-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

PDF Download

PDF Download

Parjanya Bhatt, “Revisiting China’s Kashmir Policy”, ORF Issue Brief No. 326, November 2019, Observer Research Foundation.

India maintains that the question of Kashmir is a bilateral matter between New Delhi and Islamabad. Yet over the years, there are countries that have used the Kashmir issue for their own interests. China, for one, has not had a concrete policy on the question of Kashmir, choosing instead to capitalise on the issue for its own agenda. Despite the inconsistencies, however, Beijing’s policy has historically been inclined towards Pakistan. This has become more clear over time, despite China’s vacillation as well as its cartographic strategies – showing J&K as part of either India or Pakistan, or else as an independent territory.[1]

Following India’s decision to abrogate the special constitutional status of J&K in August 2019, China has once again become vocal on the larger Kashmir issue involving India and Pakistan, issuing different statements over the course of several weeks.[2] Immediately after India repudiated Article 370, Beijing called on India and Pakistan to resolve the Kashmir issue bilaterally,[3] while adding a caveat that India was undermining China’s territorial sovereignty.[4] On 16 August 2019, upon the request of Pakistan, China called on the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) to hold a closed-door informal meeting on the issue.[5] (China is a permanent member of the UNSC.) Owing to India’s diplomatic efforts, all the 15 members of the UNSC were given briefings by New Delhi, and this UNSC meeting largely remained symbolic as Pakistan received support only from China.[6]

It remains to be seen how China will continue to exploit India’s internal matters to its diplomatic, military and geographical advantage, and how New Delhi responds to the same.

In the early 1950s, China held a neutral stance[7] regarding the Kashmir conflict.[8] During his visit to India in December 1956, Premier Zhou Enlai stated, “The Kashmir question is an outstanding question between the two nations and we hope that it will be settled satisfactorily….There is no dispute between the countries that cannot be settled.”[9]

In September 1957, China announced the completion of a road across the Aksai Chin plateau – claimed by India as its territory and by China as part of Western Tibet.[10] New Delhi reacted by sending military reconnaissance patrols and a memo to Beijing asserting its sovereign rights over the region. China rejected India’s claim.[11] The friction between the two nations was exacerbated in the 1960s. China began building pressure on India on the Ladakh border by deploying personnel of its People’s Liberation Army (PLA) to the area; this would eventually lead to clashes with Indian security forces.[12] At the same time, China tacitly started to advocate war on behalf of Kashmir’s right to self-determination, stopping short of calling it a “war of national liberation”[13] and echoing Pakistan’s position that it was for the people of Kashmir to decide which nation to be part of.[14]

In July 1961, Premier Zhou asked India’s Foreign Ministry officials: “Can you cite any documents to show that we have ever said Kashmir was not part of India?” At that time, therefore, China’s position was that it had no claim on Kashmir.[15] However, this must be read in the context of the meeting between Zhou Enlai and then Indian Vice President Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan in April 1961. In that conversation, China—in order to justify its physical control of Tibet and Xinjiang—raised the Kashmir issue but without calling India an occupying force.[16] Beijing also gave a veiled threat to New Delhi to avoid taking a position on Tibet and Xinjiang and China’s occupation of the territories.[17]

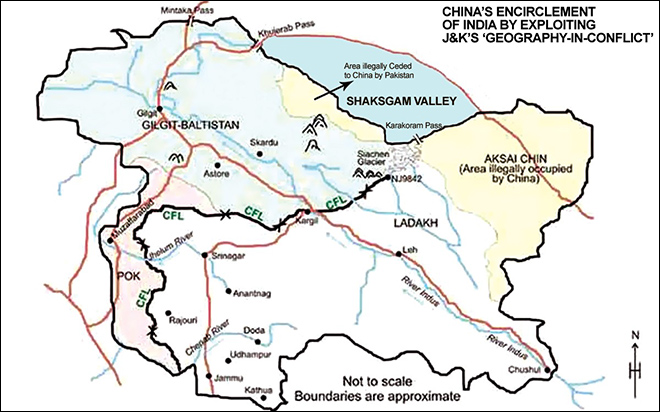

The 1962 war with China led to its gaining control of a sizeable land mass in Leh and Ladakh in J&K; at that point, it became a stakeholder in the Kashmir issue. A year later, the China-Pakistan border treaty of March 1963,[18] which transferred the Shaksgam Valley, just northwest of the Siachen glacier, to China, allowed it to enter PoK and establish direct access to Afghanistan and come close to India’s western and northern borders. In 1964, in support of Pakistan, Beijing called for a UN-supervised plebiscite in Kashmir;[19] the plebiscite would not materialise as Pakistan appeared to have lost the enthusiasm.[20] The next year, Pakistan waged another war against India over Kashmir which received Beijing’s tacit military and diplomatic support reminiscent of the Sino-Pakistani friendship that underpinned the Aksai Chin episode and also the 1962 war.[21]

The Sino-Pakistani ties strengthened further in the 1970s. During the 1971 India-Pakistan war, China’s role was a blend of “tempered support, gentle scolding and steely pragmatism.”[22] After Pakistan’s defeat, China rushed to help rebuild its military forces.

In the 1980s, under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping and in accordance with his push for economic reforms, China sought to improve relations with its neighbours. On the Kashmir issue, Beijing reverted to its old position that it was a matter best left between India and Pakistan.[23] This was also attributed to then Minister of External Affairs Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s historic visit to China in 1979.[24] Although Beijing emphasised the Simla Agreement of 1972[a] and endorsed UN intervention on the Kashmir issue , it tacitly maintained a pro-Pakistan slant.[25]

Map 1: Aksai Chin Plateau and the Shaksgam Valley

In the 1990s, Beijing gave indications that it would start to cede to India’s diplomatic lobbying; in response to Pakistan-sponsored terrorism in Kashmir, official statements from Beijing did not refer to any UN intervention, but reiterated bilateral negotiations between India-Pakistan as the only way to address the issue. In the early ‘90s, Chinese Premier Jiang Zemin also advised Pakistan to put the Kashmir issue on the backburner and allow ties with India to improve through trade; but to no avail, as cross-border terrorism inside Kashmir reached its peak.[26] Later, in May 1998, following India’s Pokhran tests,[b] Beijing once again demanded that the Kashmir issue be referred to the UN. While India justified the tests at the international level by referring to China’s threat, Beijing termed India’s actions as “hegemonic” and blamed India for inciting military tension in South Asia.[27] China also broadened its covert assistance to Pakistan’s missile programme and military modernisation.[28] China’s call for international intervention to resolve the Kashmir issue also continued during the Kargil conflict in 1999.[29]

In an unlikely turn of events following the Kargil conflict and subsequent attack on the Indian Parliament in 2001,[c] New Delhi and Islamabad engaged in a peace dialogue over Kashmir in 2004. The dialogue failed, however. In 2005, China returned to its pre-1998 position that the Kashmir issue was a bilateral one between India and Pakistan.[30]

However, in 2006, from the World Social Forum in Karachi,[31] later in 2009[32] and again in 2014, the Hurriyat Conference[d] invited China to resolve the Kashmir issue.[33] The Hurriyat hoped that a rising China would bring India and Pakistan together, but it received little positive response. However, Beijing did not completely fail the separatists. In effect questioning India’s locus standi over Kashmir, it began issuing stapled visas to Kashmiris.[34] In 2010, it refused to grant a visa to Gen. Baljit Singh Jaswal, the head of the Indian Army’s Northern Command in J&K; this showed a radical shift in China’s Kashmir policy. The move was followed by China referring to J&K as a “disputed territory”.[35] India lodged a protest with Beijing while stating, “By denying visa to Gen. Jaswal, China has questioned the status of J&K as it relates to the country’s sovereignty.”[36] Beijing continued to rebuff New Delhi even after External Affairs Minister S. M. Krishna visited China in April 2010 and expressed India’s sensitivity to the Kashmir issue and the matter of the stapled visas.[37]

After all the back-and-forth on the Kashmir issue, China’s true intentions would soon become clearer. The PLA was intent on establishing a foothold in PoK to control the region militarily and diplomatically. Nearly 11,000 Chinese military troops were deployed to PoK, suggesting that Pakistan had given de facto control of the territory to China.[38] Rejecting the media reports about the military presence, Beijing described Gilgit-Baltistan as “Northern Pakistan” and J&K as “India-controlled Kashmir”.[39] In doing so, China not only questioned India’s locus standi on PoK, it also legitimised Pakistan’s claim on the territory.

Another report then followed shortly, describing the presence of some 7,000 non-combat soldiers in PoK comprising construction, communication and engineering units of the PLA.[40] This, when looked through the prism of the Tibet Military Command (TMC) under the PLA’s Western Theatre Command (WTC), has serious significance as the said military command is dedicated to carrying out armed operations against India.[41] This specifies the command’s ability to improve PLA’s military resource management, mobilisation of forces and preparation for combat operations in high-altitude areas of Aksai Chin and Arunachal Pradesh.[42] The WTC is also trained to carry out operations in conjunction with the PLA Navy, allowing it to pose serious challenges for the Indian security forces in J&K.

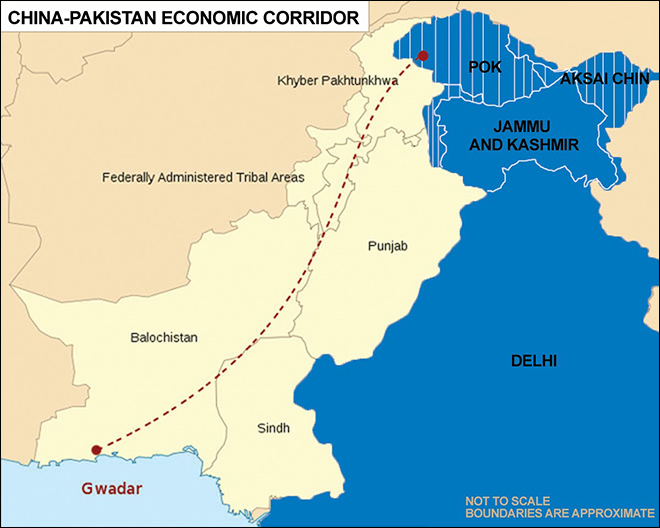

Beijing’s apparent oscillation on the Kashmir issue, at least in terms of the publicly stated foreign policy stance, has helped China derive short-term and medium-term gains. Such has also positioned China in an advantageous position vis-à-vis India over the long term. This became clear with China’s announcement of its One Belt One Road (OBOR) project in 2013, since renamed the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). BRI’s flagship project, the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) passing through PoK has raised some serious and legitimate concerns for India.

While forging favourable economic engagements with India, China has simultaneously been strengthening its military ties with Islamabad. Beijing clandestinely supplies Pakistan with nuclear and missile technologies[43] to counter India’s prominence in the South Asian region.

Indeed, China has utilised its alliance with Pakistan and the Kashmir conflict to constrain India’s emergence as a potential competitor to its own rise in global power dynamics.[44] While such efforts began in 1959—with China and Pakistan building the Karakoram Highway (KKH) passing through PoK[45] —followed by the signing of the 1963 border agreement,[46] the pushback appears to be culminating into the CPEC.[47]

Map 2: The Karakoram Highway

In 2012, there were speculations about Pakistan leasing the region of Gilgit-Baltistan in PoK to China for 50 years.[49] While these speculations have been refuted by both countries, the possibility cannot be ruled out entirely,[50] especially in light of the massive investments Beijing has committed to the CPEC. Reports have already emerged of the Pakistan government leasing out land in Gilgit to China for construction of projects under CPEC and providing military security cover to them.[51]

Indeed, the CPEC is central to the hegemonic pursuits of China in South Asia. The selection of PoK for developing the strategically important CPEC yields multidimensional advantages that go beyond the obvious economic benefits. It will expand China’s geographical reach inside Pakistan in a way that allows the PLA to come extremely close to India’s northern and western flanks. In other words, the CPEC will give China access to the Arabian Sea and develop an alternate route for its critical energy imports and other resources,[52] and acquire yet another gateway to Afghanistan.

Map 3: China’s corridor for power projection in South Asia

Even as China and Pakistan do not share land borders, their military and diplomatic collusion against India—and China’s own geopolitical priorities in the region—have brought them together in the Indian state of J&K. With its presence in PoK, China is safeguarding its own political and strategic interests as well as those of Pakistan. Adopting an approach that does not involve conquering territories through military campaigns, China, through a strategic partnership with Pakistan is investing billions of dollars to expand the KKH, and build mega transport infrastructure, oil and gas pipelines, railway lines[54] and feeder roads in PoK. These infrastructure projects have helped China consolidate its control over PoK and the strategic Shaksgam Valley, to tie India down in the region. The Chinese road network through Shaksgam, which also connects the KKH with the Tibet-Xinjiang Highway has led to encirclement of J&K from three sides.[55] While the feeder roads connect crucial military complexes based in China and Pakistan, Gilgit provides the natural cover to military facilities like missile bases and tunnels – enhancing their joint capacity – and making it possible for them to launch pincer movements against India.[56]

The border dispute between India and China involves three parts: the western sector, middle sector, and eastern sector. The western sector, which pertains to the Johnson Line proposed by the British in 1865, shows Aksai Chin as part of Indian state.[57] China did not raise any objections to this demarcation till the 1950s, when it started changing its position and emphasised that the McDonald Line drawn in 1893, which placed Aksai Chin in Chinese territory was correct.[58] Ladakh[e] too, or large portions of it, has been shown in official Chinese maps as part of China. These cartographic aggressions and border incursions have dominated the discourse between India and China, hindering the resolution of their border issues despite several rounds of talks and various confidence-building measures.

In April this year, China’s Ministry of Commerce did issue a map showing both Ladakh and Aksai Chin, as well as Arunachal Pradesh, as parts of India. However, the same map—released at the 2nd BRI Summit in Beijing—also shows India as part of the BRI, despite India’s consistent stand on the issue.[59]

Map 4: BRI map showing J&K and Arunachal as part of India

Later, in August, in response to India’s redrawing of J&K’s map which declared Ladakh as a union territory, China sided with Pakistan. Beijing brought up the issue of Aksai Chin at the UNSC and asserted its sovereign right over the region.[61] It also issued a warning to India indicating disruption of stability along the India-China border.[62] In a measured response, New Delhi made it clear that redrawing of J&K’s map was India’s internal matter and will not change the status quo along the Line of Actual Control (LAC) and the international boundaries.[63] However, following the restructuring of J&K, one can expect China to continue with its cartographic aggression and strengthen its military posturing inside Indian territory in Ladakh and other areas.

While India’s rise as an emerging power remains a main concern for China, the bigger obstacle to Beijing’s power projection in South Asia is the presence of Islamic extremists in the Afghanistan-Pakistan (Af-Pak) region and their interaction with the Uyghur Muslims in China’s restive province of Xinjiang. Given the deteriorating situation in the Af-Pak region, Beijing fears a percolation of fundamentalist forces into the Xinjiang province via PoK. By using the extremism argument in the context of Xinjiang, China feels it can justify its presence in PoK. China has selectively boosted certain counter-terror efforts while enlisting strategic support from Pakistan-based terror organisations.[64] The aim of such approach is to obtain wide national consensus across Pakistan’s political spectrum in its favour and simultaneously immunise Chinese interests against perceived security and political threats emanating from within Pakistan.[65]

Map 5: China’s encirclement of India by exploiting J&K’s ‘Geography-in-Conflict’

The BRI and the CPEC need stability; and terror groups operating from the Pakistani soil pose danger to these strategic and economic assets. China’s soft corner for terrorists along the CPEC is in stark contrast to Beijing detaining thousands of Uyghur Muslims under the pretext of counter-terror operations.[67] However, on India-centric terrorism emanating from Pakistan, Beijing has tended to shield its ally. Ever since Pakistan-sponsored terrorism began in Kashmir, China has conveniently looked the other way. While the repeated terrorist attacks in J&K have attracted condemnation from much of the international community, China is the only Permanent-5 nation of the UNSC that has preferred to take a non-committal position on the issue of cross-border terrorism. China, by seemingly falling in line with the rest of the world to support India on declaring Jaish-e-Mohammad (JeM) chief Masood Azhar as a global terrorist under the UNSC’s 1267 Sanctions Committee, has neither done any favour to India nor displayed any significant departure from its policy on terrorism directed against India by Pakistan. Days before the SCO summit in Bishkek in June 2019, Beijing came out in direct support of Islamabad, reiterating that no single country should be targeted for terrorism.[68]

The 10-year delay on the Masood Azhar issue showcased China’s power politics vis-à-vis India. Besides international pressure, the reversal of China’s stand could also be attributed to two other factors: the relentless diplomatic and political heavy-lifting done by the Modi government;[69] and the 2016 surgical strikes and Balakot air raids, which demonstrated India’s military assertiveness in the occupied territory and the realisation that China’s friendship with Pakistan may cost the CPEC.[70] However, China’s close ties with JeM and other Pakistan-supported terror outfits—which safeguards its economic and geostrategic interests in PoK—is unlikely to end anytime soon.[71] According to reports, some 500,000 Chinese nationals are expected to be living in the Gwadar port city by 2023.[72] China is therefore likely to continue to use the terror groups within the PoK to keep India busy along the LoC and inside the Kashmir Valley.

For India, this has also raised serious concerns about China’s role in case hostilities break out with Pakistan.[73] The presence of the Chinese PLA within the illegally occupied territories of PoK to its northeast and Aksai Chin to its northwest has raised a security dilemma for India of fighting a two-front war.

The state of J&K is India’s natural strategic space and, historically, a diplomatic battleground. India’s response to Pakistan’s military overtures have been fitting and disciplined, and not directed towards taking the occupied territories back. Over the years, China has sought to limit India’s response by entering into territorial agreement with Pakistan, issuing selective criticism of and support to terrorism, and building infrastructure in occupied territories.

As India revoked the special constitutional status of J&K and declared Ladakh as a Union Territory,[74] China yet again adopted a pro-Pakistan stance[75] by referring to Kashmir as a “disputed territory”.[76] For now, Beijing’s actions may remain limited to issuing pro-Pakistan statements, helping its efforts to internationalise the Kashmir issue and by moving forces along the Ladakh border in J&K to keep up the pressure on India. It remains to be seen how, in the long run, China’s policy would address India’s assertion of sovereignty.

Two scenarios are likely to emerge from the recent developments: First, by amending the country’s Constitution, the possibility of Pakistan formally annexing Gilgit-Baltistan as its fifth province cannot easily be dismissed. The area is located at the extreme north of PoK and is currently treated as a separate geographical territory by Pakistan. The move would establish a firm grip of the Pakistani state over the territory and embolden China to officially move the PLA into the area.

Second, China may move to officially annex the Shaksgam Valley. Under the 1963 border agreement with Pakistan, China agreed that the said area will be traded depending on the result of the settlement New Delhi and Islamabad reach on the Kashmir issue. However, in the light of the recent move by India, the formal annexation of the Shaksgam Valley by China cannot be ruled out. Both these possibilities will be in disregard of India’s sovereignty.

During the visit of External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar in August 2019—days after the redrawing of the political map of J&K by India—China raised objections on the issue of Ladakh and asked how it would impact the India-China border. This will lead to new difficulties for India in the long term.

[a] The Simla Agreement contains a set of guiding principles, mutually agreed to by India and Pakistan, which both sides would adhere to while managing relations with each other. These emphasise: respect for each other’s territorial integrity and sovereignty; non-interference in each other’s internal affairs; respect for each other’s unity, political independence; sovereign equality; and abjuring hostile propaganda. The following principles of the Agreement are, however, particularly noteworthy:

i) A mutual commitment to the peaceful resolution of all issues through direct bilateral approaches.

ii) To build the foundations of a cooperative relationship with special focus on people-to-people contacts.

iii) To uphold the inviolability of the Line of Control in Jammu and Kashmir, which is a most important CBM between India and Pakistan, and a key to peace.

[b] The Pokhran-II tests were a series of five nuclear bomb test explosions conducted by India at the Indian Army’s Pokhran Test Range in May 1998.

[c] Terrorists belonging to two Pakistani terror organisations – Lashkar-e-Toiba and Jaish-e-Mohammad carried out a suicide attack on the Indian Parliament on 13 December 2001. The attack led to the deaths of six Delhi police personnel and two Parliamentary security service. In retaliation, Indian security forces gunned down five terrorists. The attack led to increased tensions between India and Pakistan, and a military stand-off in 2001-02.

[d] The All Parties Hurriyat Conference (APHC) was formed on 31 July 1993 as a political platform of the separatist movement. It was an extension of the conglomerate of parties that had come together to contest Assembly polls against a National Conference-Congress alliance in 1987 — an election that was widely alleged to have been rigged.

[e] Ladakh is critical for maintaining Indian presence on the Siachen Glacier as it provides physical approach to the frozen battlefield, connecting to the rest of the country. West of the Siachen glacier, across the Saltoro Ridge, lies Pakistan-occupied Gilgit and Baltistan. East of it lies China-occupied Aksai Chin. With a presence on the Siachen glacier, India has managed to prevent China and Pakistan from linking up.

[1] ‘China Removes Map Depicting Jammu & Kashmir, Arunachal as Part of India‘, 28 April, 2019, Accessed: 12 Nov, 2019. Also check.

[2] Kashmir issue should resolved via dialogue between India, Pakistan: China’, The Economic Times, 26 July, 2019. Accessed: 14 August, 2019. Also refer, ‘Kashmir internationally recognised disputed territory: Chinese envoy’, and ‘Unilateral move will incur risks for India’.

[3] ‘China calls on India, Pakistan to resolve disputes through talks as Qureshi arrives for talks’, 9 Aug, 2019, Accessed: 12 Nov, 2019

[4] ‘Beijing Says India’s Kashmir Move Undermines China’s Sovereignty, Gets Support from ‘Friend’ Pakistan’, 6 Aug, 2019, Accessed: 13 Nov, 2019

[5] ‘Pakistan gets backing only from China at UNSC meeting on Kashmir: Report’, 16 Aug, 2019, Accessed: 13 Nov, 2019

[6] Elizabeth Roche, ‘India thwarts lobbying by China, Pakistan at UN Security Council’, livemint, 17 August, 2019.

[7] Jingdong Youn, ‘China’s Kashmir Policy’, China Brief Volume: 5 Issue: 19, September 13, 2005, Accessed: 12 August, 2019

[8] Santosh Singh, ‘China’s Kashmir Policy’, World Affairs, Summer 2012 (April-June) Vol. 16, No. 2, Pg. 102

[9] ibid

[10] John Garver, Evolution of India’s China Policy, ed. Sumit Ganguly, Oxford University Press, 2010, Pg. 90

[11] Hongzhou Zhang and Mingjiang Li, ‘Sino-Indian Border Disputes’, ISPI, Analysis No 81, June 2013, Accessed: 13 Nov, 2019.

[12] ‘Record of Conversation between Zhou Enlai and VicePresident Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan‘, April 21, 1960. Accessed: 21 October 2019

[13] John Garver, ‘China’s Kashmir Policies’, India Review, Vol: 3, No: 1, January 2004, 1-24, Pg. 8

[14] ibid

[15] Shri Ram Sharma, India-China Relations, 1947-1971′, Discovery Publishing House, 1999, Pg. 79,

[16] ‘Record of Conversation between Zhou Enlai and VicePresident Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan’, April 21, 1960, op. cit.

[17] ibid

[18] I-Wei Jennifer Chang, ‘China’s Kashmir Policy and Crisis management of South Asia’, Peace Brief, United States Institute of Peace, February 2017, Pg. 1-4

[19] Santosh Singh, op. cit.

[20] B L Sharma, ‘The Kashmir Story’, 1 April, 2003, Accessed: 24 Nov, 2019

[21] Santosh Singh, op. cit.

[22] Andrew Small, 2015, op. cit. Pg. 16

[23] John Garver, January 2004, op. cit.

[24] Ibid, Also refer: Sudheendra Kulkarni, ‘The one who reached out to China: On Atal Bihari Vajpayee’, 11 September, 2018, Accessed: 15 June, 2019

[25] John Garver, ‘Protracted Contest: Sino-Indian Rivalry in the Twentieth Century’, University of Washington Press, 2001

[26] ‘The Subcontinental Menu’, 6 June, 2018, Accessed: 20 October, 2019

[27] John Garver, ‘The restoration of Sino-Indian comity following India’s nuclear tests’, The China Quarterly, No. 168, December 2001, Pg. 865-889

[28] Ibid Pg. 874, For details, refer, John Garver, ‘Protracted Contest: Sino-Indian Rivalry in the Twentieth Century’, University of Washington Press, 2010

[29] Santosh Singh, op. cit.

[30] Santosh Singh, op. cit. Pg. 108

[31] https://www.satp.org/satporgtp/countries/india/states/jandk/terrorist_outfits/Hurriyat_tl.htm

[32] ‘China has direct links with Kashmir, Says Mirwaiz’, 20 November, 2009, Accessed: 16 June, 2019

[33] Naseer Ganai, ‘Hurriyat leaders look to China for resolution on Kashmir’, 22 February, 2014, Accessed: 20 October 2019

[34] Asgar Qadri, ‘Story behind a stapled Chinese visa’, 8 November, 2013, Accessed: 17 June, 2019

[35] Jayadeva Ranade, ‘The age of region’, 13 January, 2010, Accessed: 17 June, 2019

[36] ‘India dismisses report of confiscation of material in China’, 29 August, 2010, Accessed: 20 June, 2019

[37] ‘China rebuffs India, says its policy on J&K visas unchanged’, 26 October, 2010, Accessed: 22 June, 2019

[38] Selig S. Harrison ‘China’s Discreet Hold on Pakistan’s Northern Borderlands’, 26 August, 2010, Accessed: 22 June, 2019

[39] Saibal Dasgupta, ‘China calls PoK ‘northern Pakistan’, J&K is ‘India-controlled Kashmir‘, 2 September, 2010, Accessed: 24 June, 2019

[40] Chidanand Rajghatta, ‘Pak had ceded control of Gilgit in PoK to China: US scholar’, 9 September, 2010, Accessed: 29 June, 2019

[41] Kevin McCauley, ‘Snapshot: China’s Western Theatre Command’, Publication: China Brief Volume: 17 Issue: 1, 13 January, 2017, Accessed: 21 October 2019

[42] ‘China elevates military command along Indian border: Report’, PTI, 12 July, 2018, Accessed: 21 October, 2019

[43] Andrew Small, 2015, Pg. 54

[44] John Garver, 2001, op. cit. Pg. 217

[45] Andrew Small, 2015, op. cit.

[46] ‘China-Pakistan Border Agreement’, International Legal Materials, Vol. 2, No. 3, May 1963, Pg. 541-542

[47] Andrew Small, 2015, Pg. 181

[48] Zaid Haider, Yale Global Online, Clearing Clouds Over the Karakoram Pass, 29 March, 2004, accessed 12 August 2019.

[49] The Economic Times, ‘Pakistan considering proposal to lease Gilgil-Baltistan to China: US think tank’, 11 February, 2012, Accessed: 10 July, 2019

[50] Priyanka Singh, ‘Repositioning Pakistan occupied Kashmir on India’s policy map’, IDSA, No. 62, October 2017, Pg. 82, 83

[51] Amir Karim Tantray, ‘Pakistan government leases land in Gilgit to China’,24 March, 2012, Accessed: 24 Nov, 2019

[52] Ian Storey, ‘China’s Malacca Dilemma’, China Brief, Vol. 6, Issue. 8, The Jamestown Foundation, Accessed: 13 August, 2019

[53] http://chinamatters.blogspot.com/2016/05/the-worlds-most-dangerous-letters-are.html

[54] Senge H Sering, ‘Expansion of the Karakoram Corridor: Implications and Prospects’, IDSA Occassional paper No. 27, Pg. 9, Accessed: 6 July, 2019

[55] Senge H Sering, op. cit.

[56] Senge H Sering, op. cit.

[57] Mihir Bhonsle, ‘Understanding Sino-Indian Border Issues: An Analysis of Incidents Reported in the Indian Media’, ORF Occasional Paper February 2018, Accessed: 22 October, 2019

[58] http://ias4sure.com/wikiias/gs2/india-china-border-disputes/

[59] Dipanjan Roy Choudhury, ‘2nd BRI Summit under way in Beijing: China gets map right on Jammu & Kashmir, Arunachal Pradesh’, The Economic Times, 26 April 2019. Accessed: 19 October, 2019

[60] https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/defence/china-removes-bri-map-that-showed-arunachal-jk-part-of-india/articleshow/69070354.cms?from=mdr

[61] Dipanjan Roy Choudhury, ‘China raked up status of Aksai Chin at UNSC informal session’, 20 August, 2019. Accessed: 23 October, 2019

[62] ‘Ladakh UT involves our territory: China Foreign Minister to Jaishankar’,13 August, 2019, Accessed: 23 October, 2019

[63] ibid

[64] Mathieu Duchatel, ‘The terrorist risk and China’s policy toward Pakistan: Strategic reassurance and the ‘United Front’, Journal of Contemporary China, 2011, Sept, Pg. 543-561

[65] ibid

[66] Prabhash K Datta, “Gilgit-Baltistan: Story of how region 6 times the size of PoK passed on to Pakistan,” India Today, 5 April 2018, accessed 13 August 2019.

[67] ‘China says it has arrested 13,000 ‘terrorists’ in Xinjiang’, 18 March, 2019. Accessed: 8 July, 2019

[68] ‘SCO meeting agenda on counter terrorism not aimed at “targeting” any country: China’, 10 June, 2019. Accessed: 8 July, 2019

[69] ‘Elizabeth Roche, ‘US, France and UK give ultimatum to China to lift hold on Masood Azhar: Report’, 12 April, 2019. Accessed: 12 July, 2019

[70] Rakesh Krishnan, ‘Move on, Masood: Why China threw its favourite terrorist under the bus’, 2 May, 2019, Accessed: 11 July, 2019

[71] Ayjaz Wani, ‘China’s real intentions behind its ‘technical hold’ on Masood Azhar’, ORF, 21 February, 2019, Accessed: 14 August, 2019

[72] Murtaza Ali Shah, 500,000 Chinese professionals expected in Gwadar by 2023’, The News, 21 October 2017, Accessed: 14 August, 2019

[73] Priyanka Singh, ‘Gilgit Baltistan Between Hope and Despair’, IDSA, No. 14, March 2013, Pg. 65-82, Accessed: 16 July, 2019

[74] India Today, Article 370: China says opposed to Ladakh as Union Territory’, 6 August, 2019, Accessed: 14 August, 2019

[75] Times of India, ‘Pakistan say will move to UN security council with China’s support over Kashmir’, 10 August, 2019, Accessed: 14 August, 2019

[76] India Today, ‘Kashmir internationally recognised disputed territory: Chinese envoy’, 8 August, 2019, Accessed: 14 August, 2019

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Parjanya was a Research Fellow with ORF Mumbai chapter. His research focuses on terrorism and the security situation in the state of Jammu and Kashmir. ...

Read More +