Introduction

Seaborne trade has been integral to Asia’s economic growth over the past few decades as it remains the cheapest, and most efficient method of transporting large volumes of cargo over long distances. During times of peace, the sea lines of communication (SLOC) serve as commercial trading routes, but they are also seen as strategic highways that give countries access to resources in faraway places. This is especially relevant to oil and gas shipments, a vast majority of which are transported via the sea.[1] Consequently, SLOC protection has become a crucial condition for the sustenance and growth of regional economies.

Asia’s sea lanes, however, remain vulnerable to a variety of threats. Despite a fall in piracy levels in the Gulf of Aden, geopolitical tensions between world powers continue to imperil regional peace and stability. With the United States and China locked in conflict over Taiwan, and a tense contest brewing between claimant states in the South China Sea, the risks to seaborne trade remain high.[2] Following the visit of US Congress Speaker Nancy Pelosi to Taipei in August 2022, the island province has become a flashpoint in an already strained US-China relationship. Beijing interpreted Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan as a direct challenge to Chinese sovereignty and reacted with characteristic zeal, conducting a series of hostile military manoeuvres in the Taiwan Strait.[3] In response, the Biden Administration moved to deepen support for Taiwan, further aggravating the standoff with Beijing.[4]

The deterioration in US-China ties comes at a time when tensions between Iran and the United States are already rife. Indeed, the US forces in the Western Indian Ocean have been on high alert since Iran seized two American maritime drones in the Red Sea in September 2022.[5] The drone capture by Iran was only the latest in a string of maritime spats between Washington and Tehran. Days earlier, Iran had attempted to seize another US naval drone in the Red Sea—a flagrant violation of maritime law. The provocation from Tehran came days after President Joe Biden attended a regional summit in Jeddah with heads of state of six Arab Gulf countries to formulate a joint strategy to counter Iran in the Red Sea.[6]

Such politically driven developments have implications for SLOC security. As the chief defender of the international rules-based order, the US has consistently sought to preserve access to the maritime commons. However, US power is increasingly under challenge from revisionist states.[7] The recent incidents in the South China Sea and the Western Indian Ocean mark a return to the days of hard military posturing in contested regions. It raises questions about the long-term safety of the important sea lanes between Asia and Africa, especially about whether or not Indo-Pacific powers are willing, and able, to stop state aggression in the sensitive littorals.

The issue is not confined merely to the geopolitics of naval power. In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, Indo-Pacific states are witnessing a decline in shipping amid a slowdown in economic activity.[8] The shipping industry faces strong headwinds, with inflationary pressures and higher energy costs weighing heavily on market sentiment.[9] Recent figures show a significant fall in regional container growth as a result of softening demand. Despite an improvement in port congestion in Europe and the US, vessel delays continue to clog ports and cram warehouses, causing widespread disruptions across regional markets. Notably, in the post-pandemic era, state capacities to ensure maritime security have significantly declined, causing concern in the shipping industry about the future of commercial operations.[10] The war in Ukraine has made things worse for trade logistics, and many countries in the region are still not willing to agree to a system of free passage and open access.[11]

This paper carries out a region-wide assessment of threats to seaborne trade in the Indo-Pacific. While SLOC security remains critical for Asian and African powers, the paper argues that geopolitics complicates maritime security cooperation in the littorals. With rising competition in the Western Indian Ocean and the Pacific, countries remain reluctant to work together in the regional commons. The capacity of states to provide security goods has been further constrained by the evolving nature of non-traditional threats. The paper surveys the security situation in the Indian Ocean and the Western Pacific and identifies obstacles that could impede the flow of maritime traffic in Asia’s sea lanes.

Choke Points in the Indian Ocean

From an Indian perspective, the space most critical to secure trade flows in the Indo Pacific is the Indian Ocean Region (IOR). The area hosts some of the world’s most important trading routes connecting West Asia and Africa with South Asia, East Asia, Europe and the Americas, and is traversed by some of the world’s heaviest trading traffic. Indeed, more than 80 percent of all seaborne trade in oil (equivalent to about one-fifth of global energy supply) passes through the IOR.[12] From a SLOC security perspective, three regions in Indian Ocean are of particular interest: the Persian Gulf/Strait of Hormuz, the Horn of Africa, and the Eastern Indian Ocean.[13]

The Straits of Hormuz

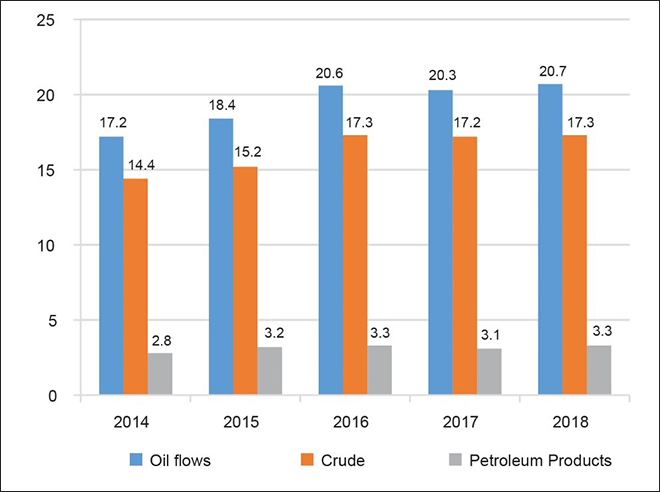

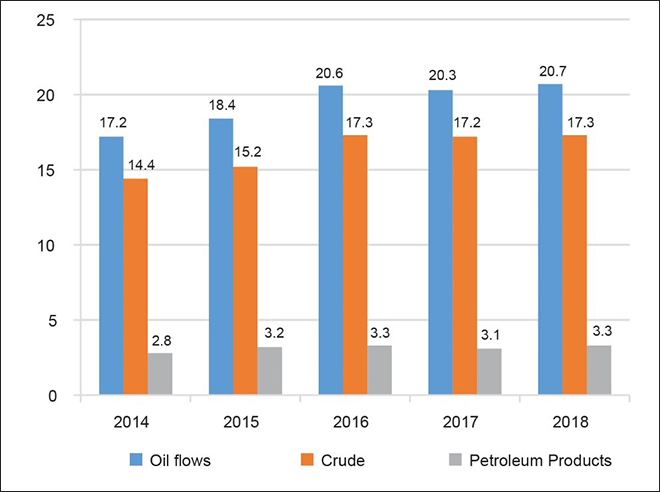

With an average daily oil flow of about 18 million barrels per day (b/d), the Strait of Hormuz is an extremely important commercial thoroughfare in Asia (see Figure 1).[14] At its narrowest point, the strait is only 21 miles wide; nonetheless, it is responsible for transporting close to one-fifth of the crude oil that is produced globally and provided by countries located in the Gulf. The strait’s shallow depth renders ships in the area prone to mine hits, attacks by missiles launched from land, and interception by fast attack craft.

Figure 1: Crude Oil Condensate, Petroleum Products through the Strait of Hormuz (2014-2018, in million barrels per day)

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration

The likelihood of a strategic confrontation in this key waterway has grown with mounting acrimony between the United States and Iran. Following the US’s withdrawal from the 2015 nuclear agreement with Iran and six other powers, Iranian officials have made open threats to close the Strait of Hormuz. In April 2019, Washington declared the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps—the most powerful military institution in the Islamic Republic—a foreign terrorist organisation, prompting Tehran to label the US as a state sponsor of terrorism.[15]

Iran-US animosity grew after Washington accused Iran of orchestrating attacks on oil tankers in the region.[16] In May 2020, a US airstrike killed Iran’s top general, Qassim Soleimani, further deepening the mistrust between Washington and Tehran. Iran’s capture of two US drones in the Red Sea in September 2022 was in seeming response to Washington’s attempts to reinforce a multinational task force to target Iranian activity in the waters around Yemen. Tehran has moved to restrict US military access in the Persian Gulf, with IRGC attack craft threatening US naval operations in the Strait of Hormuz. The Iranian air force has announced it would induct Russian Su-35 fighter jets, to counter US presence in the region.[17]

Iran’s moves to modernise its arsenal of anti-ship mines are particularly disconcerting for US officials. The IRGC navy has developed significant mine-laying capability and deployed anti-ship missile weapons on Iran’s coast, negating key US advantages in the Persian Gulf.[18] In collaboration with China, Iran has been strengthening its joint intelligence collection capabilities in the region.[19] Beijing has also undertaken, utilising a bilateral strategic agreement signed with Tehran in June 2020, to invest US$400 billion in Iran’s oil and gas and infrastructure sectors, including multiple projects on Iran’s Gulf coastline.[20]

The prospect of an Iran-induced crisis in the Persian Gulf has led transatlantic powers to expand their military presence in the zone. In 2019, Britain, supported by France, Italy, and Denmark, announced a Europe-led “maritime protection mission” to protect oil flows through the Straits and other choke points and international shipping lanes.[21] European navies have moved to operationalise a ‘coordinated maritime presence’ (CMP) concept, extending maritime operations in the North-Western Indian Ocean.[22] The emphasis has been on domain awareness exercises, analysis, and information sharing. The EU has also identified the northwestern Indian Ocean as a “maritime area of interest” (MAI), a move prompted not only by the recent events in the Red Sea, but also the war in Ukraine. As many in Europe see it, the conflict in Eastern Europe makes it imperative for European powers to secure oil flows from the Gulf region.

Horn of Africa

Less sensitive than the Persian Gulf but a hotspot, nevertheless, is the Horn of Africa. Located at the intersection of the Red Sea and the Western Indian Ocean, the region has long served as a powder keg for great-power struggles. The Horn is currently witnessing new rivalries on its shores, with Gulf states transposing internal rivalries onto a fragile region.[23] The primary fault line in the region is the split between Iran and Arab states, but an intra-Arab conflict has added to regional tensions, testing the ability of states to navigate conflict. Since 2014, when a coalition of African and West Asian countries intervened in Yemen, competition among regional players is at a peak. A recent Saudi-UAE bid to counter Iran, Turkey, and Qatar in the Red Sea has set in motion a bruising contest, with huge security implications for the region.[24]

The Gulf rivalries have triggered a scramble for military bases in the Horn region.[25] Saudi Arabia has established a military base in Djibouti, and the UAE has built major naval and air facilities at Assab in Eritrea. The latter also has a military facility at Berbera in Somaliland, from where GCC forces have been deployed to support operations in Yemen. Meanwhile, Turkey and Qatar are expanding their own presence in the Horn region with facilities in Somalia and Sudan.[26] In January 2020, there was a brief attempt by Arab and African states to engineer a reconciliation between the warring sides.[27] A Houthi attack on Marib—the Yemeni government’s last stronghold in the north—ended any hopes for an amicable settlement.[28]

The continuing instability in the Horn of Africa has implications for maritime security and regional trade flows. With African and Gulf States unable to resolve contentious issues, the Red Sea coast has witnessed increased militarisation and growing security risks. China’s military base in Djibouti has further complicated an already complex security situation.[29] Recent reports suggest the base is fully operational, with a newly constructed facility to dock and resupply large warships.[30]

State-sponsored terrorism adds another layer of complexity to the security dynamics in the Western Indian Ocean—particularly Iran’s covert support to the Somalia-based terrorist group al-Shabab. For some time now, there has been speculation that Tehran could use al-Shabab to attack the US military and other foreign forces in East Africa.[31] An attack on the Hayat hotel in Mogadishu in August 2022 demonstrated al-Shabab’s lethal ability to plan and carry out effective attacks on enemy target. The group has long focused on using ports and coastal waters to grow its presence in the region,[32] and its recent activities show it has grown in confidence and capability.

In March 2020 two speedboats piloted by members of the Mozambican group Ahlu-Sunna Wa-Jama (ASWJ)—the newest terror outfit in the Western Indian Ocean—carried out an attack on the port city of Mocímboa da Praia in the northern Cabo Delgado province. Dozens of police and military people were killed in the attack, and the insurgents took a huge stash of weapons from the military barracks in the town.[33] Five months later, ASWJ seized control of the port city. It continues to use small crafts to target islands off the coast of Mozambique.

Another security concern is the growing sophistication of terror attacks. Fourteen years after the Lashkar-e-Taiba used a regular fishing boat to enter Indian waters and carry out a devastating attack in Mumbai, terrorists have sharpened their game, inducting drone boats, floating mines, and attack craft into their toolkit. Militant groups have also become more adept at raising funds by smuggling weapons and selling goods illegally, which has helped them expand their terror activities.[34]

From a security perspective, the proximity of the Horn of Africa to the Suez Canal is a cause of worry. As the critical shipping route connecting the Mediterranean and Red Seas, the Suez Canal is vital for world trade and traffic management in the narrow canal is a challenge. A blockage caused by a massive cargo ship in March 2021 is said to have cost nearly 12 percent of global trade, holding up trade valued at over US$9 billion per day, for six days.[35] The canal is also susceptible to terror attacks. A strike on a water pumping station east of the Suez by Islamic State militants in May 2021 killed 11 security personnel.[36]

The Eastern Indian Ocean

Perhaps the most troubled spot on the eastern-end of the Indian Ocean is the Andaman Sea. In the aftermath of the India-China military clash in Ladakh in June 2020, the Eastern Indian Ocean has emerged as a flashpoint for conflict. Since the skirmish with China in the Himalayas, New Delhi has been trying to get a better hold on the difficult western approaches to the Malacca Strait.[37] A vast majority of international East-West trade, including Chinese oil shipments, container vessels and bulk cargo traffic, approaches the Malacca through the 10-degree channel between Andaman and Nicobar.

Continuing tensions along the India-China Himalayan border have prompted New Delhi to expedite plans for refurbishing military bases at the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. A proposal to construct additional facilities for warships, aircraft, missile batteries, and infantry soldiers on the strategically located islands has been greenlighted.[38] The runways at existing naval air stations are being lengthened so that large planes can land and take off, and more infrastructure is being set up for surveillance.

India’s efforts have been focused on tracking Chinese warships and submarines.[39] Since June 2020 at least, Indian warships and aircraft have been patrolling vast swathes along the choke points on the Eastern edge of the IOR. P-8I aircraft based in India’s Andaman and Nicobar Islands are on a constant watch of the seas around the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, and the Indian Navy has expanded its operational engagement with friendly navies.

China, too, has sought to expand its Bay of Bengal presence. Beijing has made significant inroads in South Asia via the Belt and Road Initiative, setting up what many see as dual-use civilian military bases.[40] China has also heightened its non-military activities in the Eastern Indian Ocean. In September 2019 an Indian warship expelled the Shiyan 1, a Chinese research vessel found intruding into the exclusive economic zone off the coast of India’s Andaman and Nicobar Islands.[41] In August 2022, another Chinese space survey and satellite tracking vessel, the Yuan Wang 3, docked in the Sri Lankan port of Hambantota.[42] Despite Indian objections, Colombo felt obliged to allow the ship to dock at its port.

China’s non-military activities in the eastern Indian Ocean, too, are a source of concern for Indian observers.[43] China’s surveillance and intelligence operations could engineer mistrust with New Delhi and lead to a conflict in the littorals. For India, a bigger danger is that Indian pressure on China in the eastern Indian Ocean could impact international traffic flows, causing regional blowback against India. Indian attempts to exploit China’s ‘Malacca dilemma’ could lead Beijing to react in unpredictable ways. [44]

The Western Pacific

The threats to maritime passage in the Pacific are no less hazardous than the challenges in the Indian Ocean. For over a decade, law enforcement agencies in the Western Pacific have been grappling with a number of threats including piracy, terrorism, criminal trafficking, illegal fishing, and arguments over the Law of the Sea Convention. Yet the most difficult of security impairments in the region are the territorial disputes in the South China Sea, and the differing perspectives over military operations in the Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs).

South China Sea / Strait of Malacca

It is widely acknowledged that the threats to maritime security in the Indo-Pacific region are most pronounced in the Western Pacific, particularly in the South China Sea (SCS). The Strait of Malacca, which connects the Indian Ocean to the SCS, is the busiest and arguably the most important sea lane in the world.[45] Only about 1.7 miles wide at its narrowest point, the Strait of Malacca is a maritime bottleneck like few others in the world. Over 25 percent of oil shipped between West Asia and the rest of the continent passes through the strait—a figure that has steadily increased as China and other regional powers have grown in population and wealth. In 2017, transits through the Malacca were as high as 84,456 (over 16 million barrels/day), a large proportion of which were oil and gas shipments bound for China, Japan and South Korea. [46] The SCS is itself a region rich in oil and gas deposits, but it is also a site of intractable sovereignty disputes, overlapping maritime jurisdictional claims, and conflicts over historical rights.[47] The Straits of Lombok and Sunda act as feeders into the SCS, and are equally critical from a SLOCs security perspective.

As China exerts its territorial claims in the South China Sea, its attempts to coerce fellow claimants in Southeast Asia have intensified over the past two years. In April 2020, Beijing ordered an administrative reorganisation of its territories in the Spratly and Paracel Islands, scaling up naval and coast guard presence in the South China Sea.[48] Beijing then closed off a swath of sea space near the Paracel Islands to enable the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Navy to conduct naval drills. In May 2020, China’s military started cross-regional mobilisation exercises that included full-scale attack and defence battle simulations in the South China Sea.[49] In the wake of the Taiwan crisis, more recently, the Shandong—the PLAN’s second aircraft carrier—held comprehensive drills in the South China Sea. It was a less-than-subtle message to the US and its regional allies that China is readying for a fight in the Pacific.[50]

Chinese aggression in waters off Vietnam and Malaysia is particularly troubling. In April 2020, the Chinese militia sunk a Vietnamese boat, and followed it up by harassing a Malaysian exploration vessel that nearly caused a standoff between the Chinese and Malaysian coast guards.[51] The US Navy responded by deploying two aircraft carrier strike groups (CBGs) in the SCS. It has since increased the frequency of freedom of navigation patrols near the China-held Spratly and Paracel islands.

For their part, Southeast Asian states have been reluctant to directly counter China. Malaysia, Indonesia and Vietnam have sought to push back Chinese aggression with quasi-legal and diplomatic means. To protest Chinese presence around Malaysia’s Luconia Shoals, the Malaysian government approached the United Nations Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf in December 2019, claiming waters beyond the 200-kilometer limit of its Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) in the northern part of the South China Sea. China immediately issued a protest note to the same commission, scaling up military presence in and around contested areas of the SCS.

Hanoi protested the 2019 sinking of a Vietnamese fishing boat by a Chinese vessel near the Spratly Islands, and was the driving force behind ASEAN’s June 2020 reaffirmation of the centrality of the 1982 UNCLOS as the basis for determining maritime entitlements, sovereign rights, jurisdiction, and legitimate interests in the South China Sea.[52] Vietnam, however, has been unwilling to use force to oppose Chinese military operations in disputed regions of the SCS. Despite its vocal criticism of Chinese assertiveness, and the PLA’s attempts to militarise China’s artificial islands in the Spratly and Paracel, Hanoi has not resisted Beijing’s uppity in the negotiations for a Code of Conduct in the SCS. The Philippines and Indonesia, too, have avoided taking a confrontational posture toward China, opting instead for a more accommodating strategy. This has only served to erode ASEAN’s ability to constrain Chinese power play in the littorals.

To be sure, China is not the only threat to the safety of maritime flows in the Western Pacific. Piracy in Southeast Asia has been rising and remains a significant hazard. The Regional Cooperation Agreement on Combating Piracy and Armed Robbery against Ships in Asia (ReCAAP) reported a total of 27 incidents in the Singapore Strait for the period January-June 2022, a significant rise from the corresponding period in 2021 when 20 incidents were recorded.[53] Many of the recent acts of piracy have been in the nature of armed robbery and are spread across the South China Sea.[54] Worryingly, the number of attacks in the Singapore and Malacca straits has steadily increased, posing a challenge to maritime traffic movement through the SLOC. Despite significant strides in the state capability to combat illegal activity in littoral waters, it has been hard to contain criminal activity.[55]

Securing the Sea Lanes

The challenges in the Indian Ocean and Pacific littorals create an imperative for collective action. As the most capable military power, the United States has been at the forefront of the cooperative mission. The Combined Maritime Forces (CMF), a US-led naval coalition of 33 nations, is the leading security player in the western Indian Ocean, and it has largely ensured safe passage of commercial shipping through the region over the past two decades.[56] The CMF is assisted in its endeavours—especially in counter-piracy missions—by the European Naval Force (EUNAVFOR) Somalia, and other regional maritime forces from India, Japan and China.

In recent years, however, the US dependence on oil from West Asia and, by extension, its reliance on the regional SLOC has rapidly diminished. Since the US ‘fracking’ boom in the 2010s, the country had turned into a net exporter of oil products. Washington has since been contemplating a reduction in US security presence in the Persian Gulf.[57] Some analysts are of the view that this is an unlikely scenario. After all, US allies are highly dependent on West Asian oil; with China’s growing footprint in the Western Indian Ocean, Washington, optimists aver, will likely continue deploying US warships in the region to protect its geopolitical interests.[58]

US allies and partners, however, have been preparing for the contingency of reduced US interest in the IOR. New Delhi, in particular, has stepped up its presence in the Indian Ocean to protect its interests in the area.[59] As a key security provider and first responder in the region, India has sought a partnership with France, Australia and Indonesia to hedge against the possibility of falling US interest in the affairs of the IOR. Chinese assertiveness in Asia has resulted in the revival of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue or Quad—a multilateral group comprising India, the US, Japan and Australia. After a decade-long hiatus, the four nations resumed the dialogue in November 2017 and have significantly expanded their security engagement since then.[60]

Yet, the Indian Navy (IN) faces a dilemma: it is not an active player in the Persian Gulf and the South China Sea. India’s security endeavours in the Western Indian Ocean and the Western Pacific are confined to antipiracy patrols, protection of merchant shipping, and bilateral exercises with regional navies. While it joined the US-led Combined Maritime Forces as an ‘associate partner’ in the Western Indian Ocean in August 2022, the IN’s role is limited to countering non-traditional challenges such as armed robbery, drug trafficking, marine pollution, and illegal fishing.[61] Crucially, in the eastern Indian Ocean and parts of the Arabian Sea, where the IN is a significant player, the China threat is yet to crystallise. India’s security role in the regional SLOC remains mostly limited to the Eastern Indian Ocean.

The European Union, too, has been at pains to define its security role in contested areas of the Indo-Pacific. Despite the recent announcement of ‘coordinated presence’ and ‘maritime areas of interest’, European focus in the Indian Ocean and the Pacific has been capacity building (providing legal assistance and training), maritime domain awareness (MDA), and operational coordination among select East African and archipelagic states. In 2020, the EU took the initiative a step forward by announcing an extension of the ‘critical maritime routes in the wider Indian Ocean’ (CRIMARIO) program to the Eastern Indian Ocean and Southeast Asia.[62] EU officials even recognise the need for integrated law enforcement in contested regions. The EU, however, remains reluctant to play an active role in the Persian Gulf and the South China Sea. Despite their support for a Rules-Based Order in a Free and Open Indo-Pacific, European states largely prefer to stay out of Asia’s contested littorals. France and the UK are the only two European countries to have maintained a modicum of military presence in the Western Pacific.[63]

Two multilateral groupings have contributed significantly to sea lanes security in the Western Pacific: The Regional Cooperation Agreement on Combating Piracy and Armed Robbery against Ships in Asia (ReCAAP) and the Malacca Strait Patrol Network.[64] To their credit, ASEAN navies and coastguards have sought to integrate operations and enhance tactical coordination in the fight against piracy and transnational crime. Unfortunately, the benefits of cooperation do not extend to traditional areas of security, in particular the challenge of an aggressive China in the Western Pacific.

Regional Security Arrangements

Many had expected the Indian Ocean Naval Symposium (IONS), and the Code for Unplanned Encounters at Sea (CUES)—a 2014 agreement between 21 Indo-Pacific powers that sets guidelines for unexpected encounters between naval ships and aircraft at sea—to impose tacit curbs on Chinese assertiveness in the littorals.[65] Such hopes have been belied. While the IONS has remained silent on Chinese aggression in the South China Sea, the CUES appears powerless to counter Chinese power projection in the Western Pacific. The latter is a non-binding agreement, and does not govern interactions between non-military agencies.[66] Moreover, CUES does not apply to areas within 12 miles of the disputed features in the SCS, leaving the Chinese coast guard and maritime militias free to posture and intimidate rivals.[67]

Similarly, Indian Ocean Rim Ocean (IORA) countries have shown little appetite for countering China’s Indian Ocean manoeuvres. China is a dialogue partner of the IORA, and many member countries depend on Beijing for development aid. With decision-making in IORA premised on the principle of consensus, member states have been reluctant to raise issues that are likely to generate controversy or impede regional cooperation efforts. Some Bay of Bengal states have even been looking at giving IORA dialogue partners, including China, a stronger voice within the association.[68]

For its part, India has stressed the need for an inclusive regional security architecture. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s ‘Security and Growth for All’ (SAGAR) approach emphasises consideration of the stakeholders’ interests in maritime commons. India’s aim is to foster a climate of trust and transparency; respect for international maritime rules and norms by all countries; peaceful resolution of maritime security issues; and more security cooperation.[69] Yet in the aftermath of the China-India conflict in Ladakh, New Delhi has seemed less sure about whether SAGAR, and the Indo-Pacific cooperative framework, include cooperation with China. India’s strategic community remains convinced that China poses a threat to Indian security interests, though Beijing has so far refrained from directly challenging India in the Indian Ocean.

A Risk-Based Approach

Some maritime experts advocate a risk-based approach to analyse maritime security challenges in the SLOC. They emphasise the importance of the common perception of risk and vulnerability in the littoral, as well as the imperatives for collective action.[70] The key questions for such an assessment include: Do states agree over common threats? If yes, then are maritime powers willing to come together to fight security challenges collectively? Although theoretically sound, a risk-based approach to SLOC security runs into the difficulty of identifying the precise nature of threats, and of quantifying the costs and benefits of cooperation. While states largely agree about the challenges they collectively face in the maritime domain, many countries remain uncertain about the nature of the risks to national security. In some countries, the maritime impulse is tempered by a consideration of political factors and the persistence of a continental mindset. This creates some hesitation among the decision-making elite to sanction hard security cooperation in the littorals.

The dilemma about the use of force at sea pertains not only to China’s expansive power projection, but also to challenges like climate change, where the hazards to the SLOC are yet to be precisely defined. The military leadership in many countries is often unclear about the extent of acceptable cooperation. Overall, Navies are aware that they must work together to secure the maritime commons. To what degree, to what specific ends, and at what cost are some questions that remain unexplained, however.[71]

Shifting Trade Patterns

The pandemic has added a new layer of complexity to the protection of the SLOC. Following the massive economic fallout of COVID-19, there are growing attempts at reorganising supply chains—this could potentially cause shifts in the flow of maritime commerce. The US, for example, would like to bring home supply chains from China, and has broached the idea of the need for a group of friendly nations in Asia that could help produce essential commodities.[72] The idea to decouple from China, as a way of reducing economic dependence on Beijing, has widespread support in countries outside of the US, including among a great number of Asian states. Businesses are being encouraged by governments in the region to look for alternative sources for components of their supply chain outside of China in order to diversify the risks associated with concentration and reduce the likelihood of disruption in the event of exogenous shocks. Some countries, like India, are pushing for a model of self-reliance that would reduce the impact of Chinese companies on their economies.[73] Other governments, including many that have for long supported international trade, have also put up barriers to business.

However, decoupling from China is not going to be easy. The pandemic reaffirmed China’s important role in sustaining international trade. Accounting for around one-third of global trade, China is showing the resilience and determination to remain the so-called ‘factory of the world’. Not surprisingly, despite attempts to diversify away from China, international businesses have found it hard to shift their sources of supply and production elsewhere. Those countries that see themselves as possible alternatives to China as production sites, do not have enough people nor the right kind of population to replace the Chinese workforce.[74] In the hypothetical scenario that these states shift value chains away from China, it is not likely that Beijing will respond with military force. China is itself extremely reliant on Asian sea lanes for the provision of resources and energy. The country is home to the shipping industry, and controls the largest proportion of the world’s total shipping fleet (at around 15 percent). With Chinese energy demands estimated to double over the next two decades, the country’s reliance on regional sea routes is only expected to increase in the coming years. There is less likelihood that the PLAN will obstruct international traffic in the sea lanes that run through Asia.

The shifting nature of the geopolitical landscape in Asia is the third reality that analysts and policymakers must consider. The competition for influence and leverage has resulted in a move towards stronger partnerships and alliances. Growing pressure on China from the US and its Southeast Asian allies may force Beijing to reconsider its assertive posture. On current trends, China’s manufacturing sector could witness a loss of jobs. In time, Beijing could feel compelled to work together with neighbours to secure the SLOC; the Chinese leadership could even recognise the right to free navigation in the South China Sea. At the same time, domestic instability inside China, and growing uncertainties vis-à-vis Taiwan, may push the Chinese Communist Party to adopt a more belligerent military posture.

An aggressive China does not, however, mean a warlike situation in the Indo-Pacific region. Given its own stakes in Asian trade and regional development, Beijing would likely desist from enforcing an undeclared blockade in the South China Sea. Given the PLA’s contributions to regional security and global governance—in terms of peacekeeping, disaster recovery, counterterrorism, and antipiracy operations—China is likely to keep geopolitical tensions below the threshold of conflict, balancing between political ends and economic imperatives. Even so, domestic politics inside China and in other Southeast Asian countries could play a part in determining the direction of strategic competition in Asia. If nationalism-fueled political ambitions exceed development needs, Asian powers could find themselves embroiled in conflict. On the other hand, a greater expectation of growth and development would result in a greater willingness among countries to cooperate.

Conclusion

The concept of a ‘rules-based order’ neatly encapsulates the widely felt need for security in the maritime commons, particularly with regard to the security of the SLOC. Yet, maritime security dynamics in a post-pandemic world are likely to be fluid, and cooperation between states could well be driven by the imperatives of economics and national well-being. With growing demand for resources and energy, and declining capacity among the region’s states to police the SLOC, stakeholders may have little option but to pool resources to collectively secure the maritime commons. With commercial and military uses of Asia’s sea lanes inextricably linked, countries are likely to work together to protect the sea lanes, regardless of their political differences and power differentials.

Growing contestation between world powers will be a complicating factor, in particular the possibility of a US-China conflict in the South China Sea. Even absent a military conflict, a trade war between the two countries could result in a reorientation of Asian value chains. A shift in supply lines away from China could restructure maritime trade in ways that might be detrimental for the regional security order. The pandemic and the impact of the war in Ukraine could also lead the region’s states to act in erratic ways, especially if shifting patterns of trade and economics are found to favour particular countries. Even so, Asian powers have tangible incentives to cooperate in a post-pandemic world.

For now, the threats to maritime trade remain largely unchanged, even if security capacities appear to be shrinking. An intensification of non-traditional security challenges, particularly the threat of maritime terrorism, could result in a strong drive for cooperation. Yet geopolitics is likely to reign supreme. Assuming geopolitical trends remain manageable, a coordinated approach in the commons is the best way forward for the Indo-Pacific.

Endnotes

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PDF Download

PDF Download

PREV

PREV