-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

PDF Download

PDF Download

Image Source: Rethinking the relevance of existing credit rating agencies to BRICS

I. Introduction

Global growth, which experienced a slowdown in recent years, is expected to witness a trend reversal in 2017—projected at 2.7 percent, higher by 0.4 percentage points than what was recorded last year. This increase is mainly due to renewed confidence in the emerging and developing market countries, whose economic growth is projected at 4.6 percent for 2018 as compared to 1.8 percent in the advanced economies. Such momentum is likely to pick up pace because of recovery in commodity exports and continued strong domestic demand for commodity imports. In this paper, focus is on the emerging economies of Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa, or the BRICS regional bloc that accounts for 22.7 percent of the world’s gross domestic product.[i] These countries have large investment requirements, especially for developing infrastructure, for which they are dependent on global credit markets and investors. Their access to credit and investments, in turn, relies on the ‘rating’ they obtain—a ‘credit rating’ is an opinion about the overall creditworthiness of the issuer, that is, whether the issuer would be able to meet the debt obligation within the stipulated time.

At present, the global market for providing credit ratings is dominated by three agencies, namely, Standard and Poor’s (S&P’s), Moody’s, and Fitch. They assign ratings to entities (governments, central banks, and corporates) all over the world, based on both the public and private information provided by the issuers to the agencies. The rating agencies charge substantive fees from issuers to rate their debts and financial instruments. As economies and corporations increasingly need to borrow capital from abroad, the role of credit rating agencies has also expanded multi-fold. International corporations consider a rating essential for making investment decisions as it enables them to distinguish among debt markets across the world.

The rating agencies have been criticised not only for “fraudulent” ratings but also for “intensifying” the economic crisis. For example, the impact of the global financial crisis of 2008-09 on the United States (US) was worsened by the erroneous ratings given by international credit rating agencies to assets which were already considered as “toxic” but were given AAA rating (indicating the best quality financial instruments). These agencies have also downgraded ratings of emerging market economies and are also criticised for what is being seen as their “biased” ratings.[ii]

For India, its sovereign credit rating[iii] is just one notch above the ‘speculative grade’ category despite signs of robust growth. The reform measures adopted by India in various sectors have been inadequate in obtaining higher ratings. The “bias”, critics say, is clearly seen in how these agencies rate their home country, the US. The rating and rating outlook for the US remained unchanged during the last presidential elections in the country, as global credit rating agencies seemed to have accounted for the effect of the fiscal stimulus plans of the Trump administration while ignoring the resultant increase in the national debts, which would put a downward pressure on the GDP growth rate.

The financial markets in emerging market economies have always drawn the attention of global investors as they offer higher returns than the advanced economies. According to the World Bank Treasury, the debt of emerging countries—at nearly US$ 6.3 trillion in 2013—is almost half the size of the US Treasury markets, which is the world’s biggest and most liquid market.[iv]

In October 2016, during the 8th BRICS Summit held in Goa, BRICS countries set up an expert group to explore the possibility of setting up an independent rating agency[v] based on market principles, thus developing on the idea that first emerged during the 2015 BRICS Summit held in Ufa, Russia. The idea was also pushed by the frequent experiences of rating downgrades and, at the same time, encouraged by the confidence of global investors in the debt markets of BRICS economies. A BRICS credit rating agency would cater to the needs of the issuers, especially corporates that get a lower rating because of the low sovereign rating obtained by their home country. Such a rating agency would evaluate issuers/entities on their relative strengths within emerging markets and would use an emerging market rating scale – an intermediate scale between national and global ratings scales. This paper describes the issues levelled on global credit rating agencies, against the backdrop of the macroeconomics of emerging market economies. It provides specific policy recommendations for global credit rating agencies and explores the potential of an independent credit rating agency set up by BRICS for BRICS.

II. Emerging Market Economies: Macroeconomic Trends

Emerging market economies have a significant role in driving global growth. After all, they account for nearly one-third of the global output and are home to 75 percent of the world’s population and poor.[vi] According to the World Bank’s January 2017 report, Global Economics Prospects, emerging market economies are expected to grow at an average 4.2 percent in 2017, followed by 4.6 percent average growth in 2018. This is in contrast to the average growth forecast of 1.8 percent for the advanced economies for 2018.[vii] The rapid pace of economic growth in emerging economies is expected to contribute 1.6 percentage points to global growth this year, accounting for the strongest contribution of about 60 percent to global growth since 2013.[viii] This growth is attributed to increased capital inflows to emerging markets caused by record-low interest rates prevalent in the advanced economies upto November 2016. This, along with the stabilisation of commodity prices in the emerging economies, resulted in increased demand for their financial assets. The political and policy uncertainties in advanced economies (among them, the Brexit referendum, the US elections, and restrictive monetary policy) have caused the shifting of investments towards emerging markets – nearly US$ 9 billion were invested in emerging market equity funds in the six weeks ended August 10, 2016.[ix]

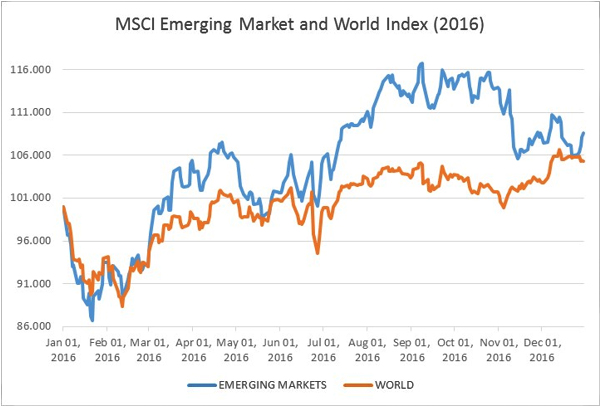

Among the emerging economies, BRICS are among the biggest, contributing 22.7 percent[x] to the global gross domestic product (GDP) in 2016. To sustain their present real GDP growth momentum of 5.5 percent (2016), BRICS economies require ample investments. They have taken several initiatives—such as setting up multilateral development institutions like the New Development Bank and Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank—to cater to the infrastructure needs of the region. The BRICS economies, especially China and South Africa, are highly vulnerable to financial shocks and uncertainties in the advanced economies—which are their major trading partners, after all—and these events could create ripple effects in terms of suppressing investment growth in the medium and long term. Prior to November 2016, the emerging markets attracted a lot of equity funds and the MSCI emerging market index provided annual returns of 11.55 percent[xi] between January 2016 and December 2016 as compared to MSCI world index returning 7.28 percent for the same period. Figure 1 provides the MSCI emerging market index values and MSCI world index values for the calendar year 2016.

Figure 1

Note – The base year of index values is 100. The emerging market index measures the equity market performance in 23 emerging markets in the world. The world index measures the equity performance of developed markets. Both the index are free float-weighted.

In 2016, the emerging market economies outperformed the returns on stocks of the developed market due to a number of factors, including steadier growth in China, stabilisation of Brazilian and Russian economies after deep recessions, and political disruptions in the US and UK. However, due to rising global bond yields and the appreciation of US dollar under Trump, financial markets in emerging economies faced sudden currency depreciations, portfolio outflows, and slowing debt issuance. At present, some companies in the consumer-related and information technology sectors in the emerging markets are likely to offer better returns.[xii]

III. State of Play of Credit Rating Agencies

Credit rating agencies have an important role in providing investors a comprehensive analysis of the risks associated with debt securities issued by corporates, and sovereign entities such as national governments and central banks. The risk ratings indicate the issuer’s creditworthiness, which is determined by the ability and willingness of the issuer to repay the loans and debt within the stipulated time. The ratings enable corporations and governments to raise capital in the foreign capital markets at a low cost. Rating the debt instruments of a corporate entity is a common phenomenon undertaken by global and national credit rating agencies. However, corporates cannot have ratings above the sovereign rating of their country; this has serious implications for firms in times of a sovereign rating downgrade. The demand for sovereign credit ratings has increased dramatically over the past few decades, especially by the governments that have had a history of debt defaults.[xiii] These ratings provide governments access to the international bond markets and also bridge the existing information asymmetry between investors and issuers, thereby reducing the problems of adverse selection.[xiv]

The global credit ratings market is dominated by three agencies – Standard and Poor’s (S&P’s), Fitch, and Moody’s, all based in the US and together account for a market share of 95 percent.[xv] Sovereign credit ratings by S&P’s began in 1929 when Poor’s Publishing and Standard Statistics (a predecessor to S&P’s) rated US-denominated bonds but issued by other national governments, known as sovereign Yankee bonds. The bonds rated by Poor’s were issued by 21 western governments (Europe, North America and South America) as well as in the Asia-Pacific (Australia, Japan, China). Before S&P’s, Moody’s was a pioneer in rating the sovereign debt instruments. Fitch entered the credit rating market in 1975 and soon established itself as the third biggest player. Until the 1980s, the agencies mostly rated the advanced countries and a few emerging economies. However, by December 2006, about 131 countries were rated by one or more of the three agencies, out of which 65 percent were developing countries[xvi] and the rest were high-income economies.[xvii]

The credit ratings issued by the agencies are provided on a letter scale, ranging from AAA to C. The highest and safest credit quality gets a rating of AAA whereas the investment/issuer with highest default risk is assigned a rating of C. (See Table 1)

Table 1. Rating scale for three main credit rating agencies

| Credit Quality | Standard and Poor’s | Fitch | Moody’s |

| Investment grade | |||

| Highest | AAA | AAA | Aaa |

| Very high | AA+ | AA+ | Aa1 |

| AA | AA | Aa2 | |

| AA- | AA- | Aa3 | |

| High | A+ | A+ | A1 |

| A | A | A2 | |

| A- | A- | A3 | |

| Good | BBB+ | BBB+ | Baa1 |

| BBB | BBB | Baa2 | |

| BBB- | BBB- | Baa3 | |

| Speculative grade | |||

| Speculative | BB+ | BB+ | Ba1 |

| BB | BB | Ba2 | |

| BB- | BB- | Ba3 | |

| Highly speculative | B+ | B+ | B1 |

| B | B | B2 | |

| B- | B- | B3 | |

| High default risk | CCC+ | CCC+ | Caa1 |

| CCC | CCC | Caa2 | |

| CCC- | CCC- | Caa3 | |

| Very high default risk | CC | CC | Ca |

| C | C | C | |

Source: Adapted from a study by Ratha, D. et al. (2010); Standard and Poor’s, Moody’s Investor Service, and Fitch Ratings

The local and national credit rating agencies also provide risk assessments for the financial instruments issued by corporates and governments, which indicate credit quality and worthiness of the issuer within a country. A credit rating on a national scale is primarily used by domestic investors, whereas global investors are interested in global rating scales. The global and national rating scales are different in their scope and coverage and are not directly comparable. However, the national rating scales can be translated into global rating scales (in foreign currency) through various methodologies. For example, the domestic rating agency in India (CRISIL) adopts a distinct methodology to map global and national rating scales by comparing default rates, transition rates, and financial medians of CRISIL and S&P. It is noteworthy that any changes in the global ratings would have an impact on the quality of national scale ratings once these two ratings are mapped.[xviii] The domestic investors of any country rely more on national scales for credit assessments as these provide a wider coverage of entities and corporates in local markets. Moreover, there are only a few entities in emerging economies that are assigned ratings on a global scale. The national scale ratings allow for better comparisons amongst similar entities within the country and address the needs of the specific national financial markets. BRICS have several regional rating agencies that either have a joint venture with or are wholly owned subsidiaries of the global rating agencies. Some of the domestic rating agencies in the BRICS region are Fitch Ratings Brazil Ltd., Global Credit Rating Co. in South Africa, Dagong Global Credit Rating Co. in China, Expert Rating Agency in Russia, and CRISIL Ltd. in India.

Credit Rating Process and Business Model

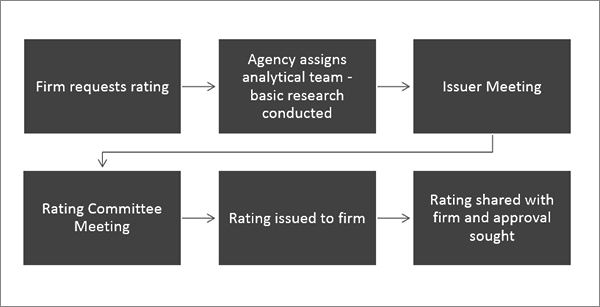

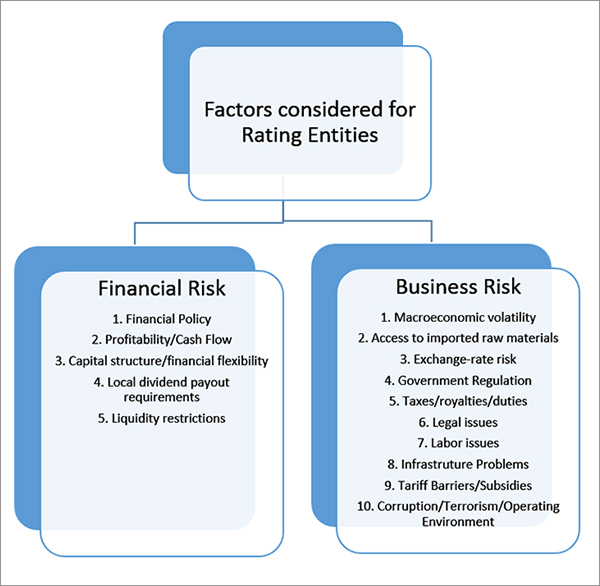

The global credit rating agencies use a sophisticated rating criteria for the debt instruments (both short-term and long-term) of the corporates. The agencies use various qualitative (business risk)[xix] and quantitative (financial risk)[xx] factors to assess corporates’ overall capacity to meet their financial obligation. The global rating scales analyse the credit profile of the corporates around the globe using the same rating methodology – the industry risk and firm’s competitive position is assessed in tandem with the company’s financial risk profile and policies.[xxi] Figure 2 shows the corporate debt rating process of S&P’s. The process is largely similar for the other global credit rating agencies.

The rating process for a corporate starts with its request to the rating agency to assign a rating to its debt instruments using the sets of background materials such as financial statements, description of operations, etc. submitted by it. Subsequently, the agency assigns an analytical team (led by industry analyst) to the issuer who conducts basic research and evaluation of the credit profile of the company. The team then meets with the corporate management (issuer meeting) in order to review in detail the company’s operating and financial plans. After the issuer meeting, the rating committee consisting of five to seven voting members meets with the industry analyst assigned to the specific issuer who finally provides a rating recommendation. Once the rating is decided, the firm is notified of the rating and its approval is sought for making the rating public.

Figure 2. Corporate Debt Rating Process of Standard and Poor’s

The credit ratings assigned to the sovereigns are determined by both quantitative (economic and financial)[xxii] and qualitative (political)[xxiii] factors. The credit rating agencies assign different weights to the economic and political factors, the details of which are not publicly available. This lack of transparency in the rating methodologies adopted by these agencies has led to suspicion among the market participants.

The rating process of a sovereign is similar to a corporate except for the variables used for risk assessment and assigning ratings. The rating process starts with the sovereign entering into a formal agreement with the international credit rating agency. The sovereigns then share primary economic and financial data with the agency. Subsequently, a team of two or more analysts from the credit rating agency visits the country for three to four days in order to meet with the finance ministry and central bank representatives, including experts in areas of politics and economic policy. The analysts then prepare a report for the rating committee providing their recommendations and suggestions, which are then assessed by the committee and eventually a rating is assigned.

However, there is no exact formula or methodology to factor in the economic and political considerations into the rating. The rating is based on the internal discussions of the committee, which are kept confidential. Due to the highly subjective nature of credit ratings, it can be inferred that the entire process is influenced by perceptions and judgments of the analysts specific to political and economic health of the sovereigns.[xxiv]

The big three credit rating agencies follow an ‘issuer-pays’ business model, wherein the issuer of financial instruments pays the agency for initial and ongoing ratings. These ratings are later made available to the public free of cost. In contrast, there exist a small number of rating agencies such as Egan-Jones and Rapid Ratings that follow ‘subscriber-pays’ business model, in which the investor of the bond is required to pay for the ratings. Due to growing criticism around the issuer-pays model because of the problem of conflict of interest,[xxv] particularly after the financial crisis of 2007-08, there are discussions about adopting the ‘subscriber-pays’ model instead. However, this model too has its advantages and disadvantages that need to be considered before making any such shift.

The big three international credit rating agencies, all based in the United States, have an oligopoly in the global credit rating market and significantly influence the access of sovereigns and corporates worldwide to international credit markets. All these credit rating agencies are profit-driven and derive revenues from the fees paid by the issuer. In 2010, the profit margin of the big three agencies was recorded at 45 percent for S&P’s, 38 percent for Moody’s and 30 percent for Fitch Ratings.[xxvi] The oligopolistic market structure of these agencies has received severe criticism from policymakers and experts as it restricts new entry, and results in low evaluation quality due to lack of competition. However, the role of regulation in promoting oligopoly of the global credit rating market cannot be ignored. For example – the regulatory restrictions in the United States has limited entry of new firms in the credit rating market.[xxvii] There are also concerns raised by the governments of different countries regarding the biased nature of sovereign ratings towards their home country (where the agency is headquartered). These US-based agencies have been criticised for downgrading the ratings of many European countries (like France, Austria, Greece, and Ireland), which aggravated the Euro-sovereign debt crisis of 2009. The government of the home country does influence the rating decisions of the committee, which is clearly expressed by the statement in 2013 by S&P’s that the fraud lawsuit filed against it by the US government is in retaliation for its decision in 2011 to downgrade the country’s AAA credit rating.[xxviii] Moreover, the analysts involved in the rating process might have vested interests in the bank or country that is being rated. Every year, the three global credit rating agencies spend thousands of dollars on lobbying efforts directed at securing favourable financial legislation and protecting its significant presence in financial markets.[xxix]

There are also instances of rating downgrades in emerging market economies, particularly BRICS. India, for example, received a rating of ‘Baa3 with stable outlook’ from Moody’s and ‘BBB-‘ from S&P’s and Fitch in 2016—far below the ratings received by other emerging nations (Israel, Chile) and some European countries (Italy, Belgium) that are highly indebted. The Indian government officials are concerned about the country’s lower rating despite it clocking an annual growth rate of over six percent and gaining improved ranking in the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business Survey.[xxx] Brazil and Russia also experienced sharp downgrades in their ratings amidst domestic political turmoil and rising expenditures. The sovereign credit rating for Brazil was cut down to the ‘junk’ category – debts rated below the investment grade – by the three global rating agencies in 2016[xxxi] due to high fiscal deficit and inflation, along with the government’s failure to introduce major reforms such as raising taxes and lowering interest rates. Russia’s sovereign rating also suffered a downgrade[xxxii] in 2015 owing to decelerating economic growth caused by falling oil prices and US’ sanctions on Russian actions in Ukraine. Regular instances of rating downgrades for emerging economies have encouraged the BRICS bloc to initiate plans to set up its own independent regional credit rating agency. This rating agency would benchmark risks on an emerging market scale (an intermediate scale between local and global credit rating scale), which is expected to benefit investors around the world, especially in emerging markets, by channeling funds appropriately between sovereign and corporate debts.[xxxiii]

Moreover, emerging market economies criticise global rating agencies because they tend to follow a similar methodology to rate debts of entities in both emerging and developed countries. Suarez (2002) argues that an asymmetry emerges while assessing the performance of banks in emerging countries. The rating agencies and analysts assume that a set of financial indicators and ratios that are suitable for evaluating banks in developed economies would be applicable to emerging economies as well.[xxxiv] However, there must be an alternative set of financial indicators that takes into consideration distinct features of economies as they differ significantly in their degree of financial deepening and development.[xxxv] Further, the corporate rating criteria report of S&P’s shows that the criteria employed by the agency emphasises the local characteristics of every economy – be it developed or emerging markets. The agency claims to take into consideration various business and financial risk factors, along with the country risk factor (which assumes an added importance in case of emerging market economies) to arrive at a specific rating. The variation in ratings between emerging and developed economies is solely the result of existing differences in risks and reforms in these economies. The rating agencies do factor in diverse national considerations while rating countries around the globe; however, it expresses its ratings on a unique single scale to facilitate easier comparisons among issues of equivalent credit quality for debt holders.

Figure 3 – Factors considered by Standard and Poor’s for rating entities (private and government) in Emerging and Developed Market Economies

Credit Ratings of Developed vs. Emerging Countries

The pattern of sovereign ratings widely varies between advanced and emerging economies. Table 2 shows that almost all emerging countries (Brazil, Russia, India, Indonesia, Philippines) have a rating just above the speculative grade, which is in stark contrast to the ratings of the developed countries (United States, United Kingdom). Recent media reports say the UK experienced a downgrade in its rating post-Brexit, with Fitch downgrading the rating from AAA to AA in June 2016 and further down to AA+ in the next month (citing slowdown in short-term growth).[xxxvi] However, the US maintained a stable outlook even during the presidential elections in November 2016 for reasons cited by agencies’ analysts such as substantial credit strength possessed by the country, including a large flexible economy, and the status of the dollar. It is known that any changes in the government policies and economic variables tend to affect the stability of the economy but this has to be viewed in terms of the currency strength. For instance, if India is compared with the US, any external shock is likely to have greater adverse repercussions for India.

One of the reasons provided by analysts for lower rating or outlook assigned to emerging and developing countries is that there is lack of provision of comprehensive and timely economic information on various rating parameters.

The literature reveals that sovereign credit rating has an impact on the ratings of the corporates as well. This phenomenon seems to hold for emerging and developing economies that have a relatively low sovereign rating due to significant capital account restrictions and high political risk.[xxxvii] The correlation between sovereign and corporate credit rating is quite high for developing than developed economies. This implies that any incident of downgrading of sovereign rating would be more harmful for firms in developing than developed countries.

Table 2: Sovereign Credit Ratings for Developed and Emerging Economies issued by the Big Three rating agencies, March 2012-March 2013

| Countries | March 2012 | March 2013 | ||||

| S&P, outlook | Moody’s, outlook | Fitch, outlook | S&P, outlook | Moody’s, outlook | Fitch, outlook | |

| Brazil | BBB, stable | Baa2, positive | BBB, stable | BBB, stable | Baa2, positive | BBB, stable |

| Russia | BBB, stable | Baa1, stable | BBB, positive | BBB, stable | Baa1, stable | BBB, stable |

| India | BBB-, stable | Baa3, stable | BBB-, stable | BBB-, negative | Baa3, stable | BBB-, negative |

| China | AA-, stable | Aa3, positive | A+, stable | AA-, stable | Aa3, positive | A+, stable |

| South Africa | BBB+, stable | A3, negative | BBB+, stable | BBB, negative | Baa1, negative | BBB, stable |

| United States | AA+, negative | Aaa, negative | AAA, stable | AA+, negative | Aaa, negative | NA |

| United Kingdom | AAA, negative | Aaa, negative | AAA, stable | AAA, negative | Aa1, stable | AAA, negative |

| Australia | AAA, stable | Aaa, stable | AAA, stable | AAA, stable | Aaa, stable | AAA, stable |

| Hong Kong | AAA, stable | Aa1, positive | AA+, stable | AAA, stable | Aa1, positive | AA+, stable |

| Singapore | AAA, stable | Aaa, stable | AAA, stable | AAA, stable | Aaa, stable | AAA, stable |

| Indonesia | BB+, positive | Ba1, stable | BB+, positive | BB+, positive | Baa3, stable | BBB-, stable |

| Philippines | BB, stable | Ba2, stable | BB+, stable | BB+, positive | Ba1, stable | BB+, stable |

Source: The Guardian Datablog

Issues with International Credit Rating Agencies

V. Recommendations for Credit Rating Agencies

The ratings assigned by credit rating agencies significantly influence the outlook of investors internationally. It is of utmost importance especially for developing countries to get rated because these ratings serve as benchmark to attract foreign investments.

BRICS credit rating agency: Is it a feasible policy move?

The idea of setting up an autonomous credit rating agency for BRICS economies emerged during the BRICS Summit held in Ufa, Russia in 2015. The global credit rating agencies have been severely criticised for long for their unjust and biased rating downgrades for emerging and developing market economies. However, there is a lot to be put in place in terms of planning, financing, methodology, regulations, and legal structure to implement a plan as ambitious as a BRICS rating agency. The foremost factor to be considered is to build partnership with each and every member country of the BRICS bloc and obtain consensus on establishing the rating agency. Indeed, China has already expressed concerns about the credibility of the proposed BRICS credit agency on several occasions. The politics within BRICS need to be worked out for this plan to move forward. For example, China is not willing to accept an agency that is spearheaded by India.[xl] The power dynamics between China and India pose a serious challenge to the establishment of the new credit rating agency. Moreover, cooperation amongst the Russia-China-India trilateral is another essential factor that requires due contemplation. China might not be willing to share decision-making authority with the other BRICS members. It is essential to clearly specify who will be playing a leading role in establishing the BRICS credit rating agency. A comprehensive standard of operating procedures for the member countries is likely to facilitate financial cooperation among them.

Another risk for the BRICS credit rating agency is to build a market standing and acceptability of its rating scale amongst investors. For this, the BRICS rating agency should garner support from an established rating agency (preferably located in any of the BRICS economies) which has extensive experience in the emerging and developing markets. Support from a prominent rating agency would enable the new rating agency to develop a sound understanding of emerging market credits and create a robust credit rating methodology through exchanges of technical and managerial skills.[xli] However, choosing an ideal location for operations and harmonising regulations of the BRICS credit rating agency are critical and contentious factors.

The proposed rating agency also needs to find the best business model and rating methodology to provide a reliable credit opinion to the issuers and investors. Every business model, whether issuer-pays or investor-pays, has its own advantages and disadvantages, but it solely depends on the rating agency to effectively manage the inherent problem of conflict of interest. Also, for a credible and reliable opinion, it is suggested that the shareholders of the BRICS rating agency comprise of members from development banks, financial institutions and agencies in the region, along with some multilateral institutions.[xlii] There has to be a clear demarcation between shareholders and management of the proposed credit rating agency. This would thus limit the control of the rating agency by a single country. Moreover, the credit rating committee must not include shareholders to ensure that analysis and rating decisions are free of bias and influence by any institution or country.

The acceptability of the rating scale adopted by BRICS rating agency by investors, cooperation among the member countries, and unbiased credit opinions are critical to the success of the proposal to set up a credit rating agency for BRICS.

Endnotes

[i] Author’s calculation using World Economic Outlook Database published by IMF, GDP at current market prices in US$ billion for 2016.

[ii] “China’s Finance Minister accuses credit rating agencies of bias,” South China Morning Post, April 16, 2016, accessed May 2, 2017, http://www.scmp.com/news/china/economy/article/1936614/chinas-finance-minister-accuses-credit-rating-agencies-bias.

[iii] Sovereign credit ratings rate the debt instruments issued by governments or sovereign entities. In other words, these ratings reflect a country’s willingness and ability to repay its sovereign debts. For further details refer to Butler and Fauver, 2006, http://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/30137801.pdf.

[iv] Daniela Klingebiel, “Emerging Markets Local Currency Debt and Foreign Investors – Recent Developments,” 2014, The World Bank Treasury.

[v] Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, “Goa Declaration at 8th BRICS Summit,” October 16, 2016, http://www.mea.gov.in/bilateral-documents.htm?dtl/27491/Goa+Declaration+at+8th+BRICS+Summit.

[vi] World Bank Group, “Global Economic Prospects, January 2017 Weak Investment in Uncertain Times,” 2017, Washington, DC: World Bank.

[vii] International Monetary Fund, “World Economic Outlook,” October 2016 https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2016/02/pdf/c1.pdf.

[viii] World Bank Group, see n. vi.

[ix] Morgan Stanley, “Emerging Markets: It’s how, not when,” accessed February 1, 2017, http://www.morganstanley.com/ideas/emerging-market-stocks.

[x] Author’s calculation using World Economic Outlook Database published by IMF, GDP at current market prices in US$ billion for 2016.

[xi] Author’s calculation using MSCI Emerging Market and World Index Data. https://www.msci.com/end-of-day-history?chart=regional&priceLevel=41&scope=R&style=C¤cy=15&size=36&indexId=13.

[xii] Leslie Shaffer, “Mark Mobius: This is how to play emerging markets in 2017,” CNBC, December 21, 2016, http://www.cnbc.com/2016/12/21/mark-mobius-this-is-how-to-play-emerging-markets-in-2017.html.

[xiii] Cantor, R. and F. Packer, “Sovereign Credit Ratings,” Current Issues in Economics and Finance, 1:3, (1995), New York: Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

[xiv] Adverse Selection is a term coined by George Akerlof in 1970 (for details see “The market for lemons,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 54). The problem of adverse selection arises when one party to a transaction has more information (generally about the quality of the product) than the other party.

[xv] Council on Foreign Relations, “The Credit Rating Controversy,” 2015, CFR Backgrounders.

[xvi] This relates to the older definition of developing countries as provided by the World Bank. The countries with gross national income below US $ 11,905 are considered as developing countries. http://www.iugg2015prague.com/list-of-developing-countries.htm.

[xvii] Ratha, D. et al., “Shadow Sovereign Ratings for Unrated Developing Countries,” World Development (2010), accessed December 8, 2016, doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2010.08.006.

[xviii] CRISIL, “Translating Global Scale Ratings onto CRISIL’s Scale,” 2007.

[xix] Business risk factors include industry characteristics, competitive position of the company (marketing, technology, efficiency, regulation) and management policies. For more details see figure 3.

[xx] Financial risk factors include financial characteristics, financial policy, profitability, capital structure, cash flow protection and financial flexibility. For more details see figure 3.

[xxi] Standard & Poor’s, “Corporate Ratings Criteria,” http://regulationbodyofknowledge.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/StandardAndPoors_Corporate_Ratings_Criteria.pdf.

[xxii] For sovereigns, economic and financial factors include GDP per capita, real GDP growth, inflation, fiscal balance, default history and external debt and balances.

[xxiii] Political factors include assessment of stability, transparency and predictability of the political institutions, including the government’s policies.

[xxiv] Bruner, C. and R. Abdelal, “To Judge Leviathan: Sovereign Credit Ratings, National Law, and the World Economy,” The Journal of Public Policy, 25:2 (2005), 191-217, Cambridge University Press, UK.

[xxv] Conflict of interest means that the issuer of the financial instruments who pays for a specific rating might demand a more favorable evaluation, which could later misguide the investors.

[xxvi] Kotios, A., G. Galanos and S. Roukanas, “The Rating Agencies in the International Political Economy,” Scientific Bulletin – Economic Sciences, 11:1 (2012).

[xxvii] John Ray, “The Negative Impact of Credit Rating Agencies and proposals for better regulation”, (2012), SWP Working Paper FG 1, 2012/Nr. 01, Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, Berlin.

[xxviii] Jonathan Stempel, “S&P calls federal lawsuit ‘retaliation’ for U.S. downgrade,” Reuters, September 3, 2013, accessed November 24, 2016, http://www.reuters.com/article/us-mcgrawhill-sandp-lawsuit-idUSBRE98210L20130903.

[xxix] Dan Eggen, “S&P and others lobby government while rating its credit”, The Washington Post, August 10, 2011, accessed April 26, 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/the-influence-industry-sandp-and-others-lobby-government-while-rating-its-credit/2011/08/09/gIQANbEs6I_story.html?utm_term=.81ae67058829.

[xxx] “India’s Annoyance With S&P Rating Highlights Need for BRICS Credit Rating Agency,” Sputnik International, November 3, 2016, accessed February 2, 2017, https://sputniknews.com/business/201611031047045140-india-standard-and-poors-rating-highlights/.

[xxxi] Paula Sambo and Filipe Pacheco, “Brazil Credit Ratings Cut to Junk by Moody’s,” Bloomberg, February 24, 2016, accessed February 2, 2017, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-02-24/brazil-downgraded-to-junk-by-moody-s-with-negative-outlook.

[xxxii] Anna Andrianova and Ksenia Galouchko, “Russia Credit Rating Is Cut to Junk by S&P for the First Time in a Decade,” Bloomberg, January 26, 2015, accessed February 2, 2017, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-01-26/russia-credit-rating-cut-to-junk-by-s-p-for-first-time-in-decade.

[xxxiii] At present, 65 percent of emerging market funds are invested in sovereign debt and remaining 35 percent are corporate debt issuances. Export-Import Bank of India (EXIM Bank), “Research Paper on setting up of a rating agency by BRICS,” June 2016 (unpublished).

[xxxiv] Liliana Rojas-Suarez, “Rating Banks In Emerging Markets: What Credit Rating Agencies Should Learn From Financial Indicators,” (2002), Institute for International Economics Working Paper No. 01-06.

[xxxv] Ibid

[xxxvi] Everett Rosenfeld, “UK credit ratings cut: S&P and Fitch downgrade post-Brexit vote,” CNBC, June 27, 2016, accessed November 25, 2016,http://www.cnbc.com/2016/06/27/sp-cuts-united-kingdom-sovereign-credit-rating-to-aa-from-aaa.html; Avaneesh Pandey, “Global Sovereign Credit Rating Downgrades Set to Hit Record High, Fitch Says”, International Business Times, July 7, 2016, accessed November 25, 2016,http://www.ibtimes.com/global-sovereign-credit-rating-downgrades-set-hit-record-high-fitch-says-2389789.

[xxxvii] Borensztein, E., K. Cowan, and P. Valenzuela, “Sovereign ceilings ‘lite’? The impact of sovereign ratings on corporate ratings in emerging market economies,” (2007), 1–32, IMF Working Paper 07/75, International Monetary Fund.

[xxxviii] Robin Wigglesworth, “Emerging markets in credit ratings call”, Financial Times, June 7, 2012, accessed April 28, 2017,https://www.ft.com/content/91985856-ab34-11e1-a2ed-00144feabdc0.

[xxxix] Gonzalez et. al., “Market Dynamics Associated with Credit Ratings – A Literature Review,” (2004), Occasional Paper Series No. 16, European Central Bank, ISSN 1725-6534 (online).

[xl] Asit Ranjan Mishra, “China not in favour of proposed Brics credit rating agency”, Livemint, October 14, 2016, accessed April 27, 2017, http://www.livemint.com/Politics/btAFFggl1LoKBNZK0a45fJ/China-not-in-favour-of-proposed-Brics-credit-rating-agency.html.

[xli] Export-Import Bank of India (EXIM Bank), “Research Paper on setting up of a rating agency by BRICS,” June 2016 (unpublished).

[xlii] Ibid

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Preety Bhogal is a PhD candidate in the Department of Economics at Kansas State University. She previously worked at Observer Research Foundation and Centre for ...

Read More +