-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

PDF Download

PDF Download

Ankush Banerjee, “The Case for Civil-Military Fusion to Enhance India’s Military Training Ecosystem,” ORF Occasional Paper No. 503, Observer Research Foundation, October 2025.

Much has been written about how the advent of disruptive technologies, such as Artificial Intelligence (AI), drones, and quantum communications, is transforming battlefields and causing the next wave of Revolution in Military Affairs (RMA).[a] Weapons systems designed from such technologies have been characterised by autonomy, increased lethality, accuracy, and connectivity.[1] Theorised under the umbrella term of ‘RMA’, such technologies have exhibited massive potential to influence the conduct and outcome of modern conflicts, witnessed most notably with the use of AI-based imaging and facial recognition, and unmanned aerial vehicles in the Ukraine-Russia, and the Israel-Hamas theatres of conflict.[2]

This paper will start by briefly delving into the contours of this new kind of RMA. While it is beyond the scope of the paper to sketch the evolutionary history of the concept, a comparison of two foundational definitions will serve as a useful starting point. Hundley (1999) describes RMA as “a paradigm shift in the nature and conduct of military operations which either renders obsolete or irrelevant one or more core competencies of a dominant player, and/or creates one or more new core competencies, in some new dimension of warfare.”[3] Germany’s concerted use of Luftwaffe, Panzer and Armoured Divisions under its Blitzkrieg doctrine, overwhelming the French Maginot Line in 1939,[4] is an apt illustration of Hundley’s definition. However, the definition is limited by its focus on the competencies of stakeholders, and says nothing of what goes into the making of those competencies.

Conversely, Krepinevich (1994) provides a more holistic account of RMA, as “the application of new technologies into a significant number of systems combined with innovative operational concepts and organisational adaptation in a way that fundamentally alters the character and conduct of conflict.”[5] This definition amalgamates three important facets of warfare—i.e., new technologies, innovative operational concepts (tactics, doctrines and strategies), and organisational adaptation via learning or training.

Scholarship about disruptive, military technologies has broadly focused on the first two facets: new technologies (their development and weaponisation), and the way their proliferation and use stand to alter existing war-fighting frameworks (accompanying changes in tactics, doctrines, and strategies). For instance, numerous scholars have alluded to “informatisation and intelligentisation” as two key drivers of this new wave of RMA.[6] The question of how to prepare the human element for the next-generation battlefield, i.e., enhancing training paradigms, has remained largely underexplored. Taking this as a starting point, this paper argues that the ongoing wave of RMA necessitates an evolution in the military training paradigm.[b] It explores how leveraging existing civil talent and expertise in hitherto underexplored ways carries immense potential for enhancing the military training ecosystem in India.

Around the world, including in India, the democratic framework brings with it structural, epistemic, and existential separation between the military and civil society.[7] Such a separation manifests in both ideological and material terms. Ideologically speaking, discipline, hierarchy, and duty become some of the salient values that distinguish the military from the larger civil society, whereas materiality manifests as geographic separation between military cantonments and civilian enclaves, as well as differences in Human Resource functions, such as transfers, structured routines, and prolonged separation from families.[8]

One domain where such a gap reflects most acutely is training. The three Services of the Indian Armed Forces have an elaborate, widespread network of training schools and establishments. Most of these institutions have faculty comprising service officers and senior ratings, reasonably robust internal audit mechanisms to ensure updated curricula, and state-of-the-art infrastructure for maximum training efficacy. Some amount of civil-military collaboration already exists, particularly in the form of Memoranda of Understanding (MoUs) between military-training establishments/schools and civil-academic institutions. Civil-military collaboration also manifests in officers taking up different courses at civil academic institutions, and later being posted to military training schools in instructional roles. In addition, cross-institutional interactions through visits, guest lectures, and faculty exchange programmes also take place between civil-academic and military-training institutions. Nonetheless, most of these military-training institutions function as self-sufficient, academic enclaves, and deeper interactions with non-military individuals or entities are not institutionalised.

Further, the military training ecosystem has been largely characterised by certain insularity, given that the roles and processes for which military personnel are trained seldom find overlaps in the civil domain. However, the proliferation of disruptive technologies in warfare and equally game-changing technologies in the field of education, and their accompanying implications on the civil domain call for a reconsideration of the insularity of the military training paradigm. Analysts have highlighted how limited civilian participation in Professional Military Education (PME) has been a long-standing lacuna that precludes possibilities of more holistic, well-rounded PME.[9]

It also merits attention that many of the emerging technologies which will, or are playing a disruptive role in military operations, are already in advanced stages of maturation in the civil domain, either in academic institutions or private sector firms. Given the expertise of the civilian domain in technologies such as AI, Robotics, and Big Data analytics, there is a need to explore how different degrees of Civil-Military Fusion (CMF) can improve training and prepare armed forces personnel for next-generation warfare. This in no way casts doubt on current training practices, i.e., the efficacy of military trainers and the self-sufficiency of training schools in deciding and auditing curricula. Through a strategic revamp, civil expertise and resources can be optimally leveraged to enhance training processes.

CMF has already proven to be a crucial factor in other sectors, such as research, development, and adoption of various technologies, particularly through initiatives such as Innovations for Defence Excellence (iDEX) and ‘Make in India’.[10] There is ample scope to holistically explore how different degrees of CMF at broader institutional levels can enhance training processes, by making civil expertise and resources more accessible to military personnel, given the following considerations:-

Building upon the above, this paper aims to articulate lines of effort for the infusion of CMF in the Indian Armed Forces training ecosystem; identify areas of training where civil-military elements can be amalgamated to enhance military training effectiveness; and, based on these considerations, make recommendations to infuse CMF in the military-training ecosystem.

Civil-Military Fusion (CMF) refers to the “convergence of military and civilian resources and systems for maximising a nation’s ability to express its comprehensive national power during war and peacetime.”[11] This concept first found salience during the 1980s when China began using its civil and military enterprises to resuscitate these domains from prevailing economic crises. Chinese Premier Deng Xiaoping’s “Sixteen Charter” slogan from that time called for “combining military and civil, combining peace and war, giving priority to military products, and making civil support the military.”[12] Over the ensuing 40 years, the success of China’s endeavours in integrating/fusing strands of their Civil-Military Industrial complexes has compelled other countries, most notably the United States (US), to incorporate new paradigms of CMF in their security structures. The United States Army Futures Command (USAFC), established in 2018 “to ensure the Army and its Soldiers remain at the forefront of technological innovation and war-fighting ability,”[13] stands as a testament to this. It focuses on amalgamating both public and private sectors to create a culture of innovation and technological leapfrogging to counter Chinese ascendancy. The infusion of CMF has provided manifold technological breakthroughs in Israeli and Turkish contexts as well.[14]

CMF, in the aforementioned countries, has primarily focused on expediting technology development towards weaponisation. Such processes entail very different institutional strategies compared to those required to infuse CMF in training.[15] For example, the evolution of the deadly Turkish Bayraktar TB2 drones—one of the startling examples of CMF in recent times—has a number of factors behind its successful development: individual initiative and brilliance (that of Selcuk Bayraktar, its developer); the Turkish government’s open and unconditional support to private enterprise (Bayraktar’s family company, Baykar Technologies); and geopolitical compulsions (Türkiye borders Iran, Iraq, Syria, Georgia, the EU, and it faces Russia across the Black Sea).[16]

The lines of institutional efforts required to infuse CMF for training can be very different from those needed to attain technology maturation. Further, India’s political structure and civil-political-military complex are different from either the US, China, Israel, or Türkiye. Thus, a more nuanced approach may be in order.[17]

Preparing the ‘human element’ refers specifically to institutional training processes. Conceptually, training is a ‘performance improvement tool’[18] administered when there is a gap between existing and desired competencies of personnel. This gap is called a ‘training need’. A training need could arise because of several factors, such as a change in organisational processes and characteristics of personnel (such as motivation and entry qualifications), the induction of new technologies, emergence of new training methodologies, or larger industrial/environmental processes.[19]

Given the complexity of contemporary warfare, there is a need to make training more practical and realistic, preparing personnel to function in complex operational environments. In this regard, scholars such as BS Dhanoa have drawn attention to the potential of training aids such as simulators and gamification in transforming the military training paradigm,[20] albeit in the context of COVID-19-induced social distancing. In light of these considerations, CMF will entail efforts along the following three different, but interlinked lines:

The Indian academic landscape is thriving with both legacy and new institutions, such as IITs, IISc, IIMs, NITs, and JNU (Jawaharlal Nehru University), that have been at the cutting-edge of their respective fields. These institutions cover a range of domains such as technology, international relations, medicine, and logistics. Further, in the contemporary milieu, measures such as MoUs and seats in specific institutions for officers to undergo postgraduate courses already exist as means to leverage the expertise of many of these institutions.

There are other avenues through which India’s academic expertise can be utilised. These will be conceptualised bearing in mind the one crucial gap that has existed between academia and armed forces, i.e., the ‘knowledge gap’ between theoretical/academic insights held by academicians, and how armed forces personnel can be trained to apply the same to find practical solutions to real-time military problems. The infusion of CMF, when implemented appropriately, will help bridge this gap. Second, institutional mechanisms need to be conceptualised such that the armed forces can attract the best teaching/research talent from academia for short durations in their own training environments. This will infuse fresh ideas and training methodologies into the training ecosystem.

Ever since India witnessed the startup boom in 2016, the country’s private sector landscape has been overwhelmed by ‘unicorns’.[21] Many of these have been Educational Technology (edtech) startups, which have revolutionised the conduct of education. The COVID-19 pandemic further accelerated the growth and proliferation of these startups.[22] According to estimates, India has become the second-largest market for e-learning after the US.[23] There is a need to explore the expertise of Indian edtech startups in adopting new educational and training methodologies.

Flowing from the above, most new-age training methodologies conceptualised and used by edtech startups—such as simulators, gamification, e-classrooms, and e-libraries—require internet connectivity. However, the internet has, from the beginning, been anathema to the armed forces. This is understandable because of the requirements of the highest levels of information security.

However, the armed forces will have to devise hardened, networked systems that can be used on the internet for non-combat and training purposes in the near future. There is a need to articulate these technical infrastructural or architectural requirements and work in tandem with civilian stakeholders towards infusing existing training processes with more engaging training methodologies.

India’s Ministry of Defence (MoD) employs the largest workforce among all central government ministries. There are some 400,000 defence civilians under the MoD, employed in various agencies such as the Defence Research and Development Organisation, Director General Quality Assurance, and Canteen Stores Department.[24] There is a need to explore how the ambit of ‘defence civilians’ can be expanded and infused with institutional training avenues focused on directly enhancing war-fighting efficacy. This will take the pressure off uniformed personnel for time-intensive responsibilities such as working on technology maturation and the development of training aids.

CMF does not only involve civil academia and private sector engagement, but also fostering more synergy among civil and military institutions and personnel by leveraging joint and inter-service training avenues. Currently, few military officers undergo any training exposure across the institutions where civil services officers train. Examples of these, occurring few and far apart, include training in niche verticals at institutes such as the Arun Jaitley National Institute of Financial Management in Faridabad, and the Nainital Academy of Audit and Accounts in Shimla. However, these endeavours are mostly removed from the mainstream training paradigm. A small number of civil service officers attend the Staff Course at Defence Services Staff College (DSSC), Wellington, Tamil Nadu.

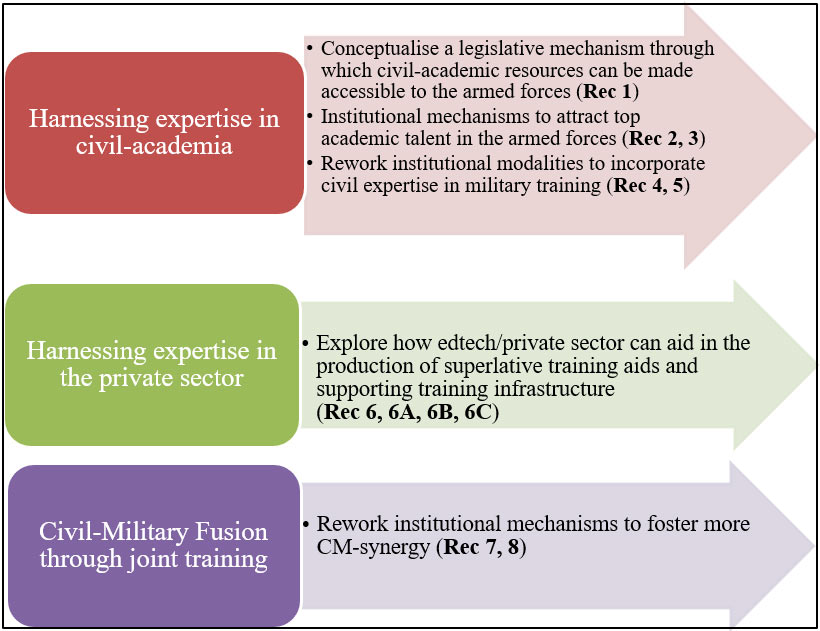

The first time that large numbers of civil and military officers train together is at the National Defence College (NDC). While the NDC provides much-needed inter-services exposure, it comes late in an officer’s career, i.e., at more than 25 years of service. Given that next-generation warfare will require a whole-of-government approach, as highlighted in 2022 by Prime Minister Narendra Modi,[25] there is a need to identify avenues in the training ecosystem where such an approach can be implemented through joint training initiatives entailing civil services (including DRDO scientists) and military officers. There is also a need for shorter orientation courses for military and civil service officers to train alongside each other at junior, i.e., Under-Secretary/Lieutenant Commander-equivalent, and mid-level leadership, i.e., Deputy Secretary/Commander-equivalent levels. To summarise, there are three broad paradigms of CMF infusion, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Overheads for Infusing CMF in Training

Source: Author’s own

Recommendation 1: The Indian Armed Forces, through the Department of Military Affairs (DMA), should take up a case for legislation wherein all government and government-aided educational institutions are mandated to provide training to a certain number of armed forces personnel each year.

The armed forces, through the DMA, should draft and forward a ‘Defence Empowerment Bill’ via the MoD. As mentioned earlier, numerous MoUs exist among civil-academic and military-training establishments. These cover a wide range of academic/training and research facets, such as the award of degrees (e.g., undergraduate degrees by JNU to NDA cadets; postgraduate degrees by University of Madras to DSSC-qualified officers; and PhD degrees by Mumbai University to officers at the Naval War College, and by Osmania University to officers at College of Defence Management); undertaking joint research (such as the ‘DRDO Industry Academia-Ramanujan Centre of Excellence’ established at IIT-Madras to conduct research in advanced defence technologies);[26] and the conduct of faculty improvement programmes by civil-academic experts at defence-training establishments. This DEB should aim to formalise civil-military collaborations and open up existing civil capacity for military training. It is proposed to mandate all government and government-aided educational/academic institutions towards the following:

Set a quota of seats for armed forces personnel in all long-term (one+ year), mid-term (of one-three months’ duration), and short-term (one- to three-week duration) programmes.

Currently, India’s top academic institutions conduct many long-term, mid-term, and short-term courses focusing on specific domains. While seats are reserved in the IITs for postgraduate courses, there is a need to make various mid-term and short-term Management and Faculty Development Programmes (MDPs and FDPs) accessible to the armed forces personnel. This is akin to the practice wherein various courses run by the Department of Personnel and Training, such as Direct Trainer Skills’ Course, and Design of Training Course, are made available to armed forces personnel. Setting a quota of seats in relevant courses will pave the way for having a long-term, sustainable model to train personnel in niche verticals.

Conceptualise training modules to address specific training objectives aligned to the needs of the armed forces and emerging challenges in the field.

The ‘knowledge gap’ referred to previously, also manifests as an ‘application gap’, i.e., a gap between what is being taught to defence officers during niche postgraduate courses at civil institutions, and how to convert this knowledge into practical, applicable acumen, which can help address institutional needs. The DEB should mandate civil-academic institutions with vertical expertise in specific domains to conceptualise short-term training modules in those domains for a select set of personnel, that will empower them to address real-time institutional challenges. Two indicative examples are outlined in Table 1.

Table 1: Indicative Training Modules to Address Specific Training Objectives

| Name of Capsule | Training Objective | Indicative Syllabus and Duration | Target Group and Institution |

| Blockchain (BC) Technology and Supply Chain Management | The trainee will be able to apply principles of BC technology towards effective supply chain management of critical military stores | · Basics of BC and Military Supply Chain - Overview, types, vulnerabilities. · BC architecture and integrating it within the military supply chain. · Two use cases: (aa) Critical Weapon Store, (ab) Personnel Demand Items. · Duration: 4 weeks. | (aa) Supply officers from three services (Major/ Lt Col equivalent ranks). (ab) Abridged version of IIM-Calcutta’s 1-year Advanced Programme in Supply Chain Management[27] |

| Capsule on Nanotechnology in Medicine | The trainee will be able to apply principles of nanobiotechnology towards the management of chronic and infectious diseases. | · Biology of Cell-Cell Interactions · Nanomedicine and nanosurgery · Nanodevices (smart sensors, smart delivery systems, magnetic nanodevices, nano biosensors) · Nanobiotechnology in chronic and infectious diseases. · Duration:12 weeks. | (aa) Medical and Technical Officers from three services (Major/ Lt Col equivalent ranks). (ab) Abridged version of Centre of Pharmaceutical Science and Research’s 12-month PG Diploma in Nanotechnology[28] |

Sources: As cited; Author’s own

Set up ‘university-affiliated research centres’ in select universities/higher educational institutions.[29]

Research on defence technologies is still closely guarded. As a measure of using CMF to enhance the military’s intellectual discourse and expediting technology maturation, ‘University Affiliated Research Centres’ (UARCs) at relevant academic institutions should be set up, focusing on specific defence technologies. These could be staffed by technically-qualified officers, university professors, and contractual subject matter experts and civilian researchers. Further, the issue of security ought to be covered via Non-Disclosure Agreements and the Official Secrets Act to protect civilians, as is the practice for civilian researchers at BARC (Bhabha Atomic Research Centre), ISRO (Indian Space Research Organisation), and other institutions of national importance. UARCs will de-clutch the overt dependence on DRDO Labs, and provide the armed services access to human capital, technical infrastructure, and the freedom to experiment and explore. To illustrate from another context, the United States’ Department of Defense has 14 such Defense Labs at select universities. At times, private sector enterprises also use these labs for technology testing and maturation. Examples include the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Lab, MIT’s Institute for Soldier Nanotechnology, and Georgia Tech Research Institute Applied Systems Laboratory.

Formulate regulations and concessions for armed forces personnel undergoing training at civil institutions.

Some 220-240 officers (of Major/Lt Col equivalent ranks) attend postgraduate-level courses in various civil-academic institutions. One of the features of the DEB should be to formalise the structure of these courses in a way that while the first year is spent on campus, at least one semester of the second year, i.e., typically six months, is dedicated to project work, and the internship, i.e., eight to ten weeks, must be spent at the concerned nodal directorates/training schools. These will help such officers detach from routine professional activities. Further, during these periods, the officers should be given tangible institutional challenges which they should endeavour to address with the help of their academic supervisors. Seen this way, these officers will serve as a live knowledge link between academia and the field.

Recommendation 2: Create avenues that attract top academicians and professionals from national institutions to serve as Faculty at defence training academies/institutions for specific time periods (two-three years).

Currently, a majority of instructors at defence training establishments are service personnel, while a minority are from the civilian domain. However, the latter serve for long durations, thereby getting assimilated into the defence ecosystem. There is a need to have flexible avenues that introduce new ideas into the system. This can happen by attracting top academics and professionals in specific fields for short (two-three years) durations under the ‘Chair of Excellence’/’Distinguished Chair’ framework with attractive emoluments and reward mechanisms. Some defence institutions have such positions, but those are occupied mostly by retired officers. The scope of such measures needs to be expanded, i.e., consider having more than one ‘Chair of Excellence’. The envisaged charter of duties of such faculty members and proposed reward mechanisms are summarised in Table 2.

Table 2: Responsibilities and Incentives to Attract Top Teaching and Research Talent

| Responsibilities |

| Conduct training sessions for faculty and trainee officers. |

| Guide meritorious officers in vertically-specialised research projects related to their field. |

| Incentives to Attract Talent |

| Financial assistance in the form of monthly emoluments/grants in suitable pay bands (13-14), in addition to research grants for purchasing books, travel, journal subscriptions, and other academic resources. |

| Research assistance in the form of access to unclassified defence equipment, files, and academic resources. |

| Felicitation for outstanding contributions in the form of awards commensurate with their achievements/stature. For instance, senior professors and experts making significant contributions can be awarded VSMs, NMs, SMs (equivalent), while other meritorious contributors can be awarded CDS, CAS/COAS/CNS commendations. |

Source: Author’s own

This measure will accrue benefits in the following ways:

Recommendation 3: The MoD/armed forces should identify specific undergraduate/postgraduate courses at institutions of national eminence and give scholarships to meritorious, underprivileged candidates, with a caveat of serving in vertically specialised billets of the Armed Forces for a stipulated time period of 10 (+four) years. Sponsored candidates should be inducted as Group A/B ‘defence civilians’, thus insulating them from mandatory rotations/posting requirements, and allowing them to build vertical expertise in technology development through long-term engagement in the UARCs discussed previously.

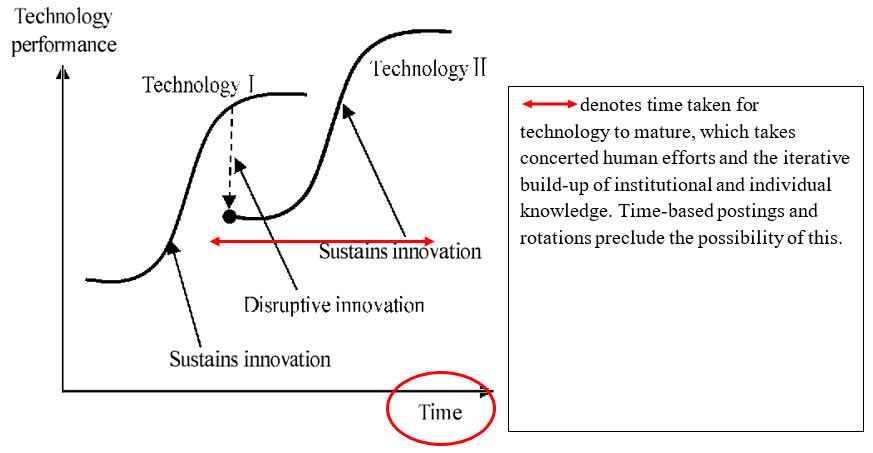

In 2021, a serving Indian Army officer and scholar, Vivek Gopal asserted in a paper that, “There is an urgent need to change the mindset that services exist only to fight.”[30] Most entry schemes in the armed forces are to fulfil primary, secondary, or ancillary combat roles. This recommendation stems from countermanding this and directing the focus specifically on fulfilling research and technology development needs. The second rationale behind this recommendation is the sustained time factor needed to nurture technological expertise. Fixed career-progression trajectories and mandatory rotations of postings are inimical to this. In this regard, it will be informative to see Yang’s model of technology development (shown in Figure 2), which draws attention to the factor of time in technology development and maturation.[31] As is apparent, focused efforts from competent, trained personnel, building upon institutional knowledge iteratively, will be required.

Figure 2: Technology Innovation and Development Trajectory Model

Source: Yang, 2009.[32]

Recommendation 4: Enhance the structure of the ‘Red Force’[c] organisations by involving subject matter experts in advisory roles; further, enhance existing ‘war-gaming’ methods by infusing technology and diverse technical/geopolitical expertise from the civil domain.

Red Force organisations currently comprise only defence officers. While most of them are posted courtesy their tangible competencies, i.e., language specialisation and long tenures at Intelligence Directorates, among other reasons, there is a need to review the charter of ‘Red Force’ and expand the profile of the personnel being posted there. The latter should include experts on relevant subjects according to Recommendation 2. Further, the charter of ‘Red Force’ organisations should expand beyond tactical-level functioning, and include operational and strategic level scenario-building and training, especially for DSSC/equivalent and Higher Command courses. This will need fusion of subject matter experts from geopolitics/area studies (to construct scenarios), service officers (to advise on ‘Red Force’ capabilities), and technicians/engineers (to design complex, war-gaming software).

It will be instructive to note that since 2017, China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has been using complex AI-built scenarios for simulating ‘Blue Force’ actions at tactical and operational levels in complex war-gaming exercises. These exercises have become “less scripted and more demanding.”[33] Further, since 2014, China’s Institute of Command and Control has been conducting national war-gaming exercises across universities to popularise war-gaming among students. In 2017, it conducted the ‘Artificial Intelligence and War-Gaming Nationals’.

During this war-gaming exercise, an AI-system, the CASIA Prophet 1.0, defeated all human teams “by a 7 to 1.22 margin.”[34] This example illustrates the realistic possibility of enhancing current ‘red force’ structures and ‘war-gaming’ methods. The ‘red force’ organisations will need to be supplemented by various civilian SMEs, such as geopolitics and weapons scholars, engineers, and technologists.

Recommendation 5: Leverage civilian expertise to enhance Professional Military Education (PME) for officers going as Defence Attaché (DA)/Assistant DAs, by creating institutional linkages with academic institutions like the School of International Studies (SIS), Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), and Rashtriya Raksha University (RRU) in Gujarat.

The current paradigm of professional military education entails nine to 11-month courses at DSSC in Wellington, Tamil Nadu; the Military Institute of Technology, Pune; and respective War Colleges for Lt Col-equivalent officers of the three armed services, followed by the Higher Command Courses and Higher Defence Management Courses at War Colleges and College of Defence Management, respectively. Given that officers have to delve into various practical nuances of international relations, negotiation tactics, and diplomacy in subsequent appointments (as DAs, ADAs, and UN peacekeeping commanders; as well as in procurement directorates, among other places), there is a need to review the process of conditioning/incubating officers to understand how the nuances of international relations can commence during or after the staff course phase.

Available expertise at both SIS, JNU, and RRU needs to be leveraged so that meritorious officers earmarked for select appointments post-DSSC-phase, or post-HCC-phase can be deputed to these institutions for short courses (one-two months) focused on specific areas of study connected to the region where they will be deputed. Institutional linkages, under the ambit of the DEB, could fructify in the form of MoUs earmarking such short courses on an annual basis, with specific training objectives. Two illustrative examples are shown in Table 3.

Table 3: Leveraging Civil Expertise for Enhancing PME

| Institution | Domain/Area and Duration | Target Audience |

| Centre of Africa Studies, SIS, JNU[35] | Africa Studies: Historical Debates, Contemporary Perspectives, including geopolitics, demography, economics and society. Duration: 3-4 weeks. | DA/NAs/ADAs to African countries |

| Centre for UN Police and Peacekeeping Studies, RRU[36] | Basic and Advanced Certificate Programme for Policing and Peace-Keeping operations Duration: 7-18 days | Officers selected for undertaking UN Peacekeeping (UNPK) Commanders |

Source: As cited; author.

Recommendation 6: Create cutting-edge training aids and infrastructure through robust linkages with the private sector and academia. Subsequently, three futuristic training scenarios are described in Table 4 to illustrate the scope of CMF in empowering the military training institutions to create cutting-edge training aids and infrastructure. Each scenario has been examined, and all micro- and macroscopic factors needed to catalyse such a training environment have been conceptualised. Each case also highlights the kind of civilian assistance required for each case, as well as the potential challenges.

Table 4: Scenarios Illustrating Advanced Training Interventions

| Scenario 1: AI-based Fighter Simulator to simulate aerial human-machine confrontations |

| v In the near future, the emergence of Unmanned Combat Aerial Vehicles (UCAVs) is likely to pose an existential question to the profession of piloting. This author is of the view that the soldierly art of combat piloting cannot ever become obsolete. Pilots will need to be trained to greater competencies, which also involve engaging with UCAVs on AI-based flight simulators. v An AI-based flight simulator will need: · Radar-triangulated data of drone flight patterns · AI-algorithm trained on such data, which trains pilots to progressive complexity based on drone flight patterns and recurrent pilot vulnerabilities/mistakes/weak areas. · Internet connectivity to train and upgrade AI software · Setting up such a simulator will need teams comprising UCAV engineers, graphic designers, AI-engineers, and fighter pilots. v Challenges: Designing a graphics interface, training the AI-module to provide tangible post-training feedback, and incorporating adequate realism in the software. |

| Scenario 2: Mixed Reality (MR) Module to Enhance Equipment Training |

| · Mixed Reality (MR) combines elements of Augmented Reality (AR) and Virtual Reality (VR). MR juxtaposes animations, digital instructions, and abstract concepts with the actual equipment or its replica, and aids trainees to visualise the working mechanisms of the equipment. · MR Modules of critical weapon systems (to train in expeditious defect identification and rectification) will need: v Virtual copies of the equipment surface/parts/components represented in MR setting. This will require specific hardware, such as Microsoft HoloLens, and software, such as Unity and Unreal Engine. v Deciding how users will interact with the MR module, i.e., physical touch, voice commands, or visual cues, among others, which will appropriately address the ‘training need’. v Superlative competencies on the part of engineers, equipment specialists and artists. · Challenges: Integration of different kinds of data; providing access to sensitive/critical equipment, i.e., emerging issues of confidentiality. |

| Scenario 3: E-Learning in Distant Heights |

| · E-learning can be used to ensure ‘anytime, anywhere’ availability of training material. Consider a scenario where an Indian Army Officer peruses the pre-reading material before his upcoming Senior Command Course, while being posted in a high-altitude area. E-learning has the potential to reduce training time by implementing ‘anytime, anywhere’ learning. Theory subjects can be made available online, which trainees can access ahead of the course. On arrival for a course, an exam can be conducted, and thereafter, based on their performance, suitable portions of the curriculum can be covered through class discussions. · The e-learning mechanism will need: v Secure, networked device to maintain OPSEC, i.e., a Graphene-OS powered device. The tab itself maybe embedded with a unique 20-digit International Mobile Subscriber Identity (IMSI). v The device does not connect to SIM networks, but to the military server network/cloud. v Course content is accessed via the MG Sigma Reader app, which can be developed by/at one of the IITs. v The back-end infrastructure runs on hardened LINUX servers located in an Indian city. v Suitable e-learning content, i.e., videos, online quizzes, and presentations accessible via cloud. v This ensures connectivity, robustness, and real-time updates, even in remote areas. Challenges: Generation of content; transition to e-learning methods; and resistance from the user’s end. |

All three training scenarios use the following complex ICT structures:

Scrutinising the above examples yields the following recommendations:

Recommendation 6A: Invest in a Joint Training Cloud which is safe, secure, and indigenously developed in partnership with the National Programme on Technology Enhanced Learning (NPTEL) and IIT on the lines of the Swayam Portal.

At present, the three Services still use optical fibre cables (OFCs) as the primary mode of intra- and inter-Services communication. This overt reliance on OFC has precluded optimum exploitation of the internet, especially in the training domain. This is evident from the fact that while all three Services have their own Learning Management Systems, i.e., MOODLE, their utilisation is governed by inherent systemic limitations. There is a need to harness the power of the internet. However, this would need a secure, hardened system. A Joint Training Cloud via which specific training modules can be administered for each Service, and for joint training initiatives, such as war-gaming, and sharing of study material can be utilised. Based on current national capability, this can be undertaken in partnership with NPTEL and one of the IITs.

Recommendation 6B: Establish an inter-services agency, which could be named, Centre for Armed Forces Training Aid Production (CAFTRAP) under the aegis of Headquarters, Integrated Defence Staff (HQIDS), comprising officers from the armed forces who illustrate creativity in teaching/training, and representatives contracted on project-basis, from civil agencies such as the National Council of Teacher Education (NCTE), the National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT), and the Indian Society of Training and Development (ISTD) to monitor and advise on the design, manufacture, and use of complex training aids for meeting specific training objectives. In addition, the CAFTRAP will also nurture linkages with Indian software development firms like the Centre for Development of Advanced Computing (CDAC), Bhaskaracharya Institute of Space Applications and Geoinformatics (BISAG-N), and Tata Consultancy Services (TCS), and other edtech startups.

The three agencies, i.e., NCTE, NCERT, ISTD, are pioneer institutions in the field of education, training and ‘training the trainers’. Given that training aids such as simulators and AR/VR sets will become more complex over time, and such complexity is commensurate with their training efficacy, there is a need to hone expertise in the domain of training aids production. The potential technology development charters of CAFTRAP are enumerated in the following points.

The following are three illustrative examples of how CAFTRAP will help.

Table 5: Potential Avenues for CAFTRAP

| Domain | Specifics | CMF Opportunities |

| Supply Chain Management | IIM-Kozhikode uses a detailed desktop business simulation to train its managers on Operations and Supply Chain management decision-making.[37] Managers can see the live effects of their decisions, and also the implications of decisions over a period of time.[d] For example, a manager may choose to source a cheaper, lower quality raw material from source A. Initially, this will accrue a marginal increase in profits. However, over time, the sales of the product will fall due to lower quality, thus reducing profits. Something similar can be developed for training Army Supply Corps/Admin and Logistics personnel from the three Services at respective training establishments. | CAFTRAP will coordinate between stakeholders ranging from the Indian Institute of Management, Kozhikode, concerned material/logistics Directorates, and software developers from the private sector. |

| STEM Training at Academies | IITs use numerous platforms like PhET, Geogebra, and animation tools, which help in the creative visualisation of concepts. The same can be implemented at all institutions, training personnel in unclassified STEM subjects. | Service Academies, IITs, and edtech companies |

| War-Gaming | There is a need to upgrade the manner in which war-gaming is conducted. Discussions with edtech professors from IIT-Bombay yielded interesting insights. The entire war-gaming exercise can be undertaken on the metaverse. The SME proposed that the ‘Failure Modes, Effects and Criticality Analysis’ (FMECA) framework can be used within the metaverse to create multi-criteria decision-making environments, thus simulating compelling conflict situations.[38] | Operational Directorates/war-gaming institutions of the Services, IITs, and software developers from private sector enterprises. |

Source: Author’s own

Each of the above scenarios requires the design and generation of complex training aids. An example of a traditional training aid is chalk and the blackboard. The advantage of complex training aids is that one can achieve greater training efficacy by maximising realism. That is why a Mixed Reality (and also Augmented Reality/Virtual Reality) suite of engines will have higher efficacy in training military technicians to undertake Defect Identification and Rectification. The flip side is that conceptualising and designing such systems can be challenging. It is here that CMF can help.

As mentioned earlier, the Indian edtech startup ecosystem has been growing, with many private firms gaining competence in technology-based learning. There is a need to explore options to involve these private sector firms for developing training aids, and further, in training the trainers to develop advanced aids. However, simply ‘contracting’ them and treating them like vendors will lead to suboptimal outcomes. This is because there is an inherent knowledge gap between private-sector firms and military requirements. As previously mentioned, this implies an epistemic gap in understanding between civilian edtech startups that make edtech products catering to generic higher education purposes, and specific training requirements in the armed forces training ecosystem. Table 4 illustrates the latter. Thus, there has to be a closer degree of co-working among the two stakeholders, which will require CMF, between startups, CAFTRAP, and the concerned military-training establishments. The following partnership models can be explored:

Recommendation 7: Introduce greater avenues for Civil and Military Officers to train together and interact. For being feasible and practicable, such avenues need to be concise and interwoven into existing training practices. A few illustrative practices are discussed in the following paragraphs.

Recommendation 8: The CAFTRAP under HQIDS should also be mandated with an administrative charter of duties focusing on intra- and inter-institutional linkages. The following are key illustrative points:

Although there is abundant promise in the CMF domain, there are potential vulnerabilities that need to be considered.

In spite of these challenges, it is also true that warfare in the coming decades will require a ‘whole-of-nation’ approach, given the material, strategic, and tactical complexities involved. Therefore, the reality that militaries have to operate in more complex environments ipso facto implies fostering greater collaboration and cohesion. One must seriously consider how to actualise at least a few of the recommendations in this paper towards preparing Indian personnel for such scenarios by leveraging existing expertise from the academic and civilian domains.

The concept of synchronising different organisations and institutions to achieve strategic advantage has gained relevance in the latter part of the 20th century, given the increasing complexity of warfare attributable to the emergence of paradigm-altering technologies. Thus, in the 1990s, concepts such as ‘next-generation warfare’ and ‘hybrid warfare’ emerged, whose roots can be traced to documents such as ‘Gerasimov Doctrine’[42] and China’s ‘Unrestricted Warfare Doctrine’.[43]

Concepts such as ‘unrestricted warfare’ not only seek to operationalise ‘non-military means’ to counter an adversary’s superiority, but also encompass the entire non-military spectrum, i.e., the “political, economic, technological, ecological, and informational into a shared system of command and control.”[44] It is time that a similar ‘whole-of-nation’ strategy is incorporated in the country’s military training processes.

Ankush Banerjee is a research scholar, and a three-time winner of the United Services Institution Gold Medal Essay Competition. He is a serving officer in the Indian Navy.

The author thanks AVM Arjun Subramaniam (Retd), Rear Admiral SY Shrikhande (Retd), Commodore Amitav Mookherjee, Commodore Edwin Jothirajan, Captain (IN) Gurdeep Bala, and Lieutenant Darshini for their inputs. The author also expresses gratitude to the anonymous reviewers for their feedback.

All views expressed in this publication are solely those of the author, and do not represent the Observer Research Foundation, either in its entirety or its officials and personnel.

[a] RMA refers to advances, predominantly in technology, but also in tactics, strategies, and methods that are dramatically changing the way wars are fought.

[b] The author is trying to connect RMA with the much-needed evolution in the training paradigm. While revolution is a phenomenon which signals a break from previous paradigms, evolution is a slower process that builds upon existing structures.

[c] ‘Red Force organisations’ are military training groups that closely study enemy capabilities, and endeavour to emulate them during war-gaming exercises.

[d] The author had interviewed Prof Kamal Kishore at IIM, Kozhikode. A live demonstration of the simulation was provided.

[1] See Pravin Sawhney, The Last War: How AI Will Shape India’s Final Showdown with China (New Delhi: Aleph, 2022); also see, Andrew Cockburn, Kill-Chain: Drones and the Rise of High Tech Assassins (New York: Verso Books, 2018).

[2] Sujan R. Chinoy, “Tech Wars or Old Battlefields: Lessons from the Recent Conflicts,” Observer Research Foundation, 2024, https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/tech-wars-or-old-battlefields-lessons-from-the-recent-conflicts

[3] Richard Hundley, “Past Revolutions, Future Transformations: What Can History of Revolutions in Military Affairs Tell Us About Transforming the US Military,” RAND Occasional Paper (1999): 9.

[4] Terry C Pierce, War-Fighting and Disruptive Technologies: Disguising Innovation (United Kingdom: Frank Cass, 2004), pp. 34 – 40.

[5] A Krepinevich, “Cavalry to Computer: The Pattern of Military Revolutions,” The National Interest 37, no. 30 (1994): 30-34

[6] On Russia and China are ushering in RMA, see J. Matthew McInnis, “Russia and China Look at the Future of War,” Institute for the Study of War Monograph (2023); for an in-depth, albeit dated appraisal of intelligentisation leading to RMA, see Kapil Kak, “Revolution in Military Affairs: An Appraisal,” Strategic Analysis 24, no.1 (2000); for a generic overview, see, Norman Davis, “An Information-Based Revolution in Military Affairs,” in In Athena’s Camp: Preparing for Conflict in the Information Age, ed. John Arquilla and David Ronfeldt (Virginia: RAND Corporation, 1998), 79-98.

[7]Samuel Huntington, The Soldier and the State: The Theory and Politics of Civil-Military Relations (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1957); Anit Mukherjee, “India’s Civil–Military Relations,” in The Oxford Handbook of Indian Politics, ed. Sumit Ganguly and Eswaran Sridharan (Oxford Academic, 2024), https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198894261.013.35.

[8]Muthiah Alagappa, ed. Coercion and Governance: The Declining Political Role of the Military in Asia (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001); Ayesha Ray, The Soldier and the State: Nuclear Weapons, Counterinsurgency, and the Transformation of Indian Civil-Military Relations (New Delhi: SAGE Publications, 2012); also see Aurel Croissant, Civil-Military Relations in Southeast Asia (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018).

[9]Anit Mukherjee, The Absent Dialogue: Politicians, Bureaucrats, and the Military in India (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020)

[10] Lt Col Akshat Upadhyay, “Civil-Military Fusion for Emerging Technologies in India,” CENJOWS Journal 2, no. 1 (2023), https://cenjows.in/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/9.-Civil-Military-Fusion-for-Emerging-Technologies-in-India-By-Lt-Col-Akshat-Upadhyay.pdf; Sujan Chinoy, “Civil-Military Fusion for Atmanirbhar Bharat,” Observer Research Foundation, https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/civil-military-fusion-for-atmanirbhar-bharat.

[11] “Panel Discussion on ‘Civil-Military Fusion in India’,” MP-IDSA, June 14, 2022, https://www.idsa.in/idsa-event/panel-discussion-on-civil-military-fusion-in-india/.

[12] Richard A. Blitzinger, “Civil-Military Integration and Chinese Military Modernisation,” Asia-Pacific Security Studies 3, no. 9 (2004), https://apcss.org/Publications/APSSS/Civil-MilitaryIntegration.pdf.

[13] See the official website of the United States Army Futures Command: Army Futures Command, “About AFC,” Army Futures Command, https://www.army.mil/futures.

[14] Civil Military Fusion in India, 2022.

[15] Pierce, War-Fighting and Disruptive Technologies: Disguising Innovation.

[16] Stephen Witt, “The Turkish Drone That Changed the Nature of Warfare,” The New Yorker, May 9, 2022.

[17] Group Captain Ashish Thapa, “Civil-Military Fusion in Indian Context,” Centre for Airpower Studies, April 10, 2024, https://capsindia.org/civil-military-fusion-in-the-indian-context/

[18] “Needs Analysis: How to Determine Training Needs,” HR Guide, https://hr-guide.com/Training/Determining_Training_Needs.htm#:~:text=Training%20(a%20performance%20improvement%20tool,indicates%20a%20need%20for%20training.

[19] Allison Rosset, Training Needs Assessment (New Jersey: Education Technology Publications, 1990).

[20] BS Dhanoa, “Military Training in the Times of Social Distancing,” Observer Research Foundation, May 20, 2020, https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/military-training-times-social-distancing-66424

[21] Alka Jain, “From 2016-2023: How the Startup Ecosystem Is Thriving in India despite All Odds? Explained,” Mint, January 18, 2024,

[22] “How Ed-Tech Startups Took Benefit of Pandemic,” Indian Institute of Technology Madras, https://acr.iitm.ac.in/iitm_news_repository/how-ed-tech-startups-took-benefit-of-pandemic/

[23] Saniya Ahmad Khan, “How EdTech Start-Ups Are Transforming the Future of Education,”YourStory, June 6, 2023, https://yourstory.com/2023/06/edtech-startups-transforming-future-education-byjus-physicswallah

[24] Laxman Kumar Behera and Vinay Kaushal, “Estimating India’s Defence Manpower,” MP-IDSA Issue Brief, MP-IDSA, August 4, 2020, https://www.idsa.in/system/files/issuebrief/ib-estimating-indias-defence-manpower-040820.pdf

[25] “Need to Intensify War against Forces Challenging India’s Self-confidence: PM Modi at Naval Seminar,” The New Indian Express, July 19, 2022,

[26] “IIT-Madras Teams with DRDO to Work on Combat Vehicle Technologies,” Indian Institute of Technology Madras, January 3, 2023, https://www.iitm.ac.in/happenings/press-releases-and-coverages/iit-madras-teams-drdo-work-combat-vehicle-technologies

[27] Indian Institute of Management Calcutta, “Advanced Programme in Supply Chain Management,” Indian Institute of Management Calcutta, https://www.iimcal.ac.in/ldp/advanced-programme-supply-chain-management-apscm.

[28] Centre for Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research, https://www.igmpi.ac.in/nanotechnology.

[29] For more details of such Federally Funded Research Centres, see: Department of Defense and Engineering Enterprise, “Federally Funded Research and Development Centers (FFRDC) and University Affiliated Research Centers (UARC),” Department of Defense and Engineering Enterprise,

https://rt.cto.mil/ffrdc-uarc/.

[30] Vivek Gopal, “The Case for Nurturing Military Scientists in the Indian Army,” Occasional Paper No. 320, Observer Research Foundation, June 24, 2021, https://www.orfonline.org/research/the-case-for-nurturing-military-scientists-in-the-indian-army

[31]QP Yang and Rongsheng, “Application Research of Disruptive Innovation in Product Lifecycle” (paper presented during the 16th International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management, August 23, 2009), 713-716.

[32] Yang and Rongsheng, “Application Research of Disruptive Innovation in Product Lifecycle.”

[33] Elsa Kania and Ian Burns McCaslin, “Learning Warfare from the Laboratory: China’s Progression in War-Gaming and Opposing Force Training,” Military Learning and the Future of War Studies (2021),

https://www.understandingwar.org/sites/default/files/Learning%20Warfare%20from%20the%20Laboratory%20ISW%20September%202021%20Report.pdf;For more, see Elsa Kania, “Learning without Fighting: The PLA Prepares for Future Warfare,” Centre for New American Security (2021),

https://jamestown.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Kania_Presentation-1.pdf .

[34]Benjamin Jensen, Christopher Wyte, and Scott Cuomo, “Algorithms at War: The Promise, Peril and Limits of Artificial Intelligence,” International Studies Review (2019): 1-25, https://academic.oup.com/isr/article-abstract/22/3/526/5522301?redirectedFrom=fulltext.

[35] Centre of African Studies, School of International Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, “Centre of African Studies,” Centre of African Studies, School of International Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, https://jnu.ac.in/sis/cas

[36] Rashtriya Raksha University, “Home,” Rashtriya Raksha University, https://rru.ac.in/centre-for-un-police-and-peacekeeping-studies-cunppks/.

[37] Institute of Management Kozhikode, “Business Simulation Lab,” Institute of Management Kozhikode, https://www.iimk.ac.in/business-simulation-lab.

[38] Samyantak Das, “Optimising MCDM Problems Using MSaas in MetaVerse: Reflections on Teaching Learning Strategies Using FMECA as a Framework” (presented during the Southern Naval Command Seminar on Instructional Leadership and Best Instructional Practices, Kochi, February 25, 2025). The authors had detailed discussions with Professor Das about his model and realised the potential of the metaverse to transform the manner in which war-gaming is conducted.

[39] Asian News International (ANI), “Episode 233: The Real Samosa Caucus 4.0. Edition,” YouTube video, 3:01:48 hrs, October 30, 2024, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1kDqwIT-VYw

[40] “IAF, Navy Start Process to Scrap Can Aggregator Deal over Security Fears,” The Times of India (Online), November 8, 2024, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/iaf-navy-start-process-to-scrap-cab-aggregator-deal-over-security-fears/articleshow/115063819.cms

[41] For a full trajectory of discussions on the issue, see the following: Manjeet Negi, “Experts Flag Data Privacy Concerns after Air Force, Uber Sign Pact,” India Today, November 3, 2024, https://www.indiatoday.in/india/story/india-air-force-uber-mou-cab-rides-kgs-dhillion-security-experts-data-privacy-flag-concern-2627369-2024-11-03; Lt Gen DS Hooda (Retd), “Why the Uber-IAF Deal Is Problematic,” The Tribune, November 9, 2024, https://www.tribuneindia.com/news/comment/why-the-uber-iaf-deal-is-problematic/; Lt Gen Prakash Menon (Retd), “Uber Isn’t a Threat to India’s National Security. IAF, Navy Withdrawing MoU Is Overreaction,” The Print, November 19, 2024, https://theprint.in/opinion/uber-isnt-a-threat-to-indias-national-security-iaf-navy-withdrawing-mou-is-overreaction/2361758/.

[42] Martin Murphy, Understanding Russia’s Concept of Total War in Europe, The Heritage Foundation Report, 2016,

https://www.heritage.org/defense/report/understanding-russias-concept-total-war-europe.

[43] Qiao Liang and Wang Xiangsui, Unrestricted Warfare (PLA Literature and Arts Publishing House,1999), https://www.c4i.org/unrestricted.pdf.

[44] SG Chekinov and SA Bogdanov, “The Nature and Content of New-Generation War,” Military Thought (2013):12-23, https://www.usni.org/sites/default/files/inline-files/Chekinov-Bogdanov%20Miltary%20Thought%202013.pdf

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Ankush Banerjee is a research scholar, and a three-time winner of the United Services Institution Gold Medal Essay Competition. He is a serving officer in ...

Read More +