-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

PDF Download

PDF Download

Nilanjan Ghosh, Malancha Chakrabarty, and Swati Prabhu, “The Case for a G20 Development Bank to Resurrect the SDGs,” Issue Brief No. 751, November 2024, Observer Research Foundation.

Introduction

The year 2015 was a landmark year in the history of international development, with the adoption of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)—[a] the first global attempt to set universal goals for all countries and transform the global economic system. The SDGs’ predecessor, the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), were largely focused on the developing and the underdeveloped world. The SDGs were intended to realign the global development pathway with pressing issues in large parts of the developing world, such as environmental degradation, climate change, scarcity of resources, and extreme poverty. However, since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and a series of other crises, progress on SDG implementation has slowed across the globe, including in the wealthiest countries.

The global average SDG index began declining in 2019, at a rate of 0.01 points per year.[1] The pandemic reversed years of progress in poverty eradication, pushing nearly 93 million additional people into extreme poverty.[2] Currently, about one in 10 people worldwide suffer from hunger, and one in three people lack regular access to food.[3] The world is also experiencing the largest number of conflicts since 1946, with nearly a quarter of the world population living in conflict zones.[4]

While high-income countries were able to support their economies through large stimulus packages during the pandemic, developing countries, which lack access to international financial markets and face fiscal constraints, were unable to undertake similar relief measures. On average, high-income countries provided an economic stimulus of about 20 percent of their GDP, whereas economic stimulus in low- and middle-income countries was about 2 percent and 5 percent of GDP, respectively.[5] Moreover, the IMF’s Special Drawing Rights[b] (SDRs) were approved much later in the pandemic, and due to its link to country quotas, African countries and those most in need received only 3 percent of the US$650 billion in SDRs.[6] As a result, unemployment rates declined from 2020 levels in many high-income countries,[7] but most developing countries continued to experience high rates of unemployment;[8] in 2023, the unemployment rate was 4.5 percent in high-income countries and 5.7 percent in low-income countries.[9] In the same year, while the jobs gap[c] rate in high-income countries was 8.2 percent, it was as high as 20.5 percent in the low-income countries.[10]

By 2022, debt levels in low- and middle-income countries were at a 50-year high, and about 60 percent of emerging and developing countries became high-risk debtors.[11] Countries like Zambia, Sri Lanka, Suriname, and Lebanon have already defaulted, and several other countries are at risk of a default.[12],[13],[14],[15] The pandemic also resulted in an increase in wealth inequality, with international poverty and billionaire wealth increasing rapidly post-pandemic.[16] Weaker recovery in developing countries is likely to further exacerbate inter-country inequality.

The developing world has suffered the worst socio-economic impacts of the pandemic and subsequent conflicts. However, even prosperous countries like Denmark, Sweden, and Finland, for example, are not on track to achieve the SDGs.[17] While the Nordic region often leads in global comparisons of SDG achievements, the region is lagging in the achievement of green SDGs, notably SDGs 12,[d] 13,[e] 14,[f] and 15.[g] The region’s overconsumption also makes global sustainability difficult.[18]

Indeed, current trends show that all countries of the world are unlikely to meet the SDGs unless substantial investments are made to reverse the current trends. In the context, this brief argues that finance is the main impediment to SDG implementation. It recommends that, as the pre-eminent global body, the G20 is the ideal platform for the revival of the SDGs. The G20 should create a new financial institution—a G20 development bank—that will fund the implementation of the SDGs, particularly in developing countries.

Finance: The Crucial Barrier to SDGs Implementation

SDG implementation was already slow even before the pandemic, i.e., between 2015 and 2019.[19] While there was broad-based agreement on the global goals, the means of implementation were never free from contention. This is especially true for finance; while developing countries asserted the importance of international assistance, developed countries highlighted the significance of expanding domestic sources of funding and a larger role for the private sector.[20]

As per estimates from the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), the SDG financing gap for developing economies currently stands at US$4 trillion.[21] Table 1 presents the estimated cost and required growth for achieving the SDGs in least developed countries (LDCs) for the 2021-2030 period.

Table 1: Cost and Required Growth for Achieving SDGs in LDCs (2021-2030)

| SDG Targets for 2021-2030 | Required Annual Average Fixed Investments (US$) | Required Annual GDP Growth Rate to Finance Investment |

| SDG Target 8.1: 7% annual GDP growth rate | 462 billion | 7% |

| SDG Target 1.1: Eradicate extreme poverty | 485 billion | At least 9% |

| SDG Target 9.2: Double the share of manufacturing in GDP | 1,051 billion | 20% |

Source: DI (2021),[22] as cited by D’Souza and Jain (2022)[23]

For developing countries, the biggest impediment in the implementation of the SDGs lies in the conceptualisation of SDGs as non-legally binding goals, where the national governments are expected to bear the bulk of the expenses based on their own priorities. Most developing countries lack effective institutional mechanisms and are least capable of gathering the investments required to attain the SDGs. While the flexibility in goal-setting and attainment finds favour with most developing countries, allowing them the policy space to prioritise their own development agenda, it often leads to unbalanced attention to select SDGs, notably SDG 1 (No poverty) and SDG 8 (Economic growth), which is against the basic principles of sustainable development.[24] Additionally, as the ability of governments to raise more domestic resources is related to their ability to fuel economic growth, they tend to focus on prioritising growth over poverty alleviation and redistribution. In other words, to raise domestic resources for SDGs, governments will pursue the conventional growth paradigm, which subordinates environmental concerns for growth, thus defeating the purpose of the SDGs.

As mentioned above, developing countries are currently facing severe challenges related to debt. Between 2020 and 2025, external debt service in developing countries is projected to reach US$375 billion on average—a jump from the US$330 billion average between 2015 and 2019. Compared to 36 percent for all developing countries, 45 percent of the outstanding debt of low-income countries (LICs) will mature by 2024, exposing them to rollover risk.[25] Rising debt burdens, high borrowing costs, and low fiscal space make these countries unable to fund SDGs from domestic resources. According to the Finance for Sustainable Development Report 2023, nearly three quarters of the LDCs and 60 percent of the Small Island Developing States (SIDS) experienced a decline in their tax-to-GDP ratios in 2020.[26] Further, between 2019-2021, unlike in developed countries, tax-to-GDP ratios did not improve in 40 percent of African countries and 36 percent of SIDS and continue to remain at rates lower than pre-pandemic levels.[27]

The prominent form of financing for the MDGs was Official Development Assistance (ODA). However, given the scale of finance required for the SDGs, ODA was regarded as just one of many main sources of finance. While the net ODA flows by Development Assistance Committee (DAC) member countries increased substantially in the aftermath of the pandemic—7-percent increase in real terms in 2000 compared to 2019—it was still much below the target of 0.7 percent of Gross National Income (GNI) at 0.32 percent.[28] Additionally, net bilateral flows to LICs witnessed a decline of 3.5 percent in 2020 compared to 2019.[29]

Private sector investment, leveraged through international support from aid, has often been considered a major source of finance for the SDGs. However, calls for boosting the investment for SDGs in the private sector have not materialised in real terms. Only 4 percent of the US$410 trillion in global private assets is invested in developing economies (including China).[30] Moreover, financing by public development banks, amounting to US$240 billion, is able to mobilise an average of US$44 billion in private investment each year, which constitutes a meagre 1 percent of the climate and SDG investment needs of developing economies.[31]

The failure of the Institutional Financial Architecture (IFA) is a notable concern in the global economic and financial milieu. The IFA is delineated by the collective structures, policies, institutions, and norms that govern the provision of flows of capital and financial services and the oversight of economic stability at the global level. The institutional failures in taking pre-emptive action, the large bureaucratic structures and processes that delay institutional responses to crises, and their ways of viewing development through a Global North lens have led to calls for reforms of the global financial architecture currently epitomised by the IMF, the World Bank, and other multilateral financial institutions.

One of the prevailing criticisms pertains to the failures of these institutions to meet the SDG financing gaps, which also entails climate action financing.[32],[33] The other criticism is related to their structural rigidity and their redundancy in the current context. While these post-Second World War institutions were established with the goal of promoting economic stability and development by providing financial support to countries facing economic crises, this focus has since shifted. The distribution of voting power is skewed in favour of the Global North nations, with a clear underrepresentation of emerging economies of the Global South, raising questions about the diminishing legitimacy of these institutions in an increasingly multipolar world.[34],[35],[36] Joseph Stiglitz, in his work, has long highlighted that the rigidities of the bureaucratic and archaic policies in these organisations leave recipient countries worse off than before.[37]

The 2023 report released by the G20 Eminent Persons Group on Global Financial Governance (EPG) highlighted the failures of the current IFA and provided recommendations for reform.[38] The report emphasises the need for a greater role for the multilateral development banks (MDBs) in financing global public goods such as the SDGs and climate action and also calls for creating a more inclusive and representative global financial governance structure, improving the efficiency and effectiveness of these institutions, and redistributing voting powers to emerging economies like India, China, and Brazil.

A New Paradigm for Global Financial Governance

The present financial institutional system is inadequate, and the call for reforms has become widespread. Any new form of institutional architecture needs to prioritise the needs of the Global South, increase the financing of global public goods such as the SDGs and climate action, and create a more democratic and representative governance structure. The Global Financial Governance report is a step in the right direction, but the implementation will not be easy; it will require strong political will and cooperation from the global community to shake the status quo. Under such circumstances, an institutional platform like the G20 can provide a way out of the impasse that the global financial system has been pushed into.

The G20 is an inclusive and representative system that includes Global North and Global South nations. Successive G20 presidencies of the Global South (especially the double troika of Indonesia-India-Brazil and India-Brazil-South Africa) have highlighted the needs and aspirations of the emerging world. Therefore, while reforms in the existing institution can continue, the G20, with its core principles of inclusivity and addressing crucial global economic concerns like international financial stability, climate change, and sustainable development, is ideally positioned to set up a G20-level development financial institution to meet financing gaps in the global development agenda.

G20 and the SDGs

In 2010, the G20 expanded its agenda by including international development, and in 2015, adopted Agenda 2030, which was aimed at working towards the achievement of the SDGs.[39] While the G20 has served as a forum to manage the world economy, it has largely failed to act as the foremost forum for global development. The G20’s most impressive achievement till date has been its response to the 2008 financial crisis.[h] However, its response to the pandemic has often been criticised;[40] the G20’s efforts to provide debt relief through the Debt Service Suspension Initiative[i] (DSSI) and the Common Framework[j] for debt restructuring provided modest help to developing countries in debt distress after the pandemic. Experts like Dries Lesage have argued that, although the G20 reframed the 2010 Seoul Development Consensus to bring it in line with the SDGs agenda, it did not fully embrace the SDG framework, with the structure of priorities remaining the same as in the G20.[41] Further, he asserts, the G20 mostly invokes the SDGs in the context of developing countries rather than viewing the SDGs as a transformative global agenda.[42] The G20 has played a minimal role in overseeing the achievement of the SDGs within the G20 and the wider world.

The G20 published the G20’s Independent Review of the Multilateral Development Banks’ (MDBs’) Capital Adequacy Frameworks (CAF) in 2022 and launched a G20 Roadmap to accelerate action on MDB governance framework in 2023.[43]

While the 2022 summit in Bali, Indonesia, was dominated by divisions over Russia’s membership in the group and the economic and humanitarian fallout from the war in Ukraine, the focus shifted back to development issues during India’s presidency, with the G20 leaders adopting the G20 2023 Action Plan to promote collective actions to accelerate progress on SDGs through fostering collaboration among G20 work streams and enhancing international partnerships among developing countries, the United Nations, international financial institutions, and other organisations.[44]

As a forum of 19 sovereign countries and the European Union (EU), and now the African Union (AU), the G20 is currently the most influential forum for international cooperation. Not only does the forum comprise the largest economies of the world in terms of trade and GDP, the grouping’s legitimacy has grown immensely with the inclusion of the AU as a permanent member under India’s presidency. The G20 is therefore adequately represented by both the North and the South and is the most appropriate and legitimate institution to carry forward the 2030 Agenda. Currently, Global South countries (India, Brazil, and South Africa) have the agenda-setting role in the G20, and the momentum from India’s presidency can be used to focus on strengthening international cooperation to accelerate SDG implementation.

The G20 should create a development bank to expedite the achievement of the SDGs and address the main barrier to this achievement: finance. Though there may be apprehensions that the G7 will dictate the G20 mandates, this apprehension would be unfounded, as the Global South G20 presidencies have categorically voiced Global South concerns, as witnessed in the G20 New Delhi Leaders’ Declaration.[45]

The Need for a G20 Development Bank

The idea of a separate G20 development bank to fund the SDGs was first proposed in 2023.[46],[47] The Think20 India Communiqué also emphasised the need for a development financial institution under the G20 with the twin objectives of financing the SDG gap and refuelling the growth forces in the event of a crisis.[48] The main reasons behind the need for a G20 development bank are discussed in the following paragraphs.

The current global financial order is not designed to deliver on the sustainable development agenda. Born in the context of the Second World War, the current international financial structure, driven by the MDBs and led by the developed world, does not rightly represent the realities of developing countries.[49] The MDBs are failing to cater to the urgent sustainability challenges of the modern world and are being increasingly criticised for not delivering the results that they promised.

A new development bank to fund the SDGs is necessitated by the fact that efforts to reform the international financial architecture and MDBs is unlikely to yield adequate results. For instance, the World Bank’s main objective of poverty eradication and its country-focused operating model is not aligned with SDG financing, which requires a broader focus across countries and sectors. Several scholars have also expressed their dissatisfaction over current attempts to reform the MDBs.[k],[50]

One of the primary criticisms of the MDBs, World Bank, and the IMF are the power imbalances in their governing structures. Voting shares in the IMF are allocated on the basis of the size and openness of economies. As a result, poor developing countries and borrowing countries are structurally under-represented in the decision-making process.[51] In the World Bank, votes are determined by financial contributions and size.[52] Although voting powers in the World Bank were revised in 2010,[l] the G7 countries and China continue to have the greatest voting power.[53] As the largest shareholder of the World Bank (about 16 percent), the US has veto power over certain World Bank decisions, whereas countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, which are the main stakeholders of the Bank, together have less than 6 percent of the votes and exercise little influence over the Bank’s operations.[54] The so-called ‘gentlemen’s agreement’[m] between the US and the European countries also ensures that the Bank and the IMF are always headed by a US and European national, respectively.

Several scholars have argued that, although the World Bank and the IMF are structured as financial institutions, their governance systems are not like actual financial institutions. Their shareholders, which are individual countries, are motivated by advancing their own geopolitical interests,[55] and the competing interests of powerful shareholders often lead to a neglect of the interests of smaller, developing countries.

The international financial structure has failed to act as a global safety net for the developing countries and is inherently unjust. At the 2023 Paris Summit for the New Global Financing Pact,[n] United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres called the international financial architecture “outmoded” and “dysfunctional” and accused it of exacerbating poverty and inequality.[56] Not only was the allocation of SDRs between high- and low-income countries inequitable, “the high-income countries were also able to print money to revive their economies in the aftermath of the pandemic, while developing countries struggled with very high borrowing costs (up to nearly eight times higher than the developed countries)”[57] and continue to pay more on debt service than on healthcare and education needs of their populations.

International financial institutions typically prioritise the economic rate of return[o] at the expense of environmental and climate concerns. The Bretton Woods Institutions have lagged in measures to protect the environment and address climate change. Despite mixed evidence of the link between growth and poverty alleviation,[58],[59] both the World Bank and the IMF have pushed for a growth-based approach to poverty alleviation at the expense of environmental degradation, thereby intensifying the climate crisis. Most attempts by the institutions to address climate change and environmental degradation have been limited to integrating these concerns into the growth-based model itself.[60] Therefore, the basic tenets of these institutions are not in line with Agenda 2030, which calls for systemic changes in the global economy rather than the pursuit of economic growth.

Additionally, the World Bank and other MFIs have not aligned its lending portfolio with the Paris Agreement. Although the World Bank contributes a significant share of project finance towards renewable energy development, its overall influence is not in line with low carbon development. It continues to fund fossil-fuel projects and thereby contributes to higher profit margins for oil, gas, and coal operations.[61] So far, the World Bank has not developed a framework to assess the climate impacts of its Development Policy Finance[p] (DPF). Additionally, climate concerns were found not to feature prominently in the emergency response funding channelled by the DPF in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic.[62]

The record in climate adaptation finance is also disappointing. UNEP’s 2023 Adaptation Gap Report[63] reveals that the chasm between the demand for climate adaptation finance and the provision of actual funds is not only widening but has moved to a staggering 10-18-fold difference. Between 2020 and 2030, the amount needed to adapt against climate impacts in developing countries stands at a hefty US$215 billion annually, with the funding requirements to implement domestic adaptation blueprints reaching US$387 billion each year.[64] Despite the urgent call to action, public multilateral and bilateral adaptation finance coffers witnessed a 15-percent dip in 2021, dwindling to a mere US$21 billion. Consequently, the adaptation finance chasm has widened even more, ranging from US$194 to US$366 billion annually.[65] MFIs and DFIs have revealed a lopsided financing portfolio with significant funding biases in favour of mitigation projects.[66] This is because of perceptible returns on investment (RoI) associated with energy transition projects, as compared to adaptation projects where RoIs are imperceptible and often result in the creation of public goods.[67]

While the current MDBs were founded in response to the challenges faced by a post-war world 70 years ago, the urgency of today’s challenges calls for a more robust and effective multilateral response. Current global challenges cannot be treated in an incremental manner by modifying existing institutions. Bold and systemic changes are the need of the hour. It is clear that the SDGs can only be implemented through new, stable, and long-term sources of funding. Given the limitations of the current financial order and the gap in SDG financing, a creative approach to mobilising finance is the only way forward. Even as finance is the main impediment to SDG implementation, there is no shortage of funds globally. However, the funds do not flow to regions and sectors that need it the most.

As an innovative financing instrument, the G20 development bank will strategise and enhance collaborative efforts for supporting sustainable financing within the G20, specially for the Global South. The G20’s own financial institution should combine the best features of North-South and South-South cooperation models;[68] while the North is preferred for its norms and standards, the South is more capable of identifying the financial deficits faced by developing countries.[69]

Moreover, experience from the last two decades shows that there is a need to safeguard the SDGs in the face of global shocks. A new development finance institution (DFI) will be instrumental in reinforcing South-South cooperation and South-North partnerships, with Global North expertise helping design Global South financing mechanisms. A single organising body will also ensure that geopolitical conditions do not blind the process of forwarding aid to less developed countries.[70]

The G20 Development Bank: Objectives, Nature, and Structure

The primary objective of the recommended G20 development bank is furthering the implementation of the SDGs at an accelerated pace, particularly in developing countries. The establishment of a G20 development bank will be an important step in the 2023 Action Plan. Moreover, it will be a concrete step towards SDG implementation by the G20. The establishment of a G20 development bank to fund the sustainable development agenda will also address the finance gap in Agenda 2030. A G20 development bank can also ensure that the process of making sustainable development financing accessible to less developed nations is not hindered by geopolitical or other disruptions. Further, the G20 development bank would improve global liquidity and provide long-term funds for sustainable projects. Unlike regional development banks like the Asian Development Bank and the African Development Bank, the G20 development bank will not have a regional focus.

The priorities of the G20 development bank should be different from those of the existing MDBs, which exacerbate global inequalities. Unlike other MDBs, the G20 development bank should provide financing to developing countries on fair terms. Additionally, the G20 development bank should incorporate climate change and other environmental concerns such as biodiversity loss in its operations to better reflect the true benefits and costs of every project and maximise the social rate of return.[q] Focusing on long-term social rates of return will be particularly beneficial for climate-adaptation projects in developing countries, which are typically overlooked by traditional financial institutions due to their poor short-term returns.

All G20 members (including the EU and the AU) will be members of the G20 development bank. The shareholders will be represented by the bank’s board of governors, comprising the member countries’ finance ministers.

The institutional responsibilities of the bank will be as follows:

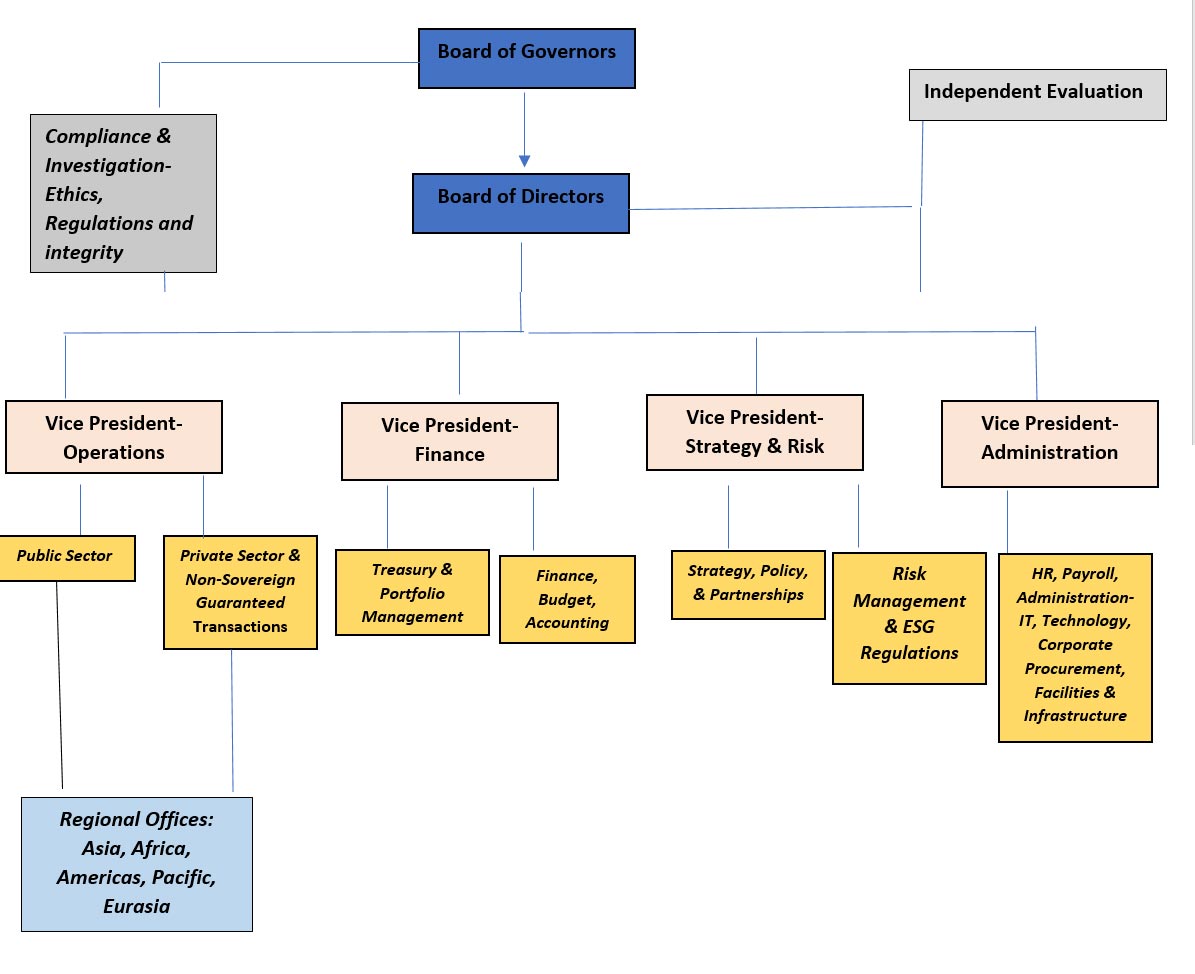

The G20 development bank secretariat will be composed of several divisions and offices, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: The Structure of the G20 Development Bank

Source: Authors’ own

The priority of the bank will be to fund sustainable development projects that accelerate inclusive growth and are aimed at improving the lives of people in developing countries. The purpose is also to support projects in both the public and private sectors through equity in investments, loans, and other appropriate tailored instruments. There is also a strong focus on collaboration between civil society, philanthropy, local communities, international organisations, and other relevant development partners. The areas of operation are as follows:

Conclusion

The adoption of the SDGs marked a historical moment, highlighting common goals for developed and developing nations. However, the means of implementation, particularly mobilising finance, have proven to be a massive challenge because the current global financial order is not designed to deliver on the ambitious sustainable development agenda. The COVID-19 pandemic and a series of subsequent shocks have made the SDGs even more difficult to achieve. MDBs are failing to cater to the urgent sustainability challenges of the modern world and are increasingly being criticised for not delivering the results that they promised. In this context, the G20 would be the ideal platform to reinvigorate the SDG agenda by addressing the widening SDG financing gap.

One could also argue that some of Global South financial institutions, such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the New Development Bank (NDB), could also be equipped to respond to the needs and aspirations of the Global South. This may raise questions about the need for a G20-level development bank. The need for a G20 development financial institution remains crucial for three reasons. First, the AIIB is a China-driven institution that is furthering their own expansionist agenda of the Belt and Road Initiative. Additionally, the AIIB has a skewed power structure and cannot be perceived as an equitable, inclusive, and democratic institution. Second, the NDB is yet to address the need for adaptation finance, and its global nature is still under question. Third, the G20 DFI emphasises the need for collaborative North-South engagement, drawing funds from the North and transferring it to the South. With the South bearing the brunt of the North’s growth ambitions, the imperative is an institution that ensures Global North-South transfer to meet the development needs and ambitions of the South. This mechanism of the G20 development bank is an attempt to be inclusive, equitable, and non-Western and ensure that the concerns of the South can be addressed by the North.

The creation of such a DFI is further necessitated by the fact that efforts to reform the international financial architecture and MDBs are unlikely to yield adequate results and mobilise requisite resources. A G20 development bank will be instrumental in funding sustainable development projects that accelerate inclusive growth to improve the lives of people in developing countries and supporting projects in both public and private sectors through equity in investments, loans, and other appropriate tailored instruments.

Endnotes

[a] A package of 17 aspirational goals including targets to completely eliminate hunger and poverty, tackling climate change, halting the loss of biodiversity and degradation of ecosystems, promoting access to healthcare and education, and reducing inequalities.

[b] The SDR is an international reserve asset. Its value is linked to a basket of currencies: the US dollar, the euro, the Japanese yen, the Chinese renminbi, and the British pound sterling.

[c] ‘Jobs gap’ is an indicator developed by the International Labour Organization that measures labour underutilisation beyond unemployment. To be considered unemployed, jobless persons have to be available to take up employment at a very short notice and have to be actively searching for a job. Many people in developing countries, particularly women, fail to meet the strict criteria but have an unmet need for a job. Therefore, this indicator is an important complement to unemployment rate.

[d] Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns, which is key to sustain the livelihoods of current and future generations.

[e] Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts.

[f] Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas, and marine resources for sustainable development.

[g] Protect, restore, and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, halt and reverse land degradation, and halt biodiversity loss.

[h] In response to the financial crisis of 2008, the G20 leaders met at the heads of state level in Washington and emerged as the principal forum for international response to the financial crisis. The Washington Declaration called for strengthening of prudential and financial norms and a series of measures like stronger capital requirements and changes in international accounting standards.

[i] In 2020, the G20 announced the Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) under which bilateral official creditors suspend debt service payments from the least developed countries upon request.

[j] The G20 Common Framework was announced in November 2020 to deal with the unsustainable debt of developing countries beyond the DSSI.

[k] For instance, Ghanem has argued that significant capital infusion is required for the World Bank to increase its financing of global public goods, which is unlikely to succeed because most governments are facing budgetary issues. See: Ghanem, “The World Needs a Green Bank”.

[l] In 2010, the voting power of developing and transition countries (DTC) at IBRD and IFC increased, bringing their voting share to 47.19% and 39.8%, respectively.

[m] Europe and United States have a ‘gentlemen’s agreement’ that the World Bank would be led by an American while the IMF would be led by a European.

[n] The Paris Summit for a New Global Financing Pact was held on 22nd and 23rd June 2023. Nearly 40 heads of states and leaders of international and regional organisations, presidents of development banks, civil society organisations, and private sector companies participated in the conference. The summit called for accelerated actions for SDGs and led to the declaration of the Paris Pact for People and Planet.

[o] The economic rate of return is a metric which shows the how a project’s economic benefits compare to its costs. The economic rate of return indicates efficiency of resource use when prices are adjusted to reflect relative economic scarcities.

[p] Development Policy Finance is a World Bank lending instrument which provides funds to a borrowing country via non-earmarked budget support. Unlike other instruments like Investment Project Financing and Program-for-Results, it is not earmarked for specific projects but supports policy reforms and direct budget support. It is issued by the IDA and the IBRD.

[q] Social return on investment (SROI) is a method for measuring values that are not traditionally reflected in financial statements, including social, economic, and environmental factors. They can identify how effectively a company uses its capital and other resources to create value for the community.

[1] Jeffrey D. Sachs et al., Sustainable Development Report 2022 – From Crisis to Sustainable Development: the SDGs as Roadmap to 2030 and Beyond, United Kingdom, Cambridge University Press, 2022, https://s3.amazonaws.com/sustainabledevelopment.report/2022/2022-sustainable-development-report.pdf

[2] UN-DESA, The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2022, July 2022, New York, United Nations – Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2022, https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2022/The-Sustainable-Development-Goals-Report-2022.pdf

[3] “The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2022, July 2022”

[4] United Nations, “With Highest Number of Violent Conflicts Since Second World War, United Nations Must Rethink Efforts to Achieve, Sustain Peace, Speakers Tell Security Council,” January 26, 2023, https://press.un.org/en/2023/sc15184.doc.htm

[5] Brahima Sangafowa Coulibaly, “Rebooting Global Cooperation is Imperative to Successfully Navigate the Multitude of Shocks Facing the Global Economy,” Brookings, September 16, 2022, https://www.brookings.edu/essay/rebooting-global-cooperation-is-imperative-to-successfully-navigate-the-multitude-of-shocks-facing-the-global-economy/

[6] Coulibaly, “Rebooting Global Cooperation is Imperative to Successfully Navigate the Multitude of Shocks Facing the Global Economy”

[7] ILO, World Employment and Social Outlook: Trends 2024, January 2024, Geneva, International Labour Organization, 2024, https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/wcmsp5/groups/public/%40dgreports/%40inst/documents/publication/wcms_908142.pdf

[8] “World Employment and Social Outlook: Trends 2024, January 2024”

[9] “World Employment and Social Outlook Trends: 2024, January 2024”

[10] “World Employment and Social Outlook Trends: 2024, January 2024”

[11] Jose Antonio Ocampo, “A Pandemic of Debt,” Project Syndicate, December 12, 2022, https://www.project-syndicate.org/magazine/debt-crisis-default-relief-world-bank-imf-by-jose-antonio-ocampo-2022-12

[12] Martin Kessler, “The Road to Zambia’s 2020 Default,” Finance for Development Lab, December 6, 2023, https://findevlab.org/the-road-to-zambias-2020-sovereign-debt-default/

[13] Indrajit Coomaraswamy and Ganeshan Wignaraja, “What Can We Learn from Sri Lanka’s Debt Default?,” London School of Economics, October 16, 2023, https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/southasia/2023/10/16/what-can-we-learn-from-sri-lankas-debt-default/

[14] “For the First Time, Lebanon Defaults on its Debts,” The Economist, March 12, 2020, https://www.economist.com/middle-east-and-africa/2020/03/12/for-the-first-time-lebanon-defaults-on-its-debts

[15] Daniel Munevar, “Dam Debt: Understanding the Dynamics of Suriname’s Debt Crisis,” Eurodad, January 20, 2021, https://www.eurodad.org/dam_debt_suriname

[16] Francisco HG Ferriera, “Inequality in the Time of COVID-19,” Finance & Development and International Monetary Fund, June 2021, https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2021/06/pdf/inequality-and-covid-19-ferreira.pdf

[17] Jeffrey D. Sachs et al., “Sustainable Development Report 2022 – From Crisis to Sustainable Development: the SDGs as Roadmap to 2030 and Beyond”.

[18] “Nordic Consumption Must Change if SDGs are to be Achieved,” Nordic Co-operation, February 2, 2023, https://www.norden.org/en/news/nordic-consumption-must-change-if-sdgs-are-be-achieved

[19] Sustainable Development Report, “Executive Summary of Key Findings and Recommendations,” https://dashboards.sdgindex.org/chapters/executive-summary

[20] Mark Elder et al., “An Optimistic Analysis of the Means of Implementation for Sustainable Development Goals: Thinking about Goals as Means,” Sustainability 8, no. 9 (2016): 962, https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/8/9/962

[21] United Nations, “Developing Countries Face $4 Trillion Investment Gap in SDGs,” July 5, 2023, https://news.un.org/en/story/2023/07/1138352

[22] UNCTAD, “Reversing the Trends that Leave LDCs Behind,” September 23, 2022.

[23] Renita D’Souza and Shruti Jain, “Bridging the SDGs Financing Gap in Least Developed Countries: A Roadmap for the G20,” Observer Research Foundation, October 2022.

[24] Oana Forestier and Rakhyun E Kim, “Cherry-Picking the Sustainable Development Goals: Goal Prioritization by National Governments and Implications for Global Governance,” Sustainable Development 28, no. 5, September 2020: 1019-1518, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/sd.2082

[25] “Global Outlook on Financing for Sustainable Development Goals 2023,” OECD Ilibrary, November 10, 2022, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/fcbe6ce9-en/index.html?itemId=/content/publication/fcbe6ce9-en

[26] UN- DESA, Financing for Sustainable Development Report 2023: Inter-Agency Task Force on Financing for Development, April 2023, New York, United Nations- Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2023.

[27] “Financing for Sustainable Development Report 2023: Inter-Agency Task Force on Financing for Development, 2023”

[28] UN-DESA, Strengthen the Means of Implementation and Revitalize the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development, United Nations-Department of Economic and Social Affairs, https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2021/goal-17/

[29] “Strengthen the Means of Implementation and Revitalize the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development”

[30] Christopher Clubb, “A Blueprint for Closing the SDG Financing Gap: How to Raise $290 Billion in 12 Months to Tackle the World’s Biggest Problems,” Convergence, April 27, 2023, https://www.convergence.finance/news-and-events/news/5eAYctFCu0NeHdy3aaMsc4/view

[31] Clubb, “A Blueprint for Closing the SDG Financing Gap: How to Raise $290 Billion in 12 Months to Tackle the World’s Biggest Problems”

[32] United Nations, “Global Financial Architecture Has Failed Mission to Provide Developing Countries with Safety Net, Secretary-General Tells Summit, Calling for Urgent Reforms,” June 22, 2023, https://press.un.org/en/2023/sgsm21855.doc.htm

[33] Abel Gwaindepi and Amin Karimu, “Reform of the Global Financial Architecture in Response to Global Challenges. How to Restore Debt Sustainability and Achieve SDGs?,” European Parliament, June 2024, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/IDAN/2024/754451/EXPO_IDA(2024)754451_EN.pdf.

[34] Rob Clark, “Quotas Operandi: Examining the Distribution of Voting Power at the IMF and World Bank,” The Sociological Quarterly 58, no. 4 (2017): 595–621, https://doi.org/10.1080/00380253.2017.1354735

[35] Trung A Dang and Randall W Stone, “Multinational Banks and IMF Conditionality,” International Studies Quarterly 65, no. 2 (2021): 375-386, https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqab010

[36] Tyler Pratt, “Angling for Influence: Institutional Proliferation in Development Banking,” International Studies Quarterly 65, no. 1 (2021): 95-108, https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqaa085.

[37] Joseph Stiglitz, Globalisation and its Discontents (Penguin Publishers, 2002).

[38] Global Financial Governance, Report of the G20 Eminent Persons Group on Global Financial Governance (EPG), G20 Eminent Persons Group on Global Financial Governance, 2023, https://www.globalfinancialgovernance.org/report-of-the-g20-epg-on-gfg/overview/

[39] G20 India, “G20-Background Brief,” https://www.g20.in/en/docs/2022/G20_Background_Brief.pdf.

[40] James McBride et al., “What Does the G20 Do?,” Council on Foreign Relations, https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/what-does-g20-do

[41] Dries Lesage, “The Multiple Roles of the G20 with Regard to the UN Sustainable Development Goals,” in The G20, Development and the UN Agenda 2030, ed. Dries Lesage and Jan Wouters (London: Routledge, 2022)

[42] Lesage, The Multiple Roles of the G20 with Regard to the UN Sustainable Development Goals

[43] “G20 Roadmap for the Implementation of the Recommendations of the G20 Independent Review of Multilateral Development Banks,” Capital Adequacy Frameworks, July 2023, https://cdn.gihub.org/umbraco/media/5355/g20_roadmap_for_mdbcaf.pdf

[44] G20 Informative Centre, “G20 2023 Action Plan on Accelerating Progress on the SDGs,” June 12, 2023, http://www.g20.utoronto.ca/2023/230612-sdg-action-plan.html

[45] “G20 New Delhi Leaders’ Declaration,” https://www.mea.gov.in/Images/CPV/G20-New-Delhi-Leaders-Declaration.pdf.

[46] Nilanjan Ghosh and Soumya Bhowmick, “Bridging the SDGs Financing Gap: A Ten-Point Agenda for the G20,” T20 India Policy Brief, 2023, https://t20ind.org/research/bridging-the-sdgs-financing-gap-a-ten-point-agenda-for-the-g20/#_edn7

[47] Swati Prabhu and Nilanjan Ghosh, “Increasing Cooperation for Sustainable Development: Imperatives for India’s G20 Presidency,” Observer Research Foundation, June 2023.

[48] “Think 20 India Communiqué,” Think20 India Communiqué | ThinkTwenty (T20) India 2023 - Official Engagement Group of G20 (t20ind.org)

[49] “Multilateral Development Banking for this Century’s Development Challenges: Five Recommendations to Shareholders of the Old and New Multilateral Development Banks,” Centre for Global Development, 2016, https://www.cgdev.org/publication/multilateral-development-banking-for-this-centurys-development-challenges

[50] Hafez Ghanem, “The World Needs a Green Bank,” Policy Center for the New South, February 2023.

[51]“What are the Main Criticisms of the World Bank and the IMF?,” Bretton Woods Project, June 4, 2019, https://www.brettonwoodsproject.org/2019/06/what-are-the-main-criticisms-of-the-world-bank-and-the-imf/ https://www.brettonwoodsproject.org/2019/06/what-are-the-main-criticisms-of-the-world-bank-and-the-imf/

[52] World Bank Group, “Voting Powers,” https://www.worldbank.org/en/about/leadership/votingpowers#:~:text=Allocation%20of%20Votes%20by%20Organization&text=Each%20member%20receives%20votes%20consisting,share%20votes%20for%20all%20members).

[53] World Bank, “International Bank for Reconstruction and Development Subscriptions and Voting Power of Member Countries,” https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/795101541106471736-0330022021/original/IBRDCountryVotingTable.pdf

[54] Owen Barder, “Time, Gentlemen, Please,” Centre for Global Development, February 6, 2019, https://www.cgdev.org/blog/time-gentlemen-please#:~:text=Since%20the%20Second%20World%20War,be%20led%20by%20a%20European.

[55] Jennifer Nordquist and Dan Katz, “The World Bank and the International Monetary Fund Should Do Less to Achieve More,” Centre for Strategic and International Studies, January 22, 2024, https://www.csis.org/analysis/world-bank-and-international-monetary-fund-should-do-less-achieve-more#:~:text=Although%20the%20World%20Bank%20and,mechanism%20of%20the%20profit%20motive.

[56] Unted Nations, “Global Financial Architecture Has Failed Mission to Provide Developing Countries with Safety Net, Secretary-General Tells Summit, Calling for Urgent Reforms,” June 22, 2023, https://press.un.org/en/2023/sgsm21855.doc.htm

[57] United Nations, “Global Financial Architecture Has Failed Mission to Provide Developing Countries with Safety Net, Secretary-General Tells Summit, Calling for Urgent Reforms”

[58] Richard H. Adams, Economic Growth, Inequality, and Poverty: Findings from a New Data Set, Washington DC, World Bank Group, 2003, http://hdl.handle.net/10986/19109 License: CC BY 3.0 IGO.

[59] Beatriz Pérez de la Fuente, Economic Growth and Poverty Reduction in a Rapidly Changing World, European Commission, 2016, https://economy-finance.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2022-07/eb019_en.pdf.

[60] Bretton Woods Project, “What are the Main Criticisms of the World Bank and the IMF?”

[61] Heike Mainhardt, “World Bank Group Financial Flows Undermine the Paris Climate Agreement: The WBG Contributes to Higher Profit Margins for Oil, Gas, and Coal,” Urgewald, https://www.urgewald.org/sites/default/files/World_Bank_Fossil_Projects_WEB2.pdf

[62] Lauren Sidner and Elisha George, “NSIDER: The World Bank’s Policy Lending Can Better Support Climate Action,” World Resources Institute, October 7, 2020, https://www.wri.org/technical-perspectives/insider-world-banks-policy-lending-can-better-support-climate-action

[63] UNEP, Adaptation Gap Report 2023: Underfinanced. Underprepared. Inadequate investment and planning on climate adaptation leaves world exposed, Nairobi, United Nations Environment Programme, 2023, https://doi. org/10.59117/20.500.11822/43796.

[64] “Adaptation Gap Report 2023: Underfinanced. Underprepared. Inadequate Investment and Planning on Climate Adaptation Leaves World Exposed, 2023”

[65] “Adaptation Gap Report 2023: Underfinanced. Underprepared. Inadequate Investment and Planning on Climate Adaptation Leaves World Exposed, 2023”

[66] Nilanjan Ghosh, “Adaptation Finance for the Global South: Imperatives for a new EU-India Climate Partnership,” in International Cooperation on Climate Change: Insights from South and Southeast Asia and the EU, ed. Thomas Leeb, Michelle Wiesner, and Laura Lahner (Brussels: Hans Seidel Stiftung, 2024), https://europe.hss.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Projects_HSS/Europe/Dokumente/IIZ/International_cooperation_on_climate_change_HSS.pdf

[67] Ghosh, “Adaptation Finance for the Global South: Imperatives for a New EU-India Climate Partnership”.

[68] Prabhu and Ghosh, “Increasing Cooperation for Sustainable Development: Imperatives for India’s G20 Presidency”

[69] Prabhu and Ghosh, “Increasing Cooperation for Sustainable Development: Imperatives for India’s G20 Presidency”

[70] Ghosh and Bhowmick, “Bridging the SDGs Financing Gap: A Ten-Point Agenda for the G20”

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Dr Nilanjan Ghosh is Vice President – Development Studies at the Observer Research Foundation (ORF) in India, and is also in charge of the Foundation’s ...

Read More +

Dr Malancha Chakrabarty is Senior Fellow and Deputy Director (Research) at the Observer Research Foundation where she coordinates the research centre Centre for New Economic ...

Read More +

Dr Swati Prabhu is Associate Fellow with the Centre for New Economic Diplomacy at the Observer Research Foundation. Her research explores the interlinkages between development ...

Read More +