Introduction

The ways of diplomacy are dynamic, and over the years, new forms, methods, techniques and rules of protocol, have emerged in the domain. What is known as ‘classic diplomacy’ until the First World War was predominantly bilateral in nature; it would eventually give way to new kinds. In the 1910s, then United States (US) President Woodrow Wilson argued against “closed diplomacy” that involved secrecy in negotiations and agreements. In his famous ‘14 Point Peace Plan’, which became the ideological basis for the establishment of the League of Nations, Wilson had emphasised the merit and imperative of “open covenants openly arrived at.”[1]

Over time, even as the bilateral framework of diplomacy was retained, modern diplomacy took centrestage, often involving multiple concerns, parties, and methods. Diplomacy increasingly became multilateral. In today’s interdependent and globalised world, summit meetings and the high table of what is called ‘summit diplomacy’ allows different stakeholders to interact, exchange viewpoints, sort out divergences, and work for mutually agreeable standpoints.

While summit diplomacy is not a new concept, it now plays a significant role in international relations. According to Jan Melissen, Professor of Diplomatic Studies, “It’s an old practice which has acquired a new dimension due to the peculiarities of the world in which we live in.”[2] The development of summit diplomacy in the 20th century has had a significant impact on the way in which dialogues between nation states are conducted.[3] Today the term ‘summit’ has become an integral part of the political and diplomatic lexicon. The advent of globalisation has allowed the development of a transport network that allows delegates to travel from one part of the world to another in a short period of time. More importantly, current global issues increasingly require a global approach.[4]

There are two elements common to all definitions of what constitutes a ‘summit’: diplomatic participation of heads of states and/or government and of high representatives of international organisations, and personal contact between leaders.

As a form of dialogue between states, summitry has distinct diplomatic functions. The flexibility of summits provides educational value to leaders who may be lacking in international experience. Apart from the opportunity to become familiar with their peers, summits are also ideal for private consultations. This would bypass multiple bureaucratic layers and may take place at any stage of international negotiations. As International Studies lecturer, Professor David H. Dunn surmises, the impact of communications technology and the process of democratisation and decolonisation have “significantly influenced the development of summitry in the post-war period as a significant diplomatic institution.”[5]

The rest of this paper delves into the evolution of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC), established in 2000. It highlights the shifting priorities and move away from infrastructure-centric and loan-heavy approach of the previous years to a greater emphasis on trade promotion and facilitation. It ponders the motives that explain why African countries and its leaders are engaging in summit diplomacy, and underlines the uneven relationship between these countries and China.

Africa’s Experience with Summitry

The role of summits in the international relations of post-colonial Africa can be examined within a context dominated by various factors—including the very process of decolonisation. As African countries began attaining independence, formal powers and institutions were transferred from the European colonial powers to the African states. In almost all the cases, the power and ability of sovereign African states to control and conduct their foreign relations was the last issue to get addressed.[6] Therefore, the newly independent states of Africa had to redraw their foreign relations.

The second factor was the lack of sufficiently trained diplomats. Appointments were based generally on patronage and on these candidates’ support to the new political dispensation. Appointments would be sometimes used as “rewards”, and at others as a strategic way of removing political opponents. The practice would strengthen the hand of executive presidents and if there arose any difficulty or opposition to the preference of the government, the diplomats would be conveniently removed.

Political scientist Richard Hodder-Williams has noted how most of the newly independent states of Africa lacked clear goals in the area of foreign relations. They had inherited borders and were keen to make their independence work. However, “little thought was given to specific policies even in these areas which (is) hardly surprising given the nature of African nationalism.”[7] Arguments favouring alignment or non-alignment divided the leadership in some countries. However, the debates hardly resonated with the aspirations of the larger African populations, and foreign-policymaking was the exclusive domain of the executive.

Newly independent countries were determined to express their sovereign powers. Often this would necessitate issuing proactive statements. The idea was to show some discontinuation from the past, assert sovereign rights, and introduce new initiatives in government’s roles and diplomatic relations.

Lastly, there was also a determination to take initiatives in locating Africa’s position within the world. More immediately, as Colin Legum, a South African author on African politics argued in 1961, African countries “were determined to find African solutions to African problems, to show that political leaders could be statesmen in resolving continental conflicts, and to move forward the pan-African ideals which were of vital importance during the movement towards independence.”[8]

This is the context in which the new states of Africa began their conduct of international relations. There was no continent-wide organisation to mediate between the states, especially between the Anglophones and the Francophones. There were also no long-established channels of diplomatic communications, and ad-hoc meetings between heads of governments was the most viable means. All this made summitry in an African context inevitable.[9]

The constitutions which Britain and France bequeathed to African countries were highly centralised ones. Power was concentrated in systems, whether the presidential model (of France) or parliamentary (of Great Britain). Governments were formed which were highly authoritarian. Then there were governments that were consensual but where the leader dominated policymaking. M. Tamarkin, a noted biographer (1990) observed that although government leaders exercised huge powers in the field of foreign affairs, African states acting individually have carried little weight.[10] Therefore, African leaders tended to put their support and weight to organisations that would emphasise equality of states, irrespective of population size, or economic and military strength. Since the United Nations was based on the principle of “sovereign equality of member states”, African leaders regarded it as a forum where African views could be expressed. Moreover, through the voting system in the UN, great powers may be prevented from acting unilaterally in matters of international and global significance. Other post-colonial states may join the African countries and overcome their individual weaknesses to realise a sense of collective influence.

African member countries of the Commonwealth used the annual heads of government meetings to voice their developmental concerns to their former colonial governments. It could be said that in effect, these were summits. A large number of African countries in such international forums could ensure that their point of view was at least heard, even if not always accepted. Attendance in summit meetings and performance therein thus became central to the foreign policy of the African countries. As Williams noted, summits became essential resources for political leaders in the continent for multiple reasons: “the status and aspirations of leaders, the need for collective action, the psychological attachment to the pan-African ideals, and the lack of alternative and developed structures for exerting influence.”[11] Summits enabled the continent’s leaders to coordinate their activities at international gatherings such as the UN, the UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), and the Organisation of African Unity (OAU), later changed to African Union.

Role of Major Powers

Global powers have been engaging with African countries through summits for many years. France was the first to engage with the continent in the form of summits as early as in the 1970s. Subsequently, various other global players have engaged with African nations at both bilateral and multilateral levels. The creation of the International Organisation of La Francophonie, representing a group of countries or regions where French is the first or customary language, paved the way for engagement between France and the African countries. By enabling the heads of state and government to hold a dialogue on current international issues, the summit served to define the policies and goals of ‘La Francophonie’. The first Francophonie Summit was held in Versailles in 1986. Since then, France and Africa’s ties have grown manifold to include diverse fields of engagement and cooperation such as democratic governance, peace and security, energy security, and counterterrorism. Other powers including the US, India, Turkey, the UK, Japan, Brazil, and Germany have also engaged with Africa through summits.

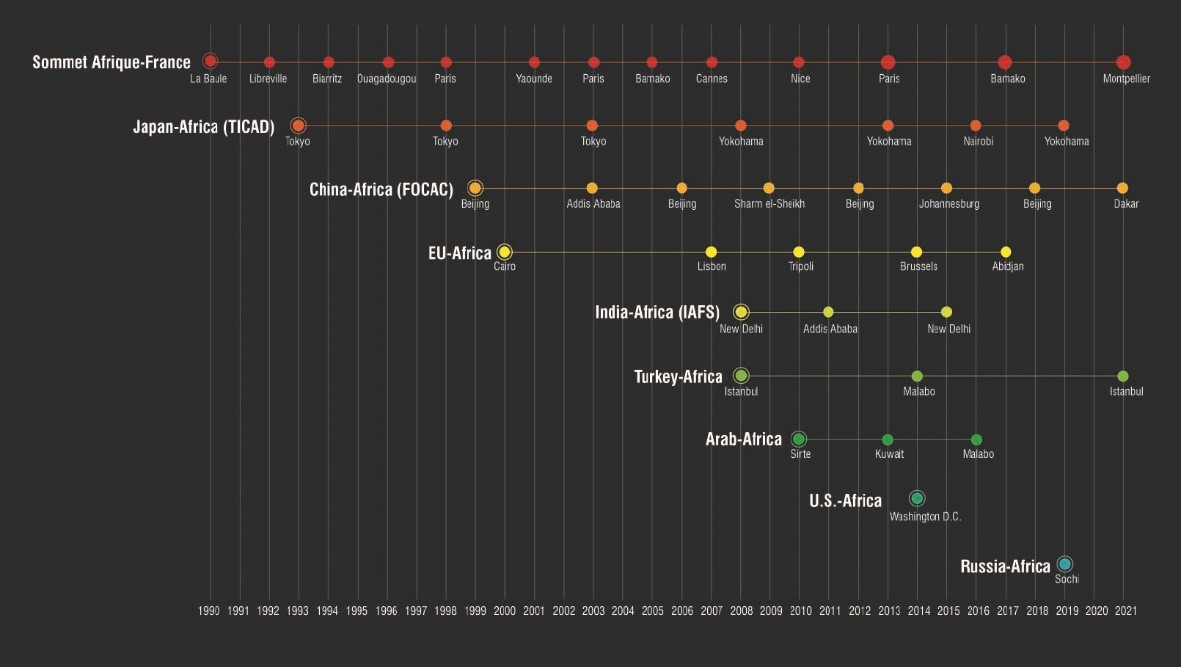

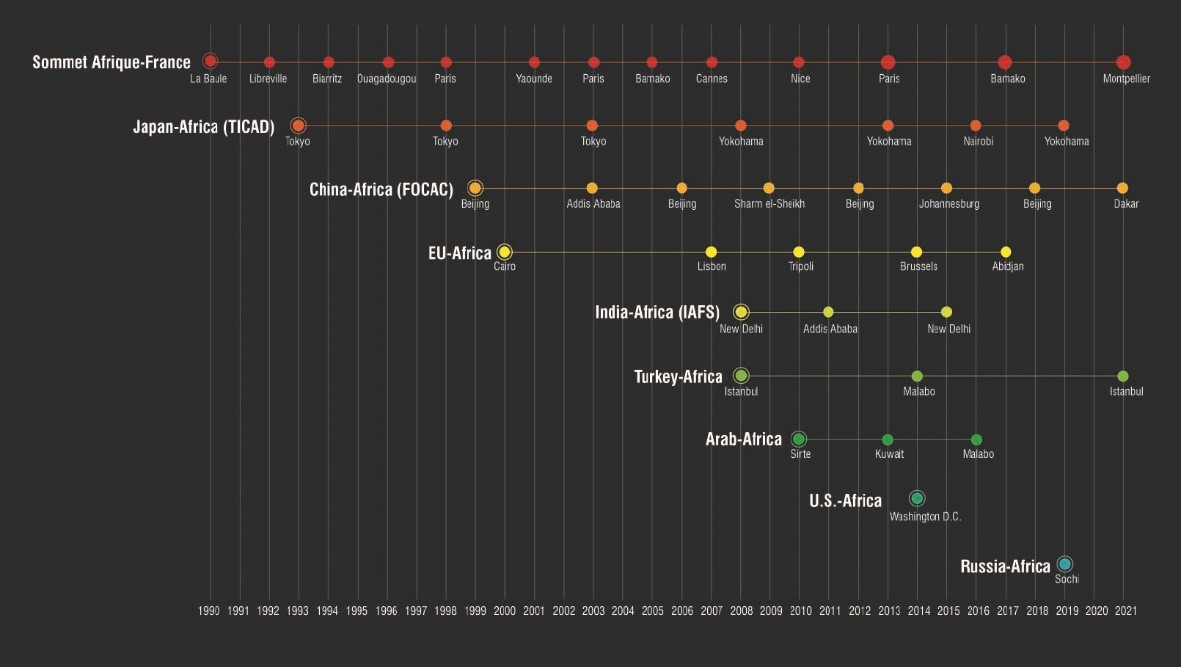

Figure 1. Regional Summits with African Heads of Government (1990-2021)

Source: Author’s own, using data from Folashade Soule and CSIS report, 2021.[12]

A number of other countries have also engaged with Africa in various plurilateral forums.

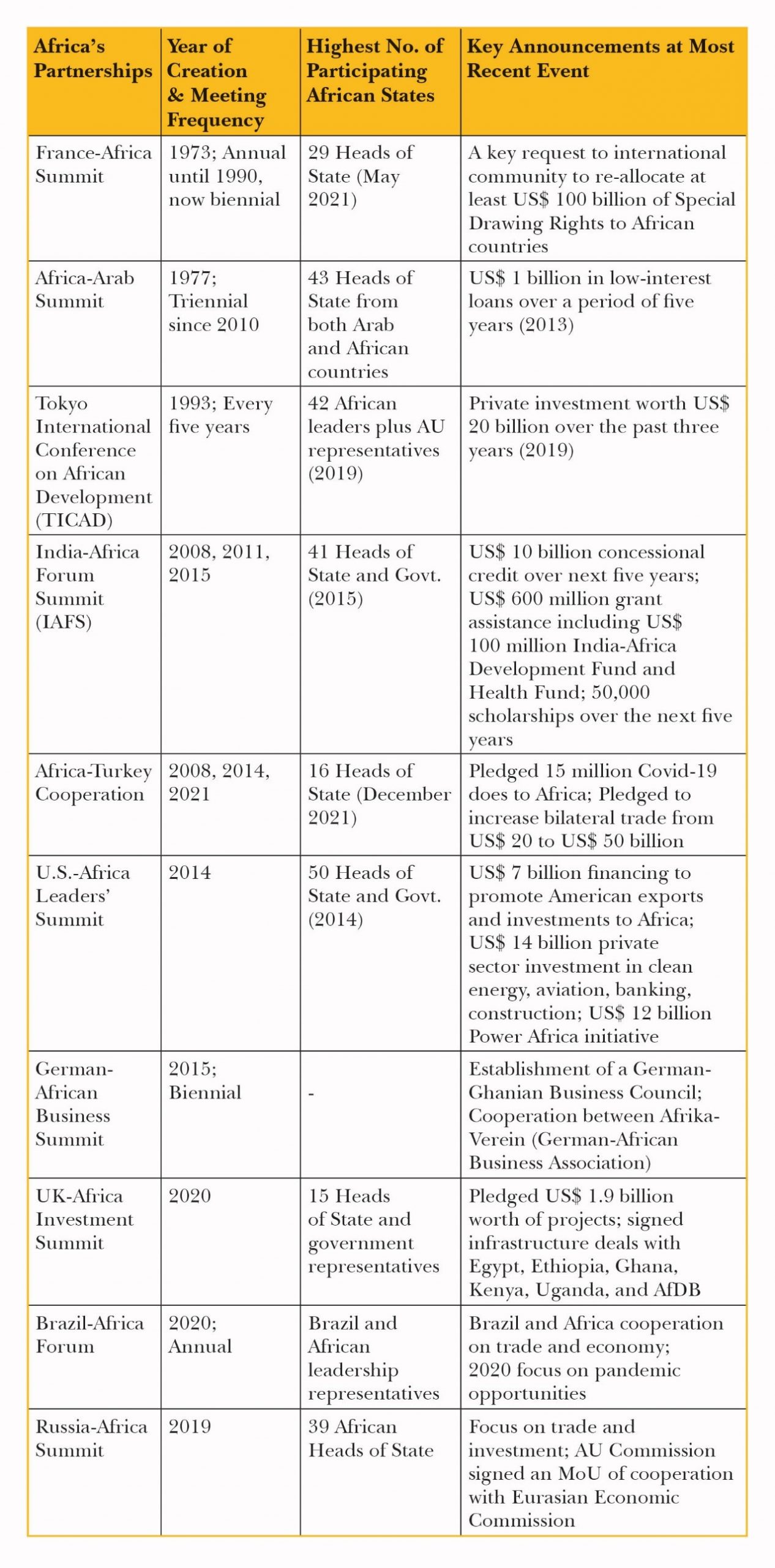

Table 1. Africa’s Plurilateral Platforms

Source: Development Reimagined (December 2021)[13]

An increasing number of African heads of state and government have attended these meetings, generating mutual trust and international awareness regarding Africa’s developmental needs. Most of these summit meetings have led to more open, accountable, diverse and multifaceted engagement. All this underlines the growing use and utility of multilateral forum summits as a tool of diplomacy.

Summit Diplomacy with Chinese Characteristics

China’s summit diplomacy is underpinned by the Five Principles of Peaceful Co-existence (known as Panchsheel).[a] Its aim is to safeguard its sovereignty, security, and development, while developing friendly and cooperative relations with other developing countries. It seeks to showcase China’s evolving “role in global governance as an active participant and contributor in existing international institutions and an advocate of international cooperation, common development, multilateral trading system, and promoter of global governance.”[14] It is useful to acknowledge that both international and domestic factors have informed China’s engagement with countries through summit meetings.

Since the end of the Cold War, the global political and economic environment has witnessed various shifts and changes. The globalisation process once led by the West is facing a crisis of leadership and simultaneously, emerging and non-Western countries are rising in profile. Since the 1990s, developing countries like China, India, and Brazil, among others, have succeeded in narrowing the gap between their economic strength and that of the Western countries. Due to growing interdependence among countries, the common interests between China and other countries have multiplied. As Honghua Men, Professor of Tongji University and Xiao Wang argued in 2018, “The needs of new value in international cooperation and new agenda of mutual benefit and win-win results are the external conditions for China to carry out summit diplomacy actively.”[15]

On the domestic front, China’s rapid rise and transformation has been an important driver in its engagement with summitry. Since the 1990s, China’s GDP has grown steadily and in 2021, stood at US$17.73 trillion, according to data from the World Bank.[16] China has the largest foreign exchange reserves in the world, and a few years ago, in 2014, it surpassed the United States to become the world’s biggest economy in purchasing-power-parity terms.[17] According to a report by McKinsey Global Institute, China in 2018 accounted for 16 percent of world GDP.[18]

The 18th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CPC) at the end of 2012 marked a pivotal movement in China’s engagement in summits. It was the time when the Chinese economy recorded astonishing growth and marked a new historical departure, particularly since it began on its economic reforms. The so-called “socialism with Chinese characteristics” entered into a new stage of development. This phase was marked by attempts by the Chinese government to rebalance its economy in an effort to achieve a “new normal” of slower but sustainable economic development.[19] At the same time, the global economic governance architecture faced a leadership crisis. The values and concepts of global governance continued to diversify while new market economies were emerging. This gave Beijing not only the opportunity to set the agenda for global economic governance at existing global summits like the G20 Summit, but also to play a leading role in setting the new agenda in inter-regional summits.[20] The most visible and prominent demonstration of this role lies in China-Africa cooperation.

China and Africa’s partnership has grown continuously over the years, and now covers domains such as foreign direct investment (FDI), bilateral trade, security, and personnel and diplomatic exchanges. Indeed, Beijing has worked to elevate its ‘comprehensive strategic partnership’ with African countries from one-way aid to a mutually beneficial relationship. Combined with the Belt and Road Initiative’s (BRI) emphasis on infrastructural development of railways, aviation, and port connectivity—which remains an acute and immediate demand for most African countries—China has cemented its place as an attractive and alternative developmental partner on the African continent.[21] Perhaps representing one of China’s biggest diplomatic successes in recent years is the institutionalisation of China and Africa’s partnership under the framework of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC).

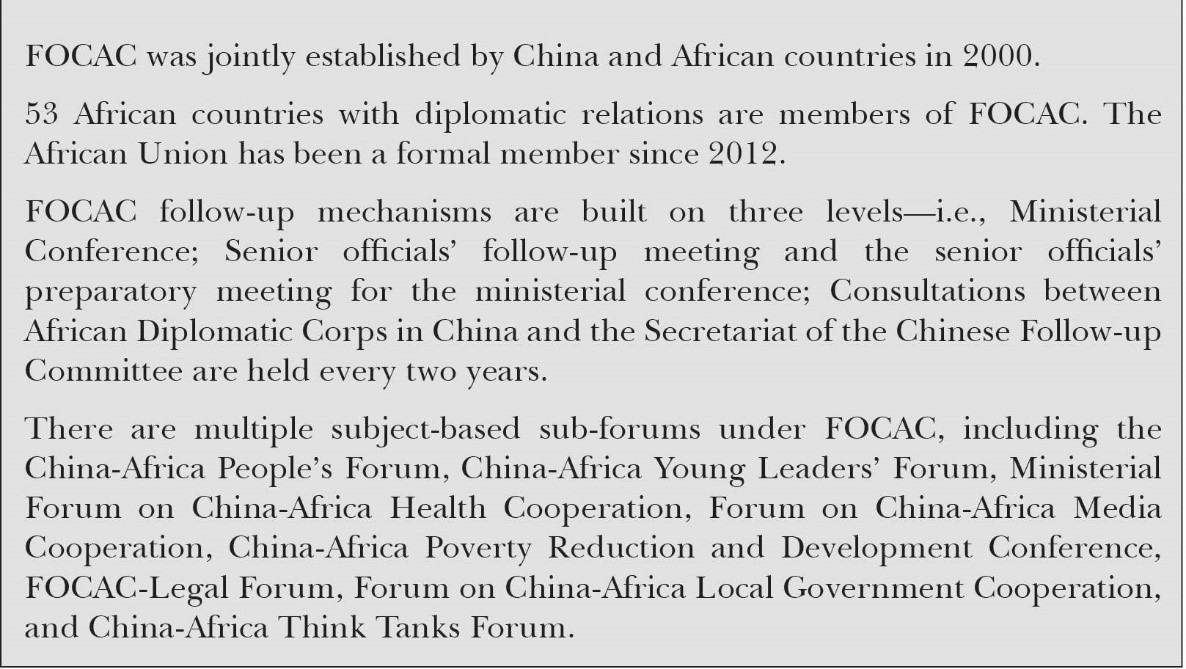

What is FOCAC

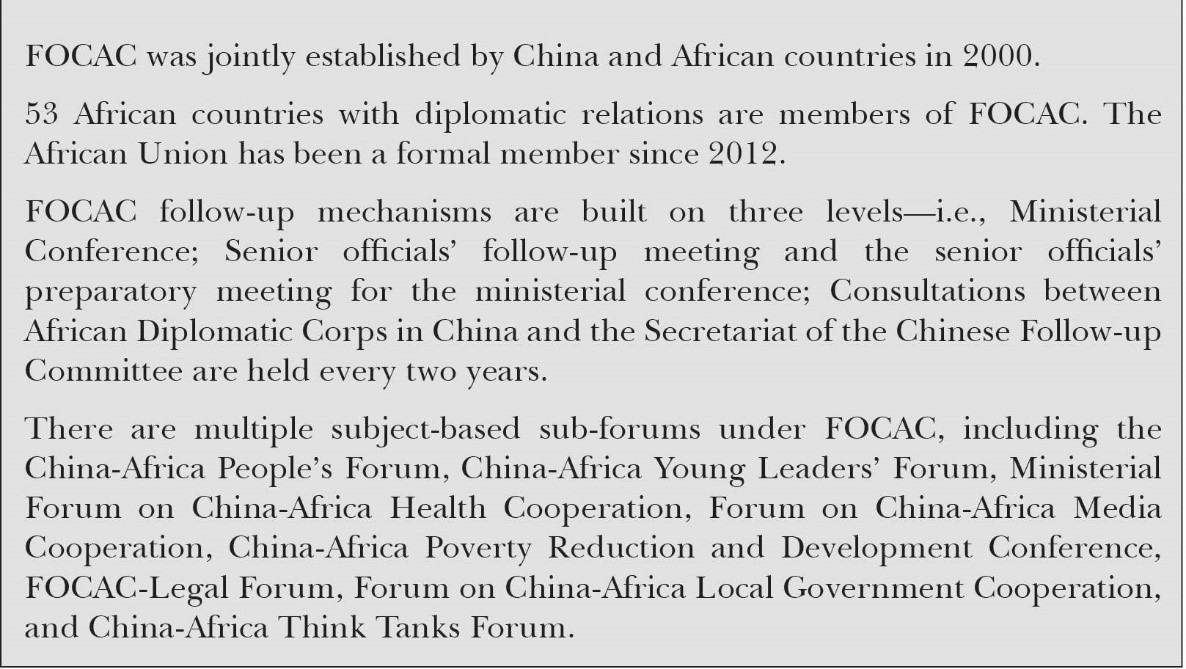

FOCAC was established in 2000 as a platform to promote diplomatic, trade, security, and investment relations between China and 53 African countries.[b] It was one of the first regional organisations established by China outside of its territory. The initial call to set up such a mechanism was proposed by the then Foreign Minister of Madagascar Lila Ratsifandrihamanana.[22]

Box 1. A Snapshot of FOCAC

Source: Development Reimagined (June 2021)

At the time of FOCAC’s inception, African states were already engaging with a wide array of international partners such as the United States (via the U.S.-Africa Business Forum), the European Union (EU-Africa Summit), and Japan (Tokyo International Conference on Africa Development TICAD), among others. Subsequently, it became incumbent upon Beijing to carve a niche for itself and offer a unique package of economic, political, and security inducements to fast-track its entry and access newer markets in the resource-rich African continent. According to political economist Shirley Zi Yu, FOCAC has evolved “from a forum of diplomatic exchange and development-centric body to a comprehensive economic-political-security soft power nexus, which advances China’s long-term vision in Africa.”[23]

The FOCAC process has offered Africa a new opportunity to forge a mutually-beneficial partnership with China, advance the ideals of South-South cooperation, and reduce the continent’s traditional dependence on the US and former colonial Western donors.

Evolution of the FOCAC process

Up until the year 2000 when the first ministerial conference of FOCAC was held in Beijing under then President Jiang Zemin, China was a marginal player on the world stage, with little economic heft on the African continent. When FOCAC was established, therefore, the initial focus was on increasing trade relations between China and Africa. This was also the time when China was on the verge of becoming a member of the World Trade Organization (WTO). China would become the world’s largest exporter within the next decade. The first FOCAC summit in 2000 saw China exempting 10 billion RMB-yuan worth of loans owed by heavily indebted poor countries and least developed countries (LDC) in Africa. Beijing also set up an Africa Human Resource Development Fund in an effort to help African countries train professional talent in various domains.

In 2003 at the second FOCAC summit, China granted tariff-free market access to some products from LDCs in Africa, adopted the FOCAC Addis Ababa Action Plan (2004-2006), and offered to train thousands of African personnel in various fields over the next few years. By the time the 2006 FOCAC summit was held in Beijing, over 440 items from African LDCs could be exported to China.[24] Beijing also offered US$ 3 billion in preferential loans and US$ 2 billion in preferential buyer’s credit to various African countries. This period witnessed two-way trade between Africa and China grow 5.2 times.[25]

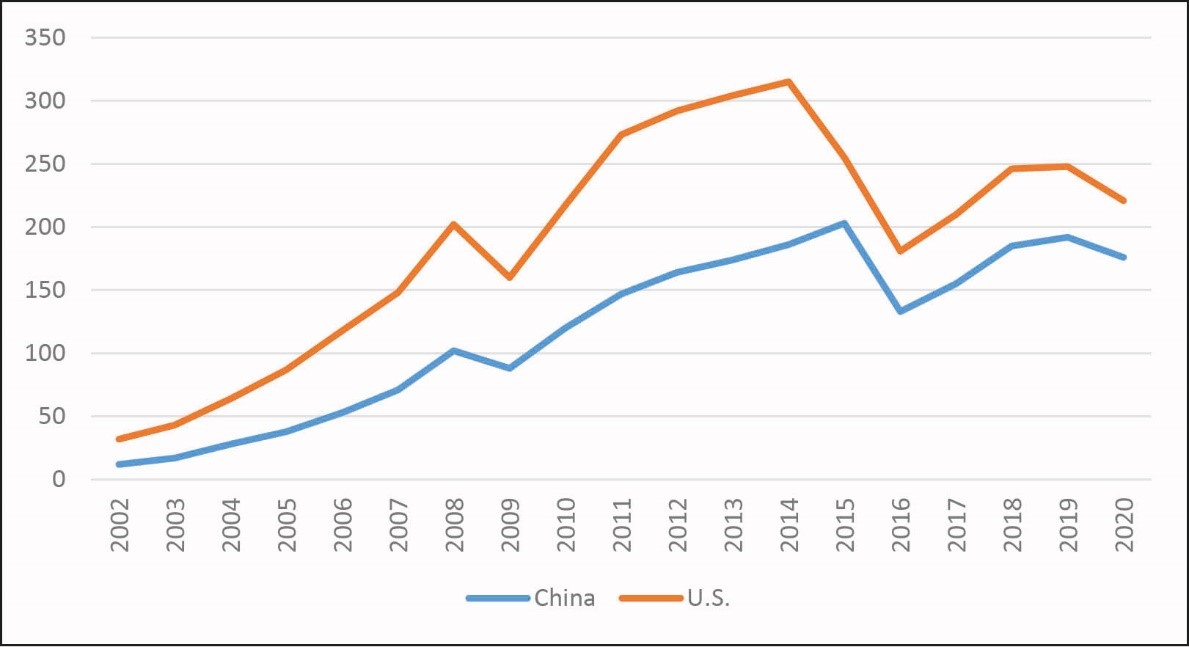

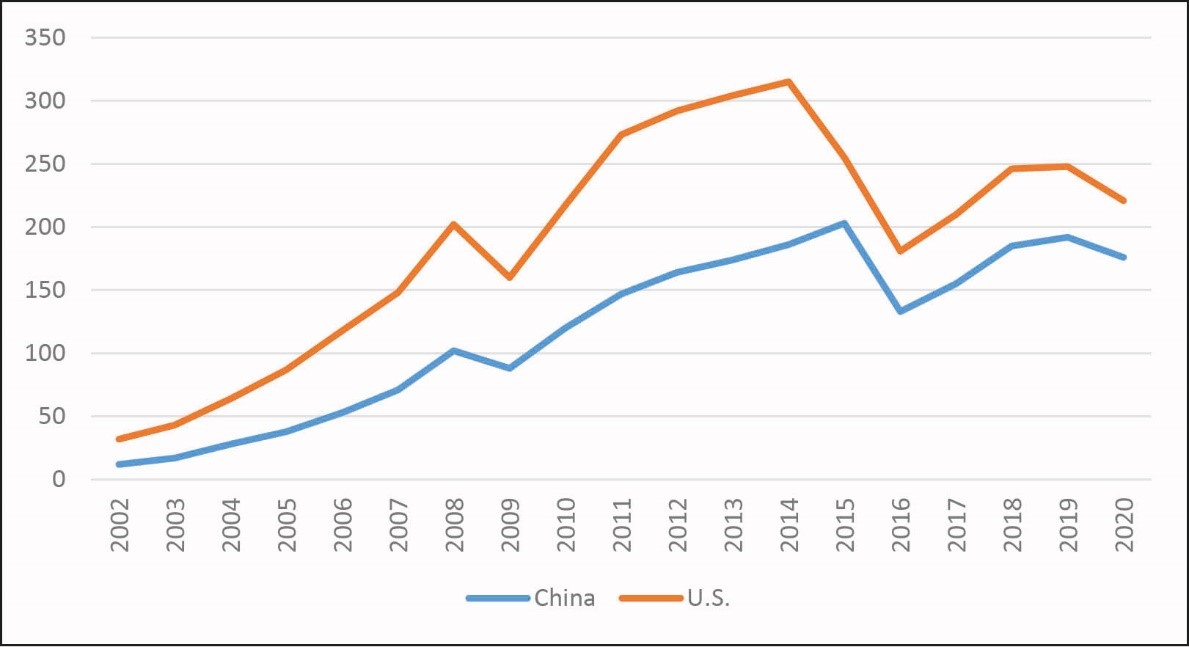

From 2006 onwards, China expanded the focus of the partnership from trade to encompass direct investment, foreign aid, and development finance. Then Chinese President Hu Jintao pledged to double China’s financial aid during this period and offered US$ 5 billion in preferential loans and credit to Africa, which subsequently reinforced China’s ballooning presence as a creditor in the continent. Chinese companies focused on developing special economic zones, free trade zones, and industrial parks across the continent. This became a necessity in order to create efficient supply chains and upgrade production capacity. By 2009, China had surpassed the United States to become Africa’s largest trade partner.[26]

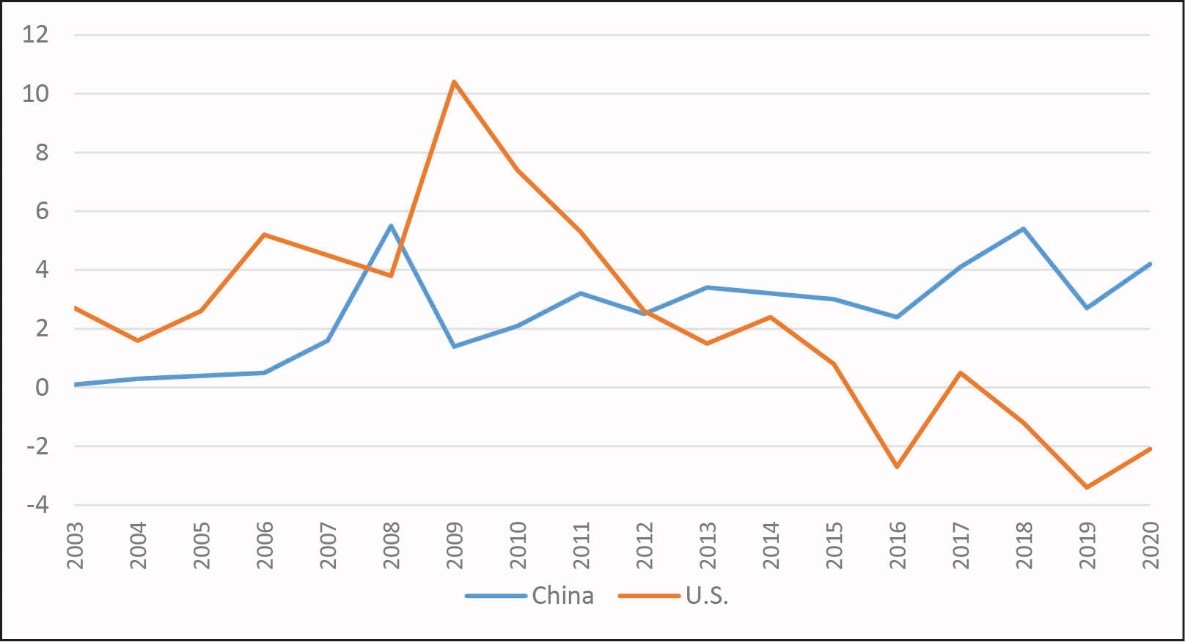

Figure 2. Chinese and US Trade with Africa (2002-2020, in US$ billions)

Source: Author’s own, using SAIS CARI data[27]

In 2013, China launched its flagship Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) that aims to build connectivity and cooperation and facilitate greater infrastructure, trade, financial, and people-to-people connectivity between China and developing countries. Various reasons explain why African leaders find the BRI to be an attractive, alternative model for development. The foremost reason is that the BRI’s emphasis on trans-continental infrastructural development of railways, highways, aviation, and port-connectivity dovetails with Africa’s top priorities as outlined in its Agenda 2063.[28] By investing billions of dollars across an array of projects under the BRI, China is seeking to bolster its reputation as Africa’s leading partner in building infrastructure, and setting up ports, special economic zones, power grids, and transportation routes in the continent. Through the BRI, China has been able to source loans for projects in African countries that are often not financed by other bilateral partners nor by multilateral development banks. Compared to other Africa’s development partners like the US or EU, China has been willing to fund these projects through multiple financing models.[29]

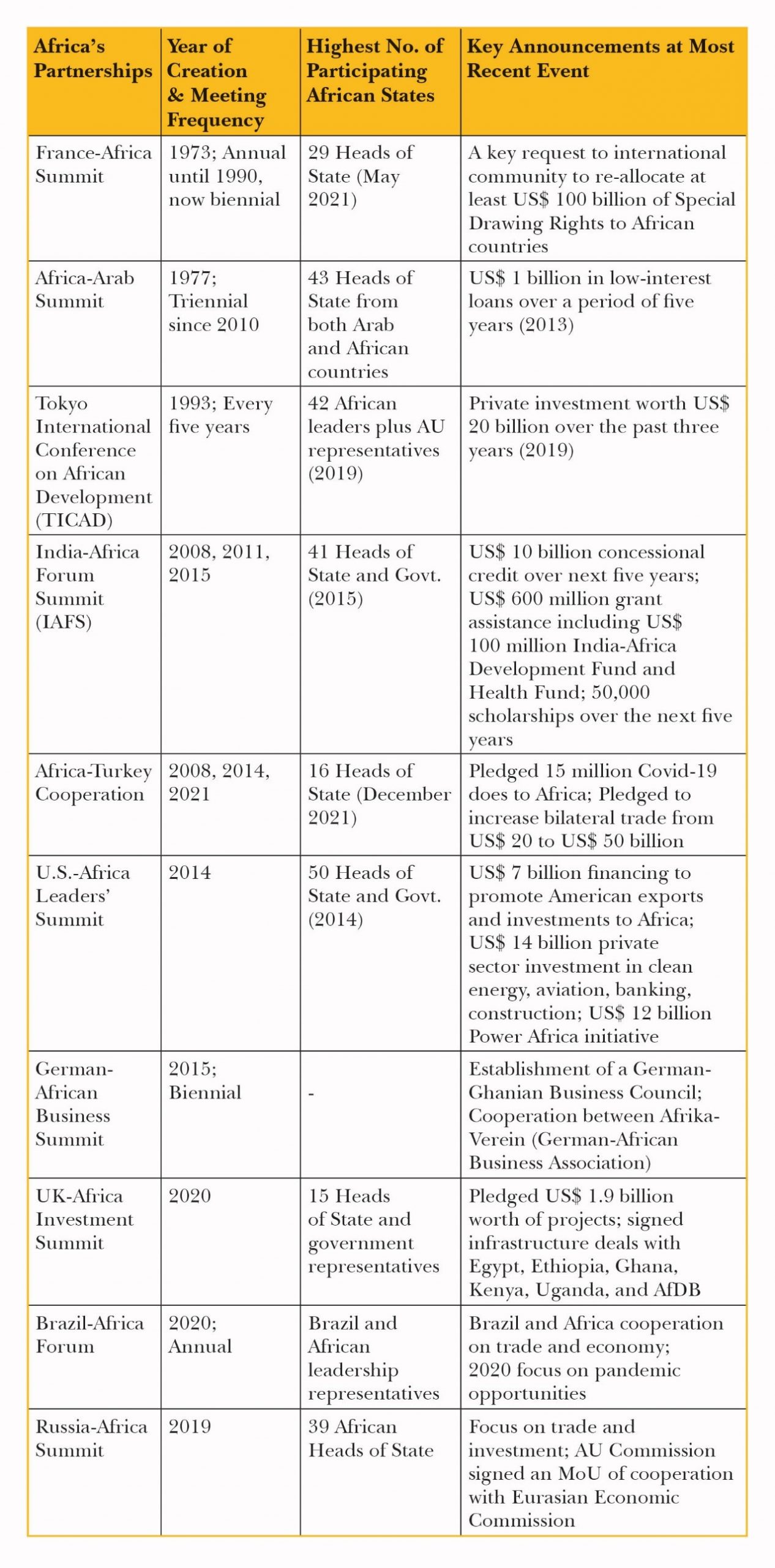

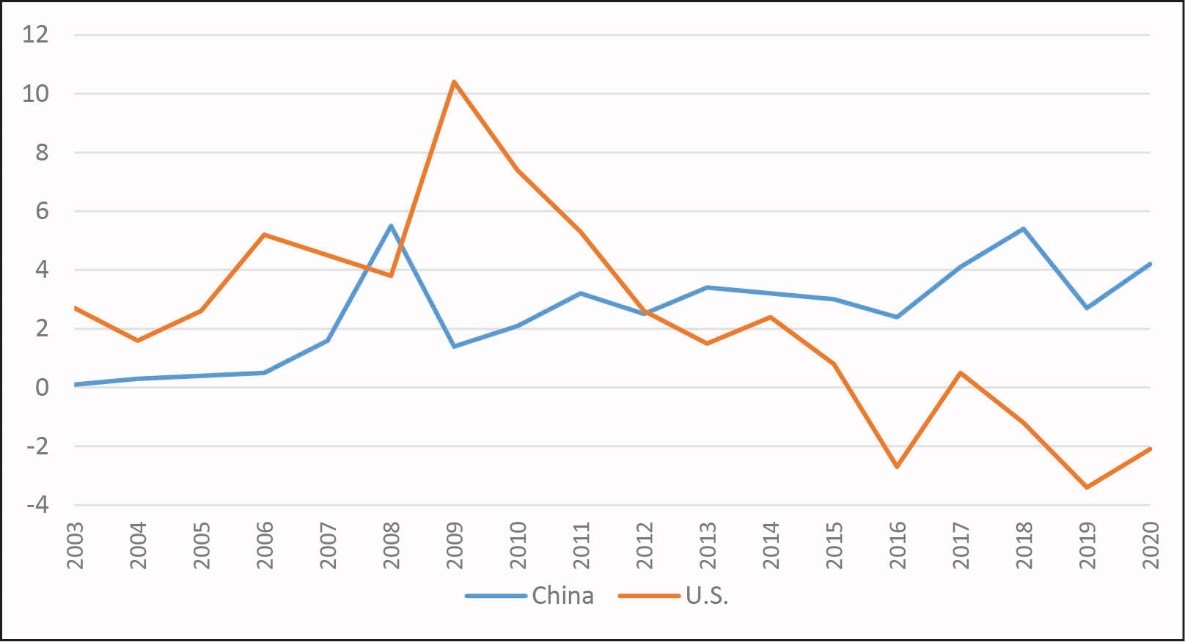

Figure 3. Chinese FDI Vs. US FDI to Africa (2003-2020, in US$ billions)

Source: Author’s own, using SAIS CARI data[30]

FOCAC’s 2015 summit in Johannesburg and 2018 summit in Beijing were both milestones. China consolidated security and political partnerships with African countries as core pillars of FOCAC and envisioned a ‘China-Africa Community of Common Destiny’.[31] This reflected China’s desire to maintain regional peace and security to enable economic cooperation and trade with Africa. As Lei Yu, Charhar Institute Fellow opines, Beijing desires to provide itself with safe access to African markets, resources, and investment destinations “in order to sustain its economic growth that bases its long-cherished dream of restoring its past glory of ‘Fuqiang’ (wealth and power) and rise in the global power hierarchy.”[32]

During both these summits, high-level, continent-wide pledges from China to Africa increased. An example is China’s financial commitments (in both loans and grants) which increased from US$ 35 billion in 2015 to US$ 45 billion in 2018.[33] The number of African personnel that China committed to training in various fields also increased from 30,000 in 2012, to 40,000 in 2017, and to 50,000 in 2018. The US$ 5-billion China-Africa Development Fund announced at the 2006 FOCAC summit has since been increased to US$ 10 billion. This has supported Chinese investments in Africa, including six Special Economic Zones in five African countries: Nigeria, Ethiopia, Zambia, Egypt, and Mauritius. In 2018, another US$ 5-billion special fund for financing imports from Africa to China was pledged.[34]

Even though China has historically displayed a pattern of doubling or tripling previous FOCAC’s pledges, the situation was different during the 2018 summit. China began to pursue a more cautious approach and rebranded its engagement in Africa. This is mostly due to accusations of Beijing engineering “debt traps” for developing countries by offering cheap loans that would be impossible to repay. In turn, China is expected to take control of a country’s strategic asset in the event of a failure to repay the loan. In Africa, in particular, China has been accused of both “debt trap” diplomacy and, more generally, of “neo-colonialism”— a charge which Beijing has repeatedly denied.[c],[35] Subsequently, as Yun Sun, Director of the China Program at the Stimson Center noted in 2018, “the overall level of concessionality and preferentiality of Chinese financing began to decrease.”[36]

This trend is likely to continue in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic which has triggered a trend towards slow growth and de-globalisation. China has been concerned about the returns and commercial viability of the Chinese financing. Towards this end, Beijing has been signalling its desire to shift towards a private-sector-to-private-sector financing model. China is no longer providing hard cash to debt-ridden African countries as they attempt to navigate the economic disputations caused by the pandemic.[37] The period of sustained Chinese financing for building infrastructure in Africa is declining. Instead, as the former Liberian Minister of Public Works, Gyude Moore notes, as Chinese retrenchment from infrastructure financing continues, resulting in a reduction in the volume of projects, China is likely to undertake more targeted lending under more stringent terms.[38]

Structural Asymmetries in China-Africa Partnership

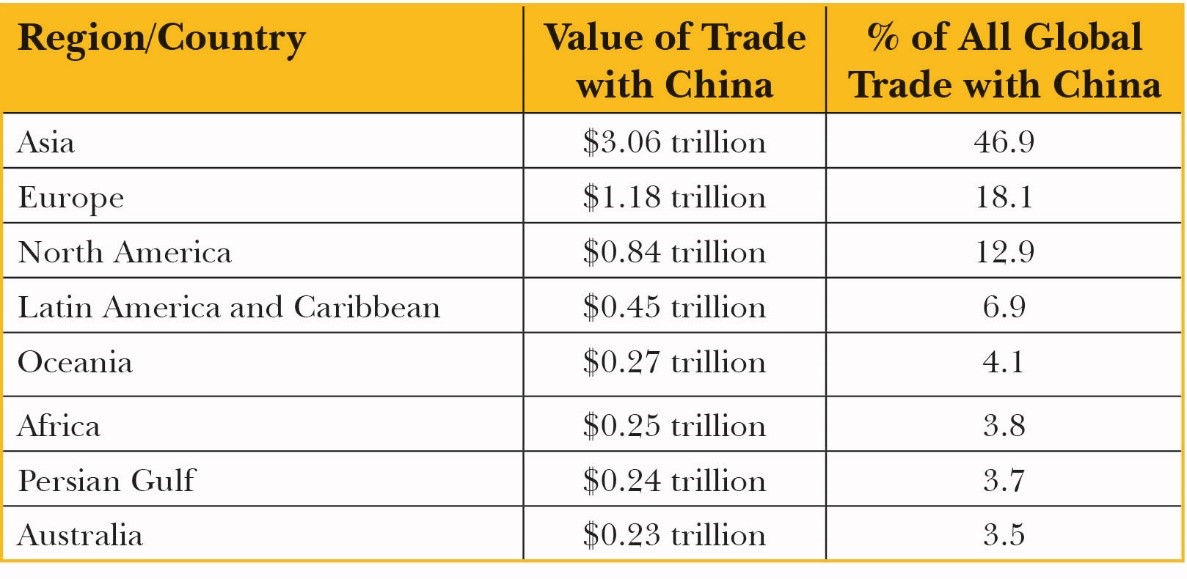

From the above discussion, it is clear how the FOCAC process has evolved and helped China solidify a single, favourable perspective on China-Africa relations in the eyes of African countries. However, China’s economic and commercial relations with African countries continue to remain massively asymmetric. The glaring mismatch in exports and imports, and the resultant acute trade imbalance is a key concern for African countries. China mostly tends to import raw materials from African countries and export manufactured, value-added products to these markets. African countries tend to export oil, agricultural products, ores, and precious metals. Due to this lack of export diversification, many African countries remain extremely vulnerable to external shocks, most recently witnessed in the commodity price slumps from Covid-19 impacts. Overall, the dual factors of trade imbalance and lack of value-addition dampens possible job creation and foreign exchange generation. Despite a year-on-year growth in China-Africa bilateral trade, the continent is one of Beijing’s smallest trade partners, with trade between the two making up around 4 percent of China’s overall trade.

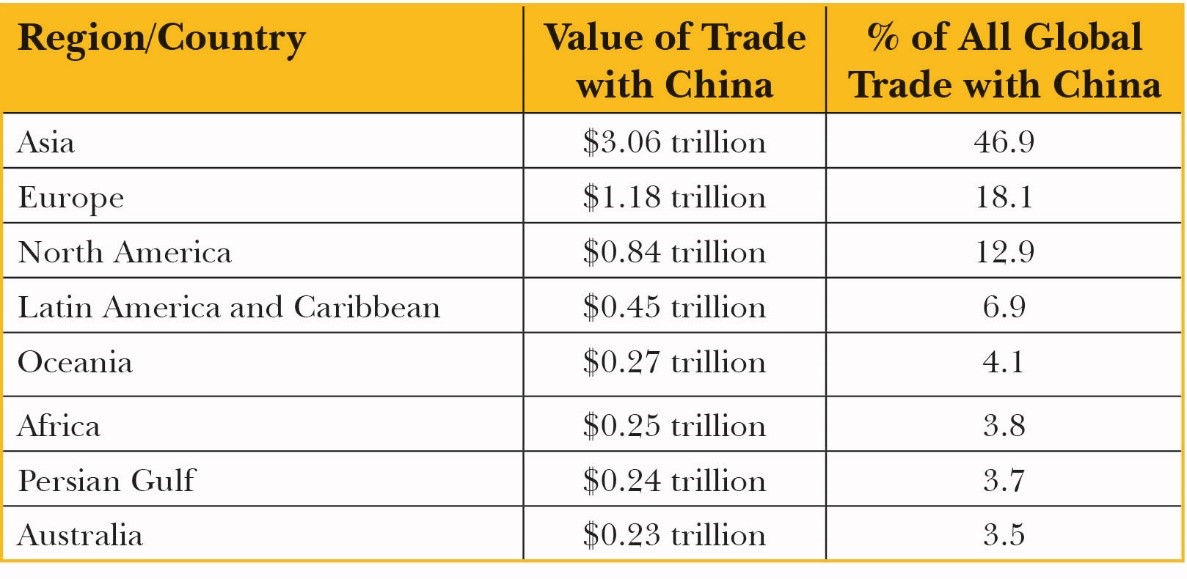

Table 2. Value of Trade with China (2021, in US$ trillions)

Source: Quartz Africa, February 2022[39]

To be sure, African countries have gained benefits from their engagement with China. However, this engagement has not helped African countries achieve industrialisation and structural transformation, particularly due to the asymmetrical and uneven nature of the relationship. For one, the catalytic effect of Beijing’s economic engagement with Africa has been uneven across countries. In most instances, the countries that have benefitted are those that demonstrate a proactive and strategic approach in their negotiations with China and adopt policy ownership.[40]

For example, when it comes to trade facilitation between Africa and China, African countries should look to strategically adopt policies aimed at modernising its transport and logistics industry, and improving regional connectivity. They could also look at reforming their banking and customs system with a focus on enhancing harmonisation and automation. The African products that are to be exported to Chinese markets should undergo surveillance and focus on value addition. Meanwhile, in infrastructure connectivity, African countries should look to develop infrastructure development strategy and master plans that prioritise utilities critical for manufacturing and export like energy, industrial infrastructure, and transport. In addition, know-how transfer, skills formation, developing links with local firms, using alternative financing schemes, and debt and environmental sustainability should be given due consideration. Many of these issues were key concerns for African states in the run-up to the 2021 FOCAC.

FOCAC 2021 and China’s shifting priorities

Beijing’s shifting priorities and move away from infrastructure-centric and loan-heavy approach was evident in the latest edition of the FOCAC ministerial meeting concluded in December 2021 in Dakar, Senegal. A number of documents were adopted during the summit, although there is considerable overlap in terms of coverage and substance in these documents.[d] The biggest change was the quantitative reduction in China’s financial commitments of US$ 60 billion in FOCAC 2018 to US$ 40 billion in FOCAC 2021.[41] Planned activities in Africa in various categories are also being scaled back, such as those in agricultural assistance, health, scholarships, peace and security, climate, and environment.[42]

The omission of infrastructure from China’s latest commitments at the FOCAC 2021 summit is indeed glaring. Controversies like the potential seizure of Kenya’s Mombasa Port, recurring debt repayment issues of Zambia, and the alleged takeover of Uganda’s Entebbe International Airport by China, loomed large in the background of the last FOCAC meeting. These instances might have played a part in China’s scaling back of activities in the continent. However, the lack of reference to infrastructure development and financing in FOCAC’s commitment does not suggest that China will exit the domain completely. Already, the large number of ongoing infrastructure projects with loan terms means that China is likely to continue to fund and construct infrastructure projects in African countries for the near future.

Apart from the downplaying of infrastructure development, a striking feature of 2021 FOCAC was the emphasis placed by China on trade promotion and facilitation, especially regarding the increase of African export of agricultural products and non-natural resources. Beijing is aware that the current composition of China-Africa trade is heavily imbalanced in its favour—something that is lamented by African leaders. Both sides are looking to reduce this trade deficit. Subsequently, China announced the establishment of a ‘green channel’ for the export of African agricultural products to China and the expansion of more products under zero-tariff. President Xi Jinping promised to import a total of US$ 300 billion worth of products from Africa over the next three years.[43] While these are impressive numbers, it is hard to imagine that trade could fill the large space that infrastructure development has occupied in China-Africa relations in a meaningful way.[44]

The FOCAC process has been a fundamental instrument in elevating the China-Africa partnership. It has come a long way from its initial focus on defining a new form of a Global South partnership to the forum’s strategic expansion beyond trade engagement underlying an all-encompassing partnership. However, the broader narrative surrounding the FOCAC process and its agenda has been primarily set and driven by China. Africa has been perceived as a region that requires financial aid and assistance from external partners and has been dubbed as ‘rule-takers’ rather than ‘rule-makers’. Till date, no African country has published a ‘China Strategy’ or for that matter a ‘India Strategy’ or ‘Europe Strategy’. This is problematic as it may lead to disjointed policies that may not necessarily align with the national development priorities of African countries. That being said, high-level meetings dubbed as ‘Africa+1 summitry’ have become popular in recent years, which indicates that the African continent is today a subject of rising interest.

Exploring African agency within summit processes

The engagement of global powers with African countries in the form of summits is often analysed through the lens of geopolitical rivalry between traditional and emerging partners. However, this narrative fails to sufficiently understand the motives and strategies adapted by African leaders who participate in these summit meetings. Treating the continent solely as a commodity subject to geopolitical competition ignores the fact that African governments and leaders are strategically and wisely choosing their partners.[45]

It is important to understand that African leaders chose to attend some summits and not others. The level of representation, in terms of how many heads of state and government attend summits, is a sign of a country’s interest in a particular event. In the wide array of summits that African leaders today participate in, they are not passive bystanders or recipients, but are leaders that are actively part of agenda-setting.

According to Folashadé Soulé of the University of Oxford, there are four motives that explain why African countries are engaging in summit diplomacy.[46] The first reason is to attract foreign investments from a diverse set of partners in a competitive environment. African countries are competing with each other to position themselves as regional economic hubs. This is a common priority among most African countries and is sometimes an election issue for politicians and political parties in order to appease domestic vote banks. Towards this end, the Africa+1 summits are useful platforms for African countries to showcase their respective capacities to provide a safe environment for investment opportunities. The second motive for African leaders and countries to participate in these summit meetings is to diversity its partners and reduce dependence on one or two. An example of this is the heavy reliance that African countries have on China for infrastructure funding. Having a diverse set of partners accords African countries an opportunity to leverage competition between traditional and non-traditional partners and derive the most benefits for themselves.

A third reason why summits are appealing is because they provide a platform to African leaders to voice their concerns on issues like debt and the manner in which loans are disbursed to African countries. There are several diverging views on the level of debt that African countries are accumulating. On one hand, certain institutions like the IMF and World Bank are ringing the alarm bells on the risk of a debt burden. On the other hand, several African governments argue that the continent is not borrowing too much.

This line of argument became evident in 2019 when six West African heads of state aired their grievances about rules imposed by multilateral institutions, especially the IMF, regarding budget deficits and public debt.[47] They argued that orthodox financial rules limit the inflow of FDI into the continent. This joint economic policy eventually came to be known as the ‘Dakar consensus’ as opposed to the ‘Washington consensus’. Finally, forum summits offer a platform for unpopular, authoritarian leaders to attend and raise their individual profile at a global stage. Attending these summits offer these leaders a chance to be heard in a foreign capital.

Conclusion

Summitry has emerged as an important instrument to help achieve and enhance convergences, cooperation and collaboration between China and African countries. Since its institutionalisation in 2000, the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) partnership platform has undergone multiple stages of evolution. The overarching nature of summit declarations has ensured that many more focus-areas/sectors are added to the cooperative frame that FOCAC process has involved and enriched.

The mechanism has boosted the bilateral ties that African countries have with China. Beijing has been responsive to African demands and is attempting to develop a holistic partnership that are aligned with their national development plans as enshrined in Africa’s Agenda 2063, as well as the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Overall, the summitry mechanism both as a diplomatic tool and a cooperation framework has proved its relevance and value, and is expected to remain useful to both China and African countries.

Endnotes

[a] The Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence, commonly known as Panchsheel, were first mentioned in the Sino-Indian Agreement, 1954. They are a set of principles whose purpose is to govern relations between states and reflect the aspirations of all nations to co-exist and prosper together in peace and harmony. The five principles are; Mutual respect for each other’s territorial integrity and sovereignty; Mutual non-aggression; Mutual non-interference; Equality and mutual benefit; and Peaceful co-existence

[b] The exception is Eswatini, which maintains diplomatic relations with Taiwan.

[c] China has been known to forgive interest-free loans for African countries in order to dispel accusations of practicing “debt trap” diplomacy. However, interest-free loans as opposed to interest-bearing loans make up for a very small portion of Beijing’s overall lending to Africa. The problem is that commercial loans can often be reprofiled or restructured, but are rarely considered for cancellation. An analysis of Chinese lending patterns highlights the prevalence of Non-Disclosure Agreement (NDA) clauses which forbids the borrowing country from disclosing details of the agreements. Additionally, in the event of a need to seek resolution of any disputes, Chinese contracts tend to bind the borrowing country to seek resolution at the China International Economic and Trade Arbitration Committee in Beijing. This eventually limits the borrowing country’s crisis management options and gives Chinese lenders an advantage and leverage over borrowing country. For more, see https://www.theeastafrican.co.ke/tea/business/kenya-makes-public-sgr-contract-which-gives-china-sweeping-powers-4011354

[d] The documents that were adopted at the 8th ministerial conference on FOCAC were: The Dakar Action Plan (2022-2024); the 2035 Vision for China-Africa Cooperation; the Sino-African Declaration on Climate Change; and the Declaration of the Eight Ministerial Conference of FOCAC

[1] Inis L. Claude, Swords Into Ploughshares: The Problems and Progress of International Organization, (Random House USA Inc: 1988) pp. 52.

[2] Jan Melissen, “Summit Diplomacy Coming of Age,” Issue (86). pp. 1-21. Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingeldael’, Desk top publishing: Birgit Leiteritz: 2003).

[3] G.R. Berridge, Diplomacy: Theory and Practice, (Palgrave Publisher, 2nd Edition: 2002).

[4] Jorge Heine, “On the Manner of Practicing the New Diplomacy (Working Paper No. 11),” The Center for International Governance Innovation, (2006), Canada: Palgrave Macmillan UK

[5] David H. Dunn, Diplomacy at the Highest Level: The Evolution of International Summitry (London: Palgrave Macmillan UK Publisher, 1996).

[6] David, H. Johns, “Diplomatic exchange and inter-state inequality in Africa: an empirical analysis” in Timothy, M. Shaw. &. Kenneth, A. Heard (Eds.) The Politics of Africa: dependence and development (London: Longman, 1979) pp. 269-84.

[7] Richard Hodder Williams, An Introduction to the Politics of Tropical Africa. London: Allen and Unwin Publisher, 1984) pp. 69-76.

[8] Colin Legum, Panafricanism: a short political guide, (New York: Praeger, 1961)

[9] Catherine Hoskyns, The Organisation of African Unity and the Congo Crisis 1965-65: case studies in African diplomacy: 1. (Oxford University Press for the Institute of Public Administration. Dar es Salaam: 1969)

[10] M, Tamarkin, The Making of Zimbabwe: decolonization in regional and international politics (London: Frank Cass, 1990) pp. 250-51.

[11] On the importance of summits to political leaders, see Williams, African Summitry in Dunn, Diplomacy at the Highest Level: The Evolution of International Summitry.

[12] Folashadé Soulé, “How Popular are Africa+1 Summits Among the Continent’s Leaders?” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, December 6, 2021.

[13] Patrick Anam and Hannah Wanjie Ryder, “Reimagining FOCAC going forward: An African Assessment of Needs, Demands and Opportunities for FOCAC 2021 and Beyond”, Development Reimagined, 2021.

[14] Honghua Men and Xiao Wang. “China’s Summit Diplomacy (1993-2008): Progress, Evaluation and Prospects”, p.172., in Honghua Men (ed.), Report of Strategic Studies in China (2018): Domestic Development, Sino-American Relations and China’s Grand Strategy, Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd, 185 pp.

[15] Men and Wang, China’s Summit Diplomacy (1993-2008): Progress, Evaluation and Prospects

[16] The World Bank, “GDP (current US$) – China”, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?locations=CN

[17] “China set to overtake U.S. as biggest economy in PPP measure”, Bloomberg, May 1, 2019.

[18] Jonathan Woetzel, et.al. China and the world: Inside the dynamics of a changing relationship. McKinsey Global Institute, July 2019.

[19] Jing Zhang and Jian Chen, “Introduction to China’s new normal economy,” Journal of Chinese Economic and Business Studies, 15, Issue 1, (2017), https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14765284.2017.1289454.

[20] Men and Wang, China’s Summit Diplomacy (1993-2008): Progress, Evaluation and Prospects

[21] Abhishek Mishra, “Counting the Risks and Rewards of the BRI” in Harsh V. Pant and Premesha Saha (Ed). Mapping the Belt and Road Initiative: Reach, Implications, Consequences. February 2021, Observer Research Foundation.

[22] Li Anshan, Liu Haifang, Pan Huaqiong and Zeng Aiping, “FOCAC Twelve Years Later: Achievements, Challenges and Way Forward,” Nordiska Afrikainstitutet (Uppsala: Sweden, 2012)

[23] Shirley Ze Yu, “What is FOCAC? Three historic stages in the China-Africa relationship,” London School of Economics and Political Science Blogs, (February 3, 2022)

[24] “Chronicle of FOCAC,” Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in the Republic of Liberia.

[25] Shirley Ze Yu, What is FOCAC? Three historic stages in the China-Africa relationship

[26] Kingsley Ighobor, “China in the heart of Africa,” Africa Renewal, (January 2013)

[27] “Data: China-Africa Trade,” China-Africa Research Initiative, Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies, http://www.sais-cari.org/data-china-africa-trade

[28] Nancy Githaiga, Alfred Burimaso, Wang Bing, and Salum Ahmed, “The Belt and Road Initiative: Opportunities and Risks for Africa’s Connectivity,” China Quarterly of International Strategic Studies, 5, no. 1 (2019): 124.

[29] Development Reimagined, “Flagship Report: Options for Reimagining Africa’s Debt System” (February 2021)

[30] China-Africa Research Initiative, Data: Chinese Investment in Africa

[31] Denghua Zhang, “The Concept of ‘Community of Common Destiny’ in China’s Diplomacy: Meaning, Motives and Implications”, Asia & The Pacific Policy Studies, Vol 5, no. 2, (May 2018).

[32] Lei Yu, “China’s Expanding Security Involvement in Africa: A Pillar for ‘China-Africa Community of Common Destiny’” Global Policy, 9, no. 4 (August 2018).

[33] Patrick Anam and Hannah Wanjie Ryder, “Reimagining FOCAC going forward: An African Assessment of Needs, Demands and Opportunities for FOCAC 2021 and Beyond” Development Reimagined (November 2021)

[34] Yun Sun, “China’s 2018 financial commitments to Africa: Adjustment and recalibration,” Brookings, (September 5: 2018)

[35] Deborah Brautigam and Meg Rithmire, “The Chinese ‘Debt Trap’ is a Myth,” The Atlantic, (February 6: 2021)

[36] Yun Sun, China’s 2018 financial commitments to Africa: Adjustment and recalibration

[37] “Big decline in China’s BRI investments, cash grants to Africa: Report,” Business Standard, (December 14: 2021)

[38] Gyude Moore, “Chinese lending decline leaves Africa with huge infrastructure gap,” African Business, (May 26:, 2021)

[39] Carlos Mureithi, “https://qz.com/africa/2123474/china-africa-trade-reached-an-all-time-high-in-2021,” Quartz Africa, (February 8: 2022)

[40] Oqubay, Arkebe, and Justin Yifu Lin, ‘The Future of China–Africa Economic Ties: New Trajectory and Possibilities’, in Arkebe Oqubay, and Justin Yifu Lin (eds), China-Africa and an Economic Transformation (Oxford,2019; online edn, Oxford Academic, 20 June 2019).

[41] David Pilling and Kathrin Hille, “China cuts finance pledge to Africa amid growing debt concerns,” Financial Times, (December 1: 2021)

[42] The Eight Ministerial Conference of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation, “Xi Jinping’s keynote speech at the opening ceremony of the 8th Ministerial Conference of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (full text),” November 29, 2021.

[43] Global Times, “China to import $300 billion products, promote Chinese investment in Africa,” November 29, 2021.

[44] Yun Sun, “FOCAC 2021: China’s retrenchment from Africa?” Brookings,(December 6: 2021)

[45] Folashadé Soulé, “How Popular are Africa+1 Summits Among the Continent’s Leaders?” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (December 6: 2021)

[46][46] Folashadé Soulé, “‘Africa+1’ summit diplomacy and the ‘new scramble’ narrative: Recentring African agency,” African Affairs, 119, no. 477 (October 2020): 633-46.

[47] Alain Faujas, “Forget the Washington Consensus, meet the Dakar Consensus,” The African Report, (December 6: 2019)

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PDF Download

PDF Download

PREV

PREV