22] and the Eastern Command and Eastern Air Command of the Indian Army integrated the protection of Bhutan in their respective roles.[23] In the same year, India began funding Bhutan’s five-year plans[b] (see Table 2). The Indian Border Road Organisation also embarked on project Dantak to construct infrastructure such as motorable roads,[c] schools and colleges, airfields, and hospitals.[24],[25]

In 1962, China published five additional maps claiming several Bhutanese territories as theirs.[26] Compounded by India’s defeat in the 1962 war, this triggered a domestic debate on “equal friendship” in some sections of Bhutan.[27] However, discarding the idea of equal friendship, Bhutan engaged in a two-phased policy: It continued to maintain ties with India as they shared mutual interests in deterring Chinese aggression; and, to ensure its sovereignty while diversifying sources of foreign aid, Bhutan expedited its outreach to the outside world.

During this time, Bhutan and India demarcated most of their border points.[28] Bhutan became a member of various multilateral organisations, established a UN mission in New York, and recognised and signed a transit agreement with Bangladesh.[29]

By late-1970s, Bhutan supplemented this strategy by taking a more independent stand for itself. This was due to the anxiety triggered by India’s annexation of Sikkim in 1975, and a large intrusion of Tibetan herders in 1979.[30] The Bhutanese National Assembly thus emphasised a direct bilateral engagement and the need to have neutral relations with China, rather than asking India to negotiate or mediate on its behalf. This was a reasonable departure from the National Assembly’s 1978 resolution to avoid any kind of trade or diplomatic missions with China.[31] In the same year, Bhutan expressed its right to reject India’s foreign policy suggestions.[32] It did not vote with India in the United Nations on several occasions, though it remained sensitive to India’s interests. It also initiated its first-round expansion of diplomatic relations with other middle and small powers in Asia and Europe.[33]

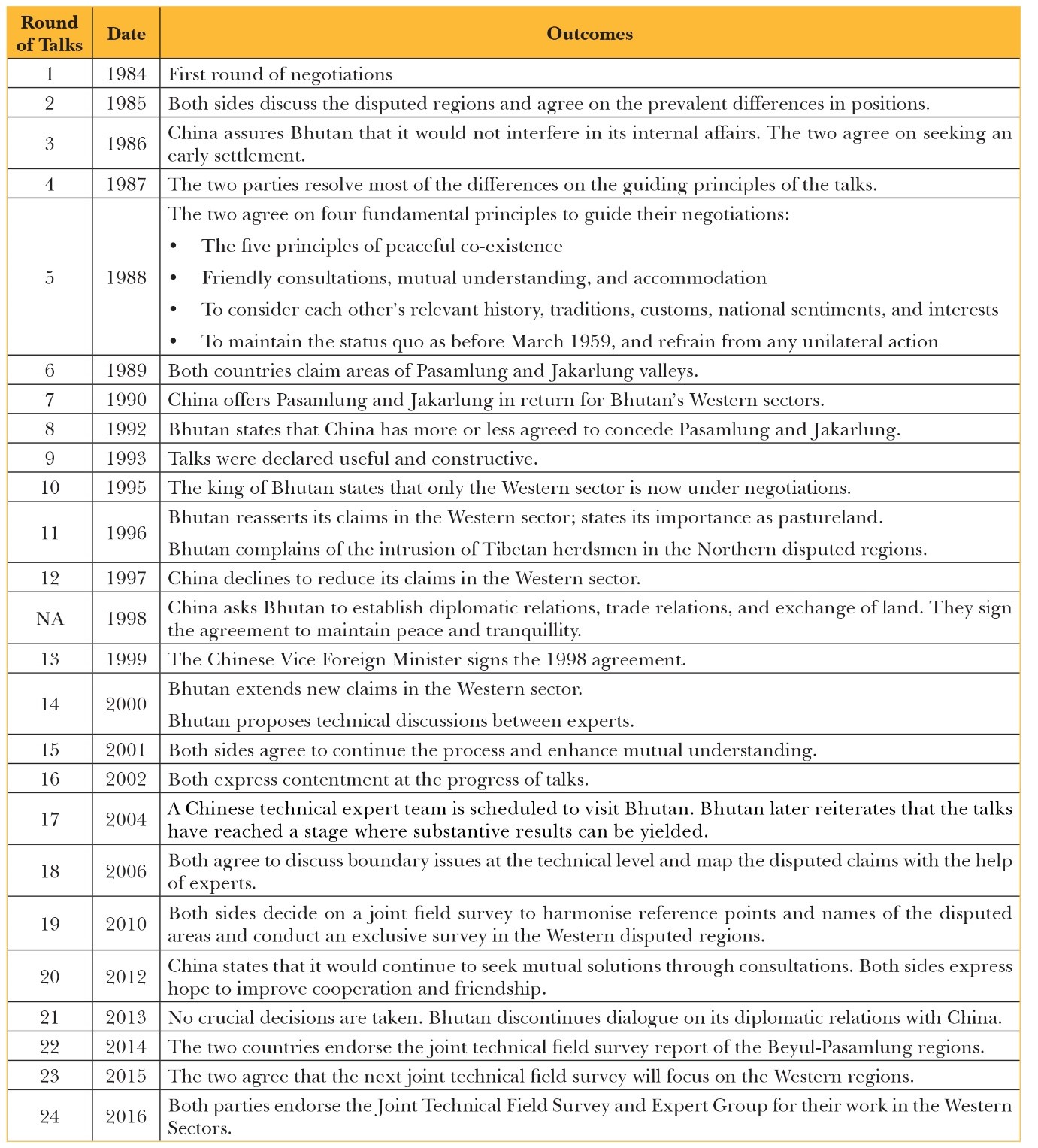

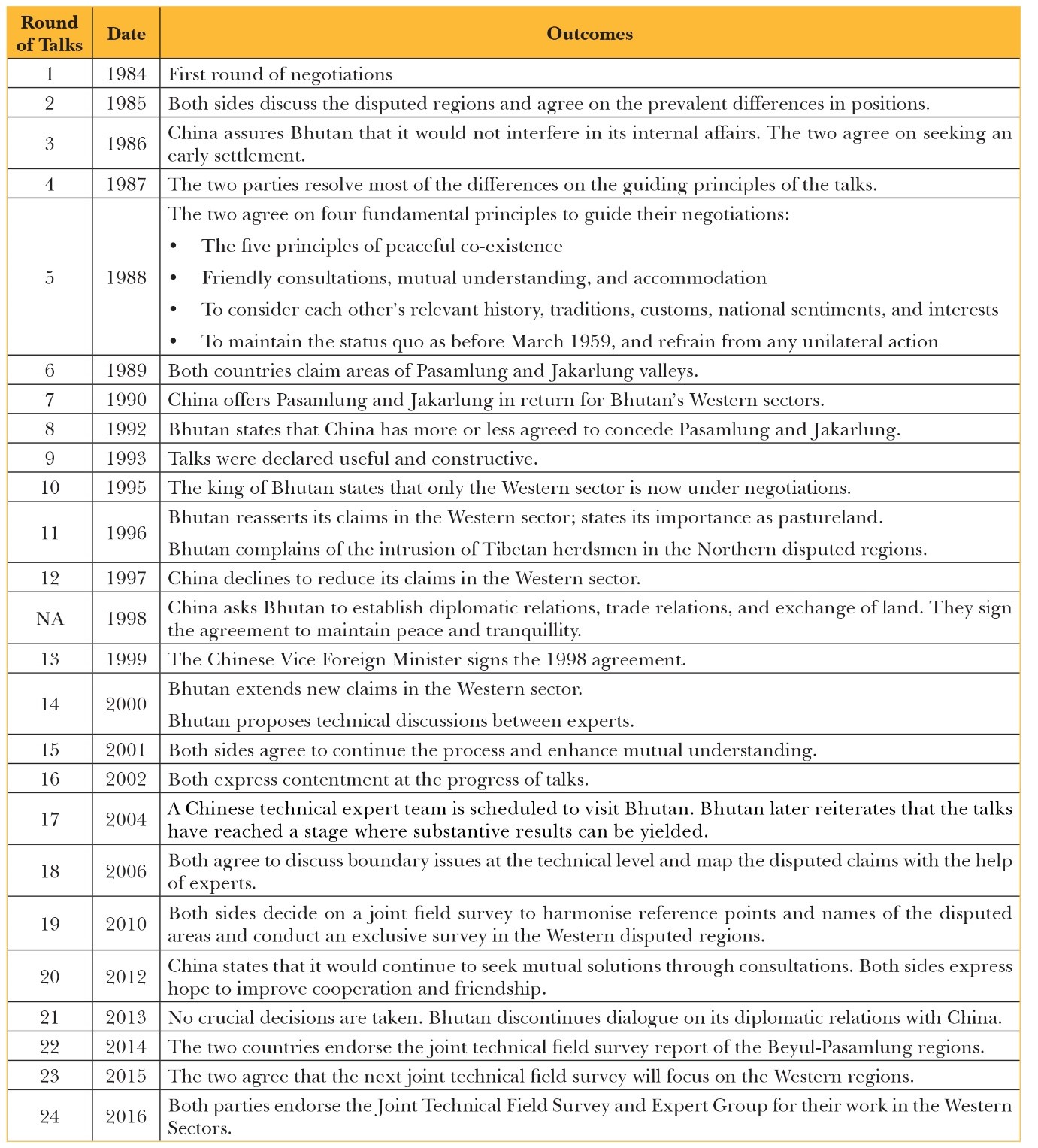

Bhutan began its first round of border negotiations with China in 1984 (see Table 1). During this “engagement phase”, i.e., from 1984-1996, Bhutan and China outlined their territorial claims,[34] which can be broadly classified into two sectors: In the North or Central Bhutan, the disputed areas are Pasamlung and Jakarlung valleys[d]—both culturally significant for Bhutan; and in the West, four regions are disputed, namely, Doklam, Dramana and Shakhatoe, Yak Chu and Charithang Chu valleys, and Sinchulungpa and the Langmarpo valley.[35] These regions are pasture-rich, and are strategically located in the Bhutan-India-China trijunction, precariously close to India’s chicken’s neck.

The following phase was the ‘redistribution phase’ that lasted till 2000.[36] During this period, China exerted pressure on Bhutan by encouraging Tibetan herders to settle and clash with the Bhutanese herders in the disputed regions of the North.[37],[38] Bhutan declined China’s earlier offer to surrender its claims in the North, if Bhutan gives up on the strategic regions of the West. Bhutan rejected the offer for nationalist and economic reasons, and India’s security concerns.[39] The negotiations ended in a stalemate, and an agreement in 1998 to maintain the status quo.

The third phase, i.e., the “normalisation phase”, began in 2000 when Bhutan extended its border claims and proposed more technical solutions to the disputes.[40] While both parties had intensified their negotiations, the impasse continued throughout this phase. China built pressure on Bhutan by moving Tibetan herdsmen, engaging in border intrusions, building roads, patrolling close to Bhutan, and constructing military camps—all of which were in violation of the 1998 agreement.

Table 1: Bhutan and China’s Talks and their Outcomes

Source: Author’s own, using various sources.[41]

In a parallel development, India and Bhutan had by now begun what they called “equal partnership”. By the 1980s, India’s assistance to Bhutan’s social and physical infrastructure, such as roads, education, and trade—had created sufficient backward linkages in Bhutan to develop hydropower projects.[42] Thus, starting from the 1980s, India had been making investments in Bhutan’s hydropower sector[e] and importing this hydropower electricity at reasonable rates. The two countries also made efforts to limit the spillover impacts of transnational terrorism. India clamped down on the Nepali militants operating from India’s NER and promoting secessionism in Bhutan, while the king of Bhutan himself led an offensive against the Indian North East militant camps in Bhutan in 2003.[43]

In 2007, India and Bhutan signed the ‘Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation’,[44] putting an end to India’s role of advising Bhutan in its foreign policy. However, the two agreed to cooperate on issues of national interest and continue working for their “common security”.[45],[46] With its newfound autonomy, Bhutan embarked on the second round of its diplomatic expansion, mainly intended to diversify and seek economic support and foreign investments. The beginning of the millennium witnessed a keen interest in Bhutan to promote economic growth and FDIs.[f],[47] By 2013, Bhutan had established relations with 53 countries.[48] More importantly, Bhutan attempted to establish diplomatic relations with China, serving two purposes: One, agreeing to China’s 1998 demands of establishing diplomatic ties and a subsequent end to the border disputes; and two, exploiting the economic benefits of China’s burgeoning economy.

However, Bhutan’s outreach to China was believed to reinforce India’s anxieties of China getting closer to the chicken’s neck, and India losing a ‘buffer state’ and its regional influence. As a result, India allegedly imposed a subsidy cut against Bhutan’s gas and kerosene imports, just before its elections in 2013. This served as one of the reasons for the change in the government, and reverted the succeeding government to a stalemate with China.[49]

Meanwhile, India has continued to be Bhutan’s largest economic and development partner. India has also enhanced the narrative of “equal partnership” by facilitating bilateral and sub-regional connectivity with Nepal and Bangladesh in recent years. Moreover, India and Bhutan are opening more trade routes to facilitate these economic interactions. For instance, in 2021 alone, India and Bhutan agreed to open seven new trade entry and exit points in addition to the 21 approved in 2016.[50] The potentially mutual benefits of this relationship was highlighted by Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi during his visit to Bhutan in 2014, when he first used the terms “B2B” (for “Bharat to Bhutan”) and “B4B” (Bharat for Bhutan and Bhutan for Bharat).

China, meanwhile, began its fourth phase of negotiations with Bhutan post-2010, which this paper calls the “enforcement phase”. In this phase, China is supplementing its earlier tactics with border laws and policies to build permanent settlements within undisputed territories of Bhutan. The aim is to use its material might to compel Bhutan to negotiate and end the dispute soon.

This enforcement phase is likely a result of both endogenous and exogenous developments in China. The primary driver is China’s decoupling from the US and India, and its intensification of efforts to rise to global leadership. Furthermore, it is trying to neutralise the potential challenges it could face from small and middle powers vis-à-vis other external powers or Tibet. China is also preparing for any unrest that may unfold in Tibet related to the issue of succession of the 14th Dalai Lama; it is concerned that countries like India, or those in the West, might lend their support to these protests.[51] This explains its accelerated efforts to neutralise Bhutan.

Second, this phase has largely been shaped by Xi Jinping’s focus on repopulating Tibetan borderlands and strengthening national security.[52] China continues to be anxious of Tibet, and is using its economic and military might to strengthen border security.[53] The 13th Five-Year Plan (2016-2020) intensified infrastructure development in the border villages and promoted resettlement on Tibetan borders based on the Chinese customary lines[54] that have not been officially demarcated with Bhutan.

China has thus started building permanent settlements, making intrusions, and asserting new claims in Bhutan.[55] Among the latter are the claims being made on the Sakteng wildlife sanctuary of Eastern Bhutan. These activities violate the 1998 agreement and are pressuring Bhutan to break the stalemate and end its disputes with China. In 2021, Bhutan and China signed an MoU to expedite negotiations and solve the border disputes.[56] The English-language Chinese media were quick to declare this development a “deadlock breaker” which has distorted Indian influence and security calculations in the region and will hereafter redefine Bhutan-China relations.[57]

The Fundamentals of Bhutan’s Foreign Policy

The following paragraphs describe the pillars of Bhutan’s foreign policy.

Territorial integrity and sovereignty

Located between two mighty neighbours, Bhutan, given its small size, is constantly wary of being swallowed up by either of them. Since China’s invasion of Tibet, Bhutan has become extremely sensitive about its territorial integrity and sovereignty, and has made it a top priority. Though it is silent about the territories it has already lost in Tibet and Kula Kangri,[58] it is resisting any changes in its current borders. It has thus consistently attempted to resolve the border issue with China, be it through India till 1984, or through direct bilateral protests and negotiations thereafter.

Bhutan even agreed to step up bilateral talks with China when the latter refused to negotiate through India. Throughout 24 rounds of negotiations, Bhutan has been very defensive of its boundaries, despite China’s belligerence. The negotiations continue despite China having begun annexing some regions within Bhutan and resettling people there. Indeed, Bhutan extended its claims in the Western sector and exhorted China to be more generous during negotiations.[59]

This issue of sovereignty and external involvement has also restrained Bhutan from establishing formal diplomatic ties with any of the permanent members of the UN Security Council (or P-5 countries – US, Russia, China, UK and France). It is wary of losing its sovereignty and territorial integrity if it becomes a playground for the politics of the big powers.[60]

Balance of Threat

Bhutan’s relations with its neighbours is a product of a ‘Balance of Threat’ and not a ‘Balance of Power’.[g] American political scientist Stephen Walt argues that a state decides its alliances based on four factors: aggregate power;[h] geographical proximity; offensive power or capabilities; and the state’s intentions.[i], [61] Both India and China are adjacent to Bhutan and possess superior military power with offensive capabilities. However, Bhutan’s decision to align with India and not with China is based on the factor of intentions.

Though it signed its initial friendship treaty with India in 1949, Bhutan’s relations with India intensified only in the late 1950s, after China annexed Tibet and became territorially aggressive. Consistent intimidation by China and attempts to pressure Bhutan has driven the landlocked state to seek out India for economic and security shelter. This teaming up against China indicated that both the states had mutual interests in limiting Beijing’s aggressiveness and maintaining their territorial integrity. Bhutan continued to align with India despite the latter’s defeat in the 1962 war.

This ‘Balance of Threat’ has also compelled Bhutan to accommodate and respect Indian sensitivities, and vice-versa. Bhutan has never used the China card against India. It has led to Bhutan’s dependence on the Indian economy and development projects without any concerns of threat. Bhutan has chosen to remain sensitive to India’s concerns despite China’s economic and military superiority over India.

Self-interest

Despite its special friendship with India, Bhutan has often perceived the relationship through the lens of self-interest.[62] Broadly, Bhutan’s interests are twofold: protecting its territories, and becoming a self-reliant and self-sufficient economy.[63] Security concerns have often been predominant and have determined Bhutan’s economic calculations.[64]

Thus Bhutan has coordinated with—and even appeased—India on various occasions when costs of doing so were low and political and economic benefits were high. For instance, Bhutan’s policies vis-à-vis Pakistan or India’s northeast insurgents have largely accommodated Indian interests. Bhutan was even the first country to recognise Bangladesh.[65] But Bhutan has also been assertive and defensive when the political costs were high and self-interest was being threatened. This was seen after India’s annexation of Sikkim in 1975, or even in Bhutan’s insistence on renewing the 1949 agreement.

Bhutan’s China policy also reflects its self-interest. To protect its territories and ensure its survival, Bhutan has tried to maintain a neutral relationship with China, for instance, during the 1962 war. It began bilateral talks with China from 1984, in an effort to deter Chinese aggression (though formal diplomatic ties are yet to be established). It has maintained a strategic silence on many occasions on India-China differences. Most importantly, Bhutan has even acknowledged the ‘One China’ policy despite China’s coercive tactics.[j] It has stayed silent on the Tibetan issue and imposed restrictions on Tibetans gaining Bhutanese citizenship, despite sharing close socio-religious ties with Tibet.[66]

Bhutan’s self-interest also extends to economic self-sufficiency and self-reliance.[k] While its first phase of diplomatic expansion was largely shaped by its need to survive, the second was mostly determined by its economic needs. Two factors shape Bhutan’s economic foreign policy: a) its political and security calculations, as seen in its rejection of Chinese grants and incentives, as well as the BRI proposals;[67] and b) preservation of its unique identity derived from its concept of ‘Gross National Happiness (GNH)’ that focuses on sustainable development and environmental protection.[l] Bhutan’s economic foreign policy has thus largely focused on limited economic growth based on domestic needs rather than massive expansion. Though it is part of the Bhutan-Bangladesh-India-Nepal (BBIN) initiative which has entered into various infrastructure-related agreements, it opted out of the BBIN Motor Vehicles Agreement (MVA) by which vehicles from any one of these countries could travel in the others with less restrictions.[68]

Bhutan’s Current Challenges

Bhutan’s foreign policy determinants are facing a strong challenge from certain internal and external changes. Over the past two decades, Bhutan has witnessed a changing economy, a generational shift in aspirations as young people access the internet in large numbers, a democratic transition with the king relinquishing most of his powers to an elected government, the rise of China, and a changing geopolitical structure. All this is pressuring the country to settle its long pending territorial disputes with China, diversify its foreign relations further, and accelerate economic growth.

Economic Changes

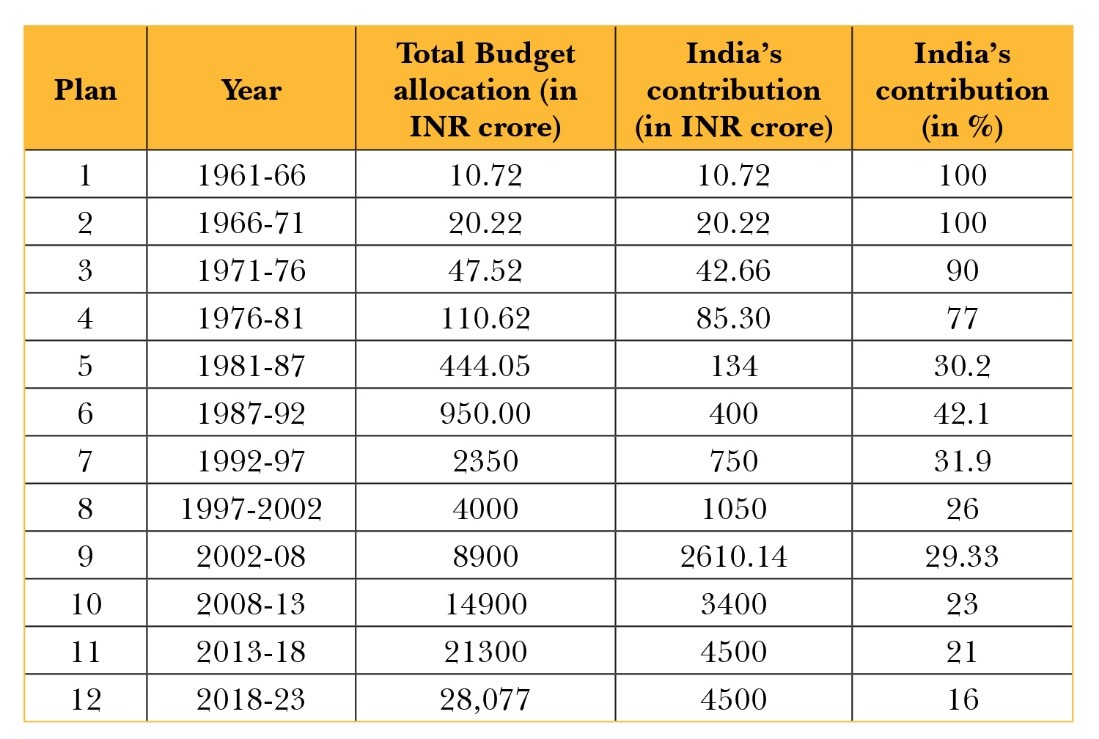

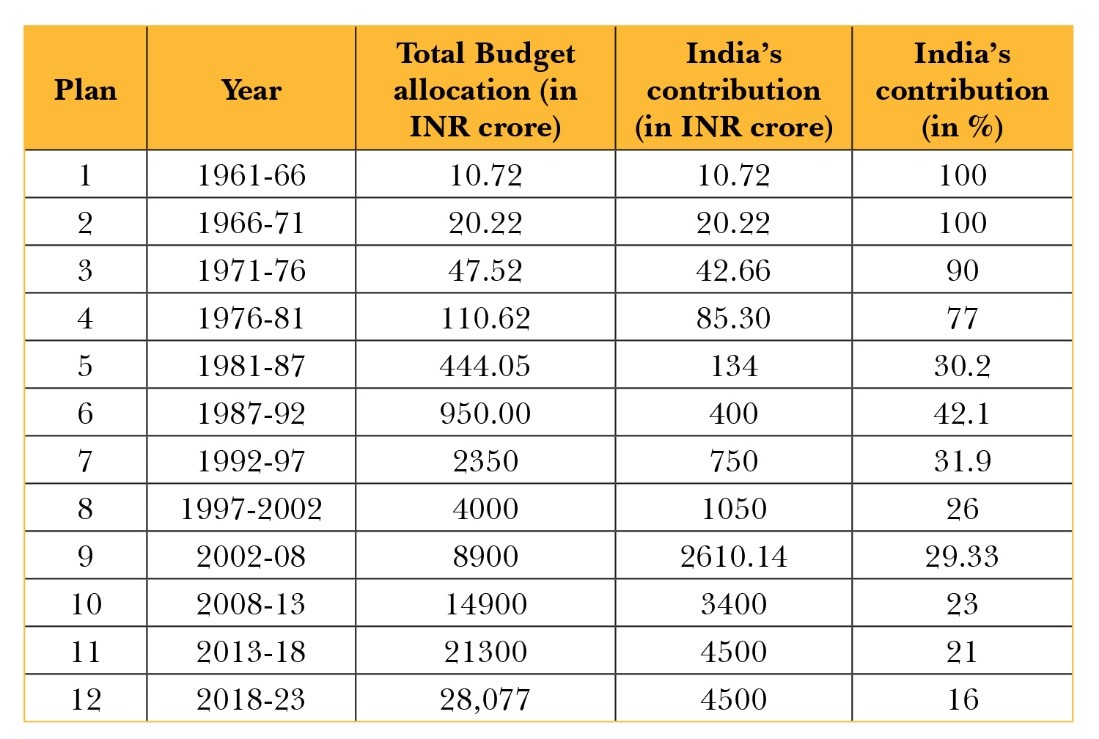

India has consistently assisted Bhutan by funding its Five-Year Plans (see Table 2), its hydroelectric power and major infrastructure projects, and providing it with subsidies, grants and currency swaps.[69] India also accounts for 90 percent of Bhutan’s imports and 77 percent of its exports, following the Free Trade Agreement between the two countries.[70] This assistance has helped Bhutan’s economy grow rapidly. Its gross domestic product rose from USD 128 million in 1980 to USD 400 million in 2000. By 2020, this had grown further to USD 2.3 billion, or nearly six times in two decades.[71]

Table 2: India’s Contributions to Bhutan’s Five-Year Plans

Sources: Embassy of India, Bhutan; Bhutan’s 12th Five Year Plan [72]

To be sure, growth has also increased Bhutan’s expectations, improved its socio-economic indicators, and raised employment demand. In 1960, Bhutan had only 11 educational institutions with 400 students. Today, literacy among its youth (15-25 years) is 92 percent with 1,132 educational institutions in the country and 191,553 students, i.e., around 25 percent of the total population consists of students.[73] Its poverty level reduced from 23 percent in 2007 to 8 percent in 2017; its per capita income has increased by 450 percent in the past 20 years.[74], [75]

However, Bhutan’s economic growth model has not been able to generate enough jobs. Around 70 percent of its unemployed are young people.[76] The loans, grants, lines of credit, and hydropower projects are making Bhutan more dependent on India rather than promoting a self-sustaining economy.[77] India’s use of Indian labour, capital, technology and goods for these projects—rather than local—has invited criticism from several sections in Bhutan. India’s imports of hydropower electricity that are cheaper than market prices has only heightened these criticisms.[78]

Further, India has failed to deliver some projects on time and in the volumes expected, and this has contributed to Bhutan’s rupee debt. Currently, India has only been able to generate 1,416 MW of the promised 10,000 MW of hydropower.[79] The delay in completing these projects has increased Bhutan’s costs and the size of its debts to India. Of Bhutan’s current debts, 94 percent are related to its hydropower projects alone.[80] This is in addition to Bhutan’s continuing trade deficit with India.[81] This debt and deficit have created a perception among Bhutanese that India is exploiting Bhutan and taking back whatever it is investing in the country.

Continuing with this model will perpetuate dependence on India and increase unemployment and debt for Bhutan’s future generations. Bhutan is in desperate need of foreign investments and more jobs for its youth, who comprise 60 percent of its population.[82] It has been focusing on foreign direct investment (FDI) since the early 2000s; its first democratic Prime Minister, Jigmi Thinley, established diplomatic relations with 31 countries in his short five-year tenure. He even tried to establish ties with China.[83]

Bhutan’s needs—economic, scientific, and technological—were reiterated by the King on the country’s 112th National Day on 17 December 2020.[84] Although India has shown interest in collaborating with Bhutan in these sectors,[85] a lot remains to be done.

The Internet and Generational Shift

Economic growth has coincided with a generational shift. Bhutan opened up to television and the internet in 1999.[86] Economic progress and gradual liberalisation has increased the number of newspapers, radio channels, and cable TV operators in the country.[87],[88] It has also enabled progress in Information Communication Technology (ICT) and digitalisation. Today, Bhutan has over 762,975 mobile and 729,733 internet subscribers which amounts to nearly 97.4 percent of the population.[89]

Indeed, ICT has taken Bhutan by storm. It has exposed the youth to the world outside more than any previous generation. Globalisation, exposure to social media, and education have triggered a shift in their thinking, aspirations, values, and priorities.[90] Young people’s political and economic views and ambitions are more global now than regional.[91] They are active participants in key debates about the country’s present and future. Social media is even overshadowing traditional media in various ways.[92] Historian Karma Phuntsho notes: “Bhutan has changed much more in the past 50 years than in the 500 years before that.”[93]

Digitalisation has also been influencing the country’s foreign policy. Unlike in earlier times, digitalisation has enabled people to challenge both the government’s and traditional media’s narratives on foreign policy.[94] While the older generation was keen on staying loyal to India, the young are eager to see Bhutan play a global role.[95] This generation has not faced the economic and political turmoil of its predecessors, and is thus not particularly grateful for India’s assistance. Nor are they necessarily hostile to India. Lack of people-to-people contact with Tibet has also distanced this generation from sympathising with the Tibetan cause. They are less apprehensive of China compared to their predecessors.[96] Indeed, they see China’s economic might and growth as potentially helpful in improving Bhutan’s economy.

This generation’s sense of identity, and indeed its ideology, are yet to be structured,[97] and this makes it vulnerable to different perceptions of the country’s foreign policy. Chinese apps, such as WeChat and TikTok, have become popular despite their security loopholes. This has the potential to expose young people even more to anti-Indian sentiments.

Some sections even perceive India as a hurdle in Bhutan’s border negotiations with China. Bhutan’s refusal of China’s ‘package deal’, and India’s alleged involvement in the 2013 elections, have often been cited to substantiate this view. The Doklam issue is a case in point. As tensions increased, some Bhutanese criticised both India and China on social media and called out the Bhutanese government for its overreliance on India.[98] There are those who see India’s economic embrace as “suffocating”.[99] With increasing reliance on social media, young people are becoming more vocal and critical of Bhutan’s foreign policy and India’s role.

Democratic Transition

Before its democratic transition in 2008, Bhutan’s foreign and security policy was set solely by the King. Today, though the King still has a pivotal role, there are multiple actors shaping foreign policy.[100], [101] The prime minister and his Cabinet have the power to formulate foreign policy based on ideology and governance needs. Bhutan’s Parliament can debate any issue and influence the government’s decisions. Even so, the King still has the power to morally guide the country’s foreign policy and is also Supreme Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces. Since there is no defence minister, as Supreme Commander, the King remains de-facto decision-maker.[102]

Nevertheless, the influence of democracy on Bhutan’s foreign policy is already visible.[103] Bhutan has witnessed three elections in all, and each one has brought a new ruling party and a new prime minister to power. Although all of their foreign policies have prioritised self-interest—i.e., economic growth and boundary negotiations with China—their perception and foreign policies have differed from one another.

For instance, the first PM, Jigmi Thinley, drastically expanded diplomatic relations, adding another 31 countries to those Bhutan already had ties with, seeking to increase the inflow of FDI. He also tried to establish diplomatic relations with China. This was perhaps a product of his perception of India’s growing limitations in meeting Bhutan’s economic needs.[104] The second PM Tshering Tobgay’s foreign policy was a product of Bhutan’s pragmatic constraints. He dismissed the idea of establishing diplomatic ties with China and instead focused on economic benefits through sub-regional connectivity with India, the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) countries, and the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC) members. The current PM, Lotay Tshering, has also been more pragmatic and is focusing on investments and connectivity. So far, there are no signs of establishing diplomatic relations with China, and relations with India remain as usual.[105]

To be sure, being a landlocked country closely aligned with India, Bhutan has limited space for diplomatic manoeuvres. But given its changes in government and each government’s perception of the world, its foreign policy has become more vulnerable to shifts and criticisms than in the past. With democracy and social media flourishing, the number of stakeholders is increasing, and so are the debates on India’s projects and assistance.[106] The private sector, lobby groups, and nationalist electoral rhetoric will likely play an increasing role in the country in the coming years. Elected governments will be more vulnerable to scrutiny on the country’s territorial losses to China, and its economic policies vis-à-vis foreign investments and projects.

Rise of China

The rise of China has also been impacting Bhutan, in both negative and positive ways. Starting from the 1950s, China adopted a carrot-and-stick approach to Bhutan. These economic incentives, however, were rejected by the Bhutanese on several occasions.[107],[108]

However, China’s economic growth is feeding the need for deeper economic ties with it, amongst Bhutanese citizens and especially its private sector. The business sector complains of the additional cost incurred and other issues while importing Chinese goods through India. Small Bhutanese merchants also continue to smuggle cheap Chinese goods and artefacts into the country.[109],[110] Chinese tourists in Bhutan have vastly increased since 2008 – till 2015, there have been 10,000. These tourists generate revenue by spending lavishly, around USD 250 on their visas alone,[111],[112] while their counterparts from India barely spend USD 15 per day. This has made Bhutan’s need to have economic and diplomatic relations with China more urgent.

By 2010, China had begun exporting farming and telecommunications equipment to Bhutan.[113] In 2012, a company owned by the Bhutanese PM’s son-in-law won a tender to buy Chinese-made buses to sell in Bhutan.[114] This indicates a growing relationship between lobby groups, political parties, and business elites in Bhutan with China.

China has also increased pressure on Bhutan over the boundary issue. It began by releasing maps showing disputed territory as Chinese, conducting border intrusions, and encouraging Tibetan herders to move along the border. In the 2000s, it increased its patrols along the border, and built roads in the region, some of which intruded into disputed territory, more so after Bhutan rejected China’s package deal and extended its claims. In 2010, Medha Bisht, an expert on India-Bhutan relations, had categorised China’s negotiation strategy into the engagement, redistribution, and normalisation phases.[115] A lot has changed since then.

Post-2010, a new and fourth phase of negotiation has—what this paper calls the ‘enforcement phase’. China is building permanent settlements on Bhutanese territory. The aim is to use its material might to compel Bhutan to negotiate and end the border dispute as early as possible.

China began building its first village ‘Gyalaphug’ within Bhutan in 2015. Chinese herders who would earlier intimidate Bhutanese grazers have been settled to the North of the Beyul and Menchuma regions. More such villages have been built since. In 2017, China tried to build a road in Doklam that would lead to a Bhutanese military post, which would also run close to India’s Jampheri ridge. This led to the subsequent military standoff between India and China. After that ended, China has continued improving military infrastructure in the region. [116]

China also laid claim to the Eastern region of Sakteng in Bhutan for the first time in 2020. The same year, it also finished constructing Pangda village in the Western region. In 2020 and 2021, satellite images showed China building another four villages in the Western region.[117],[118] In 2021, China passed a new “Land Borders Law”, which seeks to increase the number of border town constructions and settlements, and strengthen borderland defence.[119]

In Bhutan too, there is growing demand to end the border dispute. This has been reinforced with the emergence of democracy and rise of social media. Debates in the National Assembly often discuss Bhutan’s inability to cope with Chinese intrusions.[120] Given India’s interests in the strategic regions of Western Bhutan, Bhutan has also grown more cautious as India-China hostility intensifies. It is increasing the restrictions on deployment of non-IMTRAT Indian Army units in the country, and keeps its own army’s operational training by India below the radar.[121]

Bhutan has also continued its old tactic of strategic silence.[122] It has even rejected the evidence of the satellite images showing construction of new villages by China on Bhutanese land. It does not want to offend either India or China, and also seeks to limit domestic anti-Chinese sentiment that could further complicate border negotiations. Talks with China were continuing till the Doklam standoff but have stalled since then. The countries are yet to organise their 25th round of negotiations, which will also include discussions on the new claims on Sakteng.[123] However, the 10th ‘Expert Group Meeting’ was held in 2020 and an MoU agreeing to a three-step roadmap towards solving the border dispute was signed in 2021.

Impact of Global Transformation

Finally, as the world goes through structural transformation, Bhutan finds itself caught between two growing rivalries – India-China and the West-China. If it is seen as excessively pro-India and uninterested in resolving the border dispute, Bhutan will be looked at askance by China and will only invite more pressure from it. There is also Chinese apprehension that Bhutan could be used to monitor and exploit the situation in Tibet.[124] Bhutan also needs to solve this dispute before the relations between China and the West worsens, and the landlocked state is dragged into big-power politics. Its stance in the UN general assembly following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine revealed these fears of being a small landlocked state that is straddling big powers. Its stress on maintaining a rule-based order, good neighbourly relations, peaceful co-existence, and the importance of defending the UN Charter that guarantees the existence of small states underline its broader concerns. [125]

Implications

Relations with China

The global changes mentioned in this paper carry vital implications for Bhutan’s foreign policy vis-à-vis China. Bhutan’s foreign policy has always prioritised its territorial integrity and sovereignty. It has been defensive of its territories through its 24 rounds of negotiations with China. But, with China in its enforcement phase and the evolving geopolitical structure, this defensive posture has had its repercussions. Chinese assertiveness has also increased.

Other factors such as the transition to democracy, the growth of social media, and the economic needs of Bhutanese business and its youth—who are looking at China for economic opportunities—also challenge the state’s traditional narratives and policies.

As noted earlier, Bhutan’s foreign policy is focused on the Balance of Threat. China’s pressure has no doubt pushed Bhutan to the negotiating table but its threat perception remains. China’s continued violation of the 1998 agreement, its building of permanent settlements on Bhutanese territory, and its raising of new claims—after offering a package deal and 24 rounds of negotiations—is causing concerns about China’s real intentions. The economic incentives dangled by China are also seen as a threat. There is fear that Chinese investments and projects could swallow up Bhutan’s economy and ruin its environment.

Both progress in diplomatic ties and economic engagement are unlikely, unless China counters these perceptions. At present, Bhutan’s only priority is to end the territorial dispute. It has two options: it can proceed with the package deal, though that is unlikely given Bhutan’s lack of trust in China and its common security concerns and economic interdependence with India; or it can make concessions within the sector-wise negotiations of the disputed borders. The outcome of the border talks will likely not be publicised for domestic reasons, and will happen only after consulting with India.

The extent to which China counters Bhutan’s perception of threat will dictate the trajectory of Bhutan’s policy towards it.

Relations with India

As long as China is unable to counter Bhutan’s threat perception, Bhutan is compelled to cooperate with India. Bhutan will thus likely continue its close military and strategic relationship with India, abiding by the concept of common security. However, its self-interest will also ensure it maintains its strategic silence on India-China matters and avoids an explicit alignment with India. This will continue as the rivalries of the new geopolitical structure intensify.

On the other hand, since the democratic government is responsible for Bhutan’s foreign policy—internal politics, economy, social media and the generational shift will all play an influential role. Primarily, there is increasing pressure on the government to promote economic growth and reduce the country’s unemployment. This will influence the country’s economic foreign policy and will exert pressure to attract FDI from countries beyond India, including China—which will be looked upon with suspicion by New Delhi.

Nonetheless, since Bhutan continues to be integrated with South Asian economies such as India, Bangladesh, and Nepal, it expects greater sustainable regional connectivity and trade to increase its economic growth. India’s economic and connectivity policies will be observed and debated closely by political elites and the younger generation. Indeed, Bhutan’s economic growth model and the nature of India’s economic assistance may need a drastic change. India will need to sustainably invest in Bhutan’s services sector, keeping in mind its GNH and domestic employment demands. For now, however, India’s economic relations with Bhutan continue to be dominated by hydropower projects.

India should thus be wary of negative perceptions about itself in Bhutan, especially those emanating from its political, economic and foreign policies. These have the potential to open a Pandora’s Box that can complicate the India-Bhutan bilateral security mechanism, and diplomatic and economic relations. India should continue being more sensitive to Bhutan’s strategic silence, diversifying its economic engagements, and seeking boundary negotiations with China.

Conclusion

Bhutan’s bilateral relations with India and China can hardly be independent of broader Sino-India relations. Bhutan has thus maintained a special relationship with India and a largely neutral relationship with China, albeit without any diplomatic ties. Its foreign policy is determined by three factors: assuring territorial integrity and sovereignty; maintaining a balance of threat; and abiding by its self-interest. However, over the past two decades, Bhutan has been witnessing internal and external changes that are forcing it to settle its longstanding territorial disputes with China, diversify its foreign relations, and accelerate economic growth.

Nonetheless, Bhutan continues to face various constraints because of its geopolitical positioning. It will keep trying to solve its territorial disputes with China while avoiding any in-depth engagement. It will continue being closely aligned with India for its economic growth and political survival. However, it is India’s sensitivity to Bhutan’s strategic silence, their diverse economic engagement, the boundary negotiations, and China’s ability to counter Bhutan’s perceptions that will dictate the future trajectory of Bhutan’s foreign policy.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PDF Download

PDF Download

PREV

PREV